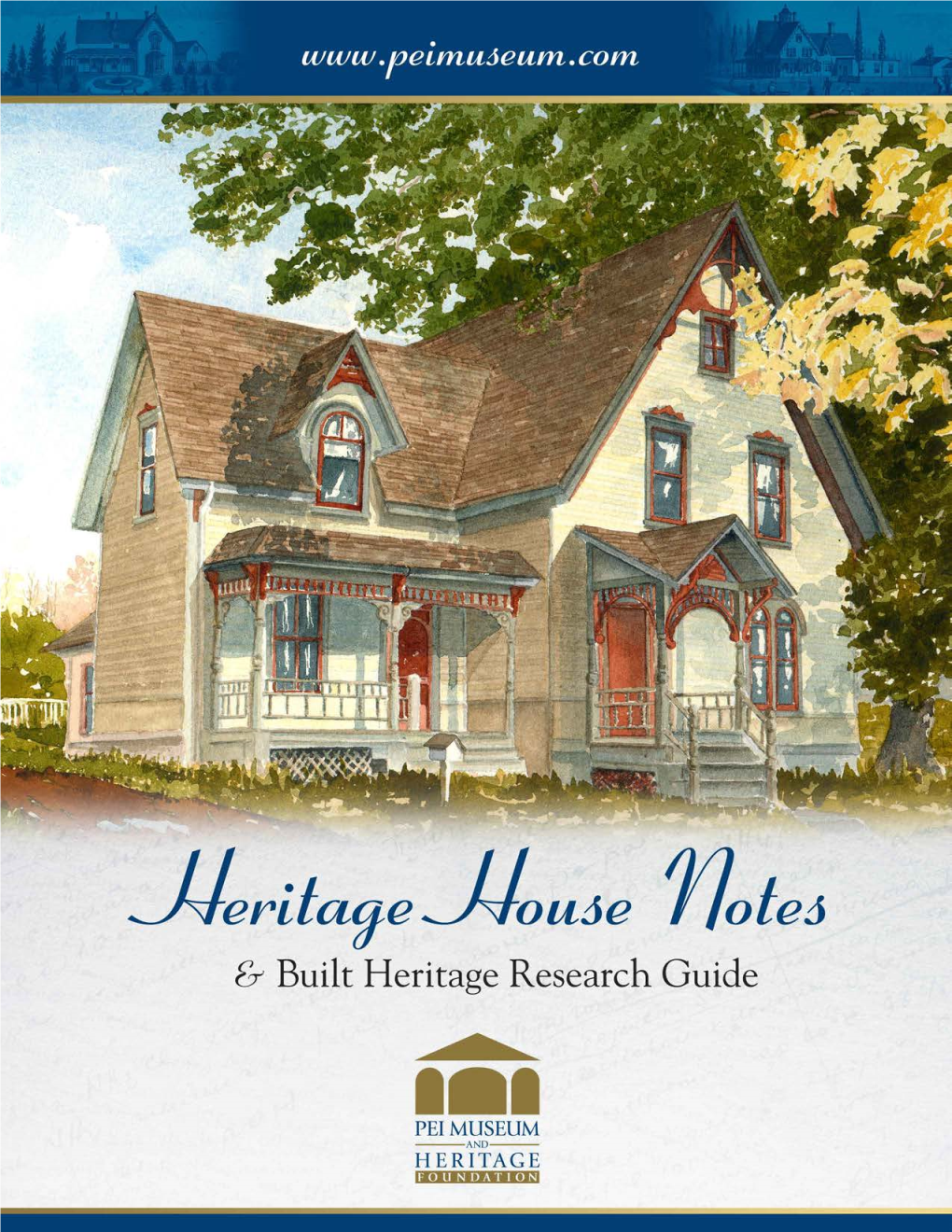

Heritage House Notes, Heritage Trading Cards and Posters, L.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charlottetown

