The Chat Vol 76 No 1 Winter 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

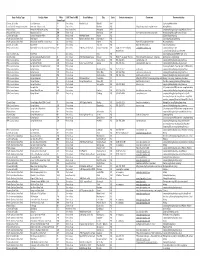

Sorted by Facility Type.Xlsm

Basic Facility Type Facility Name Miles AVG Time In HRS Street Address City State Contact information Comments Known activities (from Cary) Comercial Facility Ace Adventures 267 5 hrs or less Minden Road Oak Hill WV Kayaking/White Water East Coast Greenway Association American Tobacco Trail 25 1 hr or less Durham NC http://triangletrails.org/american- Biking/hiking Military Bases Annapolis Military Academy 410 more than 6 hrs Annapolis MD camping/hiking/backpacking/Military History National Park Service Appalachian Trail 200 5 hrs or less Damascus VA Various trail and entry/exit points Backpacking/Hiking/Mountain Biking Comercial Facility Aurora Phosphate Mine 150 4 hrs or less 400 Main Street Aurora NC SCUBA/Fossil Hunting North Carolina State Park Bear Island 142 3 hrs or less Hammocks Beach Road Swannsboro NC Canoeing/Kayaking/fishing North Carolina State Park Beaverdam State Recreation Area 31 1 hr or less Butner NC Part of Falls Lake State Park Mountain Biking Comercial Facility Black River 90 2 hrs or less Teachey NC Black River Canoeing Canoeing/Kayaking BSA Council camps Blue Ridge Scout Reservation-Powhatan 196 4 hrs or less 2600 Max Creek Road Hiwassee (24347) VA (540) 777-7963 (Shirley [email protected] camping/hiking/copes Neiderhiser) course/climbing/biking/archery/BB City / County Parks Bond Park 5 1 hr or less Cary NC Canoeing/Kayaking/COPE/High ropes Church Camp Camp Agape (Lutheran Church) 45 1 hr or less 1369 Tyler Dewar Lane Duncan NC Randy Youngquist-Thurow Must call well in advance to schedule Archery/canoeing/hiking/ -

Raven Rock: Then and Now. Medoc Mountain State Park: an Environmental Education Learning Experience Designed for Grades 5-7

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 376 037 SE 054 737 AUTHOR Brown, David G. TITLE Raven Rock: Then and Now. Medoc Mountain State Park: An Environmental Education Learning Experience Designed for Grades 5-7. INSTITUTION North Carolina State Dept. of Environment, Health, and Natural Resources, Raleigh. Div. of Parkt A Recreation. PUB DATE Jan 94 NOTE 59p.; For related guides, see SE 054 736-744 and SE 054 746. AVAILABLE FROMNorth Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation, P.O. Box 27687, Raleigh, NC 27611-7687. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Instructional Materials (For Learner)(051) Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Classification; Educational Games; Environmental Education; Equipment; *Geology; Grade 5; Grade 6; Grade 7;Intermediate Grades; Junior High Schools; *Mineralogy; *Minerals; Parks; *Petrology; Science Activities; Science Education; *Topography IDENTIFIERS Environmental Awareness; Erosion; Hands On Experience; Hiking; *Mountains; *North Carolina State Parks System ABSTRACT This activity guide, developed to provide environmental education through a series of hands-on activities geared to Raven Rock State Park in North Carolina, is targeted for grades 5, 6, and 7 and meets curriculum objectives of the standard course of study established by the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. Three types of activities are included: pre-visit, on-site, and post-visit. The on-site activity is conducted at the park, while pre- and post-visit activities are designed for the classroom. Major concepts included are: rock cycle geomorphology; formation of sedimentary, metamorphic, and igneous rocks; weathering and erosion, rock and mineral characteristics; and topography. Includes a vocabulary list, scLeduling worksheet, parental permission form, North Carolina Parks and Recreation program evaluation and information about Raven Rock State Park. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G3862 SOUTHERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3862 FEATURES, ETC. .C55 Clayton Aquifer .C6 Coasts .E8 Eutaw Aquifer .G8 Gulf Intracoastal Waterway .L6 Louisville and Nashville Railroad 525 G3867 SOUTHEASTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3867 FEATURES, ETC. .C5 Chattahoochee River .C8 Cumberland Gap National Historical Park .C85 Cumberland Mountains .F55 Floridan Aquifer .G8 Gulf Islands National Seashore .H5 Hiwassee River .J4 Jefferson National Forest .L5 Little Tennessee River .O8 Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail 526 G3872 SOUTHEAST ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, G3872 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .B6 Blue Ridge Mountains .C5 Chattooga River .C52 Chattooga River [wild & scenic river] .C6 Coasts .E4 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Area .N4 New River .S3 Sandhills 527 G3882 VIRGINIA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G3882 .A3 Accotink, Lake .A43 Alexanders Island .A44 Alexandria Canal .A46 Amelia Wildlife Management Area .A5 Anna, Lake .A62 Appomattox River .A64 Arlington Boulevard .A66 Arlington Estate .A68 Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial .A7 Arlington National Cemetery .A8 Ash-Lawn Highland .A85 Assawoman Island .A89 Asylum Creek .B3 Back Bay [VA & NC] .B33 Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge .B35 Baker Island .B37 Barbours Creek Wilderness .B38 Barboursville Basin [geologic basin] .B39 Barcroft, Lake .B395 Battery Cove .B4 Beach Creek .B43 Bear Creek Lake State Park .B44 Beech Forest .B454 Belle Isle [Lancaster County] .B455 Belle Isle [Richmond] .B458 Berkeley Island .B46 Berkeley Plantation .B53 Big Bethel Reservoir .B542 Big Island [Amherst County] .B543 Big Island [Bedford County] .B544 Big Island [Fluvanna County] .B545 Big Island [Gloucester County] .B547 Big Island [New Kent County] .B548 Big Island [Virginia Beach] .B55 Blackwater River .B56 Bluestone River [VA & WV] .B57 Bolling Island .B6 Booker T. -

