1970-1971-Spring Quiz & Quill Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Notion of Song, Identities, Discourses, and Power

The Notion of Song, Identities, Discourses, and Power: Bridging Songs with Literary Texts to Enhance Students’ Interpretative Skills Elroy Alister Esdaille Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2020 Elroy Alister Esdaille All Rights Reserved Abstract Sometimes students struggle to interpret literary texts because some of these texts do not lend themselves to the deduction of the interpretative processes with which they are familiar, but the same is not true when students pull interpretations from songs. Is it possible that students’ familiarity with songs might enable them to connect a song with a book and aid interpretation that way? This study attempted to explore the possibility of bridging songs to literary texts in my Community College English classroom, to ascertain if or how the use of song can support or extend students’ interpretive strategies across different types of texts. I investigated how songs might work as a bridge to other texts, like novels, and, if the students use songs as texts, to what extent do the students develop and hone their interpretative skills? Because of this, how might including songs as texts in English writing or English Literature curriculum contribute to the enhancement of students’ writing? The students’ responses disclosed that the songs appealed to their cognition and memories and helped them to interpret and write about the novels they read. Moreover, the students’ responses revealed that pairing or matching songs with novels strengthened interpretation of the book in a plethora of ways, such as meta-message deduction, applying contexts, applying comparisons, and examining thematic correlations. -

Big Hits Karaoke Song Book

Big Hits Karaoke Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID 3OH!3 Angus & Julia Stone You're Gonna Love This BHK034-11 And The Boys BHK004-03 3OH!3 & Katy Perry Big Jet Plane BHKSFE02-07 Starstruck BHK001-08 Ariana Grande 3OH!3 & Kesha One Last Time BHK062-10 My First Kiss BHK010-01 Ariana Grande & Iggy Azalea 5 Seconds Of Summer Problem BHK053-02 Amnesia BHK055-06 Ariana Grande & Weeknd She Looks So Perfect BHK051-02 Love Me Harder BHK060-10 ABBA Ariana Grande & Zedd Waterloo BHKP001-04 Break Free BHK055-02 Absent Friends Armin Van Buuren I Don't Wanna Be With Nobody But You BHK000-02 This Is What It Feels Like BHK042-06 I Don't Wanna Be With Nobody But You BHKSFE01-02 Augie March AC-DC One Crowded Hour BHKSFE02-06 Long Way To The Top BHKP001-05 Avalanche City You Shook Me All Night Long BHPRC001-05 Love, Love, Love BHK018-13 Adam Lambert Avener Ghost Town BHK064-06 Fade Out Lines BHK060-09 If I Had You BHK010-04 Averil Lavinge Whataya Want From Me BHK007-06 Smile BHK018-03 Adele Avicii Hello BHK068-09 Addicted To You BHK049-06 Rolling In The Deep BHK018-07 Days, The BHK058-01 Rumour Has It BHK026-05 Hey Brother BHK047-06 Set Fire To The Rain BHK021-03 Nights, The BHK061-10 Skyfall BHK036-07 Waiting For Love BHK065-06 Someone Like You BHK017-09 Wake Me Up BHK044-02 Turning Tables BHK030-01 Avicii & Nicky Romero Afrojack & Eva Simons I Could Be The One BHK040-10 Take Over Control BHK016-08 Avril Lavigne Afrojack & Spree Wilson Alice (Underground) BHK006-04 Spark, The BHK049-11 Here's To Never Growing Up BHK042-09 -

Amici Curiae Brief of Erik Nielson, Charis E

No. 15-666 __________________________________________ In the Supreme Court of the United States _____ ____ TAYLOR BELL, Petitioner, V. ITAWAMBA COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, Respondent. _____ ____ On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court Of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ______ ___ AMICI CURIAE BRIEF OF ERIK NIELSON, CHARIS E. KUBRIN, TRAVIS L. GOSA, MICHAEL RENDER (AKA “KILLER MIKE”) AND OTHER SCHOLARS AND ARTISTS IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER _____ ____ CHARLES “CHAD” BARUCH Counsel of Record COYT RANDAL JOHNSTON JR. JOHNSTON TOBEY BARUCH 3308 Oak Grove Avenue Dallas, Texas 75204 (214) 741-6260 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae __________________________________________ LEGAL PRINTERS LLC, Washington DC ! 202-747-2400 ! legalprinters.com i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ........................................................ i Table of Authorities ................................................... ii Interests of Amici Curiae ........................................... 1 Summary of Argument .............................................. 3 Argument .................................................................... 6 A. “Fight the power”: The politics of hip hop .......... 6 B. “Put my Glock away, I got a stronger weapon that never runs out of ammunition”: The non- literal rhetoric of hip hop .................................. 12 C. “They ain’t scared of rap music—they scared of us”: Rap’s bad rap .............................................. 19 Conclusion ............................................................... -

