Approaches to Prioritisation and Health Technology Assessment in New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kāinga Ora Governance Capability Uplift Programme

State Sector Governance Essentials – Kāinga Ora Governance Capability Uplift Programme Workbook iod.org.nz Workbook This workbook has been prepared as a resource for participants in the Institute of Directors in New Zealand (Inc) Director Development programme. It is not intended to be exhaustive or constitute advice. Its content should not be used or relied upon as a substitute for proper professional advice or as a basis for formulating business decisions. The Institute of Directors in New Zealand (Inc) and its employees expressly disclaim all or any liability or responsibility to any person in respect of this workbook and in respect of anything done or omitted to be done by any person in reliance on all or any part of the contents of the workbook. (March 2021) SSC 11996 A3 Poster v4 19/6/07 10:53 AM Page 1 A code of conduct issued by the State Services Commissioner under the State Sector Act 1988, section 57 WE MUST BE FAIR FAIR, IMPARTIAL, We must: – treat everyone fairly and with respect RESPONSIBLE & – be professional and responsive TRUSTWORTHY – work to make government services accessible and effective – strive to make a difference to the well-being of New Zealand and all its people. The State Services is made IMPARTIAL up of many organisations with powers to carry out the work of We must: New Zealand’s democratically – maintain the political neutrality required to enable us to work with elected governments. current and future governments – carry out the functions of our organisation, unaffected by our Whether we work in a department personal beliefs or in a Crown entity, we must act – support our organisation to provide robust and unbiased advice with a spirit of service to the – respect the authority of the government of the day. -

BCAC Submission to the Health Select Committee Re: Terre Maize Petition for Funding of Ibrance and Kadcyla 4 March 2019

1 BCAC Submission to the Health Select Committee re: Terre Maize petition for funding of Ibrance and Kadcyla 4 March 2019 2 Contents Breast Cancer Aotearoa Coalition ....................................................................................................... 3 Why we are making this submission ................................................................................................... 4 BCAC’s experience with PHARMAC ..................................................................................................... 4 Summary of issues with PHARMAC .................................................................................................... 6 Outline of PHARMAC’s process for listing medicines ......................................................................... 6 Time taken to fund currently available breast cancer treatments ..................................................... 7 Key treatments that New Zealanders with breast cancer are currently missing out on .................... 8 Impacts of PHARMAC’s performance in breast cancer medicines on New Zealand’s health system and society ........................................................................................................................................ 13 BCAC’s rebuttal of statements made in PHARMAC’s submission to the Health Select Committee . 14 BCAC’s rebuttal of statements made in the Ministry of Health’s submission to the Health Select Committee ....................................................................................................................................... -

Safe and Qual Ty Use of Med C

Safe and Qualty Use of Medcnes 2005–2007 Report Safe and Quality Use of Medicines: 2005–2007 report Citation: SQM. 2008. Safe and Quality Use of Medicines 2005–2007 Report. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Published in January 2009 by the Ministry of Health PO Box 5013, Wellington, New Zealand ISBN 978-0-478-31893-7 (Print) ISBN 978-0-478-31894-4 (Online) HP 4744 This document is available on the SQM website: http://www.safeuseofmedicines.co.nz Safe and Quality Use of Medicines: 2005–2007 report Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. v Chapter 1: Medication Safety ...................................................................................................1 Chapter 2: National Safe and Quality Use of Medicines Strategy: Progress against SQM Strategy Goals and Objectives .................................................................................................4 Chapter 3: Leadership and National Co-ordination ..................................................................5 Chapter 4: Best Practice Prescribing, Dispensing and Administration .....................................7 Chapter 5: High-risk Medicines and High-risk Situations .......................................................10 Chapter 6: Systems, Processes, Technology and Information Systems ................................14 Chapter 7: Primary Care and the Primary/Secondary Interface ............................................17 Chapter 8: Audit, Evaluation, -

