The Race to Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Launcher Moves to Vehicle Assembly Building EGS MONTHLY HIGHLIGHTS

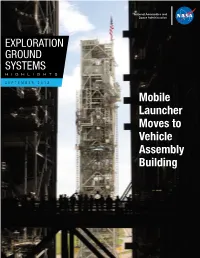

National Aeronautics and Space Administration EXPLORATION GROUND SYSTEMS HIGHLIGHTS SEPTEMBER 2018 Mobile Launcher Moves to Vehicle Assembly Building EGS MONTHLY HIGHLIGHTS 3 Mobile launcher on the move 4 In the driver’s seat 5 Prepping for Underway Recovery Test 7 6 Employees, guests view ML move MOBILE LAUNCHER ON THE MOVE NASA’s mobile launcher is inside High Bay 3 at the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) on Sept. 11, 2018, at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Photo credit: NASA/Frank Michaux NASA’s mobile launcher, atop crawler-transporter 2, traveled from Launch Pad 39B to the Vehicle Assembly Building at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, on Sept. 7, 2018. Arriving late in the afternoon, the mobile launcher stopped at the entrance to the VAB. Early the next day, Sept. 8, engineers and technicians rotated and extended the crew access arm near the top of the mobile launcher tower. Then the mobile launcher was moved inside High Bay 3, where it will spend about seven months undergoing verification and validation testing with the 10 levels of new work platforms, ensuring that it can provide support to the agency’s Space Launch System (SLS). The 380-foot-tall structure is equipped with the crew access Cliff Lanham, NASA project manager for the mobile launcher, takes a break arm and several umbilicals that will provide power, environmental to attend the employee event for the mobile launcher move to the Vehicle control, pneumatics, communication and electrical connections Assembly Building on Sept. 7, 2018, at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. -

NASA Space Life and Physical Sciences and Research Applications

NASA Space Life and Physical Sciences and Research Applications SLSPRA has 11 topics listed below and on the following pages for your consideration and possible involvement. (1) Program: Physical Sciences Program (2) Research Title: Dusty Plasmas (3) Research Overview: Dusty plasma research uses dusty plasmas – mixtures of electrons, ions, and charged micron-size particles as a model system to understand astronomical phenomena involving dust-laden plasmas, and as a simplified system modelling the behavior of many-body systems in problems of statistical and condensed matter physics. Dusty plasma research also addresses practical questions of dust management in planetary exploration missions. Proposals are sought for research on dusty plasmas, particularly on the transport of particles in dusty plasmas. 4) NASA Contact a. Name: Bradley Carpenter, Ph.D. b. Organization: NASA Headquarters Space Life and Physical Sciences Research and Applications (SLPSRA) c. Work Phone: (202) 358-0826 d. Email: [email protected] 5) Commercial Entity: a. Company Name: na b. Contact Name: na c. Work Phone: na d. Cell Phone: na e Email: na 6) Partner contribution No NASA Partner contributions 7) Intellectual property management: No NASA Partner intellectual property concerns 8) Additional Information: All publications that result from an awarded EPSCOR study shall acknowledge NASA Space Life and Physical Sciences Research and Applications (SLPSRA). NNH20ZHA001C NASA EPSCoR Rapid Response Research (R3) NASA Space Life and Physical Sciences and Research Applications (continued) 1) Program: Fluids Physics and Combustion Science 2) Research Title: Drop Tower Studies 3) Research Overview: Fundamental discoveries made by NASA researchers over the last 50 years in fluids physics and combustion have helped enable advances in fluids management on spacecraft water recovery and thermal management systems, spacecraft fire safety, and fundamental combustion and fluids physics including low-temperature hydrocarbon oxidation, soot formation and flame stability. -

E&T Magazine, Volume 11, Issue 9, October 2016

88 TIME OUT COLUMNIST One of the great joys of inventing something is being able to name it – unless of course no one is meant to know about it. That’s how Léon Theremin ended up the proud inventor of a device called ‘The Thing’. by Justin Pollard SPY EQUIPMENT Competition himself listening in to his American colleagues on an open FEAR AT THE HEART What is The Thing thinking? channel. It was just by luck that The wittiest caption emailed he happened to be listening on OF POWER: THEREMIN to [email protected] the right frequency when the by 5 October 2016 wins a Soviets were ‘painting’ the Thing AND THE THING pair of books from Haynes. with its radio signal. The Americans were informed and in March 1951 the official residence. What he didn’t device was discovered inside the know was that, from that Great Seal. The device was moment, it was transmitting his quickly copied by the British conversations back to the NKVD. and Americans and rapidly Now, the Americans weren’t installed wherever they might idiots. They were aware that get away with it. unprompted gifts from Soviet The idea of a passive institutions might contain more electronic transmitting device than they bargained for and they has since taken on a life of its expected attempts to be made to own – we just don’t call them bug the ambassador’s residence ‘Things’, we call them RFIDs. So in Moscow. Gifts were checked to next time you’re making a make sure they weren’t contactless payment, or using an ‘transmitting’ and the rooms Oystercard, it’s worth were regularly swept for bugs. -