NOTES © 2009 maps.com QUEBEC Charlottetown MAINE NOVA SCOTIA PORT EXPLORER n New York City Atlantic Ocea Charlottetown PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND, CANADA GENERAL INFORMATION “…but if the path set over the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. The island is justly famous for its beautiful before her feet was to be narrow she knew that flowers rolling farmland, scattered forests and dramatic coastline. There are numer- of quiet happiness would bloom along it…God is in his ous beaches, wetlands and sand dunes along Prince Edward Island’s beautiful heaven, all is right with the world, whispered Anne soft- coast. The hidden coves were popular with rum-runners during the days of ly.” Anne of Green Gables - Lucy Maud Montgomery – prohibition in the United States. 1908 The people of Prince Edward Island are justly proud of the fact that it was For many people over the past century their first and per- in Charlottetown in 1864 that legislative delegates from the Canadian prov- haps only impression of Prince Edward Island came from inces gathered to discuss the possibility of uniting as a nation. This meeting, reading LM Montgomery’s now classic book. The story now known as the Charlottetown Conference, was instrumental in the eventual is about a young orphan girl who is adopted and raised adoption of Canada’s Articles of Confederation. by a farming couple on Prince Edward Island. Many of Canada became a nation on July 1, 1867…not before names such as Albion, young Anne’s adventures and observations are said to be Albionoria, Borealia, Efisga, Hochelaga, Laurentia, Mesopelagia, Tuponia, based on Ms. -

Fathers of Confederation Buildings Trust Contents

2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT FATHERS OF CONFEDERATION BUILDINGS TRUST CONTENTS PROGRAMS SUPPORT 4 Theatre 16 Marketing and Communications 22 Financial Statements 8 Gallery 18 Development 24 Foundation 12 French Programming 19 Members IBC Friends 13 Heritage / Arts Education 21 Sponsors MESSAGE FROM THE CEO AND CHAIR OF THE BOARD The 2019-20 year has been a dynamic and exciting one for our artistic teams. Confederation Centre of the Arts stages were filled with music, drama, and laughter and welcomed visitors and artists from all over the world. Our galleries featured diverse and emerging artists who brought new live audiences here while receiving unprecedented digital media attention online. As we complete the first year of our 2019-24 Strategic Plan, we are entering into a global pandemic that has brought with it a paralyzing level of uncertainty. The Charlottetown Festival has been cancelled for the first time in its history, and Confederation Centre of the Arts has had to close its doors entirely as of March 16, 2020. What lies beyond the summer is unknown, so for now we are following the guidance of the Chief Public Health Officer and the Province of PEI – guidance which is updated daily and will ultimately indicate when and in what way we can reopen, and how gathering restrictions will impact our ability to deliver various programs. We remain committed to our Strategic Plan and our three pillars of Artistic Excellence, Engaged Diverse Communities, and Organizational Sustainability. We remain committed to our 12 priority areas as outlined in the plan, and the many resulting goals and actions that are part of our implementation plan. -

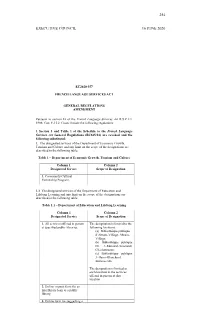

Orders in Council, June 16, 2020

254 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL _________________________________16 JUNE 2020 EC2020-357 FRENCH LANGUAGE SERVICES ACT GENERAL REGULATIONS AMENDMENT Pursuant to section 16 of the French Language Services Act R.S.P.E.I. 1988, Cap. F-15.2, Council made the following regulations: 1. Section 1 and Table 1 of the Schedule to the French Language Services Act General Regulations (EC845/13) are revoked and the following substituted: 1. The designated services of the Department of Economic Growth, Tourism and Culture and any limit on the scope of the designations are described in the following table: Table 1 – Department of Economic Growth, Tourism and Culture Column 1 Column 2 Designated Service Scope of Designation 1. Community Cultural Partnership Program. 1.1 The designated services of the Department of Education and Lifelong Learning and any limit on the scope of the designations are described in the following table: Table 1.1 – Department of Education and Lifelong Learning Column 1 Column 2 Designated Service Scope of Designation 1. All services offered in person The designation is limited to the at specified public libraries. following locations: (a) Bibliothèque publique d’Abram-Village, Abram- Village; (b) Bibliothèque publique Dr. J.-Edmond-Arsenault, Charlottetown; (c) Bibliothèque publique J.-Henri-Blanchard, Summerside. The designation is limited at each location to the services offered in person at that location. 2. Online request form for an interlibrary loan to a public library. 3. Online form for suggesting a 255 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL _________________________________16 JUNE 2020 purchase for a public library. 4. Online application form for a public library card. 5. Online registration form for accessible public library services. -

