Or, the Art of Picturesque Travel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My 214 Story Name: Christopher Taylor Membership Number: 3812 First Fell Climbed

My 214 Story Name: Christopher Taylor Membership number: 3812 First fell climbed: Coniston Old Man, 6 April 2003 Last fell climbed: Great End, 14 October 2019 I was a bit of a late-comer to the Lakes. My first visit was with my family when I was 15. We rented a cottage in Grange for a week at Easter. Despite my parents’ ambitious attempts to cajole my sister Cath and me up Scafell Pike and Helvellyn, the weather turned us back each time. I remember reaching Sty Head and the wind being so strong my Mum was blown over. My sister, 18 at the time, eventually just sat down in the middle of marshy ground somewhere below the Langdale Pikes and refused to walk any further. I didn’t return then until I was 28. It was my Dad’s 60th and we took a cottage in Coniston in April 2003. The Old Man of Coniston became my first summit, and I also managed to get up Helvellyn via Striding Edge with Cath and my brother-in-law Dave. Clambering along the edge and up on to the still snow-capped summit was thrilling. A love of the Lakes, and in particular reaching and walking on high ground, was finally born. Visits to the Lakes became more regular after that, but often only for a week a year as work and other commitments limited opportunities. A number of favourites established themselves: the Langdale Pikes; Lingmoor Fell; Catbells and Wansfell among them. I gradually became more ambitious in the peaks I was willing to take on. -

Complete 230 Fellranger Tick List A

THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS – PAGE 1 A-F CICERONE Fell name Height Volume Date completed Fell name Height Volume Date completed Allen Crags 784m/2572ft Borrowdale Brock Crags 561m/1841ft Mardale and the Far East Angletarn Pikes 567m/1860ft Mardale and the Far East Broom Fell 511m/1676ft Keswick and the North Ard Crags 581m/1906ft Buttermere Buckbarrow (Corney Fell) 549m/1801ft Coniston Armboth Fell 479m/1572ft Borrowdale Buckbarrow (Wast Water) 430m/1411ft Wasdale Arnison Crag 434m/1424ft Patterdale Calf Crag 537m/1762ft Langdale Arthur’s Pike 533m/1749ft Mardale and the Far East Carl Side 746m/2448ft Keswick and the North Bakestall 673m/2208ft Keswick and the North Carrock Fell 662m/2172ft Keswick and the North Bannerdale Crags 683m/2241ft Keswick and the North Castle Crag 290m/951ft Borrowdale Barf 468m/1535ft Keswick and the North Catbells 451m/1480ft Borrowdale Barrow 456m/1496ft Buttermere Catstycam 890m/2920ft Patterdale Base Brown 646m/2119ft Borrowdale Caudale Moor 764m/2507ft Mardale and the Far East Beda Fell 509m/1670ft Mardale and the Far East Causey Pike 637m/2090ft Buttermere Bell Crags 558m/1831ft Borrowdale Caw 529m/1736ft Coniston Binsey 447m/1467ft Keswick and the North Caw Fell 697m/2287ft Wasdale Birkhouse Moor 718m/2356ft Patterdale Clough Head 726m/2386ft Patterdale Birks 622m/2241ft Patterdale Cold Pike 701m/2300ft Langdale Black Combe 600m/1969ft Coniston Coniston Old Man 803m/2635ft Coniston Black Fell 323m/1060ft Coniston Crag Fell 523m/1716ft Wasdale Blake Fell 573m/1880ft Buttermere Crag Hill 839m/2753ft Buttermere -

