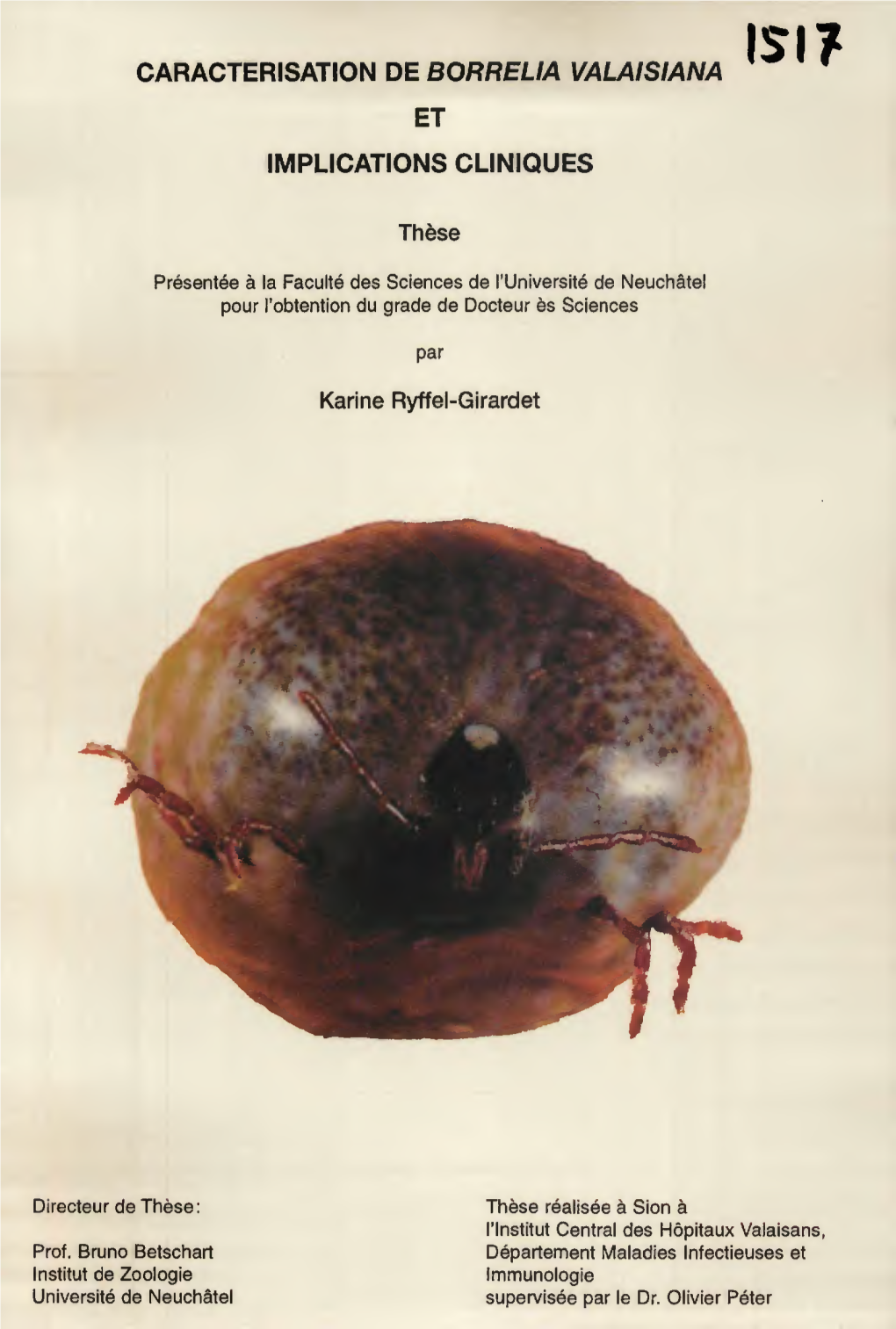

Caracterisation De Borrelia Valaisiana Et Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REVIEW ARTICLES AAEM Ann Agric Environ Med 2005, 12, 165–172