Reports of Select Committees on the 2017/18 Annual Reviews Of

I.20D Reports of select committees on the 2017/18 annual reviews of Government departments, Offices of Parliament, Crown entities, public organisations, and State enterprises Volume 1 Financial Statements of the Government for the year ended 30 June 2018 Economic Development and Infrastructure Sector Education Sector Environment Sector External Sector Finance and Government Administration Sector Fifty-second Parliament April 2019 Presented to the House of Representatives I.20D Contents Crown entity/public Select Committee Date presented Page organisation/State enterprise Financial Statements of the Finance and Expenditure 22 Feb 2019 1 Government of New Zealand for the year ended 30 June 2018 Economic Development and Infrastructure Sector Accident Compensation Education and Workforce 5 Apr 2019 14 Corporation Accreditation Council Economic Development, 5 Apr 2019 23 Science and Innovation AgResearch Limited Economic Development, 5 Apr 2019 24 Science and Innovation Air New Zealand Limited Transport and Infrastructure 5 Apr 2019 29 Airways Corporation of New Transport and Infrastructure 5 Apr 2019 29 Zealand Limited Callaghan Innovation Economic Development, 5 Apr 2019 30 Science and Innovation City Rail Link Limited Transport and Infrastructure 5 Apr 2019 36 Civil Aviation Authority of New Transport and Infrastructure 5 Apr 2019 39 Zealand Commerce Commission Economic Development, 5 Apr 2019 42 Science and Innovation Crown Infrastructure Partners Transport and Infrastructure 5 Apr 2019 48 Limited (previously called Crown Fibre Holdings -

New Zealand Health System Review

Health Systems in Transition Vol. 4 No. 2 2014 New Zealand Health System Review Health Systems in Transition Vol. 4 No. 2 2014 New Zealand Health System Review Written by: Jacqueline Cumming, Victoria University of Wellington Janet McDonald, Victoria University of Wellington Colin Barr, Victoria University of Wellington Greg Martin, Victoria University of Wellington Zac Gerring, Victoria University of Wellington Jacob Daubé, Victoria University of Wellington Wellington, New Zealand Edited by: Christian Gericke, The Wesley Research Institute and University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia i WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data New Zealand health system review (Health Systems in Transition, Vol.4 No. 2 2014) 1. Delivery of health care. 2. Health care economics and organization. 3. Health care reform. 4. Health systems plans – organization and administration. 5. New Zealand. I. Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. II. World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. ISBN: 978 92 9061 650 4 (NLM Classification: WA 950) © World Health Organization 2014 (on behalf of the Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies) All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). For WHO Western Pacific Regional Publications, request for permission to reproduce should be addressed to the Publications Office, World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific, P.O. -

The Wellbeing Budget 2019

B.2 THE WELLBEING BUDGET 30 May 2019 ISBN: 978-1-98-858041-8 (print), 978-1-98-858042-5 (online) THE WELLBEING BUDGET A new frontline Tackling service for mental Reaching 5,600 homelessness, TAKING health with a Suicide prevention MENTAL extra secondary with 1,044 new $455m programme services get a HEALTH students with more places – Housing SERIOUSLY providing access $40m boost nurses in schools First will now reach for 325,000 people 2,700 people by 2023/24 Breaking the Taking financial Specialist services cycle for children pressure off Lifting incomes IMPROVING as part of a $320m in State care, parents by by indexing main CHILD package to address including helping increasing funding benefitsand WELLBEING family and 3,000 young to decile 1-7 schools removing punitive sexual violence people into so they don’t need sanctions independent living to ask for donations Major boost for An additional Ensuring te reo SUPPORTING Whānau Ora, 2,200 young A $12m programme MĀORI AND Māori and Pacific including a focus on people in the targeting PASIFIKA languages survive ASPIRATIONS health and reducing Pacific Employment rheumatic fever and thrive reoffending Support Service Bridging the Nearly $200m set Opportunities for $106m injection venture capital aside for vocational apprenticeships into innovation to BUILDING A gap, with a $300m education reforms for nearly 2,000 PRODUCTIVE help New Zealand fund so start-ups to boost young people NATION transition to a can grow and apprenticeships through Mana low‑carbon future succeed and trade training in -