Royal Gazette, November 16, 2013

Prince Edward Island Postage paid in cash at First Class Rates PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY VOL. CXXXIX–NO. 46 Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, November 16, 2013 CANADA PROVINCE OF PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND IN THE SUPREME COURT - ESTATES DIVISION TAKE NOTICE that all persons indebted to the following estates must make payment to the personal representative of the estates noted below, and that all persons having any demands upon the following estates must present such demands to the representative within six months of the date of the advertisement: Estate of: Personal Representative: Date of Executor/Executrix (Ex) Place of the Advertisement Administrator/Administratrix (Ad) Payment DENNIS, Gordon Roy Gail B. Dennis (EX.) McInnes Cooper Mayfield 119 Kent Street (formerly of Charlottetown) Charlottetown, PE Queens Co., PE November 16, 2013 (46-7)* DODSWORTH, Merle Stewart Jerrilyn Lee Rinaldi Carr Stevenson & MacKay Eldon Lester Charles Dodsworth (EX.) 65 Queen Street Queens Co., PE Charlottetown, PE November 16, 2013 (46-7)* GALLANT, Joanne Terry Gallant (EX.) Carla L. Kelly Law Office St. Louis 100-102 School Street Prince Co., PE Tignish, PE November 16, 2013 (46-7)* GRAMS, Elizabeth Ruth Barbara Pringle Stewart McKelvey Orwell Lee Fischer (EX.) 65 Grafton Street Queens Co., PE Charlottetown, PE November 16, 2013 (46-7)* NEWELL, Roy Arnett Reynolds (EX.) Stewart McKelvey Murray Harbour 65 Grafton Street Kings Co., PE Charlottetown, PE November 16, 2013 (46-7)* *Indicates date of first publication in the Royal Gazette. This is the official version -

Charlottetown

Charlottetown Charlottetown, the Island’s abound. Foodies will rejoice Downtown Charlottetown capital city, strikes a perfect at the diversity of restaurants, brims with history, artistry and balance, pairing small town cafes and pubs featuring menus energy. Built for exploring on charm with big city energy. inspired by the Island’s rich foot, the area is filled with a With its romantic streetscapes, bounty of food from land and colourful mix of independent stunning water vistas and sea. And if you thirst for unique shops, restaurants, elegantly sun-dappled patios, this brews you’ll happily discover restored heritage buildings and enchanting coastal city offers Charlottetown is home to a lush green spaces. Take pause a welcome escape from the burgeoning craft beer scene, during your stroll to marvel at hustle and bustle. with must-stops at the the public monuments that Live music, public art, PEI Brewing Company, Upstreet pay homage to the city’s proud Charlottetown festivals, theatre and other Craft Brewing and Gahan House history and unique role as the entertainment options Pub & Brewery. Birthplace of Confederation. ANN MACNEILL ANN Confederation Players/Confederation Harness Racing/ 5 JOHN SYLVESTER; JOHN 1 2 4 3 Victoria Park/ STEPHEN HARRIS; STEPHEN HARRIS; / 140 This map does not contain all the place names and roads on the Island. For detailed VictoriaPhotos: Row information refer to the official full-size PEI Highway Map. Sample itinerary A taste of what to see and do in Charlottetown. CONFEDERATION HARNESS RACING CENTRE OF THE ARTS A unique Island The Confederation Centre of experience that’s the1 Arts is the Island’s premier spanned many generations, theatre and features live enter- 5 harness racing remains tainment year-round–from a much beloved Island musicals to symphonies and tradition. -

