Du Plessis Donotella 2017.Pdf (2.074Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metro Response to Public Comments Proposed License for Grimm's Fuel

Metro response to public comments Proposed license for Grimm’s Fuel Company Metro response to public comments received during the comment period in October through November 2018 regarding proposed license conditions for Grimm’s Fuel Company. Prepared by Hila Ritter January 4, 2019 BACKGROUND Grimm’s Fuel Company (Grimm’s), is a locally-owned and operated Metro-licensed yard debris composting facility that primarily accepts yard debris for composting. In general, Metro’s licensing requirements for a composting facility set conditions for receiving, managing, and transferring yard debris and other waste at the facility. The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) also has distinct yet complementary requirements for composting facilities and monitors environmental impacts of facilities to protect air, soil, and water quality. Metro and DEQ work closely together to provide regulatory oversight of solid waste facilities such as Grimm’s. On October 22, 2018, Metro opened a formal public comment period for several new conditions of the draft license for Grimm’s. The public comment period closed on November 30, 2018. Metro also hosted a community conversation during that time to further solicit input and discuss next steps. During the formal comment period, Metro received 119 written comments from individuals and businesses (attached). Metro received an additional six written comments via email after the comment period closed at 5 p.m. on November 30, which did not become an official part of the record. After the comment period closed, members of the Tualatin community requested that Metro extend the term of Grimm’s current license for an additional two months to allow the public an opportunity to review the new proposed license in its entirety before it is issued. -

Grimm Season 3 Torrent

Grimm Season 3 Torrent 1 / 4 Grimm Season 3 Torrent 2 / 4 3 / 4 Here you can download TV show Grimm (season 1, 2, 3, 4, 5) full episodes in mp4 mkv and avi. All episodes are available in HD quality 720p, 1080p for free.. New episodes of the popular television series for PC you can get from moviestrunk.com. Latest episodes of Grimm download here! Unlike kickass and Torrent .... Grimm TV Series Complete Season 1,2,3,4,5,6 Torrent Download. Drama,Fantasy,Horror(2011-) IMD-7.8/10. Grimm Season 01 Download. Download Grimm season 3 complete episodes download for free. No registration needed. All episodes of Grimm season 3 complete episodes download .... ... Annette O'Toole, John Schneider; Features: 11" x 17" Packaged with care - ships in sturdy reinforced packing material Made in the USA SHIPS IN 1-3 DAYS.. Download Grimm Season 3 Complete torrent from series & tv category on Isohunt.. Tlcharger Bionic.Woman.SAISON.1.FRENCH en torrent.. Starring: David Giuntoli,Russell Hornsby,Bitsie Tulloch Verified Torrent. Download torrent. Grimm torrent. Good rate 14 Bad rate 4. Storyline:. In Season 3 of this supernatural drama, Nick (David Giuntoli) deals with some surprising aftereffects of his zombie attack?and the outcome is more positive than .... Supernatural detective drama criminal police (played by David Giuntoli) hiding among us in human form with the participation of two natures.. 02/04/12--08:50: Grimm Season 1 Episode 3 - BeeWare ... 01 - 14 Frame size: 352 x 624 [b]PLEASE SEED TORRENT ONCE YOU HAVE DOWNLOADED IT[/b] .... ... and an executioner, the “other” means the law, they are men. -

Mothers Grimm Kindle

MOTHERS GRIMM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Danielle Wood | 224 pages | 01 Oct 2016 | Allen & Unwin | 9781741756746 | English | St Leonards, Australia Mothers Grimm PDF Book Showing An aquatic reptilian-like creature that is an exceptional swimmer. They have a temper that they control and release to become effective killers, particularly when a matter involves a family member or loved one. She took Nick to Weston's car and told Nick that he knew Adalind was upstairs with Renard, and the two guys Weston sent around back knew too. When Wu asks how she got over thinking it was real, she tells him that it didn't matter whether it was real, what mattered was losing her fear of it. Dick Award Nominee I found the characters appealing, and the plot intriguing. This wesen is portrayed as the mythological basis for the Three Little Pigs. The tales are very dark, and while the central theme is motherhood, the stories are truly about womanhood, and society's unrealistic and unfair expectations of all of us. Paperback , pages. The series presents them as the mythological basis for The Story of the Three Bears. In a phone call, his parents called him Monroe, seeming to indicate that it is his first name. The first edition contained 86 stories, and by the seventh edition in , had unique fairy tales. Danielle is currently teaching creative writing at the University of Tasmania. The kiss of a musai secretes a psychotropic substance that causes obsessive infatuation. View all 3 comments. He asks Sean Renard, a police captain, to endorse him so he would be elected for the mayor position. -

