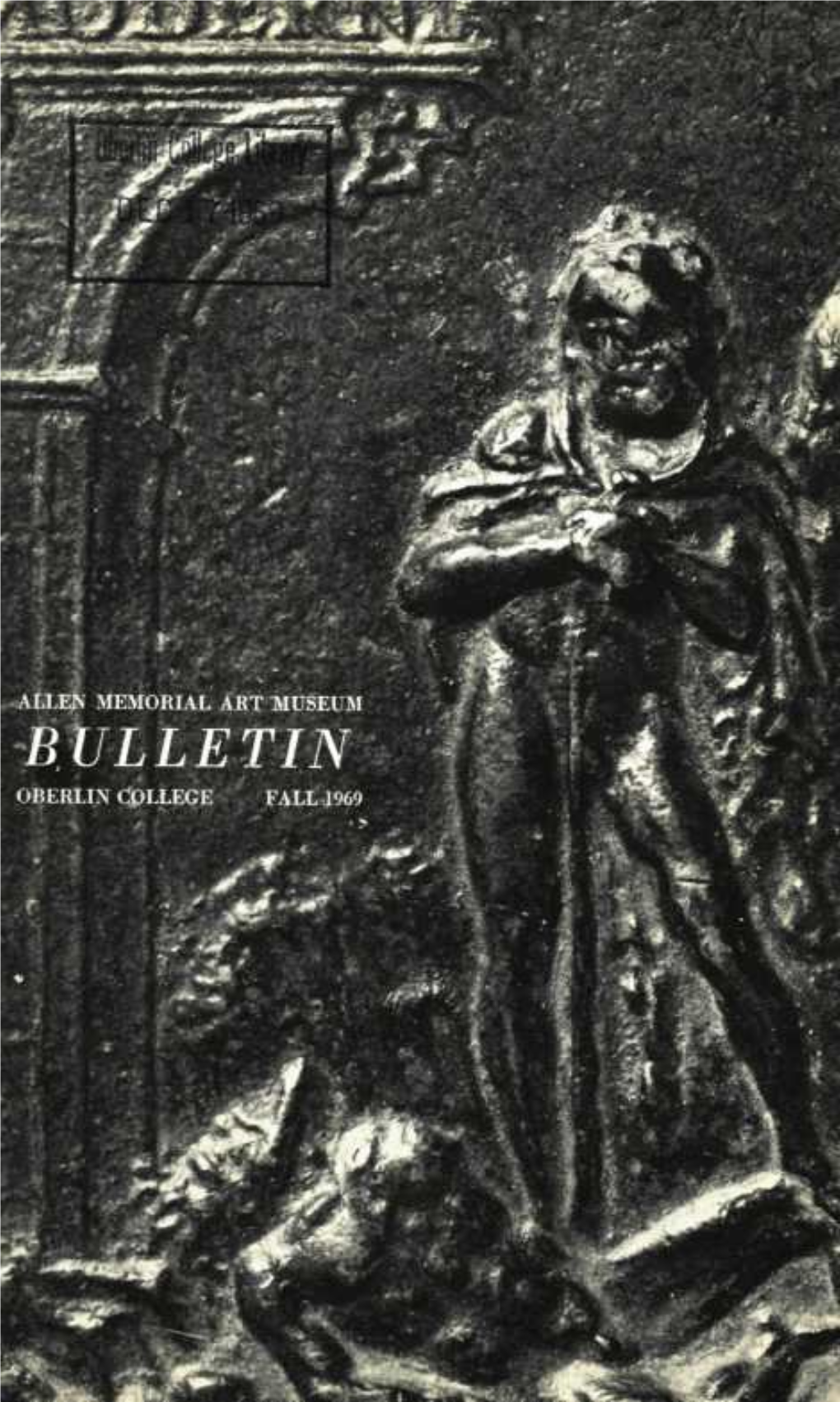

BULLETIN OBERLIN Cjpllege FALL 1969

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe Before 1850 Gallery 15

Art from the Ancient Mediterranean and Europe before 1850 Gallery 15 QUESTIONS? Contact us at [email protected] ACKLAND ART MUSEUM The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 101 S. Columbia Street Chapel Hill, NC 27514 Phone: 919-966-5736 MUSEUM HOURS Wed - Sat 10 a.m. - 5 p.m. Sun 1 - 5 p.m. Closed Mondays & Tuesdays. Closed July 4th, Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, & New Year’s Day. 1 Domenichino Italian, 1581 – 1641 Landscape with Fishermen, Hunters, and Washerwomen, c. 1604 oil on canvas Ackland Fund, 66.18.1 About the Art • Italian art criticism of this period describes the concept of “variety,” in which paintings include multiple kinds of everything. Here we see people of all ages, nude and clothed, performing varied activities in numerous poses, all in a setting that includes different bodies of water, types of architecture, land forms, and animals. • Wealthy Roman patrons liked landscapes like this one, combining natural and human-made elements in an orderly structure. Rather than emphasizing the vast distance between foreground and horizon with a sweeping view, Domenichino placed boundaries between the foreground (the shoreline), middle ground (architecture), and distance. Viewers can then experience the scene’s depth in a more measured way. • For many years, scholars thought this was a copy of a painting by Domenichino, but recently it has been argued that it is an original. The argument is based on careful comparison of many of the picture’s stylistic characteristics, and on the presence of so many figures in complex poses. At this point in Domenichino’s career he wanted more commissions for narrative scenes and knew he needed to demonstrate his skill in depicting human action. -

Mist: an Analytical Study Focusing on the Theme and Imagery of the Novel

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY– SEPT 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 Mist: An Analytical Study Focusing on the Theme and Imagery of the Novel *Arya V. Unnithan Guest Lecturer, NSS College for Women, Karamana, Trivandrum, Kerala Received: May 23, 2018 Accepted: June 30, 2018 ABSTRACT Mist, the Malayalam novel is certainly a golden feather in M.T. Vasudevan Nair’s crown and is a brilliant work which has enhanced Malayalam literature’s fame across the world. This novel is truly different from M.T.’s other writings such as Randamuzham or its English translation titled Bhima. M.T. is