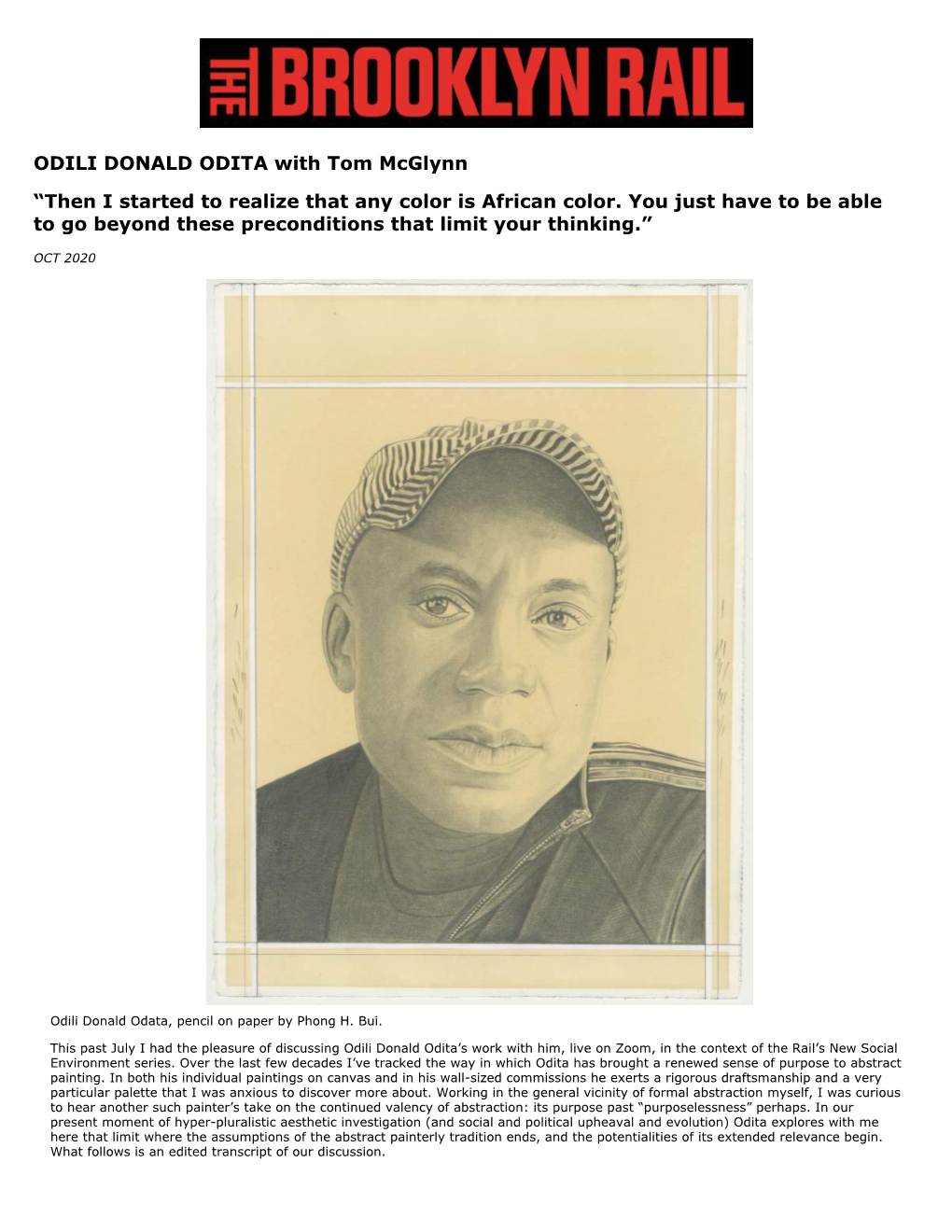

ODILI DONALD ODITA with Tom Mcglynn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri's Detective