Communities in Bloom 2017

Communities in Bloom 2017 Greetings from the Mayor It is an honor for me as Mayor of the Capital City of Prince Edward Island and the “Birthplace of Confederation” to extend a warm welcome to Alain and Cliff, our 2017 Communities In Bloom National Judges, to Charlottetown. Welcome to our historic and beautiful City. Charlottetown is a major tourist destination and we understand the importance of beautification to our local economy. In 2014 Charlottetown was named the number one tourism destination in Canada by vacay.com. Our tourism numbers continue to rise each year and Charlottetown, the Capital City, continues to work hard to ensure our City remains clean, tidy, and at the same time recognizes the importance of community development and environmental awareness to the overall growth of our community. On behalf of City Council and the residents of this City, I hope that you enjoy the itinerary provided to you; enjoy our knowledgeable and hospitable staff and please do not hesitate to provide your input and suggestions to our staff on how we can improve ourselves going forward. In 2017, in recognition of Canada’s 150th Birthday, we celebrate this beautiful country we call Canada. We are proud to be Canadian. On your drive around you will see many initiatives to recognize Canada 150. Yours truly, Clifford J. Lee MAYOR Contents Community Profile 1 Canada 150 Signature Events 3 Tidiness 9 Environmental Action 12 Heritage Conservation 20 Urban Forestry 26 Floral Displays 29 Landscape 31 Signature Events 34 Partners 38 Community Profile The City of Charlottetown is a flourishing community of over 34,562 people located on the south shore of Prince Edward Island. -

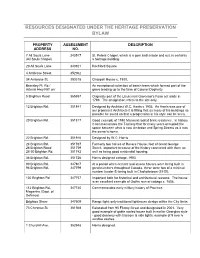

Resources Designated Under the Heritage Preservation Bylaw

RESOURCES DESIGNATED UNDER THE HERITAGE PRESERVATION BYLAW PROPERTY ASSESSMENT DESCRIPTION ADDRESS NO. 7 All Souls Lane 343517 St. Peters Chapel, which is a gem both inside and out, is certainly (All Souls Chapel) a heritage building. 20 All Souls Lane 343921 Rochford Square 4 Ambrose Street 352062 34 Ambrose St. 353318 Chappell House c. 1930. Brackley Pt. Rd./ An exceptional collection of beech trees which formed part of the Arterial Hwy NW cnr grove leading up to the farm of Colonel Dogherty 5 Brighton Road 365957 Originally part of the Lieutenant Governor’s Farm set aside in 1789. The designation refers to the site only. 12 Brighton Rd. 351841 Designed by Architect W.C. Harris c 1905. As Harris was one of our prominent Architects it is fitting that as many of his buildings as possible be saved so that a progression in his style can be seen. 20 Brighton Rd. 351817 Good example of 1880 Mansard roofed brick residence. In history it commemorates the Tannery that for many years occupied the space between what is now Ambrose and Spring Streets as it was the owner's home. 22 Brighton Rd. 351916 Designed by W.C. Harris. 24 Brighton Rd. 351767 Formerly two halves of Revere House, foot of Great George 26 Brighton Road 351759 Street. Important because of the history connected with them as 28-30 Brighton Rd. 351742 well as being good residential housing. 36 Brighton Rd. 351726 Harris designed cottage, 1903. 90 Brighton Rd. 347807 At a period when cement and stucco houses were being built in 94 Brighton Rd. -

Municipal Statistical Review for Prince Edward Island Municipalities for the Year

