The Afterman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'From Beneath the Waves'.Pdf

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Beasts of the Deep: Sea Creatures and Popular Culture A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library Contents ISBN: 9780 86196 733 9 (Paperback); 9780 86196 939 5 (Ebook) Acknowledgements vii Introduction: Beasts of the Deep Part 1: FOLKLORE AND WEIRD TALES 9 Chapter 1 "From Beneath the Waves": Sea-Draugr and the Popular Conscience,Alexander Hay 11 Chapter 2 The Depths of our Experience: Thalassophobia and the Oceanic Horror, Sean J. Harrington 27 Chapter 3 From Depths of Terror to Depths of Wonder: The Sublime in Lovecraft's 'Call of Cthulhu' and Cameron's The Abyss, VivanJoseph 42 Part 2: DEPTHS OF DESIRE 57 Chapter 4 Beauty and the Octopus: Close encounters with the other-than-human, Marco Benoit Carbone 59 Chapter 5 The Octopussy: Exploring representations offemale sexuality in Victor Hugo's The Toilers of the Sea (1866) and The Laughing Man (1868), Laura Ettenfield 78 Chapter 6 Psychedelic Deep Blues: the Romanticised Sea Creature in Jimi Hendrix's '1983... (A Merman I Should Turn to Be)' (1968), Tim Buckley's 'Song to the Siren' (1968) and Captain Beefheart's 'Grow Fins' (1972), Richard Mills 94 Part 3: AQUATIC SPACES AND PRACTICES 109 Chapter 7 Fan Totems: Affective Investments in the Sea Creatures of Horror and Science Fiction, Brigid Cherry 111 Chapter 8 Mermaid Spotting: the Rise of Mermaiding in Popular Culture, Maria Mellins 128 Chapter 9 Adventures in Liquid Space: Representations of the Sea in Disney Theme Parks, Lee Brooks 142 Chapter 10 Rivers of Blood, -

Norse Monstrosities in the Monstrous World of J.R.R. Tolkien

Norse Monstrosities in the Monstrous World of J.R.R. Tolkien Robin Veenman BA Thesis Tilburg University 18/06/2019 Supervisor: David Janssens Second reader: Sander Bax Abstract The work of J.R.R. Tolkien appears to resemble various aspects from Norse mythology and the Norse sagas. While many have researched these resemblances, few have done so specifically on the dark side of Tolkien’s work. Since Tolkien himself was fascinated with the dark side of literature and was of the opinion that monsters served an essential role within a story, I argue that both the monsters and Tolkien’s attraction to Norse mythology and sagas are essential phenomena within his work. Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Chapter one: Tolkien’s Fascination with Norse mythology 7 1.1 Introduction 7 1.2 Humphrey Carpenter: Tolkien’s Biographer 8 1.3 Concrete Examples From Jakobsson and Shippey 9 1.4 St. Clair: an Overview 10 1.5 Kuseela’s Theory on Gandalf 11 1.6 Chapter Overview 12 Chapter two: The monsters Compared: Midgard vs Middle-earth 14 2.1 Introduction 14 2.2 Dragons 15 2.3 Dwarves 19 2.4 Orcs 23 2.5 Wargs 28 2.6 Wights 30 2.7 Trolls 34 2.8 Chapter Conclusion 38 Chapter three: The Meaning of Monsters 41 3.1 Introduction 41 3.2 The Dark Side of Literature 42 3.3 A Horrifically Human Fascination 43 3.4 Demonstrare: the Applicability of Monsters 49 3.5 Chapter Conclusion 53 Chapter four: The 20th Century and the Northern Warrior-Ethos in Middle-earth 55 4.1 Introduction 55 4.2 An Author of His Century 57 4.3 Norse Warrior-Ethos 60 4.4 Chapter Conclusion 63 Discussion 65 Conclusion 68 Bibliography 71 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost I have to thank the person who is evidently at the start of most thesis acknowledgements -for I could not have done this without him-: my supervisor. -