Nc State Parks

GUIDE TO NC STATE PARKS North Carolina’s first state park, Mount Mitchell, offers the same spectacular views today as it did in 1916. 42 OUR STATE GUIDE to the GREAT OUTDOORS North Carolina’s state parks are packed with opportunities: for adventure and leisure, recreation and education. From our highest peaks to our most pristine shorelines, there’s a park for everyone, right here at home. ACTIVITIES & AMENITIES CAMPING CABINS MILES 5 THAN MORE HIKING, RIDING HORSEBACK BICYCLING CLIMBING ROCK FISHING SWIMMING SHELTER PICNIC CENTER VISITOR SITE HISTORIC CAROLINA BEACH DISMAL SWAMP STATE PARK CHIMNEY ROCK STATE PARK SOUTH MILLS // Once a site of • • • CAROLINA BEACH // This coastal park is extensive logging, this now-protected CROWDERSMOUNTAIN • • • • • • home to the Venus flytrap, a carnivorous land has rebounded. Sixteen miles ELK KNOB plant unique to the wetlands of the of trails lead visitors around this • • Carolinas. Located along the Cape hauntingly beautiful landscape, and a GORGES • • • • • • Fear River, this secluded area is no less 2,000-foot boardwalk ventures into GRANDFATHERMOUNTAIN • • dynamic than the nearby Atlantic. the Great Dismal Swamp itself. HANGING ROCK (910) 458-8206 (252) 771-6593 • • • • • • • • • • • ncparks.gov/carolina-beach-state-park ncparks.gov/dismal-swamp-state-park LAKE JAMES • • • • • LAKE NORMAN • • • • • • • CARVERS CREEK STATE PARK ELK KNOB STATE PARK MORROW MOUNTAIN • • • • • • • • • WESTERN SPRING LAKE // A historic Rockefeller TODD // Elk Knob is the only park MOUNT JEFFERSON • family vacation home is set among the in the state that offers cross- MOUNT MITCHELL longleaf pines of this park, whose scenic country skiing during the winter. • • • • landscape spans more than 4,000 acres, Dramatic elevation changes create NEW RIVER • • • • • rich with natural and historical beauty. -

Regional Recreation Evaluation Final Study Report FERC No

Alcoa Power Generating Inc. Yadkin Division Yadkin Project Relicensing (FERC No. 2197) Regional Recreation Evaluation Final Study Report April 2005 Table of Contents SUMMARY.................................................................................................................................... 1 1.0 Introduction...................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Study Purpose.................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Study Methods................................................................................................................. 3 1.2.1 Data Collection....................................................................................................... 3 1.2.2 Regional Recreation Review................................................................................... 3 1.2.3 Characterization of Regional Recreation Resources............................................... 6 1.2.4 Comparison of Yadkin Project Recreation Resources with Other Regional Resources ................................................................................................................ 9 1.2.5 Review of Yadkin Area Recreation Plans and Future Opportunities ..................... 9 2.0 Yadkin Project Recreation Resources.............................................................................. 9 2.1 High Rock Reservoir....................................................................................................... -