May 2018 Be the Church. Everywhere, Every Day!

May 2018 Middle School Retreat a Be the church. Everywhere, every day! every Everywhere, Be the church. huge success. See what else they’re up to on pg 23. TABLE OF CONTENTS Contributors: Creative Director .................Kirk Rhodes Senior Graphic Designer ...... Dede Caruso Attend the Editors ....................... Melissa Bogdany When Helping Hurts Nancy Doran Mary Trier two-day seminar. Carol Harris Writers ........................... Greg Robson Bob Castaldi Page 4 Jeremy Jobson Rebecca Lang Matt Shiles Monica Smith Pam Anderson Plan for your future Javier G. Velasquez Photographers .................... Fe Salviano at the free estate Kirk Rhodes Bradley Nolff planning seminar. Jessica Saphirstein David Saphirstein Page 6 Shaun Trout John Pierce, Jr. John Kuhn gettyimages.com Printer ....... Central Florida Publishing, Inc. Read about the impact Send newspaper correspondence to: [email protected]. Northlanders have around the globe. Our Purpose: Why we are here. Pages 9-12 From its inception in 1972, Northland has been unwavering in its purpose: To bring people to maturity in Christ. Our Vision: What we see. A vision is a clear mental picture of a preferable future. It sees the future through the eyes of faith. It shares the perspective of the biblical writer when he wrote the following words: “Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, Go behind the scenes the conviction of things not seen” (Hebrews 11:1, NASB). Northland’s vision is to see people coming to Christ, and to be transformed together as we link locally and globally to with worship leader, worship and serve everywhere, every day. Kailey Simpson. Our Mission: What we do. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Echo and Pine

Get Your Kicks at the 50th June 2-5, 2016 Echo and Pine 1 Letter from the President Dear Members of the Classes of 1966: On this noteworthy anniversary, it is my great pleasure to welcome you, the trailblazing members of the Classes of 1966, back to campus. From my conversations with many of you and from the memories you share in the following pages, it is apparent that the social and political upheavals of the mid-1960s – and their expressions on campus – substantially shaped your worldviews and your lives. Equally apparent is the collective sense of the Colleges’ impact on the way in which your Classes navigated those turbulent times, from the attentiveness and care of the faculty and administration, to the camaraderie of the student body, to the thought-provoking nature of the coursework. As we join together in celebrating with you this Golden Jubilee, perhaps most apparent is the remarkable success of the Classes of 1966, not only in spite of the changing national landscape 50 years ago, but also because of it. Through the burgeoning Civil Rights movement and the Vietnam War, through the Cold War and the advent of the Internet, through the 9/11 attacks and increasing globalization, your classes have thrived in this changing world and helped shape it – as doctors and educators; business and religious leaders; attorneys and musicians; service-members in law enforcement and the military; Fulbright winners and world-travelers; local, national and international volunteers; and parents and grandparents. On behalf of our faculty, staff and students, I thank you for joining us this weekend and for your indelible contributions to your communities, your country and your alma maters. -