State of the State New Zealand 2016 Social Investment for Our Future Foreword

State of the State New Zealand 2016 Social investment for our future Foreword We believe New Zealand is the best place in the world As such, we welcome the government’s moves to widen to live, work and play. Over the years, successive the use of the investment approach in social services, governments have played a significant role in including in the recently announced reforms to Child, making New Zealand the great place it is today. Our Youth and Family. It is only by making an impact on government’s finances are in good shape, despite the the lives of those most at risk of poor outcomes – not global financial crisis and the Canterbury earthquakes, just children but across all social services – that we can and our research shows they are even better when you ensure we maintain all that is good about New Zealand. compare us to other developed nations. A long term view is exactly what we need. But we cannot rest. New Zealand shares the challenges The challenges to the wider implementation of social of an ageing population, low productivity and revenue investment are not trivial. Some run into the very growth, and the need to reduce government debt, with culture and fabric of the way our public sector is run many other nations. We must tackle these challenges and managed. Success requires the government to today to maintain our way of life in the future. start taking more calculated risks to push the envelope on the positive difference we can make in people’s More importantly, new data shows that for some of lives. -

NZMJ 1499.Indd

Journal of the New Zealand Medical Association Vol 132 | No 1499 | 26 July 2019 Older New Zealanders: addressing an emerging population of hazardous drinkers Doctors’ rights to conscientiously object to refer patients to abortion service providers Unplanned pregnancies of Subsequent injuries experienced What we know, and don’t women with chronic health by Māori: results from a 24-month know, about cannabis, conditions in New Zealand prospective study in New Zealand psychosis and violence Publication Information published by the New Zealand Medical Association NZMJ Editor NZMA Chair Professor Frank Frizelle Dr Kate Baddock NZMJ Production Editor NZMA Communications Manager Rory Stewart Diana Wolken Other enquiries to: NZMA To contribute to the NZMJ, fi rst read: PO Box 156 www.nzma.org.nz/journal/contribute The Terrace Wellington 6140 © NZMA 2019 Phone: (04) 472 4741 To subscribe to the NZMJ, email [email protected] Subscription to the New Zealand Medical Journal is free and automatic to NZMA members. Private subscription is available to institutions, to people who are not medical practitioners, and to medical practitioners who live outside New Zealand. Subscription rates are below. All access to the NZMJ is by login and password, but IP access is available to some subscribers. Read our Conditions of access for subscribers for further information www.nzma.org.nz/journal/subscribe/conditions-of-access If you are a member or a subscriber and have not yet received your login and password, or wish to receive email alerts, please email: [email protected] The NZMA also publishes the NZMJ Digest. This online magazine is sent out to members and subscribers 10 times a year and contains selected material from the NZMJ, along with all obituaries, summaries of all articles, and other NZMA and health sector news and information. -

New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act 2000

Reprint as at 1 July 2012 New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act 2000 Public Act 2000 No 91 Date of assent 14 December 2000 Commencement see section 2 Contents Page 1 Title 7 Part 1 Preliminary provisions 2 Commencement 7 3 Purpose 7 4 Treaty of Waitangi 8 5 Outline 9 6 Interpretation 11 7 Act to bind the Crown 17 Part 2 Responsibilities of Minister 8 Health and disability strategies 17 9 Strategies for standards and quality assurance programmes 18 10 Crown funding agreements 19 Note Changes authorised by section 17C of the Acts and Regulations Publication Act 1989 have been made in this reprint. A general outline of these changes is set out in the notes at the end of this reprint, together with other explanatory material about this reprint. This Act is administered by the Ministry of Health. 1 New Zealand Public Health and Reprinted as at Disability Act 2000 1 July 2012 11 Ministerial committees 20 12 Information about committees to be made public 20 13 National advisory committee on health and disability 22 14 Public health advisory committee 22 15 Health workforce advisory committee 23 16 National advisory committee on health and disability 23 support services ethics 17 National health epidemiology and quality assurance 24 advisory committee [Repealed] 18 Mortality review committees [Repealed] 25 Part 3 District Health Boards 19 Establishment of DHBs 25 20 Process for restructuring geographical areas of DHBs 26 21 Application of Crown Entities Act 2004 to DHBs 26 22 Objectives of DHBs 27 23 Functions of DHBs 28 24 Co-operative -