Summits Lakeland

OUR PLANET OUR PLANET LAKELAND THE MARKS SUMMITS OF A GLACIER PHOTO Glacially scoured scenery on ridge between Grey Knotts and Brandreth. The mountain scenery Many hillwalkers and mountaineers are familiar The glacial scenery is a product of all these aries between the different lava flows, as well as the ridge east of Blea Rigg. However, if you PHOTO LEFT Solidi!ed lava "ows visible of Britain was carved with key features of glacial erosion such as deep phases occurring repeatedly and affecting the as the natural weaknesses within each lava flow, do have a copy of the BGS geology map, close across the ridge on High Rigg. out by glaciation in the U-shaped valleys, corries and the sharp arêtes that whole area, including the summits and high ridges. to create the hummocky landscape. Seen from the attention to what it reveals about the change from PHOTO RIGHT Peri glacial boulder!eld on often separate adjacent corries (and which provide Glacial ‘scouring’ by ice sheets and large glaciers summit of Great Rigg it is possible to discern the one rock formation to another as you trek along the summit plateau of Scafell Pike. not very distant past. some of the best scrambles in the Lakeland fells, are responsible for a typical Lakeland landscape pattern of lava flows running across the ridgeline. the ridge can help explain some of the larger Paul Gannon looks such as Striding Edge and Sharp Edge). of bumpy summit plateaus and blunt ridges. This Similar landscapes can be found throughout the features and height changes. -

RR 01 07 Lake District Report.Qxp

A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas Integrated Geoscience Surveys (North) Programme Research Report RR/01/07 NAVIGATION HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS DOCUMENT Bookmarks The main elements of the table of contents are bookmarked enabling direct links to be followed to the principal section headings and sub-headings, figures, plates and tables irrespective of which part of the document the user is viewing. In addition, the report contains links: from the principal section and subsection headings back to the contents page, from each reference to a figure, plate or table directly to the corresponding figure, plate or table, from each figure, plate or table caption to the first place that figure, plate or table is mentioned in the text and from each page number back to the contents page. RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY RESEARCH REPORT RR/01/07 A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the District and adjacent areas Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2004. D Millward Keywords Lake District, Lower Palaeozoic, Ordovician, Devonian, volcanic geology, intrusive rocks Front cover View over the Scafell Caldera. BGS Photo D4011. Bibliographical reference MILLWARD, D. 2004. A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas. British Geological Survey Research Report RR/01/07 54pp. -

Newsletter of the Yorkshire Branch of the Open University Geological Society March 2019

ON THE ROCKS Newsletter of the Yorkshire Branch of the Open University Geological Society March 2019 Langdale Pikes from Side Pike on Day 1 of Blencathra 2018. Harrison’s Sickle is the highest peak in the centre, with the brooding crags of Pavey Ark on the right. (Peter Vallely took the photo and his report starts on page 3). CONTENTS Rick’s Musings 1. Rick’s Musings 3. Blencathra 2018 Dear Members 7. Editor’s piece 8. 2019 AGM report Firstly, as this is the first newsletter of the year, let me say to all of you a belated 10. Baildon Hill walk 11. Committee members Happy New Year!! 12. Field trips 12. Mapping course Most of my article for this newsletter is based around a plea for your input, ideas, and opinions on a subject of great importance, and I would like as many of you to respond as possible. This year at our AGM, Ann resigned as Branch Treasurer after a term of office probably spanning two decades. Personally, I would like to say thank you to Ann for all her hard work over the years, Ann has been a mentor to me and most certainly one of my closest friends. As a Branch we have been lucky to have Ann as treasurer for so long, and she was treasurer for at least three Branch Organisers before me. The Yorkshire Branch of the OUGS March 2019 As a Branch we have one major problem. While we have found a temporary replacement for Ann, Jean Sampson has kindly agreed to stand in as treasurer but is only prepared to take on the role for one year, at next year’s AGM we will have to find a replacement. -