REVIEW ARTICLES AAEM Ann Agric Environ Med 2005, 12, 165–172 ASSOCIATION OF GENETIC VARIABILITY WITHIN THE BORRELIA BURGDORFERI SENSU LATO WITH THE ECOLOGY, EPIDEMIOLOGY OF LYME BORRELIOSIS IN EUROPE 1, 2 1 Markéta Derdáková 'DQLHOD/HQþiNRYi 1Parasitological Institute, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Košice, Slovakia 2Institute of Zoology, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Bratislava, Slovakia 'HUGiNRYi 0 /HQþiNRYi ' $VVRFLDWLRQ RI JHQHWLF YDULDELOLW\ ZLWKLQ WKH Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato with the ecology, epidemiology of Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Ann Agric Environ Med 2005, 12, 165–172. Abstract: Lyme borreliosis (LB) represents the most common vector-borne zoonotic disease in the Northern Hemisphere. The infection is caused by the spirochetes of the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (s.l.) complex which circulate between tick vectors and vertebrate reservoir hosts. The complex of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. encompasses at least 12 species. Genetic variability within and between each species has a considerable impact on pathogenicity, clinical picture, diagnostic methods, transmission mechanisms and its ecology. The distribution of distinct genospecies varies with the different geographic area and over a time. In recent years, new molecular assays have been developed for direct detection and classification of different Borrelia strains. Profound studies of strain heterogeneity initiated a new approach to vaccine development and routine diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Although great progress has been made in characterization of the organism, the present knowledge of ecology and epidemiology of B. burgdorferi s.l. is still incomplete. Further information on the distribution of different Borrelia species and subspecies in their natural reservoir hosts and vectors is needed. Address for correspondence: MVDr. -

Multilocus Sequence Typing Von Borrelia Burgdorferi Sensu Stricto

Multilocus Sequence Typing von Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto und Borrelia afzelii Stämmen aus Europa und den USA: Populationsstruktur, Pathogenität und Patientensymptomatik Sabrina Jungnick München 2018 Aus dem Nationalen Referenzzentrum für Borrelien am Bayrischen Landesamt für Gesundheit und Lebensmittelsicherheit in Oberschleißheim Präsident: Dr. med. Andreas Zapf Multilocus Sequence Typing von Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto und Borrelia afzelii Stämmen aus Europa und den USA: Populationsstruktur, Pathogenität und Patientensymptomatik Dissertation zum Erwerb des Doktorgrades der Medizin an der Medizinischen Fakultät der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität zu München vorgelegt von Sabrina Jungnick aus Ansbach 2018 Mit Genehmigung der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität München Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. med. Dr. phil. Andreas Sing Mitberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Sebastian Suerbaum Prof. Dr. Michael Hoelscher Prof. Dr. Hans – Walter Pfister Mitbetreuung durch den promovierten Mitarbeiter: Dr. med. Volker Fingerle Dekan: Prof. Dr. med. dent. Reinhard Hickel Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 26.04.2018 Teile dieser Arbeit wurden in folgenden Originalartikeln veröffentlicht: 1. Jungnick S, Margos G, Rieger M, Dzaferovic E, Bent SJ, Overzier E, Silaghi C, Walder G, Wex F, Koloczek J, Sing A und Fingerle V. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto and Borrelia afzelii: Population structure and differential pathogenicity. International Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2015. 2. Wang G, Liveris D, Mukherjee P, Jungnick S, Margos G und Schwartz I. Molecular Typing of Borrelia burgdorferi. Current protocols in microbiology. 2014:12C. 5.1-C. 5.31. 3. Castillo-Ramírez S, Fingerle V. Jungnick S, Straubinger RK, Krebs S, Blum H, Meinel DM, Hofmann H, Guertler P, Sing A und Margos G. Trans-Atlantic exchanges have shaped the population structure of the Lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto. -