A Saga of Odin, Frigg and Loki Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DARK GROWS THE SUN : A SAGA OF ODIN, FRIGG AND LOKI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Matt Bishop | 322 pages | 03 May 2020 | Fensalir Publishing, LLC | 9780998678924 | English | none Dark Grows the Sun : A saga of Odin, Frigg and Loki PDF Book He is said to bring inspiration to poets and writers. A number of small images in silver or bronze, dating from the Viking age, have also been found in various parts of Scandinavia. They then mixed, preserved and fermented Kvasirs' blood with honey into a powerful magical mead that inspired poets, shamans and magicians. Royal Academy of Arts, London. Lerwick: Shetland Heritage Publications. She and Bor had three sons who became the Aesir Gods. Thor goes out, finds Hymir's best ox, and rips its head off. Born of nine maidens, all of whom were sisters, He is the handsome gold-toothed guardian of Bifrost, the rainbow bridge leading to Asgard, the home of the Gods, and thus the connection between body and soul. He came round to see her and entered her home without a weapon to show that he came in peace. They find themselves facing a massive castle in an open area. The reemerged fields grow without needing to be sown. Baldur was the most beautiful of the gods, and he was also gentle, fair, and wise. Sjofn is the goddess who inclines the heart to love. Freyja objects. Eventually the Gods became weary of war and began to talk of peace and hostages. There the surviving gods will meet, and the land will be fertile and green, and two humans will repopulate the world. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: O Lynn, Aidan Anthony Title: Ghosts of War and Spirits of Place Spectral Belief in Early Modern England and Protestant Germany General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Ghosts of Place and Spirits of War: Spectral Belief in Early Modern England and Protestant Germany Aidan Anthony O’Lynn A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts School of History August 2018 Word Count: 79950 i Abstract This thesis focuses on themes of place and war in the development of ghostlore in Early Modern Protestant Germany and England. -

Orkney's Terrible Trows

By Carolyn Emerick Orkney’s Terrible Trows Waking Trows from 1918 Danish Postcard Other Illustrations by John Bauer, c 1910s Trows are fascinating creatures found only in Apparently, Orkney mythology merges the folklore of the Orkney and Shetland islands. Fairies and Trows, making it unclear if they are Yet, describing them accurately is difficult the same species, or if they were once separate because sources are not always clear. creatures that merged over hundreds of years Folklorists have long insisted that the word of storytelling. Sometimes the words are used “trow” is a corruption of “troll,” and that interchangeably. Orkney’s Trows descend from their Viking In his book of Orkney folk tales, storyteller ancestors’ stories of Trolls. Sigurd Towrie, Tom Muir admits that even he can’t suss it out. author of the comprehensive website covering He says “In Orkney the word [Trow] has been all things Orkney (Orkneyjar.com), disagrees mixed up with the fairy, so it is hard to say if we with this assessment. He believes there may are dealing with one or more type of creature. In be a connection with a different creature from the text of this book I have used the name given Norse mythology, the Draugr. This connection by the person who told the story” (Muir, xi). stems from both creatures’ affiliation with This highlights the huge discrepancy between burial mounds. The Draugr were undead tomb contemporary and previous conceptions of guardians who harassed any trespassers, whether Fairies. Most people today would not identify human or animal, who dared to come too close a “trollish” creature as either a fairy or a to his mound. -

The History of English Podcast Transcripts Episodes

THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH PODCAST TRANSCRIPTS EPISODES 41 -45 Presented by Kevin W. Stroud ©2012-2020 Seven Springs Enterprises, LLC TABLE OF CONTENTS Episode 41: New Words From Old English . 1 Episode 42: Beowulf and Other Viking Ancestors . 18 Episode 43: Anglo-Saxon Monsters and Mythology . 33 Episode 44: The Romance of Old French . 49 Episode 45: To Coin a Phrase – and Money . 67 EPISODE 41 - NEW WORDS FROM OLD ENGLISH Welcome to the History of English Podcast - a podcast about the history of the English language. This is Episode 41: New Words From Old English. In this episode, we’re going to explore the how the Anglo-Saxons expanded their vocabulary by creating new words from old words. This included putting two or more existing words together to create new compound words. It also included the use of prefixes and suffixes – many of which survive into Modern English. And once we’ve explored this process, we’re going to see how this new expanded vocabulary combined with the expansion of learning to make Old English a true literary language – capable of producing sophisticated literature, including the most well-known work in Old English – Beowulf. A quick note before we begin. This episode is about words – lots of words. In fact, this episode is probably more ‘word-heavy’ than any other episode. And that’s because I want to illustrate how the Anglo-Saxons were constantly creating new words within Old English. And all of those new words ultimately allowed English to emerge as a fully mature literary language. It is important to keep in mind that the original Germanic language was a very basic ‘earthy’ language. -