An Analysis of the Devil in the Original Folk and Fairy Tales

Syncretism or Superimposition: An Analysis of the Devil in The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm Tiffany Stachnik Honors 498: Directed Study, Grimm’s Fairy Tales April 8, 2018 1 Abstract Since their first full publication in 1815, the folk and fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm have provided a means of studying the rich oral traditions of Germany. The Grimm brothers indicated time and time again in their personal notes that the oral traditions found in their folk and fairy tales included symbols, characters, and themes belonging to pre-Christian Germanic culture, as well as to the firmly Christian German states from which they collected their folk and fairy tales. The blending of pre-Christian Germanic culture with Christian, German traditions is particularly salient in the figure of the devil, despite the fact that the devil is arguably one of the most popular Christian figures to date. Through an exploration of the phylogenetic analyses of the Grimm’s tales featuring the devil, connections between the devil in the Grimm’s tales and other German or Germanic tales, and Christian and Germanic symbolism, this study demonstrates that the devil in the Grimm’s tales is an embodiment of syncretism between Christian and pre-Christian traditions. This syncretic devil is not only consistent with the history of religious transformation in Germany, which involved the slow blending of elements of Germanic paganism and Christianity, but also points to a greater theme of syncretism between the cultural traditions of Germany and other -

Download Season 5 Grimm Free Watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1 Online

download season 5 grimm free Watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1 Online. On Grimm Season 5 Episode 1, Nick struggles with how to move forward after the beheading of his mother, the death of Juliette and Adalind being pregnant. Watch Similar Shows FREE Amazon Watch Now iTunes Watch Now Vudu Watch Now YouTube Purchase Watch Now Google Play Watch Now NBC Watch Now Verizon On Demand Watch Now. When you watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1 online, the action picks up right where the season finale of Grimm Season 4 left off, with Juliette dead in Nick's arms, Nick's mother's severed head in a box, and Agent Chavez's goons coming to kidnap Trubel. Nick is apparently drugged, and when he awakes, there is no sign that any of this occurred: no body, no box, no head, no Trubel. Was it all a truly horrible dream? Or part of a larger conspiracy? When he tries to tell his friends what happened, they hesitate to believe his claims, especially when he lays the blame at the feet of Agent Chavez. As his mental state deteriorates, will Nick be able to discover the truth about what happened and why? Where is Trubel now, and why did Chavez and her people come to kidnap her? Will his friends ever believe him, or will they continue to doubt his claims about what happened? And what will Nick do now that his and Adalind's baby is on the way? Tune in and watch Grimm Season 5 Episode 1, "The Grimm Identity," online right here at TV Fanatic to find out what happens. -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

VR White-Paper.Indd

Virtual Reality at Grimm + Parker Architects Date: November 2, 2017 By: Antonio Rebelo AIA, Director of Design (Grimm + Parker Architects), in collaboration with John Schippers Contact: [email protected] 301.595.1000 Since the beginning of recorded design, the search for a method of conveying an idea of a three-dimensional space or environment that didn’t yet exist in physical form, encouraged the creation of perspective views, the perfection of hand painted renderings, sketches and even scaled down physical models throughout history. The practical necessity to “see” and even “feel” a three-dimensional space to test for proportion, light, materiality, context and a multitude of other elements, has been at the core of architecture practice since its inception. This need has been there to fulfi ll two basic requirements of the design process: to help the designer transform abstract ideas into form, by allowing for study through the iterative design process, and second, to off er others (colleagues, clients and the community) a means for the visualization of the designer’s intent and the client’s vision. With the advent of computer aided design and advance in technology, the profes- sion has seen a rapid evolution towards ever more realistic renderings and visualization in ways that were almost inconceivable in the past, such as full immersive virtual reality. From a client’s perspective, this evolution in technology couldn’t be better news! Instead Grimm + Parker Architects 11720 Beltsville Dr, Ste #600 of relying on imagination by trying to understand traditional 2D fl oor plans and elevations, Calverton, MD 20705 which can be notoriously diffi cult, even if these were paired with illustrations of interior Tel: 301.595.1000 and exterior spaces, virtual reality and full 3D design off er a much easier way to process Visit online at grimmandparker.com architectural information than ever before - for everyone. -

Subscribe to the Press & Dakotan Today!

