Memorization & Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spaced Interval Repetition Technique

The Spaced Interval Repetition Technique What is it? The Spaced Interval Repetition (SIR) technique is a memorization technique largely developed in the 1960’s and is a phenomenal way of learning information very efficiently that almost nobody knows about. It is based on the landmark research in memory conducted by famous psychologist, Hermann Ebbinghaus in the late 19th century. Ebbinghaus discovered that when we learn new information, we actually forget it very quickly (within a matter of minutes and hours) and the more time that passes, the more likely we are to forget it (unless it is presented to us again). This is why “cramming” for the test does not allow you to learn/remember everything for the test (and why you don’t remember any of it a week later). SIR software, notably first developed by Piotr A. Woźniak is available to help you learn information like a superhero and even retain it for the rest of your life. The SIR technique can be applied to any kind of learning, but arguably works best when learning discrete pieces of information like dates, definitions, vocabulary, formulas, etc. Why does it work? Memory is a fickle creature. For most people, to really learn something, we need to rehearse it several times; this is how information gets from short‐term memory to long‐ term memory. Research tells us that the best time to rehearse something (like those formulas for your statistics class) is right before you are about to forget it. Obviously, it is very difficult for us to know when we are about to forget an important piece of information. -

Memorization Techniques

MEMORIZATION Memorization BasicsTECHNIQUES Putting information in long-term memory takes TIME and ORGANIZATION. This helps us consolidate information so it remains connected in our brains. Information is best learned when it is meaningful, authentic, engaging, and humorous (we learn 30% more when we tie humor to memory!). Rehearsing or reciting information is the key to retaining it long-term. Types of Memory There are three different types of memory: 1. Long-term: Permanent storehouse of information and can retain information indefinitely 2. Short-term: Working memory and can retain information for 20 to 30 seconds 3. Immediate: “In and out memory” which does not retain information If you want to do well on exams, you need to focus on putting your information into long-term memory. Why is Memorization Necessary? Individuals who read a chapter textbook typically forget: 46% after one day 79% after 14 days 81% after 28 days Sometimes, what we “remember” are invented memories. Events are reported that never took place; casual remarks are embellished, and major points are disregarded or downplayed. This is why it is important to take the time to improve your long-term memory. Memorization Tips 1. Put in the effort and time to improve your memorizing techniques. 2. Pay attention and remain focused on the material. 3. Get it right the first time; otherwise, your brain has a hard time getting it right after you correct yourself. 4. Chunk or block information into smaller, more manageable parts. Read a couple of pages at a time; take notes on key ideas, and review and recite the information. -

Learning Efficiency Correlates of Using Supermemo with Specially Crafted Flashcards in Medical Scholarship

Learning efficiency correlates of using SuperMemo with specially crafted Flashcards in medical scholarship. Authors: Jacopo Michettoni, Alexis Pujo, Daniel Nadolny, Raj Thimmiah. Abstract Computer-assisted learning has been growing in popularity in higher education and in the research literature. A subset of these novel approaches to learning claim that predictive algorithms called Spaced Repetition can significantly improve retention rates of studied knowledge while minimizing the time investment required for learning. SuperMemo is a brand of commercial software and the editor of the SuperMemo spaced repetition algorithm. Medical scholarship is well known for requiring students to acquire large amounts of information in a short span of time. Anatomy, in particular, relies heavily on rote memorization. Using the SuperMemo web platform1 we are creating a non-randomized trial, inviting medical students completing an anatomy course to take part. Usage of SuperMemo as well as a performance test will be measured and compared with a concurrent control group who will not be provided with the SuperMemo Software. Hypotheses A) Increased average grade for memorization-intensive examinations If spaced repetition positively affects average retrievability and stability of memory over the term of one to four months, then consistent2 users should obtain better grades than their peers on memorization-intensive examination material. B) Grades increase with consistency There is a negative relationship between variability of daily usage of SRS and grades. 1 https://www.supermemo.com/ 2 Defined in Criteria for inclusion: SuperMemo group. C) Increased stability of memory in the long-term If spaced repetition positively affects knowledge stability, consistent users should have more durable recall even after reviews of learned material have ceased. -