Icelandic Folklore

i ICELANDIC FOLKLORE AND THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF RELIGIOUS CHANGE ii BORDERLINES approaches,Borderlines methodologies,welcomes monographs or theories and from edited the socialcollections sciences, that, health while studies, firmly androoted the in late antique, medieval, and early modern periods, are “edgy” and may introduce sciences. Typically, volumes are theoretically aware whilst introducing novel approaches to topics of key interest to scholars of the pre-modern past. iii ICELANDIC FOLKLORE AND THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF RELIGIOUS CHANGE by ERIC SHANE BRYAN iv We have all forgotten our names. — G. K. Chesterton Commons licence CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. This work is licensed under Creative British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. © 2021, Arc Humanities Press, Leeds The author asserts their moral right to be identi�ied as the author of this work. Permission to use brief excerpts from this work in scholarly and educational works is hereby granted determinedprovided that to thebe “fair source use” is under acknowledged. Section 107 Any of theuse U.S.of material Copyright in Act this September work that 2010 is an Page exception 2 or that or limitation covered by Article 5 of the European Union’s Copyright Directive (2001/ 29/ EC) or would be 94– 553) does not require the Publisher’s permission. satis�ies the conditions speci�ied in Section 108 of the U.S. Copyright Act (17 USC §108, as revised by P.L. ISBN (HB): 9781641893756 ISBN (PB): 9781641894654 eISBN (PDF): 9781641893763 www.arc- humanities.org print-on-demand technology. -

Download Download

Dan Laurin THE EVERLASTING DEAD: SIMILARITIES BETWEEN THE HOLY SAINT AND THE HORRIFYING DRAUGR OS MORTOS ETERNOS: SEMELHANÇAS ENTRE O SANTO SAGRADO E O HORRIFICANTE DRAUGR Dan Laurin1 Abstract: The purpose of this article will be to examine the lives of different Icelandic and Continental Scandinavian saints in biskupasögur and compare them to the uniquely Icelandic revenant known as a draugr found mainly—but not limited to—the Íslendingasögur category. The morphology of the saint and the draugr will be analysed through the scope of the physical, behavioural, and supernatural motifs apparent in each literary figure. This approach will be useful to better understand a comparison between how each figure reconciles the concept of death and the afterlife, as well as their liminal grasp of corporeality which displays their similarity. Keywords: Icelandic sagas; Supernatural; Medieval literature; Draugr. Resumo: O objetivo deste artigo será examinar as vidas de diferentes santos escandinavos islandeses e continentais nas biskupasögur e compará-las ao morto-vivo exclusivamente islandês conhecido como draugr encontrado principalmente - mas não limitado na - categoria Íslendingasögur. A morfologia do santo e do draugr será analisada através do alcance dos motivos físicos, comportamentais e sobrenaturais aparentes em cada figura literária. Essa abordagem será útil para entender melhor uma comparação entre como cada figura concilia o conceito de morte e vida após a morte, bem como sua compreensão liminar da corporeidade que mostra sua semelhança. Palavras-chave: Sagas islandesas; Sobrenatural; Literatura medieval; Draugr. 1 Dan Laurin is a recent Medieval Master of Studies graduate from the University of Oxford, after having earned his Bachelor of Studies from the University of Berkeley, California. -

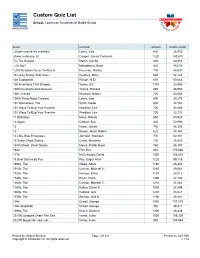

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Coachman Fundamental Middle School MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® WORD COUNT ¿Quién cuenta las estrellas? Lowry, Lois 680 26,950 último mohicano, El Cooper, James Fenimore 1220 140,610 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 40,955 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 98,676 1,000 Reasons Never To Kiss A Freeman, Martha 790 58,937 10 Lucky Things That Have Hershey, Mary 640 52,124 100 Cupboards Wilson, N. D. 650 59,063 100 Inventions That Shaped... Yenne, Bill 1370 33,959 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 38,950 1001 Cranes Hirahara, Naomi 720 43,080 100th Thing About Caroline Lowry, Lois 690 30,273 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 44,767 101 Ways To Bug Your Parents Wardlaw, Lee 700 37,864 101 Ways To Bug Your Teacher Wardlaw, Lee 700 52,733 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 650 50,929 12 Again Corbett, Sue 800 52,996 13 Howe, James 740 56,355 13 Brown, Jason Robert 620 38,363 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 770 62,401 13 Scary Ghost Stories Carus, Marianne 730 25,560 145th Street: Short Stories Myers, Walter Dean 760 36,397 1632 Flint, Eric 650 175,646 1776 McCullough, David 1300 105,034 18 Best Stories By Poe Poe, Edgar Allan 1220 99,118 1900s, The Woog, Adam 1160 26,484 1910s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1280 29,561 1920s, The Hanson, Erica 1170 28,812 1930s, The Press, Petra 1300 27,749 1940s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1210 31,665 1950s, The Kallen, Stuart A. -

A Comparative Study of Representations of Shape- Shifting in Old Norse and Medieval Irish Narrative Literature