MAFIA MOTIFS IN ANDREA CAMILLERI’S DETECTIVE MONTALBANO NOVELS: FROM THE CULTURE AND BREAKDOWN OF OMERTÀ TO MAFIA AS A SCAPEGOAT FOR THE FAILURE OF STATE Adriana Nicole Cerami A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures (Italian). Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Dino S. Cervigni Amy Chambless Roberto Dainotto Federico Luisetti Ennio I. Rao © 2015 Adriana Nicole Cerami ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Adriana Nicole Cerami: Mafia Motifs in Andrea Camilleri’s Detective Montalbano Novels: From the Culture and Breakdown of Omertà to Mafia as a Scapegoat for the Failure of State (Under the direction of Ennio I. Rao) Twenty out of twenty-six of Andrea Camilleri’s detective Montalbano novels feature three motifs related to the mafia. First, although the mafia is not necessarily the main subject of the narratives, mafioso behavior and communication are present in all novels through both mafia and non-mafia-affiliated characters and dialogue. Second, within the narratives there is a distinction between the old and the new generations of the mafia, and a preference for the old mafia ways. Last, the mafia is illustrated as the usual suspect in everyday crime, consequentially diverting attention and accountability away from government authorities. Few critics have focused on Camilleri’s representations of the mafia and their literary significance in mafia and detective fiction. The purpose of the present study is to cast light on these three motifs through a close reading and analysis of the detective Montalbano novels, lending a new twist to the genre of detective fiction. -

Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D) Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2 PHOTOGRAPHY, PROPAGANDA, MONTAGE: Soviet Avant-Garde “We are all primitives of the 20th century” – Ivan Kliun, 1916 UNOVIS members’ aims include the “study of the system of Suprematist projection and the designing of blueprints and plans in accordance with it; ruling off the earth’s expanse into squares, giving each energy cell its place in the overall scheme; organization and accommodation on the earth’s surface of all its intrinsic elements, charting those points and lines out of which the forms of Suprematism will ascend and slip into space.” — Ilya Chashnik , 1921 I. Making “Modern Man” A. Kasimir Malevich – Suprematism 1) Suprematism begins ca. 1913, influenced by Cubo-Futurism 2) Suprematism officially launched, 1915 – manifesto and exhibition titled “0.10 The Last Futurist Exhibition” in Petrograd. B. El (Elazar) Lissitzky 1) “Proun” as utopia 2) Types, and the new modern man C. Modern Woman? 1) Sonia Terk Delaunay in Paris a) “Orphism” or “organic Cubism” 1911 b) “Simultaneous” clothing, ceramics, textiles, cars 1913-20s 2) Natalia Goncharova, “Rayonism” 3) Lyubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova stage designs II. Monuments without Beards -- Vladimir Tatlin A. Constructivism (developed in parallel with Suprematism as sculptural variant) B. Productivism (the tweaking of “l’art pour l’art” to be more socialist) C. Monument to the Third International (Tatlin’s Tower), 1921 III. Collapse of the Avant-Garde? A. 1937 Paris Exposition, 1937 Entartete Kunst, 1939 Popular Front B. -

Henryk Berlewi

HENRYK BERLEWI HENRYK © 2019 Merrill C. Berman Collection © 2019 AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F T HENRYK © O H C E M N 2019 A E R M R R I E L L B . C BERLEWI (1894-1967) HENRYK BERLEWI (1894-1967) Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait,1922. Gouache on paper. Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait, 1946. Pencil on paper. Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Design and production by Jolie Simpson Edited by Dr. Karen Kettering, Independent Scholar, Seattle, USA Copy edited by Lisa Berman Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2019 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2019 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Élément de la Mécano- Facture, 1923. Gouache on paper, 21 1/2 x 17 3/4” (55 x 45 cm) Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the staf of the Frick Collection Library and of the New York Public Library (Art and Architecture Division) for assisting with research for this publication. We would like to thank Sabina Potaczek-Jasionowicz and Julia Gutsch for assisting in editing the titles in Polish, French, and German languages, as well as Gershom Tzipris for transliteration of titles in Yiddish. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Marek Bartelik, author of Early Polish Modern Art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005) and Adrian Sudhalter, Research Curator of the Merrill C. -

The De Stijl Movement in the Netherlands and Related Aspects of Dutch Architecture 1917-1930