The Art of Loci: Immerse to Memorize

The Art of Loci: Immerse to Memorize Anne Vetter, Daniel Gotz,¨ Sebastian von Mammen Games Engineering, University of Wurzburg,¨ Germany fanne.vetter,[email protected], [email protected] Abstract—There are uncountable things to be remembered, but assistance during comprehension (R6) of the information, e.g. most people were never shown how to memorize effectively. With by means of verbalization, should follow suit. Due to the this paper, the application The Art of Loci (TAoL) is presented, heterogeneity of learners, the applied process and methods to provide the means for efficient and fun learning. In a virtual reality (VR) environment users can express their study material should be individualized (R7) and strike a productive balance visually, either creating dimensional mind maps or experimenting between user’s choices and imposed learning activities (locus with mnemonic strategies, such as mind palaces. We also present of control) (R8). For example, users should be able to control common memorization techniques in light of their underlying the pace of learning. Learning environments should arouse the pedagogical foundations and discuss the respective features of intrinsic motivation of the user (R9). Fostering an awareness TAoL in comparison with similar software applications. of the learner’s cognition and thus reflection on their learning I. INTRODUCTION process and strategies is also beneficial (metacognition) (R10). Further, a constructivist learning approach can be realized by Before writing was common, information could only be the means to create artefacts such as representations, symbols preserved by memorization. Major ancient literature like The or cues (R11). Finally, cooperative and collaborative learning Iliad and The Odyssey were memorized, passed on through environments can benefit the learning process (R12). -

Memorization Strategies

Memorization strategies Memorization Strategies - Do you have a hard - Do you wish you had time memorizing and better strategies to help you remembering memorize and remember information for tests? information? - Do the things you’ve - Do you sometimes feel the memorized seem to get information you need is mixed up in your head? there, but that you just can’t get to it? Whether you want to remember facts for a test or the name of someone you just met, remembering information is a skill that can be developed! Strategies that Work Strategies… Use all of your senses Look for logical connections The more senses you invovle in the learning process, the more likely you Examples: are to remember information. To remember that Homer wrote The Odyssey, just think, “Homer is an For example, to memorize a vocab word, odd name. formula, or equation, look at it, close your To remember that all 3 angles of an eyes, and try to see it in your mind. Then acute triangle must be less than 90˚, say it out loud and write it down. think “When you’re over 90, you’re not cute anymore.” Strategies… Create unforgettable images Create silly sentences Take the information you’re trying to Use the 1st letter of the words remember and create a crazy, you want to remember to make memorable picture in your mind. up a silly, ridiculous sentence. For example, to remember that the For example, to remember the explorer Pizarro conquered that Inca names of the 8 planets in order empire, imagine a pizza covering up an (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, ink spot. -

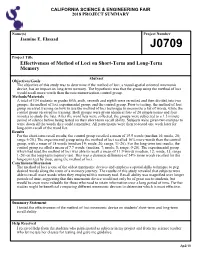

Effectiveness of Method of Loci on Short-Term and Long-Term Memory

CALIFORNIA SCIENCE & ENGINEERING FAIR 2018 PROJECT SUMMARY Name(s) Project Number Jasmine E. Elasaad J0709 Project Title Effectiveness of Method of Loci on Short-Term and Long-Term Memory Abstract Objectives/Goals The objective of this study was to determine if the method of loci, a visual-spatial oriented mnemonic device, has an impact on long-term memory. The hypothesis was that the group using the method of loci would recall more words than the rote memorization control group. Methods/Materials A total of 134 students in grades fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth were recruited and then divided into two groups: the method of loci experimental group; and the control group. Prior to testing, the method of loci group received training on how to use the method of loci technique to memorize a list of words, while the control group received no training. Both groups were given identical lists of 20 simple nouns and four minutes to study the lists. After the word lists were collected, the groups were subjected to a 1.5 minute period of silence before being tested on their short-term recall ability. Subjects were given two minutes to write down all the words they could remember. All participants were then re-tested one week later for long-term recall of the word list. Results For the short-term recall results, the control group recalled a mean of 15.5 words (median 16; mode, 20; range 6-20.) The experimental group using the method of loci recalled 16% more words than the control group, with a mean of 18 words (median 19; mode, 20; range, 11-20). -