Metamorphoses: a Comparative Study of Representations of Shape- Shifting in Old Norse and Medieval Irish Narrative Literature Camilla Michelle With Pedersen, BA Master of Literature / Research Master Maynooth University Department of Sean Ghaeilge (Early Irish) August 2015 Head of Department: Prof David Stifter Supervisor: Dr Elizabeth Boyle 1 Table of Content Introduction 4 Definitions of Metamorphosis and Metempsychosis 4 Philosophical Considerations about Metamorphosis 6 Education of the Early Irish and Medieval Scandinavian Period 8 Early Irish Sources 10 Old Norse Sources 12 Scope of the Study 16 I “Voluntary” Shape-Shifting 17 Irish Evidence 18 Fenian Cycle 18 Áirem Muintiri Finn 20 The Naming of Dún Gaire 24 Eachtach, Daughter of Diarmaid and Grainne 26 The Law Texts 28 Scandinavian Evidence 29 Definition of Berserkr/Berserkir 29 Egils saga Skallagrímssonar 32 Grettis saga Ásmundarsonar 34 Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks 35 Berserkir in King’ Retinue 36 Hólmganga 38 Female Berserkir 39 Transformation through Terror 42 Literal Metamorphosis 44 Vǫlsunga saga 44 Scél Tuáin Meic Chairill 47 De Chophur in da Muccida 49 2 Tochmarc Emire 51 Aislinge Óenguso 52 II “Involuntary” Shape-Shifting 54 Irish Evidence 55 Bran and Sceolang 55 Finn and the Man in the Tree 57 Tochmarc Étaíne 61 Aislinge Óenguso 65 The Story of the Abbot of Druimenaig 67 Scandinavian Evidence 69 Vǫlsunga saga 69 Laxdæla saga 70 Hrólfs saga Kraka 71 Draugr 72 III “Genetic” Shape-Shifting 80 De hominibus qui se uertunt in lupos 80 Egils saga Skallagrímssonar 83 Hrólfs saga Kraka 85 IV Cú Chulainn’s Ríastrad 90 The Three Descriptions of Cú Chulainn’s Ríastrad 91 Recension I 91 Recension II – Book of Leinster 93 The Stowe Manuscript 95 Discussion of Imagery 97 The Ríastrad and Transcendence 99 Conclusion 106 Bibliography 114 3 Introduction Definitions of Metamorphosis and Metempsychosis This study will consider literal and metaphorical metamorphosis representations of metamorphosis. -

Towards a Typology of Absence in Old Norse Literature

Exemplaria Medieval, Early Modern, Theory ISSN: 1041-2573 (Print) 1753-3074 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/yexm20 Towards a Typology of Absence in Old Norse Literature Richard Cole To cite this article: Richard Cole (2016) Towards a Typology of Absence in Old Norse Literature, Exemplaria, 28:2, 137-160, DOI: 10.1080/10412573.2016.1151201 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10412573.2016.1151201 Published online: 27 Apr 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=yexm20 Download by: [Harvard Library] Date: 27 April 2016, At: 08:08 EXEMPLARIA, Vol. 28 No. 2, March, 2016, 137–160 Towards a Typology of Absence in Old Norse Literature Richard Cole Harvard University, USA This essay accepts Patrick Fuery’s challenge to “get directly engaged in issues of typology” when considering absence. The powers of lost lovers, slain gods, and howling voids in Old Norse literature are anatomized according to the many phenomena denoted by the word “absence.” Demonstrating several species and differing degrees of absence, the essay also shows how each is created by a particular mechanism, and each tends towards specific emotional consequences. Each species of typology is illustrated with examples taken from Old Norse literature; yet its various types may well be applied beyond such contexts. KEYWORDS absence, Old Norse, Kormáks saga, Eyrbyggja saga, Snorra Edda, mythology, Gilles Deleuze. On the edge of the known world, Ívar Bárðarson travels around the deserted wastes of the Greenland colony, wondering what became of the thousands of souls who once lived there.1 On a moonlit night in an Icelandic dale, the monster slayer Grettir Ásmundarson Downloaded by [Harvard Library] at 08:08 27 April 2016 wrestles with his fear of the dark, tormented by visions of creatures that — as far as any other mortal knows — aren’t really there. -

Black Popular Culture

BLACK POPULAR CULTURE THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL AFRICOLOGY: A:JPAS THE JOURNAL OF PAN AFRICAN STUDIES Volume 8 | Number 2 | September 2020 Special Issue Editor: Dr. Angela Spence Nelson Cover Art: “Wakanda Forever” Dr. Michelle Ferrier POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 2 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State Bowling Green State University University University JUDITH FATHALLAH KATIE FREDRICKS KIT MEDJESKY Solent University Rutgers University University of Findlay JESSE KAVADLO ANGELA M.