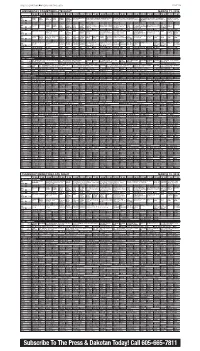

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, MARCH 6, 2015 PAGE 9B WEDNESDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT MARCH 11, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Odd Wild Cyber- Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You 50 Years With Peter, Paul and Mary Perfor- John Sebastian Presents: Folk Rewind NOVA The tornado PBS (DVS) Squad Kratts Å chase Speaks Business Stereo) Å Finding financial solutions. (In Stereo) Å mances by Peter, Paul and Mary. (In Stereo) Å (My Music) Artists of the 1950s and ’60s. (In outbreak of 2011. (In KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å Stereo) Å KTIV $ 4 $ Meredith Vieira Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent Myst-Laura Law & Order: SVU Chicago PD News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Mysteries of Law & Order: Special Chicago PD Two teen- KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å Å Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Laura A star athlete is Victims Unit Å (DVS) age girls disappear. News Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (In Stereo) Å With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory killed. Å Å (DVS) (N) Å (In Stereo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

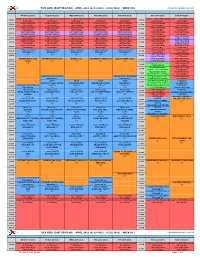

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

From Tenino to Ghana

Halloween Edition Thursday, Oct. 31, 2013 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Battle of the Swamp W.F. West to Take On Centralia in Rivalry Classic / Inside Food Stamp Increase Expires REDUCTION: Cuts Depend the American Recovery and Rein- maximum benefit, for example, will vestment Act, which raised Supple- see a reduction of $29 a month from on Income, Expenses mental Nutrition Assistance Pro- $526 to $497. By Lisa Broadt gram benefits to help people affected A single adult receiving the maxi- by the recession. [email protected] mum benefit will go from $189 to Monthly food benefits vary based $178. The federal government’s tem- on factors such as income, living ex- Pete Caster / [email protected] Households that receive help porary boost in food assistance pro- penses and the number of people in through the state-funded Food Lisa and Jerry Morris stand outside the Lewis County oice of grams ends Friday. the household. the Department of Social and Health Service in Chehalis Oct. 2. In April 2009, Congress passed A family of three receiving the please see FOOD, page Main 11 Overbay, Students Gather Books and Supplies, Sending Support Others to Headline From Tenino to Ghana ‘Men’s Night Out’ ADVICE: Prostate Cancer Survivor, Lyle Overbay and Health Experts to Share Experiences at Tuesday Forum By Kyle Spurr [email protected] Arnie Guenther, a retired Centralia banker, avoided the doctor’s office for physical checkups until last year when his wife finally convinced him to make an appointment. Guenther felt fine, but results from the checkup showed he had prostate cancer. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Eric Laneuville Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ)

Eric Laneuville Филм ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (ФилмографиÑ) Exposed https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/exposed-5421584/actors Maréchaussée https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mar%C3%A9chauss%C3%A9e-26214860/actors Cry Lusion https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/cry-lusion-18644046/actors The Grimm Identity https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-grimm-identity-27070622/actors PTZD https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ptzd-15930037/actors The Other Side https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-other-side-16639708/actors The Inheritance https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-inheritance-26025124/actors Key Move https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/key-move-29097907/actors The Other Woman https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-other-woman-1050294/actors Red Badge https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/red-badge-105095288/actors Red Herring https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/red-herring-105095322/actors Pink Chanel Suit https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/pink-chanel-suit-105095359/actors Like a Redheaded Stepchild https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/like-a-redheaded-stepchild-105095404/actors Little Red Book https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/little-red-book-105095422/actors The Redshirt https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-redshirt-105095436/actors Ruddy Cheeks https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ruddy-cheeks-105095453/actors Days of Wine and Roses https://bg.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/days-of-wine-and-roses-105095500/actors Red Listed