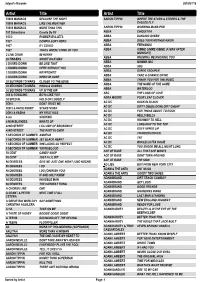

Tricerasoft Song Book Creator

Jolyon's Karaoke 2018/07/18 ArtistTitle Artist Title 10000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT AARON TIPPIN WHERE THE STARS & STRIPES & THE 10000 MANIACS LIKE THE WEATHER EAGLES FLY 10000 MANIACS MORE THAN THIS AARON TIPPIN WORKING MANS PHD 101 Dalmations Cruella De Vil ABBA CHIQUITITA 10CC RUBBER BULLETS ABBA DANCING QUEEN 1927 COMPULSORY HERO ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW 1927 IF I COULD ABBA FERNANDO 1927 THATS WHEN I THINK OF YOU ABBA GIMME GIMME GIMME (A MAN AFTER MIDNIGHT) 2 LIVE CREW IM HORNY ABBA KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN ABBA MAMMA MIA 3 DOORS DOWN BE LIKE THAT ABBA SOS 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU ABBA SUPER TROUPER 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE ABBA TAKE A CHANCE ON ME 3 DOORS DOWN WHEN IM GONE ABBA THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC 30 SECONDS TO MARS CLOSER TO THE EDGE ABBA THE NAME OF THE GAME 30 SECONDS TO MARS KINGS & QUEENS ABBA WATERLOO 30 SECONDS TO MARS UP IN THE AIR ABC THE LOOK OF LOVE 360 & GOSSLING BOYS LIKE YOU ABRA MOORE FOUR LEAF CLOVER 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY AC DC BACK IN BLACK 3OH3 DONT TRUST ME AC DC DIRTY DEEDS DONE DIRT CHEAP 3OH3 & KATIE PERRY STARSTRUKK AC DC FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK 3OH3 & KESHA MY FIRST KISS AC DC HELLS BELLS 4 am SUKIYAKI AC DC HIGHWAY TO HELL 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP AC DC LONG WAY TO THE TOP 42ND STREET LULLABY OF BROADWAY AC DC STIFF UPPER LIP 42ND STREET THE PARTYS OVER AC DC THUNDERSTRUCK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA AC DC TNT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER JET BLACK HEART AC DC WHOLE LOTTA ROSIE 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT AC DC YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER YOUNGBLOOD -

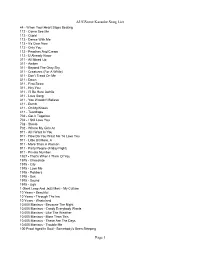

Augsome Karaoke Song List Page 1

AUGSome Karaoke Song List 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 112 - Come See Me 112 - Cupid 112 - Dance With Me 112 - It's Over Now 112 - Only You 112 - Peaches And Cream 112 - U Already Know 311 - All Mixed Up 311 - Amber 311 - Beyond The Gray Sky 311 - Creatures (For A While) 311 - Don't Tread On Me 311 - Down 311 - First Straw 311 - Hey You 311 - I'll Be Here Awhile 311 - Love Song 311 - You Wouldn't Believe 411 - Dumb 411 - On My Knees 411 - Teardrops 702 - Get It Together 702 - I Still Love You 702 - Steelo 702 - Where My Girls At 911 - All I Want Is You 911 - How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 - Little Bit More, A 911 - More Than A Woman 911 - Party People (Friday Night) 911 - Private Number 1927 - That's When I Think Of You 1975 - Chocolate 1975 - City 1975 - Love Me 1975 - Robbers 1975 - Sex 1975 - Sound 1975 - Ugh 1 Giant Leap And Jazz Maxi - My Culture 10 Years - Beautiful 10 Years - Through The Iris 10 Years - Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs - Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs - Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs - Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This 10,000 Maniacs - These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs - Trouble Me 100 Proof Aged In Soul - Somebody's Been Sleeping Page 1 AUGSome Karaoke Song List 101 Dalmations - Cruella de Vil 10Cc - Donna 10Cc - Dreadlock Holiday 10Cc - I'm Mandy 10Cc - I'm Not In Love 10Cc - Rubber Bullets 10Cc - Things We Do For Love, The 10Cc - Wall Street Shuffle 112 And Ludacris - Hot And Wet 12 Gauge - Dunkie Butt 12 Stones - Crash 12 Stones - We Are One 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Audiojuke Music List 11/12