Southern Lake District Wainwright Bagging Holiday - the Southern Fells

Southern Lake District Wainwright Bagging Holiday - the Southern Fells Tour Style: Challenge Walks Destinations: Lake District & England Trip code: CNWAT Trip Walking Grade: 6 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW “All Lakeland is exquisitely beautiful, the Southern Fells just happen to be a bit of heaven fallen upon the earth” said Wainwright. The Southern Fells area of the Lake District is centred between the Langdale Valley to the north, Wastwater to the northwest, and Coniston village and Ambleside to the northeast, and includes England’s highest mountain, Scafell Pike. Within this area the fells are the highest and grandest in Lakeland, and make for a marvellous week of mountain walking. During the week we will ascend 28 of the 30 Wainwright Southern Fells which feature in Wainwright’s "A pictorial guide to the Lakeland fells, Book 4". As well as ascending the fells, the delightful valleys leading to them offer charming approaches and contrast to the rugged heights of the fells. WHAT'S INCLUDED • Great value: all prices include Full Board en-suite accommodation, a full programme of walks with all transport to and from the walks, and evening activities • Great walking: enjoy the challenge of bagging the summits in Wainwright’s Southern Fells Pictorial Guide, www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 accompanied by an experienced leader • Accommodation: enjoy comfortable en-suite rooms at the beautiful National Trust property, Monk Coniston, overlooking Coniston Water HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Follow in the footsteps of Alfred Wainwright exploring some of his favourite fells • Bag the summits in his Southern Fells Pictorial Guide • Enjoy challenging walking and a fantastic sense of achievement • Head out on guided walks to discover the varied beauty of the South Lakes on foot • Let our experienced leaders bring classic routes and hidden gems to life • After each walk enjoy fantastic accommodation at Monk Coniston which is beautifully located on the shores of Coniston Water; oozing history and all the home comforts needed after a day adventuring. -

Complete the Wainwright's in 36 Walks - the Check List Thirty-Six Circular Walks Covering All the Peaks in Alfred Wainwright's Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells

Complete the Wainwright's in 36 Walks - The Check List Thirty-six circular walks covering all the peaks in Alfred Wainwright's Pictorial Guides to the Lakeland Fells. This list is provided for those of you wishing to complete the Wainwright's in 36 walks. Simply tick off each mountain as completed when the task of climbing it has been accomplished. Mountain Book Walk Completed Arnison Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Birkhouse Moor The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Birks The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Catstye Cam The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Clough Head The Eastern Fells St John's Vale Skyline Dollywaggon Pike The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Dove Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Fairfield The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Glenridding Dodd The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Gowbarrow Fell The Eastern Fells Mell Fell Medley Great Dodd The Eastern Fells St John's Vale Skyline Great Mell Fell The Eastern Fells Mell Fell Medley Great Rigg The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Hart Crag The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Hart Side The Eastern Fells A Glenridding Circuit Hartsop Above How The Eastern Fells Kirkstone and Dovedale Circuit Helvellyn The Eastern Fells Greater Grisedale Horseshoe Heron Pike The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Mountain Book Walk Completed High Hartsop Dodd The Eastern Fells Kirkstone and Dovedale Circuit High Pike (Scandale) The Eastern Fells Greater Fairfield Horseshoe Little Hart Crag -

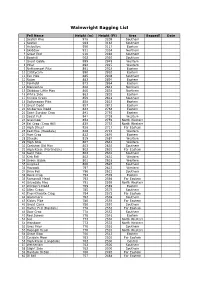

Wainwright Bagging List

Wainwright Bagging List Fell Name Height (m) Height (Ft) Area Bagged? Date 1 Scafell Pike 978 3209 Southern 2 Scafell 964 3163 Southern 3 Helvellyn 950 3117 Eastern 4 Skiddaw 931 3054 Northern 5 Great End 910 2986 Southern 6 Bowfell 902 2959 Southern 7 Great Gable 899 2949 Western 8 Pillar 892 2927 Western 9 Nethermost Pike 891 2923 Eastern 10 Catstycam 890 2920 Eastern 11 Esk Pike 885 2904 Southern 12 Raise 883 2897 Eastern 13 Fairfield 873 2864 Eastern 14 Blencathra 868 2848 Northern 15 Skiddaw Little Man 865 2838 Northern 16 White Side 863 2832 Eastern 17 Crinkle Crags 859 2818 Southern 18 Dollywagon Pike 858 2815 Eastern 19 Great Dodd 857 2812 Eastern 20 Stybarrow Dodd 843 2766 Eastern 21 Saint Sunday Crag 841 2759 Eastern 22 Scoat Fell 841 2759 Western 23 Grasmoor 852 2759 North Western 24 Eel Crag (Crag Hill) 839 2753 North Western 25 High Street 828 2717 Far Eastern 26 Red Pike (Wasdale) 826 2710 Western 27 Hart Crag 822 2697 Eastern 28 Steeple 819 2687 Western 29 High Stile 807 2648 Western 30 Coniston Old Man 803 2635 Southern 31 High Raise (Martindale) 802 2631 Far Eastern 32 Swirl How 802 2631 Southern 33 Kirk Fell 802 2631 Western 34 Green Gable 801 2628 Western 35 Lingmell 800 2625 Southern 36 Haycock 797 2615 Western 37 Brim Fell 796 2612 Southern 38 Dove Crag 792 2598 Eastern 39 Rampsgill Head 792 2598 Far Eastern 40 Grisedale Pike 791 2595 North Western 41 Watson's Dodd 789 2589 Eastern 42 Allen Crags 785 2575 Southern 43 Thornthwaite Crag 784 2572 Far Eastern 44 Glaramara 783 2569 Southern 45 Kidsty Pike 780 2559 Far -