25 March 2002 Art History W36456 The De Stijl Movement in the Netherlands and related aspects of Dutch architecture 1917-1930. Walter Gropius, Design for Director’s Office in Weimar Bauhaus, 1923 Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Building, Dessau 1925-26 [Cubism and Architecture: Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Maison Cubiste exhibited at the Salon d’Automne, Paris 1912 Czech Cubism centered around the work of Josef Gocar and Josef Chocol in Prague, notably Gocar’s House of the Black Virgin, Prague and Apt. Building at Prague both of 1913] H.P. (Hendrik Petrus) Berlage Beurs (Stock Exchange), Amsterdam 1897-1903 Diamond Workers Union Building, Amsterdam 1899-1900 J.M. van der Mey, Michel de Klerk and P.L. Kramer’s work on the Sheepvaarthuis, Amsterdam 1911-16. Amsterdam School and in particular the project of social housing at Amsterdam South as well as other isolated housing estates in the expansion of the city. Michel de Klerk (Eigenhaard Development 1914-18; and Piet Kramer (De Dageraad c. 1920) chief proponents of a brick architecture sometimes called Expressionist Robert van t’Hoff, Villa ‘Huis ten Bosch at Huis ter Heide, 1915-16 De Stijl group formed in 1917: Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, Gerritt Rietveld and others (Van der Leck, Huzar, Oud, Jan Wils, Van t’Hoff) De Stijl (magazine) published 1917-31 and edited by Theo van Doesburg Piet Mondrian’s development of “Neo-Plasticism” in Painting Van Doesburg’s Sixteen Points to a Plastic Architecture Projects for exhibition at the Léonce Rosenberg Gallery, Paris 1923 (Villa à Plan transformable in collaboration with Cor van Eestern Gerritt Rietveld Red/Blue Chair c. -

Else Alfelt, Lotti Van Der Gaag, and Defining Cobra

WAS THE MATTER SETTLED? ELSE ALFELT, LOTTI VAN DER GAAG, AND DEFINING COBRA Kari Boroff A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2020 Committee: Katerina Ruedi Ray, Advisor Mille Guldbeck Andrew Hershberger © 2020 Kari Boroff All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katerina Ruedi Ray, Advisor The CoBrA art movement (1948-1951) stands prominently among the few European avant-garde groups formed in the aftermath of World War II. Emphasizing international collaboration, rejecting the past, and embracing spontaneity and intuition, CoBrA artists created artworks expressing fundamental human creativity. Although the group was dominated by men, a small number of women were associated with CoBrA, two of whom continue to be the subject of debate within CoBrA scholarship to this day: the Danish painter Else Alfelt (1910-1974) and the Dutch sculptor Lotti van der Gaag (1923-1999), known as “Lotti.” In contributing to this debate, I address the work and CoBrA membership status of Alfelt and Lotti by comparing their artworks to CoBrA’s two main manifestoes, texts that together provide the clearest definition of the group’s overall ideas and theories. Alfelt, while recognized as a full CoBrA member, created structured, geometric paintings, influenced by German Expressionism and traditional Japanese art; I thus argue that her work does not fit the group’s formal aesthetic or philosophy. Conversely Lotti, who was never asked to join CoBrA, and was rejected from exhibiting with the group, produced sculptures with rough, intuitive, and childlike forms that clearly do fit CoBrA’s ideas as presented in its two manifestoes. -

Contemporary Art Magazine Issue # Sixteen December | January Twothousandnine Spedizione in A.P

contemporary art magazine issue # sixteen december | january twothousandnine Spedizione in a.p. -70% _ DCB Milano NOVEMBER TO JANUARY, 2009 KAREN KILIMNIK NOVEMBER TO JANUARY, 2009 WadeGUYTON BLURRY CatherineSULLIVAN in collaboration with Sean Griffin, Dylan Skybrook and Kunle Afolayan Triangle of Need VibekeTANDBERG The hamburger turns in my stomach and I throw up on you. RENOIR Liquid hamburger. Then I hit you. After that we are both out of words. January - February 2009 DEBUSSY URS FISCHER GALERIE EVA PRESENHUBER WWW.PRESENHUBER.COM TEL: +41 (0) 43 444 70 50 / FAX: +41 (0) 43 444 70 60 LIMMATSTRASSE 270, P.O.BOX 1517, CH–8031 ZURICH GALLERY HOURS: TUE-FR 12-6, SA 11-5 DOUG AITKEN, EMMANUELLE ANTILLE, MONIKA BAER, MARTIN BOYCE, ANGELA BULLOCH, VALENTIN CARRON, VERNE DAWSON, TRISHA DONNELLY, MARIA EICHHORN, URS FISCHER, PETER FISCHLI/DAVID WEISS, SYLVIE FLEURY, LIAM GILLICK, DOUGLAS GORDON, MARK HANDFORTH, CANDIDA HÖFER, KAREN KILIMNIK, ANDREW LORD, HUGO MARKL, RICHARD PRINCE, GERWALD ROCKENSCHAUB, TIM ROLLINS AND K.O.S., UGO RONDINONE, DIETER ROTH, EVA ROTHSCHILD, JEAN-FRÉDÉRIC SCHNYDER, STEVEN SHEARER, JOSH SMITH, BEAT STREULI, FRANZ WEST, SUE WILLIAMS DOUBLESTANDARDS.NET 1012_MOUSSE_AD_Dec2008.indd 1 28.11.2008 16:55:12 Uhr Galleria Emi Fontana MICHAEL SMITH Viale Bligny 42 20136 Milano Opening 17 January 2009 T. +39 0258322237 18 January - 28 February F. +39 0258306855 [email protected] www.galleriaemifontana.com Photo General Idea, 1981 David Lamelas, The Violent Tapes of 1975, 1975 - courtesy: Galerie Kienzie & GmpH, Berlin L’allarme è generale. Iper e sovraproduzione, scialo e vacche grasse si sono tra- sformati di colpo in inflazione, deflazione e stagflazione. -