a writer with wonderfulnarrative skills. In the novel, he combined his story- telling power with the technique of stream- of- consciousness and thereby provides readers, a brilliant reading experience. This paper attempts to analyse the novel, with special focus on its theme and imagery, thereby to point out how far the imagery and symbolism agrees with the theme of the novel. Keywords: analysis-theme-imagery-Vimala-theme of waiting- love and longing- death-stillness Introduction: Madath Thekkepaattu Vasudevan Nair, popularly known as M.T., is an Indian writer, screenplay writer and film director from the state of Kerala. He is a creative and gifted writer in modern Malayalam literature and is one of the masters of post-Independence Indian literature. He was born on 9 August 1933 in Kudallur, a village in the present day Pattambi Taluk in Palakkad district. He rose to fame at the age of 20, when he won the prize for the best short story in Malayalam at World Short Story Competition conducted by the New York Herald Tribune. -

Busman's Honeymoon

Busman's Honeymoon By Dorothy L. Sayers Busman's Honeymoon CHAPTER I NEW-WEDDED LORD I agree with Dryden, that "Marriage is a noble daring"— samuel johnson: Table Talk. Mr. Mervyn Bunter, patiently seated in the Daimler on the far side of Regent's Park, reflected that time was getting on. Packed in eiderdowns in the back of the car was a case containing two and a half dozen of vintage port, and he was anxious about it. Great speed would render the wine undrinkable for a fortnight; excessive speed would render it undrinkable for six months. He was anxious about the arrangements—or the lack of them—at Talboys. He hoped everything would be found in good order when they arrived—otherwise, his lady and gentleman might get nothing to eat till goodness knew when. True, he had brought ample supplies from Fortnum's, but suppose there were no knives or forks or plates available? He wished he could have gone ahead, as originally instructed, to see to things. Not but what his lordship was always ready to put up with what couldn't be helped; but it was unsuitable that his lordship should be called on to put up with anything—besides, the lady was still, to some extent, an unknown factor. What his lordship had had to put up with from herduring the past five or six years, only his lordship knew, but Mr. Bunter could guess. True, the lady seemed now to be in a very satisfactory way of amendment; but it was yet to be ascertained what her conduct would be under the strain of trivial inconvenience. -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