Vivienne Crow Spends a Night Wild Camping Combining Some of the Best Day-Walks in the Lake District

Three Tarns with the Scafell group in the distance and Bowfell Links The up to the right LANGDALE ROUND Vivienne Crow spends a night wild camping combining some of the best day-walks in the Lake District. Photos: Vivienne Crow IT’S STILL DARK WHEN WE SET OFF FROM ELTERWATER. AUTUMN already has a hold on the woods, eerily silent in the calm, pre-dawn hour: where leaves had been hanging a week or so earlier, damp mist now clings to the melancholic branches, and the chill air holds just the faintest hint of decay. Wood smoke lingers in the air too, a sure sign that the Lake District summer is over. I’d recently been overwhelmed by the urge to beat the elements: to get in as many long hill days as possible before the storms come and the protracted nights make wild camping a much less attractive proposition. With the forecast promising a couple of fine days and almost windless nights, this seemed like the perfect time to complete a high-level circuit I’d been eyeing up for several years. The Langdale Round offered a chance to join together some of the best day walks I’d ever enjoyed in the National Park: Lingmoor Fell, Pike O’Blisco, Crinkle Crags, Bow Fell and, of course, the Pikes themselves. Just like old friends, each fell, each tarn, each ridge offers up its memories: moments of breathtaking beauty, of struggling along mist-bound, wind-battered ridges only to have the cloud suddenly part and reveal a glimpse of gnarled, craggy mountains; moments of fear, 30 THE GREAT OUTDooRS October 2013 CLASSIC ROUTE LANGDALE ROUND CriNklE CRAGS LOOMS SEDUctiVELY AT THE prEcipitOUS HEAD OF OVER THE CRINKLES OXENDALE. -

Winter Runs 2017/ 2018

Winter Runs 2017/ 2018. Please familiarise and prepare yourself for running in bad weather, darkness and possibly on your own. Be self reliant, just in case! Date Time First choice route Bad Weather Alternative Pub. Moon 18.10.17 1800 Scout Scar N/A. Riflemans. Full moon 16/10/16 25.10.17 1830 Loughrigg from A/side main car pk. Same as long run. Golden Rule A/side. Howgills start just along the road Full moon 04/11/17 01.11.17 1830 Fell Walls and around Winder Red Lion Sedbergh. from Peoples Hall, Sedbergh. 05:23am Run fromm Glenridding Youth Hostel 08.11.17 1830 Lakeland Trail 15km route T.B.C. route tbc on night. Harter Fell/ Kentmere Pike from 15.11.17 1830 Up to the col and return Castle P.H. Kendal. Longsleddale. 22.11.17 1830 Place Fell from Patterdale. Wansfell from Troutbeck. Watermill Ings. 29.11.2017 1830 Helvellyn from Wythburn Car Park. Reston Scar etc from Staveley. Watermill Ings. Full moon 03/12/17 06.12.17 1830 Red Screes from A/side main C.P. Loughrigg from A/side main car pk. Golden Rule. 03:47am Lingmoor Fell from Elterwater C.P. 13.12.17 1830 As main run. Britannia near pub A meal or Castle P.H. Xmas 20.12.17 1830 Scout Scar - last run before xmas. n/a. drink(s) TBC.????? 27.12.17 TBC Daytime run ? tbc tbc 03.01.18 1830 Steel Fell Round. Shortened version. Golden Rule. Thornthwaite Beacon from 10.01.18 1830 Wansfell from Troutbeck. -