MOTILITY and CHEMOTAXIS in the LYME DISEASE SPIROCHETE BORRELIA BURGDORFERI: ROLE in PATHOGENESIS by Ki Hwan Moon July, 2016

MOTILITY AND CHEMOTAXIS IN THE LYME DISEASE SPIROCHETE BORRELIA BURGDORFERI: ROLE IN PATHOGENESIS By Ki Hwan Moon July, 2016 Director of Dissertation: MD A. MOTALEB, Ph.D. Major Department: Department of Microbiology and Immunology Abstract Lyme disease is the most prevalent vector-borne disease in United States and is caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. The disease is transmitted from an infected Ixodes scapularis tick to a mammalian host. B. burgdorferi is a highly motile organism and motility is provided by flagella that are enclosed by the outer membrane and thus are called periplasmic flagella. Chemotaxis, the cellular movement in response to a chemical gradient in external environments, empowers bacteria to approach and remain in beneficial environments or escape from noxious ones by modulating their swimming behaviors. Both motility and chemotaxis are reported to be crucial for migration of B. burgdorferi from the tick to the mammalian host, and persistent infection of mice. However, the knowledge of how the spirochete achieves complex swimming is limited. Moreover, the roles of most of the B. burgdorferi putative chemotaxis proteins are still elusive. B. burgdorferi contains multiple copies of chemotaxis genes (two cheA, three cheW, three cheY, two cheB, two cheR, cheX, and cheD), which make its chemotaxis system more complex than other chemotactic bacteria. In the first project of this dissertation, we determined the role of a putative chemotaxis gene cheD. Our experimental evidence indicates that CheD enhances chemotaxis CheX phosphatase activity, and modulated its infectivity in the mammalian hosts. Although CheD is important for infection in mice, it is not required for acquisition or transmission of spirochetes during mouse-tick-mouse infection cycle experiments. -

Master of Environment

Knowledge and Perception of Lyme Disease in Manitoba: Implications for Risk Assessment by Kathleen Crang A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ENVIRONMENT Department of Environment and Geography University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright @ 2009 by Kathleen Crang THB UNIVBRSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADT]ATE STUDIBS COPYRIGHT PBRMISSION Knowledge and Perception of Lyme Disease in Manitoba: lmplications for Risk Assessment By Kathleen Crang A Thesis/PI'acticum submitted to the Faculty of Gracluatc Stutlies of Thc Uniyersitv of Manitob¿r in ¡rartial fulfillrnent of the req uire ment of the degrce of Master of Environment Kathleen CrangO2009 Permission has been grantecl to the Universit),of Manitob¿r Libraries to lcnd a copy of this thesis/practicum, to Library and Archives Canatla (LAC) to lencl ¿r cop)¡ of this thesis/¡lr.acticum, arltl to LAC's agent (UMI/ProQuest) to microfilm, sellcopies and to publish an ¿rbstract of this thesis/¡r racticu rn. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been rn¿rde available by ¿ruthority of the copyright olner solely for the purpose of private study ancl research, ancl may onl5, 5" reir.oducerl ana copiea :rs permittecl by copyright lan's or lvith express rvritten authorization from the copyright on,ner. Table of Contents Abstract.... iv Acknowledgements.... .......... v List of Tab1es............. .... vi List of Figures............. .......... vii Permission List for Copyrighted Material ....... viii Chapter I: Introduction............. I Literature Review. 2 Research Objectives and Questions... ..... 11 Chapter II: Research Methods ..... 13 Chapter III: Ecology and Epidemiology of Lyme Disease. -

