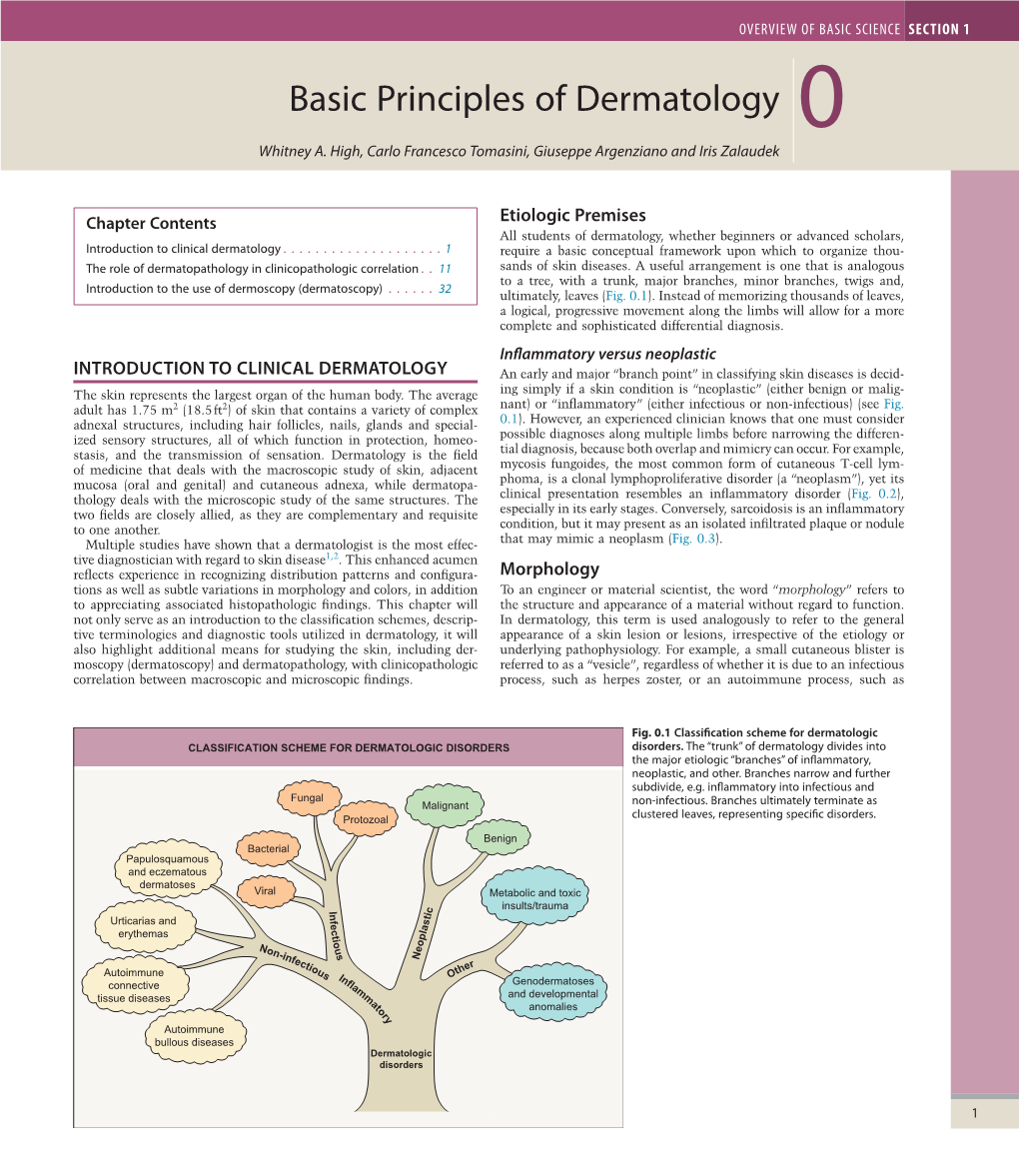

Basic Principles of Dermatology 0 Whitney A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Pathomorpholog.Pdf