Finance and Municipal Affairs Municipal Statistical Review for Prince Edward Island municipalities for the year 2008/2009 Prepared By: Municipal Affairs and Provincial Planning Aubin Arsenault Building 3 Brighton Road Charlottetown, PE C1A 7N8 Tel: 368-5892 Fax: 368-5526 Message from the Minister __________________________________________ It is my privilege, as Minister of Finance and Municipal Affairs, to present the Municipal Statistical Review for the year of 2008. This review incorporates the statistical information on financial expenditures, population, services offered by municipalities, planning and municipal assessments. I would like to express my sincere appreciation to all municipalities for their assistance in completing the required documentation. They provided a great deal of the information in this report, along with Statistics Canada and various government departments. The result of this collaboration is an overview of the services provided by our Island municipalities to residents on a daily basis. I’m sure you will find it to be very informative. You may also find additional resources for municipalities by visiting our departmental website at: http://www.gov.pe.ca/finance/municipalaffairs Wes Sheridan Minister of Finance and Municipal Affairs Table of Contents Statistical Highlights 3 Chart 1: County Population 3 Municipal Fact Sheet 5 Chart 2: Municipal Expenditures 5 Table 1: Commercial and Non-Commercial Tax Rates 6 Chart 3: Comparison of Municipal Administration 6 Chart 4: Municipal Acreage 7 Chart 5: Municipal Populations -

National Historic Sites of Canada System Plan Will Provide Even Greater Opportunities for Canadians to Understand and Celebrate Our National Heritage

PROUDLY BRINGING YOU CANADA AT ITS BEST National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Parks Parcs Canada Canada 2 6 5 Identification of images on the front cover photo montage: 1 1. Lower Fort Garry 4 2. Inuksuk 3. Portia White 3 4. John McCrae 5. Jeanne Mance 6. Old Town Lunenburg © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, (2000) ISBN: 0-662-29189-1 Cat: R64-234/2000E Cette publication est aussi disponible en français www.parkscanada.pch.gc.ca National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Foreword Canadians take great pride in the people, places and events that shape our history and identify our country. We are inspired by the bravery of our soldiers at Normandy and moved by the words of John McCrae’s "In Flanders Fields." We are amazed at the vision of Louis-Joseph Papineau and Sir Wilfrid Laurier. We are enchanted by the paintings of Emily Carr and the writings of Lucy Maud Montgomery. We look back in awe at the wisdom of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. We are moved to tears of joy by the humour of Stephen Leacock and tears of gratitude for the courage of Tecumseh. We hold in high regard the determination of Emily Murphy and Rev. Josiah Henson to overcome obstacles which stood in the way of their dreams. We give thanks for the work of the Victorian Order of Nurses and those who organ- ized the Underground Railroad. We think of those who suffered and died at Grosse Île in the dream of reaching a new home. -

Download the Music Market Access Report Canada

CAAMA PRESENTS canada MARKET ACCESS GUIDE PREPARED BY PREPARED FOR Martin Melhuish Canadian Association for the Advancement of Music and the Arts The Canadian Landscape - Market Overview PAGE 03 01 Geography 03 Population 04 Cultural Diversity 04 Canadian Recorded Music Market PAGE 06 02 Canada’s Heritage 06 Canada’s Wide-Open Spaces 07 The 30 Per Cent Solution 08 Music Culture in Canadian Life 08 The Music of Canada’s First Nations 10 The Birth of the Recording Industry – Canada’s Role 10 LIST: SELECT RECORDING STUDIOS 14 The Indies Emerge 30 Interview: Stuart Johnston, President – CIMA 31 List: SELECT Indie Record Companies & Labels 33 List: Multinational Distributors 42 Canada’s Star System: Juno Canadian Music Hall of Fame Inductees 42 List: SELECT Canadian MUSIC Funding Agencies 43 Media: Radio & Television in Canada PAGE 47 03 List: SELECT Radio Stations IN KEY MARKETS 51 Internet Music Sites in Canada 66 State of the canadian industry 67 LIST: SELECT PUBLICITY & PROMOTION SERVICES 68 MUSIC RETAIL PAGE 73 04 List: SELECT RETAIL CHAIN STORES 74 Interview: Paul Tuch, Director, Nielsen Music Canada 84 2017 Billboard Top Canadian Albums Year-End Chart 86 Copyright and Music Publishing in Canada PAGE 87 05 The Collectors – A History 89 Interview: Vince Degiorgio, BOARD, MUSIC PUBLISHERS CANADA 92 List: SELECT Music Publishers / Rights Management Companies 94 List: Artist / Songwriter Showcases 96 List: Licensing, Lyrics 96 LIST: MUSIC SUPERVISORS / MUSIC CLEARANCE 97 INTERVIEW: ERIC BAPTISTE, SOCAN 98 List: Collection Societies, Performing -