The Boundary Committee for England Further Electoral

SHEET 3, MAP 3 South Lakeland District. Parish wards within Lakes Parish n r u B h Grisedale t y Tarn W Beck Raise n Pit h Bur Wyt (dis) P a s s o f D u n m a i l R a i s e Steel Fell Water R a i s e B e c k G ree THEn B BOUNDARY COMMITTEE FOR ENGLAND urn Bo ttom FURTHER ELECTORAL REVIEW OF SOUTH LAKELAND Draft Recommendations for Ward Boundaries in the District of South Lakeland November 2006 Sheet 3 of 10 G ree n B urn R a i s e B e c k A 5 9 1 "This map is reproduced from the OS map by The Electoral Commission with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. G re e n Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. B u Licence Number: GD03114G" rn Fa r E as ed al e G ill +++ R ive r R l o l th i ay G d a Scale : 1cm = 0.10000 km e h n e e r Grid interval 1km G F a r E Und a s e d a le LAKES GRASMERE PARISH WARD G eck il B l ve Groo KEY Rydal Fell DISTRICT BOUNDARY S D o EXISTINGu DISTRICT WARD BOUNDARY (TO BE RETAINED) rm R i lk EXISTING WARD G BOUNDARY (NO LONGER TO BE UTILISED) A i ll W PARISH BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH WARD BOUNDARY A H Easedale 5 Easedale 9 Tarn 1 PARISH WARD BOUNDARY COINCIDENT WITH WARD BOUNDARY S Tarn I PARISH WARD BOUNDARY R A LAKES AMBLESIDE & GRASMERE WARD PROPOSED WARD NAME P CONISTON WARD EXISTING WARD NAME (TO BE RETAINED) E D I LAKES CP PARISH NAME R y S d a l E PARISH WARD NAME B LAKES GRASMERE PARISH WARD e c L k B M A ill S G E as R e e E w da o le B iv h ec e in k r K r B R E N tle o A t t A i h L L 7 a -

Southern Lake District Wainwright Bagging Holiday - the Southern Fells

Southern Lake District Wainwright Bagging Holiday - the Southern Fells Tour Style: Challenge Walks Destinations: Lake District & England Trip code: CNWAT Trip Walking Grade: 6 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW “All Lakeland is exquisitely beautiful, the Southern Fells just happen to be a bit of heaven fallen upon the earth” said Wainwright. The Southern Fells area of the Lake District is centred between the Langdale Valley to the north, Wastwater to the northwest, and Coniston village and Ambleside to the northeast, and includes England’s highest mountain, Scafell Pike. Within this area the fells are the highest and grandest in Lakeland, and make for a marvellous week of mountain walking. During the week we will ascend 28 of the 30 Wainwright Southern Fells which feature in Wainwright’s "A pictorial guide to the Lakeland fells, Book 4". As well as ascending the fells, the delightful valleys leading to them offer charming approaches and contrast to the rugged heights of the fells. WHAT'S INCLUDED • Great value: all prices include Full Board en-suite accommodation, a full programme of walks with all transport to and from the walks, and evening activities • Great walking: enjoy the challenge of bagging the summits in Wainwright’s Southern Fells Pictorial Guide, www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 accompanied by an experienced leader • Accommodation: enjoy comfortable en-suite rooms at the beautiful National Trust property, Monk Coniston, overlooking Coniston Water HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Follow in the footsteps of Alfred Wainwright exploring some of his favourite fells • Bag the summits in his Southern Fells Pictorial Guide • Enjoy challenging walking and a fantastic sense of achievement • Head out on guided walks to discover the varied beauty of the South Lakes on foot • Let our experienced leaders bring classic routes and hidden gems to life • After each walk enjoy fantastic accommodation at Monk Coniston which is beautifully located on the shores of Coniston Water; oozing history and all the home comforts needed after a day adventuring.