Ukrаiniаn Medicаl Stomаtologicаl Аcаdemy THE DEPАRTАMENT OF PАTHOLOGICАL АNАTOMY WITH SECTIONSL COURSE MАNUАL for the foreign students GENERАL PАTHOMORPHOLOGY Poltаvа-2020 УДК:616-091(075.8) ББК:52.5я73 COMPILERS: PROFESSOR I. STАRCHENKO ASSOCIATIVE PROFESSOR O. PRYLUTSKYI АSSISTАNT A. ZADVORNOVA ASSISTANT D. NIKOLENKO Рекомендовано Вченою радою Української медичної стоматологічної академії як навчальний посібник для іноземних студентів – здобувачів вищої освіти ступеня магістра, які навчаються за спеціальністю 221 «Стоматологія» у закладах вищої освіти МОЗ України (протокол №8 від 11.03.2020р) Reviewers Romanuk A. - MD, Professor, Head of the Department of Pathological Anatomy, Sumy State University. Sitnikova V. - MD, Professor of Department of Normal and Pathological Clinical Anatomy Odessa National Medical University. Yeroshenko G. - MD, Professor, Department of Histology, Cytology and Embryology Ukrainian Medical Dental Academy. A teaching manual in English, developed at the Department of Pathological Anatomy with a section course UMSA by Professor Starchenko II, Associative Professor Prylutsky OK, Assistant Zadvornova AP, Assistant Nikolenko DE. The manual presents the content and basic questions of the topic, practical skills in sufficient volume for each class to be mastered by students, algorithms for describing macro- and micropreparations, situational tasks. The formulation of tests, their number and variable level of difficulty, sufficient volume for each topic allows to recommend them as preparation for students to take the licensed integrated exam "STEP-1". 2 Contents p. 1 Introduction to pathomorphology. Subject matter and tasks of 5 pathomorphology. Main stages of development of pathomorphology. Methods of pathanatomical diagnostics. Methods of pathomorphological research. 2 Morphological changes of cells as response to stressor and toxic damage 8 (parenchimatouse / intracellular dystrophies). -

Melanocytes and Their Diseases

Downloaded from http://perspectivesinmedicine.cshlp.org/ on October 2, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Melanocytes and Their Diseases Yuji Yamaguchi1 and Vincent J. Hearing2 1Medical, AbbVie GK, Mita, Tokyo 108-6302, Japan 2Laboratory of Cell Biology, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892 Correspondence: [email protected] Human melanocytes are distributed not only in the epidermis and in hair follicles but also in mucosa, cochlea (ear), iris (eye), and mesencephalon (brain) among other tissues. Melano- cytes, which are derived from the neural crest, are unique in that they produce eu-/pheo- melanin pigments in unique membrane-bound organelles termed melanosomes, which can be divided into four stages depending on their degree of maturation. Pigmentation production is determined by three distinct elements: enzymes involved in melanin synthesis, proteins required for melanosome structure, and proteins required for their trafficking and distribution. Many genes are involved in regulating pigmentation at various levels, and mutations in many of them cause pigmentary disorders, which can be classified into three types: hyperpigmen- tation (including melasma), hypopigmentation (including oculocutaneous albinism [OCA]), and mixed hyper-/hypopigmentation (including dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria). We briefly review vitiligo as a representative of an acquired hypopigmentation disorder. igments that determine human skin colors somes can be divided into four stages depend- Pinclude melanin, hemoglobin (red), hemo- ing on their degree of maturation. Early mela- siderin (brown), carotene (yellow), and bilin nosomes, especially stage I melanosomes, are (yellow). Among those, melanins play key roles similar to lysosomes whereas late melanosomes in determining human skin (and hair) pigmen- contain a structured matrix and highly dense tation. -

Tinea Versicolor Mimicking Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris

Tinea Versicolor Mimicking Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris Capt Matthew J. Darling, MC, USAF; CPT Matthew C. Lambiase, MC, USA; Capt R. John Young, MC, USAF Tinea versicolor is a common noninvasive cuta- neous fungal disease. We recount a case of tinea versicolor that mimicked type I (classic adult) pityriasis rubra pilaris. A 54-year-old white man reported a 20-year history of a recurrent pruritic eruption that had marginally improved with use of selenium sulfide shampoo and treatment with oral antihistamines. Results of a skin examination revealed erythematous plaques; islands of spared skin; and follicular erythematous keratotic papules on the trunk, shoulders, and upper arms. A lesion was scraped to obtain skin scales for potassium hydroxide staining. Examination of the stained samples revealed the characteristic “spaghetti and meatballs,” confirming the diagnosis. Cutis. 2005;75:265-267. Case Report A 54-year-old white man presented with a 20-year history of a recurrent pruritic eruption that had marginally improved with use of selenium sulfide shampoo and oral antihistamine therapy. Erythem- atous scaly plaques were noted over the trunk and extremities (Figure 1). Islands of spared skin were most notable on the trunk (Figure 2). Follicular, erythematous, keratotic papules were noted on the shoulders and upper arms (Figure 3). Results of Wood lamp examination revealed a yellow-green Figure 1. Erythematous scaly plaques and islands of fluorescence of the plaques. Results of potassium spared skin on the chest. hydroxide (KOH) staining revealed numerous yeast and hyphae. The patient was diagnosed with tinea versicolor and treated with itraconazole 200 mg/d for 2 weeks. -

Dermatology Eponyms – Sign –Lexicon (P)

2XU'HUPDWRORJ\2QOLQH Historical Article Dermatology Eponyms – sign –Lexicon (P)� Part 2 Piotr Brzezin´ ski1,2, Masaru Tanaka3, Husein Husein-ElAhmed4, Marco Castori5, Fatou Barro/Traoré6, Satish Kashiram Punshi7, Anca Chiriac8,9 1Department of Dermatology, 6th Military Support Unit, Ustka, Poland, 2Institute of Biology and Environmental Protection, Department of Cosmetology, Pomeranian Academy, Slupsk, Poland, 3Department of Dermatology, Tokyo Women’s Medical University Medical Center East, Tokyo, Japan, 4Department of Dermatology, San Cecilio University Hospital, Granada, Spain, 5Medical Genetics, Department of Experimental Medicine, Sapienza - University of Rome, San Camillo-Forlanini Hospital, Rome, Italy, 6Department of Dermatology-Venerology, Yalgado Ouédraogo Teaching Hospital Center (CHU-YO), Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 7Consultant in Skin Dieseases, VD, Leprosy & Leucoderma, Rajkamal Chowk, Amravati – 444 601, India, 8Department of Dermatology, Nicolina Medical Center, Iasi, Romania, 9Department of Dermato-Physiology, Apollonia University Iasi, Strada Muzicii nr 2, Iasi-700399, Romania Corresponding author: Piotr Brzezin′ski, MD PhD, E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Eponyms are used almost daily in the clinical practice of dermatology. And yet, information about the person behind the eponyms is difficult to find. Indeed, who is? What is this person’s nationality? Is this person alive or dead? How can one find the paper in which this person first described the disease? Eponyms are used to describe not only disease, but also clinical signs, surgical procedures, staining techniques, pharmacological formulations, and even pieces of equipment. In this article we present the symptoms starting with (P) and other. The symptoms and their synonyms, and those who have described this symptom or phenomenon. Key words: Eponyms; Skin diseases; Sign; Phenomenon Port-Light Nose sign or tylosis palmoplantaris is widely related with the onset of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. -

Uniform Faint Reticulate Pigment Network - a Dermoscopic Hallmark of Nevus Depigmentosus