The Dutch School of Painting

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924073798336 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 924 073 798 336 THE FINE-ART LIBRARY. EDITED BY JOHN C. L. SPARKES, Principal of the National Art Training School, South Kensington - Museum, THE Dutch School Painting. ye rl ENRY HA YARD. TRANSLATED HV G. POWELL. CASSELL & COMPANY, Limited: LONDON, PARIS, NEW YORK ,C- MELBOURNE. 1885. CONTENTS. -•o*— ClIAr. I'AGE I. Dutch Painting : Its Origin and Character . i II. The First Period i8 III. The Period of Transition 41 IV. The Grand Ki'ocii 61 V. Historical and Portrait Painters ... 68 VI. Painters of Genre, Interiors, Conversations, Societies, and Popular and Rustic Scenes . 117 VI [. Landscape Painters 190 VIII. Marine Painters 249 IX. Painters of Still Life 259 X. The Decline ... 274 The Dutch School of Painting. CHAPTER I. DUTCH PAINTING : ITS ORIGIN AND CHARACTER. The artistic energy of a great nation is not a mere accident, of which we can neither determine the cause nor foresee the result. It is, on the contrary, the resultant of the genius and character of the people ; the reflection of the social conditions under which it was called into being ; and the product of the civilisation to which it owes its birth. All the force and activity of a race appear to be concentrated in its Art ; enterprise aids its growth ; appreciation ensures its development ; and as Art is always grandest when national prosperity is at its height, so it is pre-eminently by its Art that we can estimate the capabilities of a people. -

Masters of Mobility Cultural Exchange Between the Netherlands and Germany in the Long 17Th Century

Masters of Mobility Cultural Exchange between the Netherlands and Germany in the Long 17th Century 8-9 October 2017: International two-day symposium on the occasion of the 75th anniversary of Horst Gerson’s publication Ausbreitung und Nachwirkung der holländischen Malerei des 17. Jahrhunderts Sunday 8 October, 2017: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam 09.00 - 09.30 Registration and Coffee INTRODUCTION 09.30 - 09.35 Taco Dibbits, Welcome 09.35 - 09.45 Gregor Weber, Introduction 09.45 - 10.05 Rieke van Leeuwen, Presentation of Gerson Digital: Germany and Visualization of 'Masters of Mobility' 10.05 - 10.25 Th. DaCosta Kaufmann, Gerson's Ausbreitung and its Meaning for the Study of Netherlandish Art in the International Context 10.25 - 10.45 Johannes Müller, Later-generation Migrants and their Impact on Cultural Transfer between Germany and the Low Countries 10.45 - 11.00 Discussion 11.00 -11.25 Coffee NETWORKS OF NETHERLANDISH-GERMAN CULTURAL EXCHANGE 11.25 - 11.30 Chair, Introduction to Section 11.30 - 11.50 Katharina Schmidt-Loske and Kurt Wettengl, Flemish Artists in Frankfurt around 1600 11.50 - 12.10 Amanda Herrin, Working Together - Apart: Collaborative Printmaking across Religious Conflict 12.10 - 12.30 Berit Wagner, The Art Dealer Family of Caymox, as Mediators of Flemish Artworks around 1600 12.30 - 12.40 Discussion 12.40 - 13.45 Lunch COURT ARTISTS FROM THE LOW COUNTRIES IN GERMANY 13.45 - 13.50 Chair, Introduction to Section 13.50 - 14.10 Marten Jan Bok, Court Artists from the Low Countries in Germany 14.10 - 14.30 Gero Seelig, Dutch and Flemish artists in Mecklenburg in the 16th and 17th centuries 14.30 - 14.50 Frits Scholten, The Legacy of Johan Gregor van der Schardt in Nuremberg 14.50 - 15.10 Gabri van Tussenbroek, Dutch Architects, Engineers and Entrepreneurs in Berlin and Brandenburg (1648-1688) 15.10 - 15.20 Discussion 15.20 - 15.40 Tea 15.40 - 16.00 Anna Koldeweij, German Relations of the Still-life Painter Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750). -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka 3930424 March 2018 Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context University of Utrecht Prof. dr. M.A. Weststeijn Prof. dr. E. Manikowska 1 Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Index Introduction p. 4 Historiography and research motivation p. 4 Theoretical framework p. 12 Research question p. 15 Chapters summary and methodology p. 15 1. The collection of Stanisław August 1.1. Introduction p. 18 1.1.1. Catalogues p. 19 1.1.2. Residences p. 22 1.2. Netherlandish painting in the collection in general p. 26 1.2.1. General remarks p. 26 1.2.2. Genres p. 28 1.2.3. Netherlandish painting in the collection per stylistic schools p. 30 1.2.3.1. The circle of Rubens and Van Dyck p. 30 1.2.3.2. The circle of Rembrandt p. 33 1.2.3.3. Italianate landscapists p. 41 1.2.3.4. Fijnschilders p. 44 1.2.3.5. Other Netherlandish artists p. 47 1.3. Other painting schools in the collection p. 52 1.3.1. Paintings by court painters in Warsaw p. 52 1.3.2. Italian paintings p. 53 1.3.3. French paintings p. 54 1.3.4. German paintings p. -