Race to Space Educator Edition

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Grade Level RACE TO SPACE 10-11 Key Topic Instructional Objectives U.S. space efforts from Students will 1957 - 1969 • analyze primary and secondary source documents to be used as Degree of Difficulty supporting evidence; Moderate • incorporate outside information (information learned in the study of the course) as additional support; and Teacher Prep Time • write a well-developed argument that answers the document-based 2 hours essay question regarding the analogy between the Race to Space and the Cold War. Problem Duration 60 minutes: Degree of Difficulty -15 minute document analysis For the average AP US History student the problem may be at a moderate - 45 minute essay writing difficulty level. -------------------------------- Background AP Course Topics This problem is part of a series of Social Studies problems celebrating the - The United States and contributions of NASA’s Apollo Program. the Early Cold War - The 1950’s On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy spoke before a special joint - The Turbulent 1960’s session of Congress and challenged the country to safely send and return an American to the Moon before the end of the decade. President NCSS Social Studies Kennedy’s vision for the three-year old National Aeronautics and Space Standards Administration (NASA) motivated the United States to develop enormous - Time, Continuity technological capabilities and inspired the nation to reach new heights. and Change Eight years after Kennedy’s speech, NASA’s Apollo program successfully - People, Places and met the president’s challenge. On July 20, 1969, the world witnessed one of Environments the most astounding technological achievements in the 20th century. -

The Space Race

The Space Race Aims: To arrange the key events of the “Space Race” in chronological order. To decide which country won the Space Race. Space – the Final Frontier “Space” is everything Atmosphere that exists outside of our planet’s atmosphere. The atmosphere is the layer of Earth gas which surrounds our planet. Without it, none of us would be able to breathe! Space The sun is a star which is orbited (circled) by a system of planets. Earth is the third planet from the sun. There are nine planets in our solar system. How many of the other eight can you name? Neptune Saturn Mars Venus SUN Pluto Uranus Jupiter EARTH Mercury What has this got to do with the COLD WAR? Another element of the Cold War was the race to control the final frontier – outer space! Why do you think this would be so important? The Space Race was considered important because it showed the world which country had the best science, technology, and economic system. It would prove which country was the greatest of the superpowers, the USSR or the USA, and which political system was the best – communism or capitalism. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xvaEvCNZymo The Space Race – key events Discuss the following slides in your groups. For each slide, try to agree on: • which of the three options is correct • whether this was an achievement of the Soviet Union (USSR) or the Americans (USA). When did humans first send a satellite into orbit around the Earth? 1940s, 1950s or 1960s? Sputnik 1 was launched in October 1957. -

Mars, the Nearest Habitable World – a Comprehensive Program for Future Mars Exploration

Mars, the Nearest Habitable World – A Comprehensive Program for Future Mars Exploration Report by the NASA Mars Architecture Strategy Working Group (MASWG) November 2020 Front Cover: Artist Concepts Top (Artist concepts, left to right): Early Mars1; Molecules in Space2; Astronaut and Rover on Mars1; Exo-Planet System1. Bottom: Pillinger Point, Endeavour Crater, as imaged by the Opportunity rover1. Credits: 1NASA; 2Discovery Magazine Citation: Mars Architecture Strategy Working Group (MASWG), Jakosky, B. M., et al. (2020). Mars, the Nearest Habitable World—A Comprehensive Program for Future Mars Exploration. MASWG Members • Bruce Jakosky, University of Colorado (chair) • Richard Zurek, Mars Program Office, JPL (co-chair) • Shane Byrne, University of Arizona • Wendy Calvin, University of Nevada, Reno • Shannon Curry, University of California, Berkeley • Bethany Ehlmann, California Institute of Technology • Jennifer Eigenbrode, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center • Tori Hoehler, NASA/Ames Research Center • Briony Horgan, Purdue University • Scott Hubbard, Stanford University • Tom McCollom, University of Colorado • John Mustard, Brown University • Nathaniel Putzig, Planetary Science Institute • Michelle Rucker, NASA/JSC • Michael Wolff, Space Science Institute • Robin Wordsworth, Harvard University Ex Officio • Michael Meyer, NASA Headquarters ii Mars, the Nearest Habitable World October 2020 MASWG Table of Contents Mars, the Nearest Habitable World – A Comprehensive Program for Future Mars Exploration Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... -