Improving Memorization and Long Term Recall of System Assigned

IMPROVING MEMORIZATION AND LONG TERM RECALL OF SYSTEM ASSIGNED PASSWORDS By JAYESH DOOLANI Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPUTER SCIENCE THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON DECEMBER 2016 Copyright © by Jayesh Doolani 2016 All Rights Reserved ii To my family, friends and to my advisor, Dr. Matthew Wright, who guided me to where I am today. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervising professor Dr. Matthew Wright for his guidance, motivation and invaluable support throughout my graduate studies. He always guided me and gave constructive feedback about my work. It was a great learning experience for me under his guidance. I am grateful to Dr. Filia Makedon and to Dr. John Robb for taking time to serve on my thesis committee. I would specially like to mention the key role Dr. Fillia Makedon’s course on Human Computer Interaction played and was extremely beneficial for me in completing this thesis. I also want to thank Dr. Taiabul Haque for his key inputs and for providing great insights in this research area. I am also grateful to Dr. Feraydune Kashefi of Computer Science department who helped us recruit his class students for our user study. Last but not the least, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my parents who encouraged and motivated me to pursue my MS. This research would not have been possible without their emotional support. November 11, 2016 iv ABSTRACT IMPROVING MEMORIZATION AND LONG TERM RECALL OF SYSTEM ASSIGNED PASSWORDS Jayesh Doolani, M.S. -

Mnemonics 1 TITLE PAGE the Use of Melodic and Rhythmic

Mnemonics 1 TITLE PAGE The Use of Melodic and Rhythmic Mnemonics To Improve Memory and Recall in Elementary Students in the Content Areas Orla C. Hayes Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Education School of Education Dominican University of California San Rafael, CA May 2009 Mnemonics 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere thanks to Dr. Madalienne Peters for her expertise, time, accessibility and endless patience with me throughout this process. Many thanks to my supportive classmates for their positive input and ever-present words of encouragement. A special thank you to my brother Robert, who encouraged me to embark on this worthy endeavor and gently prodded me along the sometimes bumpy road. Thank you to Suzanne Roybal and all the knowledgeable librarians at Dominican University of California. To Gary, thank you for your unyielding love and support, financially, technologically and emotionally. And to my two boys, whose unbridled joy and laughter keeps me smiling every day, thank you. Mnemonics 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE...................................................................................................................................... 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................................................................................................... 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................... 3 ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... -

Developmental Trends in the Metamemory-Memory Behavior Relationship: an Lntegrative Review*

CHAPTER 3 Developmental Trends in the Metamemory-Memory Behavior Relationship: An lntegrative Review* Wolfgang Schneider lntroduction Since the beginning of the 1970s, increasing attention has been di rected toward the development of children's awareness of their own mem ory. This phenomenon has been termed metamemory by John Flavell (1971), who broadly defined it as the individual's potentially verbalizable knowledge concerning any aspect of inforrnation storage and retrieval. Whereas the interest in metamemory development has been growing rap idly since then, documenting the construct's general usefulness in a wide area of different memory situations, there are at least two critical points that deserve special consideration: (1) the conceptualization of the con struct and (2) its status as a predictor of actual memory behavior. While the latter is the topic of the present chapter and is discussed in more detail, we first concentrate on some problems related to the definition of meta memory. The first taxonomy of classes of memory knowledge was provided in the metamemoryinterview study by Kreutzer, Leonard, and Flavell (1975). •This manuscript was prepared during a stay at the Department of Psychology, Stan ford University, which was made possible by a grant from the Stiftung Volkswagenwerk, Hannover, Federal Republic of Germany. METACOGN!TIO , COGNIT IO , 57 Copyright © 1985 by Academic PTess AND HUMA PERFORMA CE All rights of reproduction in any form reserved. VOL. l ISBN 0-12-262301-0 58 Wolfgang Schneider Subsequently, Flavell and WeHman (1977) offered a more systematic and elaborated attempt to classify different types or contents of metamemory. Although alternative conceptualizations have been presented (see Chi, 1983), and more extended and general models of metacognition have been developed since (see FlaveH, 1978, 1979, 1981; Kluwe, 1982), the classifi cation scheme of FlaveH and WeHman has been used in the majority of empirical studies concerned with the development of metamemory. -