AAUW Pendleton Branch Newsletter February 2015

AAUW Pendleton Branch Newsletter February 2015 AAAAUUWW PPeennddlleettoonn BBrraanncchh FFeebbrruuaarryy MMeemmbbeerrsshhiipp MMeeeettiinngg Program: History Film Projects, by Griswold High School Students, Helix February 7 (Saturday) 11:00 a.m. Prodigal Son Hostesses: Harriet Isom and Gail Plute March Meeting Saturday, March 7, 11:00 a.m., Prodigal Son “Travel in Cuba” by Sharon Vincent and Melissa Woodbury 1 2014–2015 Pendleton Branch AAUW Leadership Team: NOTES & ANNOUNCEMENTS 541- Co-Presidents February Lunch Bunch: The February Lunch Bunch will be Karen King 278-2151 Thursday, February 19, at 11:45 a.m., at Eden’s Kitchen (on SW Melissa Woodbury 276-0268 6th Street, across from the Library/City Hall). Communications Vice President February Board Meeting: Renee Struthers will host the February Marlene Krout 276-7596 board meeting on Thursday, February 19, 7:00 p.m., at Melissa Membership Vice-President Woodbury’s home. Jan Bruning 276-1929 Finance Vice-President Dianne Barnes 276-5547 Co-Program Vice-Presidents Renée Struthers 377-0504 Sharon Vincent 278-1397 February Membership Recording Secretary Meeting Program Judy Witte 276-6289 Appointed Leaders: Two interesting documentary projects by Griswold High School students from Helix BMCC Liaison TBD EF/LAF Kathleen Mace 276-1006 Newsletter & Directory Editor Alexis Keene and Morgan Warner Susan Doyle 966-8854 A documentary Bylaws on the hardships faced by soldiers returning Kathy Ward 276-0308 from Vietnam AAUW Association website aauw.org AAUW of Oregon website Braden Sprenger and Jason Bushman aauw-or.aauw.net A documentary on the discrimination faced by Japanese AAUW Pendleton website Americans when they returned to Hood River pendleton-or.aauw.net after being interned or serving in the military Guests are Welcome! 2 President’s Corner for February 2015 Karen King and Melissa Woodbury Those of you who were able to attend the January meeting at the Prodigal Son know what interesting presentations on STEM Programs were given by Josh Ego and Patricia Dawson. -

Challenge the Good News Paper

TM THE GOOD NEWS PAPER No. 437 au.challenge.news SAVED FROM AN Spencer Nicholls EARLY GRAVE and his family. ooking at Spencer Nicholls walked right off the pier into the today, a happily married father freezing water. of three and a board member He would have drowned if not for of a successful addiction recov- the fact that he suddenly saw ‘an Lery centre in Western Australia, it’s unbelievably bright light’ that led almost impossible to imagine him him to shore. at 17, unconscious on the fl oor of a A few years later, he was a pas- public toilet foaming at the mouth senger in a stolen car being driven and close to death after yet another by a friend who was high from sniff - heroin overdose. ing petrol. The blonde 45-year-old is boyish Travelling at more than 100kmh and irrepressibly joyful. He is an in the middle of winter, the car shot absolute Duracell bunny of a man around a corner, skidded, spun on when he speaks to crowds about the icy road, clipped another vehicle his work, hopping and bouncing on and flipped, catapulting Spencer stage like he has hidden springs in through the windscreen, into the air his shoes. and head fi rst into a fi eld turned to Yet 30 years ago that is exactly rock by ice. where Spencer was – passed out Spencer blacked out. When he on the fi lthy fl oor of a public toi- opened his eyes, the first thing let. Hopelessly addicted to heroin, he realised was that his head was cocaine, alcohol and promiscuity by underground. -