North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation Contact Information for Individual Parks

North Carolina Division of Parks and Recreation Contact information for individual parks Parks A to K CAROLINA BEACH State Park CARVERS CREEK State Park CHIMNEY ROCK State Park 910-458-8206 910-436-4681 828-625-1823 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] P.O. Box 475 2505 Long Valley Road P.O. Box 220 Carolina Beach, NC 28428 Spring Lake, NC 28390 Chimney Rock, NC 28720 CLIFFS OF THE NEUSE State Park CROWDERS MOUNTAIN State Park DISMAL SWAMP State Park 919-778-6234 704-853-5375 252-771-6593 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 240 Park Entrance Road 522 Park Office Lane 2294 U.S. 17 N. Seven Springs, NC 28578 Kings Mountain, NC 28086 South Mills, NC 27976 ELK KNOB State Park ENO RIVER State Park FALLS LAKE State Rec Area 828-297-7261 919-383-1686 919-676-1027 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 5564 Meat Camp Road 6101 Cole Mill Road 13304 Creedmoor Road Todd, NC 28684 Durham, NC 27705 Wake Forest, NC 27587 FORT FISHER State Rec Area FORT MACON State Park GOOSE CREEK State Park 910-458-5798 252-726-3775 252-923-2191 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 1000 Loggerhead Road 2303 E. Fort Macon Road 2190 Camp Leach Road Kure Beach, NC 28449 Atlantic Beach, NC 28512 Washington, NC 27889 GORGES State Park GRANDFATHER MTN State Park HAMMOCKS BEACH State Park 828-966-9099 828-963-9522 910-326-4881 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 976 Grassy Ridge Road P.O. -

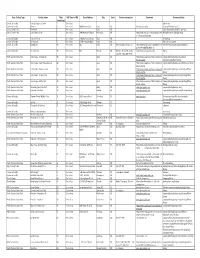

Sorted by Miles from Cary.Xlsm

Basic Facility Type Facility Name Miles AVG Time In HRS Street Address City State Contact information Comments Known activities (from Cary) Comercial Facility Triangle Aquatics Center 2 1 hr or less Swimming Comercial Facility Glenaire 4 1 hr or less 400 Glenaire Circle Cary NC Good pack activity Singing Christmas carols City / County Parks Bond Park 5 1 hr or less Cary NC Canoeing/Kayaking/COPE/High ropes City / County Parks Lake Crabtree Park 5 1 hr or less 1400 Aviation Parkway Morrisville NC http://www.wakegov.com/parks/lakecrab Biking/Mountain Biking/boating tree/Pages/default.aspx Comercial Facility Polar Ice House 5 1 hr or less 1410 Buck Jones Road Cary NC Ice skating Comercial Facility RU A Gamer 5 1 hr or less 218 Nottingham Drive Cary NC Video Arcade Games Comercial Facility Oddfellows 10 1 hr or less RDU Cary NC [email protected] http://www.rtpnet.org/troop200/forms/R Primitive Camping/Backpacking/Biking DU-CAMP-ODDFELLOWS.doc Comercial Facility Young Eagles 10 1 hr or less RDU Raleigh NC Raleigh - Richard Netherby - http://www.youngeagles.org/ Flying EAA 879 (919) 608-2316 North Carolina State Park Jordan Lake - Crosswinds 10 1 hr or less Apex NC http://www.ncparks.gov/Visit/parks/jord/ camping/hiking/backpacking/board directions.php sailing/boating/Water Skiing North Carolina State Park Jordan Lake - New Hope Overlook 10 1 hr or less Apex NC http://www.ncparks.gov/Visit/parks/jord/ camping/hiking/backpacking/Primitive camping directions.php North Carolina State Park Jordan Lake - Parkers Creek 10 1 hr or less Apex NC -

Drawing the Natural Gardens of North Carolina, by Betty Lou Chaika Certificate in Native Plant Studies, North Carolina Botanical Garden, Chapel Hill October, 2013