Cliffhangers DIGITAL JUKEBOX Song list www.cliffhangers.com.au All 3000+ songs are included with our Digital Jukeboxes. For Karaoke songs on our jukeboxes please download our Karaoke song list. These are available in addition to the normal AUDIO ONLY tracks below. PH: (07) 55 942 900 Red is 50s&60s tracks, Yellow is 70s tracks, Blue is 80s tracks ..this will help you ( ) 10CC - DREADLOCK HOLIDAY ( ) Agnes – I NEED YOU NOW(RADIO EDIT) ( ) 112 - DANCE WITH ME ( ) Agnes – RELEASE ME ( ) 2 PAC – CALIFORNIA LOVE ( ) Aguilera/Pink/Mya - LADY MARMALADE ( ) 2 PAC – CHANGES ( ) Air – LA FEMME DARGENT ( ) 2 Pac – GHETTO GOSPEL ( ) Akon - ANGEL ( ) 28 Days - RIP IT UP ( ) Akon ft Colby O'Donis & Kardinal Offishall - BEAUTIFUL ( ) 28 Days - SAY WHAT ( ) Akon – DON'T MATTER ( ) 3oh!3 – DON'T TRUST ME ( ) Akon – SORRY, BLAME IT ON ME ( ) 3oh!3 – DOUBLE VISION ( ) Akon – LONELY ( ) 3OH!3 – STARSTRUKK ( ) Akon feat Eminem – SMACK THAT ( ) 3OH!3 feat Ke$ha – MY FIRST KISS ( ) Akon ft Keri Hilson – OH AFRICA ( ) 360FT Gossing – BOYS L;IKE YOU (clean) ( ) Akon feat Snoop Dogg – I WANNA LOVE YOU ( ) 30 Seconds to Mars-CLOSER TO THE EDGE ( ) Alan Jackson - DON’T ROCK THE JUKEBOX ( ) 30 Seconds to Mars – THE KILL (BURY ME) ( ) Alanis Morrisette - HAND IN MY POCKET ( ) 3 Doors Down – IT'S NOT MY TIME ( ) Alanis Morrisette - HANDS CLEAN ( ) 3 Doors Down – HERE WITHOUT YOU ( ) Alanis Morrisette – IRONIC ( ) 3 Doors Down – KYPTONITE ( ) Alcazar - CRYING AT THE DISCOTEQUE ( ) 3LW - NO MORE (BABY IMA DO U RITE) ( ) Alesha Dixon – THE BOY DOES NOTHING ( ) 4 Non Blondes -