Extended Sensibilities Homosexual Presence in Contemporary Art

CHARLEY BROWN SCOTT BURTON CRAIG CARVER ARCH CONNELLY JANET COOLING BETSY DAMON NANCY FRIED EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART JEDD GARET GILBERT & GEORGE LEE GORDON HARMONY HAMMOND JOHN HENNINGER JERRY JANOSCO LILI LAKICH LES PETITES BONBONS ROSS PAXTON JODY PINTO CARLA TARDI THE NEW MUSEUM FRAN WINANT EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART CHARLEY BROWN HARMONY HAMMOND SCOTT BURTON JOHN HENNINGER CRAIG CARVER JERRY JANOSCO ARCH CONNELLY LILI LAKICH JANET COOLING LES PETITES BONBONS BETSY DAMON ROSS PAXTON NANCY FRIED JODY PINTO JEDD GARET CARLA TARDI GILBERT & GEORGE FRAN WINANT LE.E GORDON Daniel J. Cameron Guest Curator The New Museum EXTENDED SENSIBILITIES STAFF ACTIVITIES COUNCJT . Robin Dodds Isabel Berley HOMOSEXUAL PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART Nina Garfinkel Marilyn Butler N Lynn Gumpert Arlene Doft ::;·z17 John Jacobs Elliot Leonard October 16-December 30, 1982 Bonnie Johnson Lola Goldring .H6 Ed Jones Nanette Laitman C:35 Dieter Morris Kearse Dorothy Sahn Maria Reidelbach Laura Skoler Rosemary Ricchio Jock Truman Ned Rifkin Charles A. Schwefel INTERNS Maureen Stewart Konrad Kaletsch Marcia Thcker Thorn Middlebrook GALLERY ATTENDANTS VOLUNTEERS Joanne Brockley Connie Bangs Anne Glusker Bill Black Marcia Landsman Carl Blumberg Sam Robinson Jeanne Breitbart Jennifer Q. Smith Mary Campbell Melissa Wolf Marvin Coats Jody Cremin This exhibition is supported by a grant from the National Endowment for BOARD OF TRUSTEES Joanna Dawe the Arts in Washington, D.C., a Federal Agency, and is made possible in Jack Boulton Mensa Dente part by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts. Elaine Dannheisser Gary Gale Library of Congress Catalog Number: 82-61279 John Fitting, Jr. -

The Third in a Three Part Series on Art Not Only How to Explain Modern Art (But How to Have Your Students Create Their Own Abstract Project)