Library Inventory Arch Book Series Book Title No Of

LIBRARY INVENTORY ARCH BOOK SERIES BOOK TITLE NO OF COPIES Adam’s Story 13 Daniel and the Lions Den 1 Elijah and the Wicked Queen 14 Events of the Bible 17 Samson’s Secret 1 The Angry King 13 The Boy Who Gave His Lunch Away 1 The Boy Who Was Lost 1 The Boy With A Sling 13 The Bread and the Wine – The Story of the Last Supper 2 The Coming of the Holy Spirit 1 The Fishermen’s Surprise 1 The Good Samaritan 2 The Great Escape 11 The Great Surprise 2 The House on the Rock 1 The Lame Man Who Walked Again 2 The Man Caught by A Fish 14 The Secret of the Star – The Story of the Wise Men 1 The Story of Noah’s Ark 11 The Story of Zerubbabel 15 The Temple King Solomon Built 13 The Walls Came Tumbling Down 15 The Water That Caught on Fire 17 The Wise King and the Baby 16 The World God Made 1 The World God Made 1 Three men Who Walked In Fire 18 Two Cities That Burned 16 When God Laid Down the Law 15 When God Made Balaam’s Donkey Talk 17 BIBLE STORY BOOKS A Child’s first Book of Bible Stories – For Boys and Girls from 5 – 9 Bible for Children with Songs & Plays Bible For Today’s Family Bible Picture Book Bible Stories (David Kossoff) Bible Stories (Heinemann & Ferguson) Bible Stories (Normal Vincent Peale) Bible Stories for Children Bible Story Book – The Complete Bible Story in chronological Order Children’s Stories of the Bible – from the Old Testament My Bible Picture Album Read n’ Grow Picture Bible Story Bible – Illustrated by Children The Bible in Pictures The Bible in Pictures for Little Eyes The Children’s Bible The Taize Picture Bible CHRISTMAS -

PROVISIONAL PROGRAM HNA Conference 2022

PROVISIONAL PROGRAM HNA Conference 2022 Amsterdam and The Hague, Netherlands HNA CONFERENCE 2022 Amsterdam and The Hague 2-4 June 2022 Program committee: Stijn Bussels, Leiden University (chair) Edwin Buijsen, Mauritshuis Suzanne Laemers, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History Judith Noorman, University of Amsterdam Gabri van Tussenbroek, University of Amsterdam | City of Amsterdam Abbie Vandivere, Mauritshuis and University of Amsterdam KEYNOTE LECTURES ClauDia Swan, Washington University A Taste for Piracy in the Dutch Republic 1 The global baroque world was a world of goods. Transoceanic trade routes compounded travel over land for commercial gain, and the distribution of wares took on global dimensions. Precious metals, spices, textiles, and, later, slaves were among the myriad commodities transported from west to east and in some cases back again. Taste followed trade—or so the story tends to be told. This lecture addresses the traffic in global goods in the Dutch world from a different perspective—piracy. “A Taste for Piracy in the Dutch Republic” will present and explore exemplary narratives of piracy and their impact and, more broadly, the contingencies of consumption and taste- making as the result of politically charged violence. Inspired by recent scholarship on ships, shipping, maritime pictures, and piracy this lecture offers a new lens onto the culture of piracy as well as the material goods obtained by piracy, and how their capture informed new patterns of consumption in the Dutch Republic. Jan Blanc, University of Geneva Dutch Seventeenth Century or Dutch Golden Age? Words, concepts and ideology Historians of seventeenth-century Dutch art have long been accustomed to studying not only works of art and artists, but also archives and textual sources. -

The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge 73

Rilke p. 33 THE NOTEBOOKS OF MALTE LAURIDS BRIGGE 73 THE PRODIGAL SON [Rilke's reflections in this novel on the Parable of the Prodigal deal with the fear of being loved and the way love seeks to mould a person in the expectations of the lover, which becomes an unbearable burden. One is reminded here of the work of Alice Miller on European child raising practices which refused to allow the individuality of the child to flourish: see Prisoners of Childhood, NY: Basic Books, 1981.] It would be difficult to persuade me that the story of the Prodigal Son is not the legend of a man who didn't want to be loved. When he was a child, everyone in the house loved him. He grew up not knowing it could be any other way and got used to their tenderness, when he was a child. But as a boy he tried to lay aside these habits. He wouldn't have been able to say it, but when he spent the whole day roaming around outside and didn't even want to have the dogs with him, it was because they too loved him; because in their eyes he could see observation and sympathy, expectation, concern; because in their presence too he couldn't do anything without giving pleasure or pain. But what he wanted in those days was that profound indifference of heart which sometimes, early in the morning, in the fields, seized him with such purity that he had to start running, in order to have no time or breath to be more than a weightless moment in which the morning becomes conscious of itself.