Regulated Child Care Programs in Senate District 1, Lawrence M

Regulated Child Care Programs in Senate District 1, Lawrence M. Farnese (D) Total Regulated Child Care Programs: 174 Total Pre‐K Counts: 2 Total Head Start Supplemental: 5 Star 4: 13 Star 3: 19 Star 2: 13 Star 1: 114 No Star Level: 8 Keystone Star Head Start Program Name Address City Zip Level Pre‐K Counts Supplemental Bright Horizons Child Care and Learning Center 401 N 21ST ST PHILADELPHIA 19130 STAR 4‐ Acc No No CHILDRENS VILLAGE INC 125 N 8TH ST PHILADELPHIA 19106 STAR 4‐ Acc No Yes COM COLLEGE OF PHILA CHILD DEV CENTER 540 N 16TH ST PHILADELPHIA 19130 STAR 4‐ Acc No No JEFFERSON CHILD CARE CENTER 912 WALNUT ST # 28 PHILADELPHIA 19107 STAR 4‐ Acc No No NORRIS SQUARE CHILDRENS CENTER 2011 N MASCHER ST PHILADELPHIA 19122 STAR 4‐ Acc No No SETTLEMENT MUSIC SCHOOL 416 QUEEN ST PHILADELPHIA 19147 STAR 4‐ Acc No Yes WESTERN COMMUNITY CENTER 1613 SOUTH ST # 21 PHILADELPHIA 19146 STAR 4‐ Acc No Yes ARCH STREET PRESCHOOL 1724 ARCH ST PHILADELPHIA 19103 STAR 4 No No BEE NEES BABIES EDUCATIONAL LRNG CTR 803 N 15TH ST PHILADELPHIA 19130 STAR 4 No No CANAAN LAND FAMILY CHILD CARE 1007 S 18TH ST PHILADELPHIA 19146 STAR 4 No No CHINATOWN LEARNING CENTER 1034 SPRING ST PHILADELPHIA 19107 STAR 4 No Yes COOKIES DAY CARE CENTER 2135 S 17TH ST PHILADELPHIA 19145 STAR 4 No No EARLY CHILDHOOD ENVIRONMENTS LLC 762 S BROAD ST PHILADELPHIA 19146 STAR 4 No No FRANKLIN DAY NURSERY 719 JACKSON ST PHILADELPHIA 19148 STAR 4 No No KEN‐CREST SERVICES‐SOUTH CENTER 504 MORRIS ST PHILADELPHIA 19148 STAR 4 No No KINDERCARE LEARNING CENTER 303009 1700 MARKET ST PHILADELPHIA -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Crush Garbage 1990 (French) Leloup (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue 1994 Jason Aldean (Ghost) Riders In The Sky The Outlaws 1999 Prince (I Called Her) Tennessee Tim Dugger 1999 Prince And Revolution (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole 1999 Wilkinsons (If You're Not In It For Shania Twain 2 Become 1 The Spice Girls Love) I'm Outta Here 2 Faced Louise (It's Been You) Right Down Gerry Rafferty 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue The Line 2 On (Explicit) Tinashe And Schoolboy Q (Sitting On The) Dock Of Otis Redding 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc The Bay 20 Years And Two Lee Ann Womack (You're Love Has Lifted Rita Coolidge Husbands Ago Me) Higher 2000 Man Kiss 07 Nov Beyonce 21 Guns Green Day 1 2 3 4 Plain White T's 21 Questions 50 Cent And Nate Dogg 1 2 3 O Leary Des O' Connor 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 1 2 Step Ciara And Missy Elliott 21st Century Girl Willow Smith 1 2 Step Remix Force Md's 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 1 Thing Amerie 22 Lily Allen 1, 2 Step Ciara 22 Taylor Swift 1, 2, 3, 4 Feist 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 22 Steps Damien Leith 10 Million People Example 23 Mike Will Made-It, Miley 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan Cyrus, Wiz Khalifa And 100 Years Five For Fighting Juicy J 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis And The News 24 Jem 100% Cowboy Jason Meadows 24 Hour Party People Happy Mondays 1000 Stars Natalie Bassingthwaighte 24 Hours At A Time The Marshall Tucker Band 10000 Nights Alphabeat 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan 24 Hours From You Next Of Kin 1-2-3 Len Berry 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 1234 Sumptin' New Coolio 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins 25 Miles Edwin Starr 15 Minutes Of Shame Kristy Lee Cook 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 18 And Life Skid Row 29 Nights Danni Leigh 18 Days Saving Abel 3 Britney Spears 18 Til I Die Bryan Adams 3 A.M. -

“Don't Believe the Hype”: the Polemics of Hip Hop and The

ABSTRACT Title of Document: “DON’T BELIEVE THE HYPE”: THE POLEMICS OF HIP HOP AND THE POETICS OF RESISTANCE AND RESILIENCE IN BLACK GIRLHOOD. Chyann L. Oliver, PhD, 2009 Directed By: Associate Professor, Sheri L. Parks, Department of American Studies At a time when Hip Hop is mired in masculinity, and scholars are “struggling for the soul of this movement” through excavating legacies in a black nationalist past, black girls and women continue to be bombarded with incessant, one-dimensional, images of black women who are reduced solely to sum of their sexual parts. Without the presence of a counter narrative on black womanhood and femininity in Hip Hop, black girls who are growing up encountering Hip Hop are left to define and negotiate their identities as emerging black women within a sexualized context. This dissertation asks: how can black girls, and more specifically, working class black girls, who are faced with inequities because of their race, class, and gender find new ways to define themselves, and name their experiences, in their own words and on their own terms? How can black girls develop ways of being resistant and resilient in the face of adversity, and in the midst of this Hip Hop “attack on black womanhood?” Using myriad forms of writing and fusing genres of critical essay, poetry, prose, ethnography, and life history, this dissertation, as a feminist, artistic, cultural, and political Hip Hop intervention, seeks to address the aforementioned issues by demonstrating the importance of black women’s vocality in Hip Hop. It examines how black women in Hip Hop have negotiated race, class, gender, and sexuality from 1979 to the present.