Our Dermatology Online Letter to the Editor UUniformniform ffaintaint rreticulateeticulate ppigmentigment nnetworketwork - A ddermoscopicermoscopic hhallmarkallmark ooff nnevusevus ddepigmentosusepigmentosus Surit Malakar1, Samipa Samir Mukherjee2,3, Subrata Malakar3 11st Year Post graduate, Department of Dermatology, SUM Hospital Bhubaneshwar, India, 2Department of Dermatology, Cloud nine Hospital, Bangalore, India, 3Department of Dermatology, Rita Skin Foundation, Kolkata, India Corresponding author: Dr. Samipa Samir Mukherjee, E-mail: [email protected] Sir, ND is a form of cutaneous mosaicism with functionally defective melanocytes and abnormal melanosomes. Nevus depigmentosus (ND) is a localized Histopathologic examination shows normal to hypopigmentation which most of the time is congenital decreased number of melanocytes with S-100 stain and and not uncommonly a diagnostic challenge. ND lesions less reactivity with 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine reaction are sometimes difficult to differentiate from other and no melanin incontinence [2]. Electron microscopic hypopigmented lesions like vitiligo, ash leaf macules and findings show stubby dendrites of melanocytes nevus anemicus. Among these naevus depigmentosus containing autophagosomes with aggregates of poses maximum difficulty in differentiating from ash melanosomes. leaf macules because of clinical as well as histological similarities [1]. Although the evolution of newer diagnostic For ease of understanding the pigmentary network techniques like dermoscopy has obviated the -

Guide to Policy & Practice Questions

OREGON BOARD OF CHIROPRACTIC EXAMINERS GUIDE TO POLICY & PRACTICE QUESTIONS 530 Center St NE, suite 620 Salem, OR 97301 (503) 378-5816 [email protected] Updated/Adopted: 9/17/2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 DEVICES, PROCEDURES, AND SUBSTANCES ............................................................................................................................... 6 DEVICES ................................................................................................................................................................ 6 BAX 3000 AND SIMILAR DEVICES................................................................................................................................................ 6 BIOPTRON LIGHT THERAPY ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 CPAP MACHINE, ORDERING ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 CTD MARK I MULTI-TORSION TRACTION DEVICE................................................................................................................... 6 DYNATRON 2000 ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Clinicopathological Correlation of Acquired Hyperpigmentary Disorders

Symposium Clinicopathological correlation of acquired Dermatopathology hyperpigmentary disorders Anisha B. Patel, Raj Kubba1, Asha Kubba1 Department of Dermatology, ABSTRACT Oregon Health Sciences University, Portland, Oregon, Acquired pigmentary disorders are group of heterogenous entities that share single, most USA, 1Delhi Dermatology Group, Delhi Dermpath significant, clinical feature, that is, dyspigmentation. Asians and Indians, in particular, are mostly Laboratory, New Delhi, India affected. Although the classic morphologies and common treatment options of these conditions have been reviewed in the global dermatology literature, the value of histpathological evaluation Address for correspondence: has not been thoroughly explored. The importance of accurate diagnosis is emphasized here as Dr. Asha Kubba, the underlying diseases have varying etiologies that need to be addressed in order to effectively 10, Aradhana Enclave, treat the dyspigmentation. In this review, we describe and discuss the utility of histology in the R.K. Puram, Sector‑13, diagnostic work of hyperpigmentary disorders, and how, in many cases, it can lead to targeted New Delhi ‑ 110 066, India. E‑mail: and more effective therapy. We focus on the most common acquired pigmentary disorders [email protected] seen in Indian patients as well as a few uncommon diseases with distinctive histological traits. Facial melanoses, including mimickers of melasma, are thoroughly explored. These diseases include lichen planus pigmentosus, discoid lupus erythematosus, drug‑induced melanoses, hyperpigmentation due to exogenous substances, acanthosis nigricans, and macular amyloidosis. Key words: Facial melanoses, histology of hyperpigmentary disorders and melasma, pigmentary disorders INTRODUCTION focus on the most common acquired hyperpigmentary disorders seen in Indian patients as well as a few Acquired pigmentary disorders are found all over the uncommon diseases with distinctive histological traits. -