Das Komplementsystem

Die Bedeutung verschiedener CRASP-Proteine für die Komplementresistenz von Borrelia burgdorferi s.s. Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Naturwissenschaften vorgelegt beim Fachbereich Biowissenschaften der Johann Wolfgang Goethe - Universität in Frankfurt am Main von Corinna Siegel aus Sebnitz Frankfurt 2010 (D 30) vom Fachbereich Biowissenschaften der Johann Wolfgang Goethe - Universität als Dissertation angenommen. Dekan: Prof. Dr. A. Starzinski-Powitz Gutachter: Prof. Dr. V. Müller Prof. Dr. P. Kraiczy Datum der Disputation: Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ..................................................................................................... I Abkürzungsverzeichnis ........................................................................................ VIII I. Einleitung ........................................................................................................... 1 1 Die Multisystemkrankheit Lyme-Borreliose ........................................................... 1 2 Der Überträger Ixodes spp. ................................................................................... 2 3 Charakteristika des Erregers B. burgdorferi s.l. .................................................... 3 3. 1 Taxonomie und Morphologie ......................................................................... 4 3. 2 Das Genom ................................................................................................... 6 3. 3 Genetische Manipulation von B. burgdorferi s.l. ........................................... -

Prevalence of Borrelia Burgdorferi Sensu Lato in Ixodes Ricinus Ticks in Scandinavia

Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Scandinavia Rikke Rollum Thesis for the Master’s degree in Molecular Biosciences 60 study points Department of Molecular Biosciences Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences UNIVERSITY OF OSLO 2014 II © Rikke Rollum 2014 Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Scandinavia Supervisors: Vivian Kjelland (UiA), Hans Petter Leinås (UiO), Audun Slettan (UiA) http://www.duo.uio.no/ Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo III IV Acknowledgements This master thesis was partly funded by the ScandTick project, which is a transnational project in Scandinavia devoted to ticks and tick-borne diseases. The laboratory work was conducted at the Department of Natural Sciences at the University of Agder (UiA) as an external thesis from the University of Oslo (UiO). I want to acknowledge all the people at UiO and UiA who have guided and helped me during my thesis. Vivian Kjelland (UiA), my supervisor, who gave me the opportunity to use her lab and for always being helpful, thorough and positive, which I really appreciate. You have inspired me to explore my opportunities, build connections and to be more confident and independent – Thank you! Audun Slettan (UiA), my co-supervisor, for always having a cheerful attitude and keeping my courage up when things did not go exactly as planned. I am also grateful to Hans Petter Leinaas (UiO), my co-supervisor, who have guided me in the writing process and for not letting me get carried away in fun facts. I would also like to thank Lars Korslund (UiA), who have helped me to understand and interpret the value of my results from a statistical point of view. -

Diagnosis of Lyme Disease by Kinetic Enzyme-Linked Immunosor- Bent Assay Using Recombinant Vlse1 Or Peptide Antigens of Borrelia Burg- (Ix) the Use of B

CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY REVIEWS, July 2005, p. 484–509 Vol. 18, No. 3 0893-8512/05/$08.00ϩ0 doi:10.1128/CMR.18.3.484–509.2005 Copyright © 2005, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved. Diagnosis of Lyme Borreliosis Maria E. Aguero-Rosenfeld,1,4* Guiqing Wang,2 Ira Schwartz,2 and Gary P. Wormser3,4 Departments of Pathology,1 Microbiology and Immunology,2 and Medicine,3 Division of Infectious Diseases, New York Medical College, and Westchester Medical Center,4 Valhalla, New York INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................484 CHARACTERISTICS OF B. BURGDORFERI........................................................................................................485 B. burgdorferi Genospecies .....................................................................................................................................485 LYME BORRELIOSIS: DISEASE SPECTRUM....................................................................................................486 LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS....................................................................................................................................486 Direct Detection of B. burgdorferi .........................................................................................................................486 Culture of B. burgdorferi sensu lato .................................................................................................................487 -

Borrelia Burgdorferi Surface-Localized Proteins Expressed During Persistent Murine Infection