Home Improvement Television: Holmes on Homes Makes It Right

Home Improvement Television: Holmes on Homes Makes It Right Jean Bruce Ryerson University Abstract: Holmes on Homes is a Canadian home improvement television program and the centrepiece of HGTV (Home and Garden Television), featuring Mike Holmes as the series’ star contractor and host. This paper argues that by looking back at earlier incarnations of film and television melodrama, we can determine the way in which Holmes on Homes reinvents the home improvement subgenre. By playing out reality TV’s central tension between fiction and non-fiction, Holmes on Homes reveals its larger themes of justice and redemption, which befit its unique position between the documentary and the classic melodrama. Keywords: Reality TV; Holmes on Homes; Home improvement television; Documentary TV; Classic melodrama Résumé : Holmes on Homes, mettant en vedette l’entrepreneur Mike Holmes, est une émission canadienne sur l’amélioration du foyer et la pièce de résistance du réseau HGTV (Home and Garden Television). Cet article soutient que nous pouvons recourir à des exemples anciens de mélodrames à la télévision et au cinéma, pour déterminer la manière dont cette émission réinvente le sous-genre « amélioration du foyer ». En effet, Holmes on Homes, en développant les tensions centrales de la téléréalité entre fiction et vérité, révèle ses thèmes clés de justice de rédemption qui reflètent sa position unique entre documentaire et mélodrame classique. Mots clés : Téléréalité; Holmes on Homes; Télévision sur l’amélioration du foyer; Télévision documentaire; Mélodrame classique Introduction When specialty network Home and Garden Television (HGTV) Canada applied for its broadcasting licence in 1996, the “nature of the service” it would provide was described as follows: The licensee will offer a 24-hour-a-day specialty service devoted to pro- gramming that presents practical, hands-on advice and instruction about homes and gardens. -

Helping Restore Native Bay Oysters Page 1 of 4

wjz.com - 'Reef Balls' Helping Restore Native Bay Oysters Page 1 of 4 WJZ Baltimore, Maryland News Weather: 'Reef Balls' Helping Restore Native Bay Oysters Advertisement Seen On Oct 20, 2006 1:14 pm US/Eastern 'Reef Balls' Helping Restore Native Bay Oysters Alex DeMetrick Reporting (WJZ) Officials from the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) say they have seen a significant success in Eastern Bay, near Kent Island, that shows using "reef balls" can be a successful approach to restoring the native Bay oyster. CBF and project partners Maryland Environmental Service (MES) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) will host boat trips to the reef ball site, and will lift several out of the water to highlight the project's accomplishments. Reef balls without oysters will be available on the boat for visual comparisons. CBF, MES and NOAA, with funding from the Fish America Foundation, planted 69 reef balls on the site in 2005. Twenty "set," meaning tiny oysters had attached to the reef balls at CBF's Oyster Restoration Center. Less than one year after they were placed on the Eastern Bay reef, these oysters have grown over two inches in length, and have an excellent survival rate. Reef balls - large, igloo-like concrete structures - are still a relatively new approach to restoring oysters to the planted in the Bay, and oysters can attach themselves to the concrete "reefs." There, the oysters can grow into adults, filtering pollutants from the water and creating a rich habitat for fish and other creatures. Project partners also include CBF and South River Federation volunteers, who helped create the reef balls.