Q-Switched Laser-Induced Chrysiasis Treated with Long-Pulsed Laser

THE CUTTING EDGE SECTION EDITOR: GEORGE J. HRUZA, MD; ASSISTANT SECTION EDITORS: DEE ANNA GLASER, MD; ELAINE SIEGFRIED, MD Q-Switched Laser-Induced Chrysiasis Treated With Long-Pulsed Laser Patricia Lee Yun, MD; Kenneth A. Arndt, MD; R. Rox Anderson, MD; Wellman Laboratories of Photomedicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston (Drs Yun and Anderson), Skin Care Physicians of Chestnut Hill, Chestnut Hill, Mass (Dr Arndt) The Cutting Edge: Challenges in Medical and Surgical Therapeutics REPORT OF A CASE on her cheeks and forehead ranging from 2 to 6 mm (Figure 1). The lesions did not enhance on Wood’s light A 70-year-old woman presented for elective treatment of examination, suggesting dermal pigmentation. In some lentigines on her face. This was her first treatment with areas, portions of the original lentigo were still visible in any laser. She was treated with a Q-switched alexan- the center of the blue macule. There was no discolora- drite laser (755 nm, 50 nanoseconds, 3.5 J/cm2, 15 pulses tion of the sclera, nails, or hair. A subtle blue-gray hue of 4-mm spot diameter; Candela, Wayland, Mass), caus- in the patient’s general skin color was noted at the time ing what appeared to be usual purpura immediately fol- of reexamination. lowing laser exposure of 8 tan macules. Several weeks A punch biopsy specimen of a representative area dem- later, blue-black discoloration was present, and was at- onstrated numerous black particles within macrophages tributed to postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, but in the dermis. A diagnosis of Q-switched laser-induced failed to lighten over the next 4 months. -

Hyperkeratotic and Hypertrophic Lichen Nitidus

Volume 23 Number 10 | October 2017 Dermatology Online Journal || Case Presentation 23 (10): 15 Hyperkeratotic and hypertrophic lichen nitidus Jonathan D Ho1,2 MBBS DSc Dip.Dermpath, Ali Al-Haseni1 MD MSC, Michael T Rosenbaum1 MD, Lynne J Goldberg1,2 MD Affiliations:1 Department of Dermatology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 2Section of Dermatopathology, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts Corresponding Author: Ali Al-Haseni MD, 609 Albany Street, Boston MA 02118, Email: [email protected] Abstract interphalangeal joints of the fingers on both hands (Figure 1A). Biopsy demonstrated marked Lichen nitidus typically presents as shiny pin- orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis, and lichen simplex head sized papules on the trunk and extremities, chronicus-like irregular epidermal hyperplasia. A often affecting children and young adults. In this multifocal lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate prototypical form, it rarely presents a diagnostic expanding one or two dermal papillae with overlying challenge being characterized by distinctive clinical parakeratosis, associated focal hypogranulosis, and and histopathologic findings. We describe a rare occasional individually necrotic keratinocytes were variant of lichen nitidus, which we term “hyperkeratotic noted (Figure 2). These findings were diagnostic and hypertrophic lichen nitidus.” of lichen nitidus. Unusually, the histopathologic and clinically correlated epidermal changes were Keywords: lichen nitidus, hyperkeratosis, somewhat exuberant -

ORIGINAL ARTICLE a Clinical and Histopathological Study of Lichenoid Eruption of Skin in Two Tertiary Care Hospitals of Dhaka

ORIGINAL ARTICLE A Clinical and Histopathological study of Lichenoid Eruption of Skin in Two Tertiary Care Hospitals of Dhaka. Khaled A1, Banu SG 2, Kamal M 3, Manzoor J 4, Nasir TA 5 Introduction studies from other countries. Skin diseases manifested by lichenoid eruption, With this background, this present study was is common in our country. Patients usually undertaken to know the clinical and attend the skin disease clinic in advanced stage histopathological pattern of lichenoid eruption, of disease because of improper treatment due to age and sex distribution of the diseases and to difficulties in differentiation of myriads of well assess the clinical diagnostic accuracy by established diseases which present as lichenoid histopathology. eruption. When we call a clinical eruption lichenoid, we Materials and Method usually mean it resembles lichen planus1, the A total of 134 cases were included in this study prototype of this group of disease. The term and these cases were collected from lichenoid used clinically to describe a flat Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University topped, shiny papular eruption resembling 2 (Jan 2003 to Feb 2005) and Apollo Hospitals lichen planus. Histopathologically these Dhaka (Oct 2006 to May 2008), both of these are diseases show lichenoid tissue reaction. The large tertiary care hospitals in Dhaka. Biopsy lichenoid tissue reaction is characterized by specimen from patients of all age group having epidermal basal cell damage that is intimately lichenoid eruption was included in this study. associated with massive infiltration of T cells in 3 Detailed clinical history including age, sex, upper dermis. distribution of lesions, presence of itching, The spectrum of clinical diseases related to exacerbating factors, drug history, family history lichenoid tissue reaction is wider and usually and any systemic manifestation were noted. -