The Third in a Three Part Series on Art Not Only How to Explain Modern Art (But How to Have Your Students Create Their Own Abstract Project) Michael Hoctor Keywords: Paul Gauguin Mark Rothko Pablo Picasso Jackson Pollock Synchromy Peggy Guggenheim Armory Show Collage Abstract expressionism Color Field Painting Action Painting MODERN ABSTRACT ART Part Three This article will conclude with a class lesson to help students appreciate and better understand art without narrative. The class will produce a 20th-Century Abstract Art Project, with an optional step into 21st Century Digital Art. REALISM ABSTRACTION DIVIDE This article skips a small rock across a large body of well-documented art history, including 650,000 books covering fine art that are currently available, as well as approximately 55,000 on critical insights, and almost 15,000 books examining the methods of individual artists and how they approached their work. You, of course can read a lot of them in your spare time! But today, our goal is to is gain a better understanding of why, at the very beginning of the 20th century, there was a major departure in how some groups of "avant-garde" painters approached their canvas, abandoning realistic art. The rock's trajectory attempts to show how the camera's extraordinary technology provoked some phenomenal artists to re- examine how they painted, inventing new methods of applying colors in a far less photographic manner that was far more subjective, departing from: what we see to focus on what way we see. 2 These innovators produced art that in time became incredibly valued. -

Gce History of Art Major Modern Art Movements

FACTFILE: GCE HISTORY OF ART MAJOR MODERN ART MOVEMENTS Major Modern Art Movements Key words Overview New types of art; collage, assemblage, kinetic, The range of Major Modern Art Movements is photography, land art, earthworks, performance art. extensive. There are over 100 known art movements and information on a selected range of the better Use of new materials; found objects, ephemeral known art movements in modern times is provided materials, junk, readymades and everyday items. below. The influence of one art movement upon Expressive use of colour particularly in; another can be seen in the definitions as twentieth Impressionism, Post Impressionism, Fauvism, century art which became known as a time of ‘isms’. Cubism, Expressionism, and colour field painting. New Techniques; Pointilism, automatic drawing, frottage, action painting, Pop Art, Neo-Impressionism, Synthesism, Kinetic Art, Neo-Dada and Op Art. 1 FACTFILE: GCE HISTORY OF ART / MAJOR MODERN ART MOVEMENTS The Making of Modern Art The Nine most influential Art Movements to impact Cubism (fl. 1908–14) on Modern Art; Primarily practised in painting and originating (1) Impressionism; in Paris c.1907, Cubism saw artists employing (2) Fauvism; an analytic vision based on fragmentation and multiple viewpoints. It was like a deconstructing of (3) Cubism; the subject and came as a rejection of Renaissance- (4) Futurism; inspired linear perspective and rounded volumes. The two main artists practising Cubism were Pablo (5) Expressionism; Picasso and Georges Braque, in two variants (6) Dada; ‘Analytical Cubism’ and ‘Synthetic Cubism’. This movement was to influence abstract art for the (7) Surrealism; next 50 years with the emergence of the flat (8) Abstract Expressionism; picture plane and an alternative to conventional perspective. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Lesson Helen Frankenthaler/Color Field Paintings 6 Kimball Art Center & Park City Ed

LESSON 6 Helen Frankenthaler Color Field Paintings Verbal Directions LESSON HELEN FRANKENTHALER/COLOR FIELD PAINTINGS 6 KIMBALL ART CENTER & PARK CITY ED. FOUNDATION LESSON OVERVIEW SUPPLIES • Images of Frankenthaller’s Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) was an experimental abstract artwork. expressionist painter, who described her paintings as being • Samples of Color Field improvisations based on real or imaginary ideas of nature. Students Paintings. will work with watercolors and movement to create color fields while • Butcher paper/Tarps/Trays. enriching their understanding of the properties of color in painting. • Scrap paper for Experiments. • White Wax Crayons. INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES • Watercolor Paper. • Paper Towel/Sponges . • Learn about Helen Frankenthaler. • Liquid watercolors. • Learn about abstraction and the properties of color. • Cups or Palettes • Learn about action painting and the painting process. • Pipettes or Straws. • Create a painting inspired by Helen Frankenthaller’s abstract paintings. HELEN FRANKENTHALLER Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) has long been recognized as one of the great American artists of the twentieth century. She was well known among the second generation of postwar American abstract painters and is widely credited for playing a pivotal role in the transition from Abstract Expressionism to Color Field painting. Through her invention of the soak-stain technique, she expanded the possibilities of abstract painting, while at times referencing figuration and landscape in unique ways. She produced a body of work whose impact on contemporary art has been profound and continues to grow. LESSON HELEN FRANKENTHALER/COLOR FIELD PAINTINGS 6 KIMBALL ART CENTER & PARK CITY ED. FOUNDATION LESSON PLAN 1. Introduce students to the work and life of Helen Frankenthaler.