Borrelia burgdorferi surface-localized proteins expressed during persistent murine infection and the importance of BBA66 during infection of C3H/HeJ mice by Jessica Lynn Hughes Bachelor of Science, University of Washington, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the School of Medicine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2008 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF MEDICINE This dissertation was presented by Jessica Lynn Hughes It was defended on April 3, 2008 and approved by Saleem A. Khan, Ph.D., Microbiology and Molecular Genetics Jeffrey G. Lawrence, Ph.D., Biological Sciences Bruce A. McClane, Ph.D., Microbiology and Molecular Genetics Ted M. Ross, Ph.D., Microbiology and Molecular Genetics Dissertation Advisor: James A. Carroll, Ph.D., Microbiology and Molecular Genetics ii Borrelia burgdorferi surface-localized proteins expressed during persistent murine infection and the importance of BBA66 during infection of C3H/HeJ mice Jessica Lynn Hughes, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2008 Select members of the group Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato are the causative agents of Lyme disease (LD), a multisystem, potentially chronic disorder with debilitating clinical manifestations including Lyme arthritis, carditis, and neuroborreliosis. Current knowledge regarding the expression of virulence factors encoded by B. burgdorferi and the breadth of their distribution amongst Borrelia species within or beyond the sensu lato group is limited. Some genes historically categorized into paralogous gene family (pgf) 54 have been suggested to be important during transmission to and/or infection of mammalian hosts. By studying the factors affecting the expression of this gene family and its encoded proteins, their distribution, and the disease profile of a bba66 deletion isolate, we aimed to determine the importance of pgf 54 genes in Lyme disease and their conservation amongst diverse Borrelia species. -

Molecular Biology of Borrelia Burgdorferi Sensu Lato in Latvia

Biomedical Research and Study Centre University of Latvia Riga, Latvia Molecular biology of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Latvia Renate Ranka Academic dissertation 2004 /-- Supervisor: ~ Professor, Dr.BioI., MD Viesturs Baumanis Opponents: Professor Sven Bergstrom, Urnea University, Sweden 1: Professor, Dr.Hab.Biol. Pauls Pumpens, University of Latvia Professor, Dr.Med. Juta Kroica, Riga Stradin's University, Latvia. Author's address: Biomedical Research and Study Centre, University of Latvia, Laboratory of Molecular Microbiology Ratsupites str 1, Riga, LATVIA, LV-1067 Fax: 371 7442407; Tel: 371 7808218 e-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. LIST OF ABBREVIA nONS AND TERMS 3 2. INTR 0DUerr ON 4 3. PAPERS IN THIS THESIS 6 4. REVIEW OF THE LITERA TURE 7 4.1. Main characteristics of Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes 7 4.2. Molecular biology of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato 9 4.3. Natural cycle and vectors of Borrelia burgdorferi 11 4.4. Lyme disease \-l 4.5. Immunologic testing in diagnosis of Lyme disease 16 4.6. Borrelia burgdorferi proteins and their immunogenetic properties 17 5. AIMS OF 'nus THESIS 20 6. METHODS 21 6.1. Collection of ticks 21 6.2. Microscopic detection of Borrelia in questing ticks 21 6.3. Cultivation of Borrelia burgdorferi 21 6.4. Reference DNA 21 6.5. DNA extraction 22 6.6. B. burgdorferi detection by PCR amplification 22 6.7. Molecular typing of B. burgdorferi by 16S-23S ribosomal DNA spacer PCR- RFLP 23 6.8. Molecular typing of B. burgdorferi by species-specific PCR targeted 16S rRNA gene "" 23 6.9. -