Drawing the Natural Gardens of North Carolina, by Betty Lou Chaika Certificate in Native Plant Studies, North Carolina Botanical Garden, Chapel Hill October, 2013. Advisor: Steph Jeffries Abstract The Drawing the Natural Gardens project was initiated to bridge between the Botanical Illustration and Native Plant Studies programs by combining drawing and ecology. The goals of the project were a) to show the possibilities of nature journaling or field sketching for getting to know plant communities, plant/animal interactions among species, and plant interactions with their environments; b) to introduce others to the wonderful beauty and diversity of our North Carolina natural gardens and generate interest in saving what we have left. The project included visiting and drawing many of our North Carolina habitats in Mountains, Piedmont, and Coastal Plain and creating visual/verbal narratives of seasonal ecological observations, recording a slice of place at a point in time. Each drawing is an overview of a particular community on a particular day in a particular season, as observed in the field. This report contains scans of most of the sketchbook’s double-page spreads, which show how the drawings evolved from field sketches to studio- completed drawings, and includes some supplementary information about these habitats. For those of us who live here, North Carolina is our homeland. It is our special Place. Within the vast landscape of this beautiful state there are a wonderful variety of different natural habitats. Each habitat, with its unique combination of elements (elevation, topography, types of rock and soil, temperature, moisture) is home to special groupings of plants and animals. -

Systemwide Plan for North Carolina State Parks 2009

Systemwide Plan for North Carolina State Parks 2009 N.C. Division of Parks and Recreation N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources Systemwide Plan for North Carolina State Parks 2009 Division of Parks and Recreation Department of Environment and Natural Resources EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The years from 2000 through 2008 were a period of unprecedented growth for the North Carolina State Parks System. In 2000, the NC General Assembly established a goal of protecting one million acres of open space lands. Funding was provided through several state trust funds, as well as special indebtedness, and the state parks system underwent an historic, carefully planned expansion. • Land acquisition added 46,340 acres to the system, and 15 new units, including state parks, state natural areas, and state trails, were authorized by the General Assembly. Land acquisition funding from fiscal year 1999-2000 through fiscal year 2007-2008 totaled $276.1 million. • Two nationally known landmarks were added to the state parks system. Chimney Rock was added to Hickory Nut Gorge State Park in 2007, and the park’s name was changed to Chimney Rock. The undeveloped portions of Grandfather Mountain became a state park in 2009. • From fiscal year 1999-2000 through fiscal year 2007-2008, $139.3 million was made available to the state parks system for construction of new facilities and for repairs and improvements to existing facilities. • Major advances have been made in interpretation and education, natural resource stewardship, planning, trails, and all other programmatic areas. Field staff positions increased from 314 in 1999 to 428 in 2008 to manage new lands and operate new park facilities. -

Scenic Byways

n c s c e n i c b y w a y s a h c rol rt in o a n fourth edition s c s en ay ic byw North Carolina Department of Transportation Table of ConTenTs Click on Byway. Introduction Legend NCDOT Programs Rules of the Road Cultural Resources Blue Ridge Parkway Scenic Byways State Map MOuntains Waterfall Byway Nantahala Byway Cherohala Skyway Indian Lakes Scenic Byway Whitewater Way Forest Heritage Scenic Byway appalachian Medley French Broad Overview Historic Flat Rock Scenic Byway Drovers Road Black Mountain Rag Pacolet River Byway South Mountain Scenery Mission Crossing Little Parkway New River Valley Byway I-26 Scenic Highway u.S. 421 Scenic Byway Pisgah Loop Scenic Byway upper Yadkin Way Yadkin Valley Scenic Byway Smoky Mountain Scenic Byway Mt. Mitchell Scenic Drive PIedmont Hanging Rock Scenic Byway Colonial Heritage Byway Football Road Crowders Mountain Drive Mill Bridge Scenic Byway 2 BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS BACK TO BYWAYS MAP Table of ConTenTs uwharrie Scenic Road Rolling Kansas Byway Pee Dee Valley Drive Grassy Island Crossing Sandhills Scenic Drive Birkhead Wilderness Route Flint Hill Ramble Indian Heritage Trail Pottery Road Devil’s Stompin’ Ground Road North Durham Country Byway averasboro Battlefield Scenic Byway Clayton Bypass Scenic Byway Scots-Welsh Heritage Byway COastaL PLain Blue-Gray Scenic Byway Meteor Lakes Byway Green Swamp Byway Brunswick Town Road Cape Fear Historic Byway Lafayette’s Tour Tar Heel Trace edenton-Windsor Loop Perquimans Crossing Pamlico Scenic Byway alligator River Route Roanoke Voyages Corridor Outer Banks Scenic Byway State Parks & Recreation areas Historic Sites For More Information Bibliography 3 BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS BACK TO BYWAYS MAP inTroduction The N.C. -