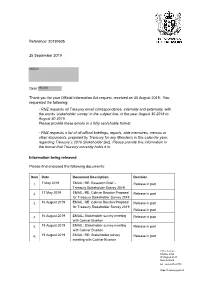

Official Information Act Response 20190605

Reference: 20190605 25 September 2019 s9(2)(a) Dear s9(2)(a) Thank you for your Official Information Act request, received on 30 August 2019. You requested the following: - RNZ requests all Treasury email correspondence, internally and externally, with the words ‘stakeholder survey’ in the subject line, in the year August 30 2018 to August 30 2019. Please provide these emails in a fully searchable format. - RNZ requests a list of all official briefings, reports, aide memoires, memos or other documents, prepared by Treasury for any Minister/s in this calendar year, regarding Treasury’s 2019 Stakeholder [sic]. Please provide this information in the format that Treasury currently holds it in. Information being released Please find enclosed the following documents: Item Date Document Description Decision 1. 7 May 2019 EMAIL: RE: Research Brief – Release in part Treasury Stakeholder Survey 2019 2. 17 May 2019 EMAIL: RE: Colmar Brunton Proposal Release in part for Treasury Stakeholder Survey 2019 3. 16 August 2019 EMAIL: RE: Colmar Brunton Proposal Release in part for Treasury Stakeholder Survey 2019 Release in part 4. 16 August 2019 EMAIL: Stakeholder survey meeting Release in part with Colmar Brunton 5. 19 August 2019 EMAIL: Stakeholder survey meeting Release in part with Colmar Brunton 6. 19 August 2019 EMAIL: RE: Stakeholder survey Release in part meeting with Colmar Brunton 1 The Terrace PO Box 3724 Wellington 6140 New Zealand tel. +64-4-472-2733 https://treasury.govt.nz 7. 30 August 2019 EMAIL: RE: 2019 Stakeholder Release in part Engagement Survey - your stakeholder lists by COB next Thursday please! 8. -

COVID-19 Health System Response Monitor New Zealand

COVID-19 Health System Response Monitor New Zealand April 2021 Author Dr Jacqueline Cumming, Independent Health Services Research and Policy Consultant Advisor, Waikanae Beach, New Zealand World Health Organization Regional Office for South‐East Asia COVID‐19 health system response monitor: New Zealand ISBN 978‐92‐9022‐846‐2 © World Health Organization 2021 (on behalf of the Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies) Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution Non‐Commercial Share Alike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY‐NC‐SA. 3.0 IGO. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by‐nc‐sa/3.0/igo/). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adopt the work for non‐commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adopt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition.” Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization (http://www.wipo.int.amc/en/mediation.rules). -

B20-Sum-Initiatives-Crrf.Pdf

Summary of Initiatives IN THE COVID-19 RESPONSE AND RECOVERY FUND (CRRF) FOUNDATIONAL PACKAGE Hon Grant Robertson Minister of Finance 29 May 2020 © Crown copyright This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. In essence, you are free to copy, distribute and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the work to the Crown and abide by the other licence terms. To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Please note that no departmental or governmental emblem, logo or Coat of Arms may be used in any way which infringes any provision of the Flags, Emblems, and Names Protection Act 1981. Attribution to the Crown should be in written form and not by reproduction of any such emblem, logo or Coat of Arms. Budget 2020 website URL: Permanent URL: budget.govt.nz/budget/2020/summary-initiatives.htm treasury.govt.nz/publications/summary-intiatives/summary- initiatives-crrf-budget2020 CONTENTS BACKGROUND TO THE CRRF 1 CRRF FOUNDATIONAL PACKAGE 1 DETAILED BREAKDOWN OF INITIATIVES BY VOTE 2 HOW TO READ THE INITIATIVE TABLES 2 NEW INITIATIVES 3 Agriculture, Biosecurity, Fisheries and Food Safety 3 Arts, Culture and Heritage 5 Business, Science and Innovation 7 Conservation 10 Corrections 11 Courts 12 Customs 12 Defence Force 13 Education 13 Environment 15 Health 15 Housing and Urban Development 16 Internal Affairs 17 Justice 18 Labour Market 19 Lands 20 Māori Development 21 Oranga Tamariki 22 Pacific Peoples 22 Police 23 Prime Minister and Cabinet 24 Revenue 24 Serious Fraud 24 Social Development 25 Sport and Recreation 27 Tertiary Education 28 Transport 30 i BUDGET 2020 SUMMARY OF INITIATIVES IN THE COVID-19 RESPONSE AND RECOVERY FUND (CRRF) FOUNDATIONAL PACKAGE As indicated on Budget Day we are releasing this Summary of Initiatives document to complement the Wellbeing Budget 2020 document and the media releases detailing expenditure funded from the COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund (CRRF).