Renata Cunha Madureira

UFRRJ INSTITUTO DE VETERINÁRIA CURSO DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS VETERINÁRIAS TESE Sorologia para Borrelia burgdorferi em eqüinos do Estado do Pará e caracterização genotípica de isolados de Borrelia spp. Renata Cunha Madureira 2007 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL RURAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO INSTITUTO DE VETERINÁRIA CURSO DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS VETERINÁRIAS SOROLOGIA PARA Borrelia burgdorferi EM EQÜINOS DO ESTADO DO PARÁ E CARACTERIZAÇÃO GENOTÍPICA DE ISOLADOS DE Borrelia spp. RENATA CUNHA MADUREIRA Sob a Orientação do Professor Adivaldo Henrique da Fonseca e Co-orientação da Doutora Grácia Maria Soares Rosinha Tese submetida como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Doutor em Ciências, no Curso de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Veterinárias, Área de Concentração em Sanidade Animal. Seropédica, RJ Setembro de 2007 UFRRJ / Biblioteca Central / Divisão de Processamentos Técnicos 636.108969 24 Madureira, Renata Cunha, 1977- M183s Sorologia para Borrelia T burgdorferi em eqüinos do Estado do Pará e caracterização genotípica de isolados de Borrelia spp. / Renata Cunha Madureira. – 2007. 73f. : il. Orientador: Adivaldo Henrique da Fonseca. Tese (doutorado) – Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro, Instituto de Veterinária. Bibliografia: f. 49-60. 1. Eqüino – Doenças – Pará – Teses. 2. Eqüino – Imunologia – Teses. 3. Borrelia burgdorferi – Teses. 4. Imunodiagnóstico – Teses. I. Fonseca, Adivaldo Henrique da, 1953-. II. Universidade Federal Rural do Rio de Janeiro. Instituto de Veterinária. III. Título. Bibliotecário: _______________________________ Data: ___/___/______ Dedico essa tese a minha família: meus pais Marcos e Carmen Lucia; minha irmã Gabriela e a minha pequena sobrinha Carolina, que me dão força, segurança e coragem para nunca desistir de meus sonhos. Ao mestre, Prof. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Molecular characterization of the lyme disease spirochetes Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato Wang, G. Publication date 1999 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wang, G. (1999). Molecular characterization of the lyme disease spirochetes Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 Captée MOLECULAR TYPING OF BORRE LIA BURGDORFERI SENSU LATO: TAXONOMIC, EPIDEMIOLOGICAL AND CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS Guiqing Wang1, Alje P. van Dam', Ira Schwartz2, and Jacob Dankert' Department of Medical Microbiology, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, Meibergdreef 15, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, New York Medical College, Valhalla, New York 10595, U.SA. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, submitted Chapter 2 SUMMARY Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, the bacterium that causes human Lyme borreliosis (LB), has been cultured from various biological and geographic sources worldwide since its first discovery in 1982. -

Biological Aspects of Lyme Disease Spirochetes: Unique Bacteria of the Borrelia Burgdorferi Species Group

Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2007, 151(2):175–186. 175 © M. Krupka, M. Raska, J. Belakova, M. Horynova, R. Novotny, E. Weigl BIOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF LYME DISEASE SPIROCHETES: UNIQUE BACTERIA OF THE BORRELIA BURGDORFERI SPECIES GROUP Michal Krupkaa*, Milan Raskaa, Jana Belakovaa, Milada Horynovaa, Radko Novotnyb, Evzen Weigla a Department of Immunology, Faculty of Medicine, Hnevotinska 3, Palacky University, 775 15 Olomouc, Czech Republic b Department of Microscopy Methods, Faculty of Medicine, Hnevotinska 3, Palacky University, 775 15 Olomouc, Czech Republic *e-mail: [email protected] Received: September 15, 2007; Accepted: November 28, 2007 Key words: Borrelia burgdorferi/Lyme disease/Spirochete Background: Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato is a group of at least twelve closely related species some of which are responsible for Lyme disease, the most frequent zoonosis in Europe and the USA. Many of the biological features of Borrelia are unique in prokaryotes and very interesting not only from the medical viewpoint but also from the view of molecular biology. Methods: Relevant recent articles were searched using PubMed and Google search tools. Results and Conclusion: This is a review of the biological, genetic and physiological features of the spirochete species group, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. In spite of a lot of recent articles focused on B. burgdorferi sensu lato, many features of Borrelia biology remain obscure. It is one of the main reasons for persisting problems with preven- tion, diagnosis and therapy of Lyme disease. The aim of the review is to summarize ongoing current knowledge into a lucid and comprehensible form. INTRODUCTION In about 70 % of patients, the clinical picture of the disease starts as a pruriginous erythema at the site of the Lyme disease is a chronic multi-system infectious dis- tick bite.