N C S C E N I C B Y W a Y S

NC SCENIC BYWAYS a hc rol rt in o a n fourth edition s c s en ay ic byw North Carolina Department of Transportation TABLE OF CONTENTS Click on Byway. Introduction 4 Legend 5 NCDOT Programs 6 Rules of the Road 8 Cultural Resources 11 Blue Ridge Parkway 12 Scenic Byways State Map 14 MOUntAins Waterfall Byway 18 Nantahala Byway 21 Cherohala Skyway 24 Indian Lakes Scenic Byway 26 Whitewater Way 28 Forest Heritage Scenic Byway 30 Appalachian Medley 32 French Broad Overview 35 Historic Flat Rock Scenic Byway 37 Drovers Road 39 Black Mountain Rag 41 Pacolet River Byway 43 South Mountain Scenery 44 Mission Crossing 46 Little Parkway 48 New River Valley Byway 50 I-26 Scenic Highway 52 U.S. 421 Scenic Byway 55 Pisgah Loop Scenic Byway 57 Upper Yadkin Way 60 PIEdmont Hanging Rock Scenic Byway 64 Colonial Heritage Byway 66 Football Road 68 Crowders Mountain Drive 70 2 BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS BACK TO BYWAYS MAP BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS BACK TO BYWAYS MAP TABLE OF CONTENTS Mill Bridge Scenic Byway 72 Uwharrie Scenic Road 74 Rolling Kansas Byway 76 Pee Dee Valley Drive 78 Grassy Island Crossing 80 Sandhills Scenic Drive 82 Birkhead Wilderness Route 84 Flint Hill Ramble 86 Indian Heritage Trail 88 Pottery Road 90 Devil’s Stompin’ Ground Road 92 North Durham Country Byway 94 Averasboro Battlefield Scenic Byway 97 Scots-Welsh Heritage Byway 99 COAstAl PLAin Blue-Gray Scenic Byway 104 Meteor Lakes Byway 108 Green Swamp Byway 110 Brunswick Town Road 112 Cape Fear Historic Byway 114 Lafayette’s Tour 118 Tar Heel Trace 123 Edenton-Windsor Loop 125 Perquimans Crossing 128 Pamlico Scenic Byway 130 Alligator River Route 134 Roanoke Voyages Corridor 137 Outer Banks Scenic Byway 139 State Parks & Recreation Areas 144 Historic Sites 152 For More Information 168 Bibliography 170 3 BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS BACK TO BYWAYS MAP BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS BACK TO BYWAYS MAP INTRODUctION The N.C. -

Cape Fear River Basin Is One of Four River (2000 U.S

RIVER CAPE FEAR BASIN he 200-mile Cape Fear River is the main tributary and namesake of the state’s largest Triver basin. It is the only river in North Carolina that flows directly into the ocean. The river draws its name from the treacherous profile: offshore shoals (dubbed the “Cape of Feare” by Total miles of early mariners). The shoals stretch for miles into streams and rivers: the Atlantic Ocean from the river’s mouth. The Cape 6,584 Fear River and its tributaries were important pathways for early Total acres of lakes: commerce through the historic ports of Brunswick, Charlestown 34,796 COURTESY OF N.C. ARCHIVES AND HISTORY and Wilmington. In the mid-1800s, the Cape Total acres of estuary: 24,472 Fear was an outlet for the commercial products of more than 28 counties. River trade extended Municipalities within basin: 113 up to Fayetteville through a series of three locks and dams that raised the water level. Through - Counties within basin: 26 out the 19th century, shallow-draft steamboats called at more than 100 local landings between Size: 9,164 square miles Fayetteville and Wilmington. Population: 1,757,366 The Cape Fear River Basin is one of four river (2000 U.S. Census) Historic steamboat basins completely contained within North Carolina’s borders. The head- waters (origin) of the basin are the Deep and Haw rivers. These rivers An oil tanker travels up converge in Chatham County just below B. Everett Jordan Dam to form the Cape Fear River 15 the Cape Fear River . The river ends as a 35-mile-long coastal estuary miles below Wilmington.