Volume 73 Some Chemicals That Cause Tumours of the Kidney Or Urinary Bladder in Rodents and Some Other Substances

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION INTERNATIONAL AGENCY FOR RESEARCH ON CANCER IARC MONOGRAPHS ON THE EVALUATION OF CARCINOGENIC RISKS TO HUMANS VOLUME 73 SOME CHEMICALS THAT CAUSE TUMOURS OF THE KIDNEY OR URINARY BLADDER IN RODENTS AND SOME OTHER SUBSTANCES 1999 IARC LYON FRANCE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION INTERNATIONAL AGENCY FOR RESEARCH ON CANCER IARC MONOGRAPHS ON THE EVALUATION OF CARCINOGENIC RISKS TO HUMANS Some Chemicals that Cause Tumours of the Kidney or Urinary Bladder in Rodents and Some Other Substances VOLUME 73 This publication represents the views and expert opinions of an IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, which met in Lyon, 13–20 October 1998 1999 IARC MONOGRAPHS In 1969, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) initiated a programme on the evaluation of the carcinogenic risk of chemicals to humans involving the production of critically evaluated monographs on individual chemicals. The programme was subsequently expanded to include evaluations of carcinogenic risks associated with exposures to complex mixtures, life-style factors and biological agents, as well as those in specific occupations. The objective of the programme is to elaborate and publish in the form of monographs critical reviews of data on carcinogenicity for agents to which humans are known to be exposed and on specific exposure situations; to evaluate these data in terms of human risk with the help of international working groups of experts in chemical carcinogenesis and related fields; and to indicate where additional research efforts are needed. The lists of IARC evaluations are regularly updated and are available on Internet: http://www.iarc.fr/. -

Pityriasis Alba Revisited: Perspectives on an Enigmatic Disorder of Childhood

Pediatric ddermatologyermatology Series Editor: Camila K. Janniger, MD Pityriasis Alba Revisited: Perspectives on an Enigmatic Disorder of Childhood Yuri T. Jadotte, MD; Camila K. Janniger, MD Pityriasis alba (PA) is a localized hypopigmented 80 years ago.2 Mainly seen in the pediatric popula- disorder of childhood with many existing clinical tion, it primarily affects the head and neck region, variants. It is more often detected in individuals with the face being the most commonly involved with a darker complexion but may occur in indi- site.1-3 Pityriasis alba is present in individuals with viduals of all skin types. Atopy, xerosis, and min- all skin types, though it is more noticeable in those with eral deficiencies are potential risk factors. Sun a darker complexion.1,3 This condition also is known exposure exacerbates the contrast between nor- as furfuraceous impetigo, erythema streptogenes, mal and lesional skin, making lesions more visible and pityriasis streptogenes.1 The term pityriasis alba and patients more likely to seek medical atten- remains accurate and appropriate given the etiologic tion. Poor cutaneous hydration appears to be a elusiveness of the disorder. common theme for most riskCUTIS factors and may help elucidate the pathogenesis of this disorder. The Epidemiology end result of this mechanism is inappropriate mel- Pityriasis alba primarily affects preadolescent children anosis manifesting as hypopigmentation. It must aged 3 to 16 years,4 with onset typically occurring be differentiated from other disorders of hypopig- between 6 and 12 years of age.5 Most patients are mentation, such as pityriasis versicolor alba, vitiligo, younger than 15 years,3 with up to 90% aged 6 to nevus depigmentosus, and nevus anemicus.