The Art of Memory and the Growth of the Scientific Method*

Interdisciplinary Description of Complex Systems 13(3), 373-396, 2015 THE ART OF MEMORY AND THE GROWTH OF THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD* Gopal P. Sarma** Emory University Atlanta, U.S.A. DOI: 10.7906/indecs.13.3.4 Received: 28 March 2015. Regular article Accepted: 23 June 2015. ABSTRACT I argue that European schools of thought on memory and memorization were critical in enabling growth of the scientific method. After giving a historical overview of the development of the memory arts from ancient Greece through 17th century Europe, I describe how the Baconian viewpoint on the scientific method was fundamentally part of a culture and a broader dialogue that conceived of memorization as a foundational methodology for structuring knowledge and for developing symbolic means for representing scientific concepts. The principal figures of this intense and rapidly evolving intellectual milieu included some of the leading thinkers traditionally associated with the scientific revolution; among others, Francis Bacon, Renes Descartes, and Gottfried Leibniz. I close by examining the acceleration of mathematical thought in light of the art of memory and its role in 17th century philosophy, and in particular, Leibniz’s project to develop a universal calculus. KEY WORDS scientific method, scientific revolution, the Enlightenment, methodological thinking, universal calculus CLASSIFICATION JEL: B19, O31 PACS: 01. *The title is adapted from Chapter 10 of Frances Yates’ book The Art of Memory. **Corresponding author, : [email protected]; +1 (404) 727-6123; **201 Dowman Drive, Atlanta, Georgia 30322 USA * G.P. Sarma INTRODUCTION “What is the scientific method?” It is a question that rarely makes an appearance in the scientific world. -

Close the Book. Recall. Write It Down. - Chronicle.Com

Print: Close the Book. Recall. Write It Down. - Chronicle.com http://chronicle.com/cgi-bin/printable.cgi?article=http://chronicl... http://chronicle.com/weekly/v55/i34/34a00101.htm From the issue dated May 1, 2009 Close the Book. Recall. Write It Down. That old study method still works, researchers say. So why don't professors preach it? By DAVID GLENN The scene: A rigorous intro-level survey course in biology, history, or economics. You're the instructor, and students are crowding the lectern, pleading for study advice for the midterm. If you're like many professors, you'll tell them something like this: Read carefully. Write down unfamiliar terms and look up their meanings. Make an outline. Reread each chapter. That's not terrible advice. But some scientists would say that you've left out the most important step: Put the book aside and hide your notes. Then recall everything you can. Write it down, or, if you're uninhibited, say it out loud. Two psychology journals have recently published papers showing that this strategy works, the latest findings from a decades-old body of research. When students study on their own, "active recall" — recitation, for instance, or flashcards and other self-quizzing — is the most effective way to inscribe something in long-term memory. Yet many college instructors are only dimly familiar with that research. And in March, when Mark A. McDaniel, a professor of psychology at Washington University in St. Louis and one author of the new studies, gave a talk at a conference of the National Center for Academic Transformation, people fretted that the approach was oriented toward robotic memorization, not true learning. -

Transference of Memory Strategies to Academic Learning and Memory

Transference of Memory Strategies to Academic Learning and Memory Sports Nicholas Solomon Ellis, Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders Faculty Sponsors Drs. Crystal Randolph, & Ruth Renee Hannibal Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders Abstract Methodology Results (continued) Memory is the process of recalling what has been learned and retained The participant is a college student who began to learn MTs in September memory techniques were higher for the memory games than especially through associative mechanisms. Anatomically, this includes 2015. The participant initially learned the MTs to learn Spanish vocabulary the academic assessment. electrical impulses fired in our brains to relay information. When we and then subsequently used the MTs to help learn course content. The learn new information, we use our memories to help recall the participant was given 2 tasks, one academic learning assessment and 2 Percentage of Responses Attributable to Memory information stored in our brains. Without memory, there is no access to Techniques memory sports games. The academic learning assessment was created by a 120 using stored information. Mnemonics are techniques used to improve professor in the participant’s major department and included 12 questions and enhance memory. Other memory techniques include but are not from content learned in courses taken Fall 2015. The questions were 100 s e s limited to, the method of loci, peg systems, and phonetic systems. n 80 developed based on Bloom’s taxonomy and were related to language o p s E From these systems spawned competitions, memory sports, which R development, phonetics, and general knowledge of CSD. Each section f o 60 e g have created remarkable feats of memorization.