Chapter Fourteen Men Into Space: the Space Race and Entertainment Television Margaret A. Weitekamp

CHAPTER FOURTEEN MEN INTO SPACE: THE SPACE RACE AND ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISION MARGARET A. WEITEKAMP The origins of the Cold War space race were not only political and technological, but also cultural.1 On American television, the drama, Men into Space (CBS, 1959-60), illustrated one way that entertainment television shaped the United States’ entry into the Cold War space race in the 1950s. By examining the program’s relationship to previous space operas and spaceflight advocacy, a close reading of the 38 episodes reveals how gender roles, the dangers of spaceflight, and the realities of the Moon as a place were depicted. By doing so, this article seeks to build upon and develop the recent scholarly investigations into cultural aspects of the Cold War. The space age began with the launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957. But the space race that followed was not a foregone conclusion. When examining the United States, scholars have examined all of the factors that led to the space technology competition that emerged.2 Notably, Howard McCurdy has argued in Space and the American Imagination (1997) that proponents of human spaceflight 1 Notably, Asif A. Siddiqi, The Rocket’s Red Glare: Spaceflight and the Soviet Imagination, 1857-1957, Cambridge Centennial of Flight (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010) offers the first history of the social and cultural contexts of Soviet science and the military rocket program. Alexander C. T. Geppert, ed., Imagining Outer Space: European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) resulted from a conference examining the intersections of the social, cultural, and political histories of spaceflight in the Western European context. -

Fifty Years Ago This May, John F. Kennedy Molded Cold War Fears Into a Collective Resolve to Achieve the Almost Unthinkable: Land American Astronauts on the Moon

SHOOTING FOR THE MOON Fifty years ago this May, John F. Kennedy molded Cold War fears into a collective resolve to achieve the almost unthinkable: land American astronauts on the moon. In a new book, Professor Emeritus John Logsdon mines the details behind the president’s epochal decision. .ORG S GE A IM NASA Y OF S NASA/COURTE SHOOTING FOR THE MOON Fifty years ago this May, John F. Kennedy molded Cold War fears into a collective resolve to achieve the almost unthinkable: land American astronauts on the moon. In a new book, Professor Emeritus John Logsdon mines the details behind the president’s epochal decision. BY JOHN M. LOGSDON President John F. Kennedy, addressing a joint session of Congress on May 25, 1961, had called for “a great new American enterprise.” n the middle of a July night in 1969, standing The rest, of course, is history: The Eagle landed. Before a TV outside a faceless building along Florida’s eastern audience of half a billion people, Neil Armstrong took “one giant coast, three men in bright white spacesuits strolled leap for mankind,” and Buzz Aldrin emerged soon after, describing by, a few feet from me—on their way to the moon. the moonscape before him as “magnificent desolation.” They climbed into their spacecraft, atop a But the landing at Tranquility Base was not the whole story massive Saturn V rocket, and, a few hours later, of Project Apollo. I with a powerful blast, went roaring into space, the It was the story behind the story that had placed me at weight on their shoulders far more than could be measured Kennedy Space Center that July day. -

![PAVEL MIKHAILOVICH VOROBIEV May 29, 1998 Interviewers: Mark Davison, Rebecca Wright, Paul Rollins, [Interview Conducted with Interpreter from TTI]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0389/pavel-mikhailovich-vorobiev-may-29-1998-interviewers-mark-davison-rebecca-wright-paul-rollins-interview-conducted-with-interpreter-from-tti-640389.webp)

PAVEL MIKHAILOVICH VOROBIEV May 29, 1998 Interviewers: Mark Davison, Rebecca Wright, Paul Rollins, [Interview Conducted with Interpreter from TTI]

The oral histories placed on this Website are from a few of the many people who worked together to meet the challenges of the Shuttle-Mir Program. The words that you will read are the transcripts from the audio-recorded, personal interviews conducted with each of these individuals. In order to preserve the integrity of their audio record, these histories are presented with limited revisions and reflect the candid conversational style of the oral history format. Brackets or an ellipsis mark will indicate if the text has been annotated or edited to provide the reader a better understanding of the content. Enjoy “hearing” these factual accountings from these people who were among those who were involved in the day-to-day activities of this historic partnership between the United States and Russia. To continue to the Oral History, choose the link below. Go to Oral History PAVEL MIKHAILOVICH VOROBIEV May 29, 1998 Interviewers: Mark Davison, Rebecca Wright, Paul Rollins, [Interview conducted with interpreter from TTI] Davison: Good afternoon. Today is May 29 [1998], and we're interviewing Mr. Pavel Vorobiev, who works in the Cargo and Manifest Scheduling Working Group. Good afternoon. I'm Mark Davison. We met once before in Russia. I don't know if you remember. This is Paul Rollins and Rebecca Wright helping on the audiovisual. Vorobiev: Very nice to meet you. Davison: Nice to see you again, too. Can you tell us about your educational background in Russia, or a little bit about yourself, where you were born, where you grew up? Vorobiev: I am a native of Moscow. -

THE SOVIET MOON PROGRAM in the 1960S, the United States Was Not the Only Country That Was Trying to Land Someone on the Moon and Bring Him Back to Earth Safely

AIAA AEROSPACE M ICRO-LESSON Easily digestible Aerospace Principles revealed for K-12 Students and Educators. These lessons will be sent on a bi-weekly basis and allow grade-level focused learning. - AIAA STEM K-12 Committee. THE SOVIET MOON PROGRAM In the 1960s, the United States was not the only country that was trying to land someone on the Moon and bring him back to Earth safely. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, also called the Soviet Union, also had a manned lunar program. This lesson describes some of it. Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS): ● Discipline: Engineering Design ● Crosscutting Concept: Systems and System Models ● Science & Engineering Practice: Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions GRADES K-2 K-2-ETS1-1. Ask questions, make observations, and gather information about a situation people want to change to define a simple problem that can be solved through the development of a new or improved object or tool. Have you ever been busy doing something when somebody challenges you to a race? If you decide to join the race—and it is usually up to you whether you join or not—you have to stop what you’re doing, get up, and start racing. By the time you’ve gotten started, the other person is often halfway to the goal. This is the sort of situation the Soviet Union found itself in when President Kennedy in 1961 announced that the United States would set a goal of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth before the end of the decade. -

Features of Legal Support of Space Activities in Ukraine

Features of Legal Support of Space Activities in Ukraine Dmytro Zhuravlov1 Doctor of Law, Professor. First Deputy Director of the Institute of Law and Postgraduate Education of the Ministry of Justice of Ukraine (Kyiv, Ukraine) E-mail: [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2045-9631 Andrii Halunko2 Ph. D. in Law. Inspector of the public order department of the DPA HNPU in Kherson region (Kherson, Ukraine) E-mail: [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1842-2506 In the article, the authors reveal the historical and legal aspects of space activities in Ukraine. The historical and legal acts of the Ukrainian SSR and the Soviet Union, regulating the space industry, are analyzed. Considerable attention was paid to the peculiarities of legal regulation of the activities of the main space design bureaus of the time. It is concluded that the space activities of the USSR — in general and the Ukrainian SSR were provided on the basis of sublegislative normative legal acts (resolutions of the Council of Ministers and orders of the Central bodies of the Communist party). However, the lack of the national space law was offset by systematic and full funding of space activities, resulting in the Soviet Union having a powerful space industry. In the conditions of modern development, Ukraine has all the opportunities to achieve significant development of the space industry, using the positive experience of the USSR and opening access to space activities of private investment. Keywords: space activities, law, space law, space technologies, private investments, Soviet regime, launch vehicles Received: September 11, 2019; accepted: October 07, 2019 Advanced Space Law, Volume 4, 2019: 116-124. -

Russia Celebrates Gagarin's Conquest of Space 12 April 2011, by Stuart Williams

Russia celebrates Gagarin's conquest of space 12 April 2011, by Stuart Williams granted the 27-year-old carpenter's son historical immortality, Gagarin ejected from his capsule and parachuted down into a field in the Saratov region of central Russia. From that moment on, his life, and the course of modern space exploration, would never be the same again. "I believe it was a truly revolutionary event," Medvedev said in an interview with Chinese television, a transcript of which was published by the Kremlin. "It was an outstanding achievement of Soviet space exploration, which divided the world into the time Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin salutes the crowd during before and the time after the flight, which became an official visit to London in 1961. Russia has marked a the space era," Medvedev said. half century since Gagarin became the first man in space, the greatest victory of Soviet science which The Soviet Union scored its greatest propaganda expanded human horizons and still remembered by victory over the United States, spurring its Cold Russians as their finest hour. War foe to eventually retake the lead in the space race by putting men on the moon in 1969. Russia's modern day rulers are using the Russia on Tuesday marked a half century since anniversary to remind Russians of its past Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space, the achievements and Medvedev was later to visit greatest victory of Soviet science which expanded mission control outside Moscow and talk with human horizons and still remembered by Russians modern astronauts on the International Space as their finest hour.