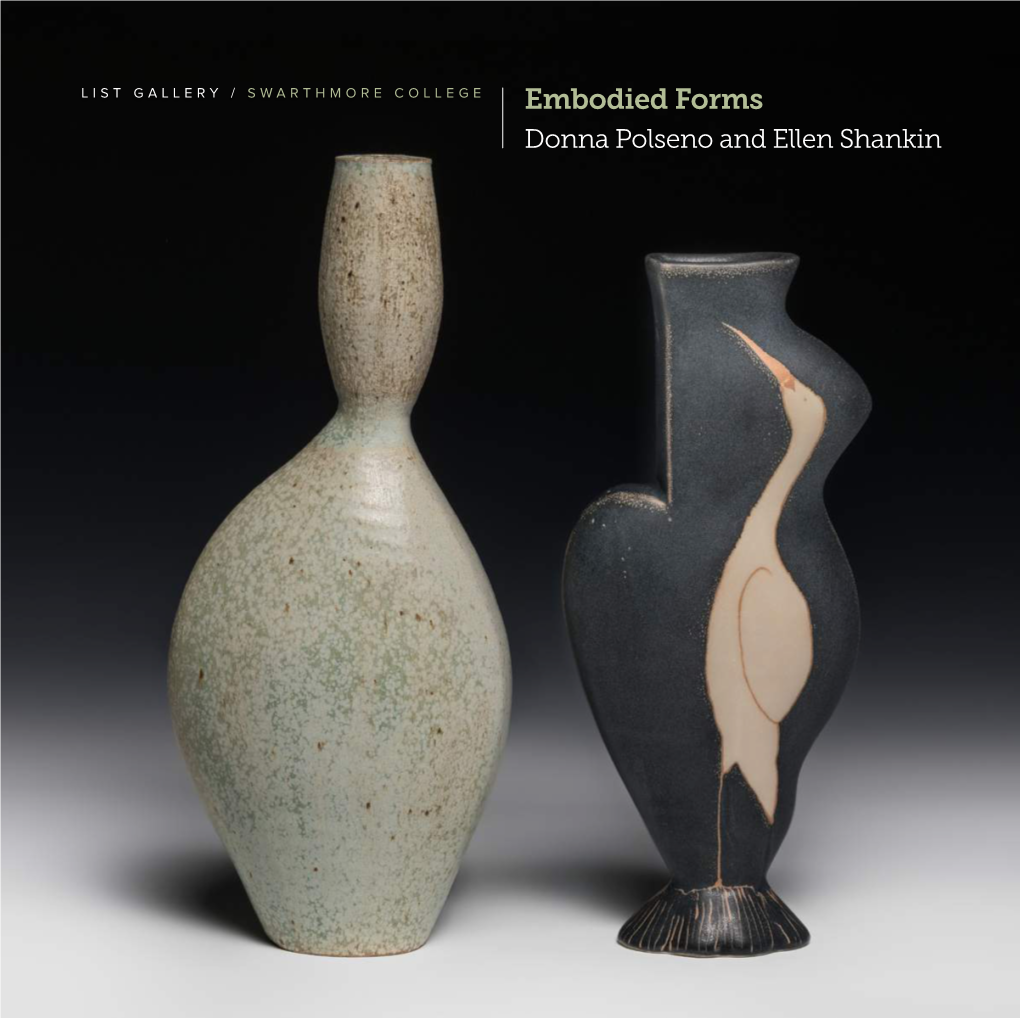

Embodied Forms Donna Polseno and Ellen Shankin Embodied Forms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multiplicity: Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture' Exhibition Catalog Anne M Giangiulio, University of Texas at El Paso

University of Texas at El Paso From the SelectedWorks of Anne M. Giangiulio 2006 'Multiplicity: Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture' Exhibition Catalog Anne M Giangiulio, University of Texas at El Paso Available at: https://works.bepress.com/anne_giangiulio/32/ Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture Organized by the Stanlee and Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts at the University of Texas at El Paso This publication accompanies the exhibition Multiplicity: Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture which was organized by the Stanlee and Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts at the University of Texas at El Paso and co-curated by Kate Bonansinga and Vincent Burke. Published by The University of Texas at El Paso El Paso, TX 79968 www.utep.edu/arts Copyright 2006 by the authors, the artists and the University of Texas at El Paso. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the University of Texas at El Paso. Exhibition Itinerary Portland Art Center Portland, OR March 2-April 22, 2006 Stanlee and Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture The University of Texas at El Paso El Paso, TX June 29-September 23, 2006 San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts San Angelo, TX April 20-June 24, 2007 Landmark Arts Texas Tech University Lubbock, TX July 6-August 17, 2007 Southwest School of Art and Craft San Antonio, TX September 6-November 7, 2007 The exhibition and its associated programming in El Paso have been generously supported in part by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the Texas Commission on the Arts. -

JESSE RING: Sculpture

CV JESSE RING: sculpture EDUCATION -2013-2015 MFA in Ceramics, New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University, Alfred, NY |AlfredCeramics.com -2002-2006 BFA in Ceramics with minor studies in Painting, Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, MO. | KCAI.edu SOLO EXHIBITIONS -2015 “Paper Moon”, Thesis Exhibition, Fosdick Nelson Gallery, Alfred University, Alfred, NY. (Curatorial Advisor Sharon McConnell) -2012 “Moonlight Mythstakes & Summerscape-isms” Carbondale Clay Center, Carbondale, CO. (Curated by K Cesark) -2011 “Enshrined” Springfield Pottery, Springfield, MO -2010 “Monuments Too” Gilloiz Theater Lobby, Springfield, MO “Collagescape” The Albatross, Springfield, MO. June 2010- Jan 2011 -2008 “Vagrant Opulence” Via Viva, Mural Opening, Carbondale, CO. SELECTED EXHIBITIONS -2017 “Confluence and Bifurcations” NCECA Exhibition, Oregon College of Art and Craft, Portland, OR. -2016 “Modern Makers” Bathgate, Cincinatti, OH. (Jurors:) “SOFA Chicago” University of Cincinatti Booth 220, Chicago, IL. “Inhale” Aotu Studio, Beijing, China. (Curator Jialin Yang) “Bang Bang” Open Gate Gallery, Caochangdi, Beijing, China “Planning the Improbable, Sketching the Impossible” Washington Street Arts Center, Invitational, Boston, MA (Curator Mitch Shiles) “Clay Landmarks” The Arabia Steamboat Museum, Invitational Site Specific Group Show, Kansas City, MO. (Curator Allison Newsome) -2015 “Art in Craft Media-2015” Burchfield Penny Museum, Buffalo, NY. (Juror Wayne Higby, Curator Scott Propeak) “ Midwest Life Vest” University of Nebraska Kearney, Kearny, NS. (Curator Amy Santoferarro) “History in the Making” Carbondale Clay Center, Carbondale, CO. (Curator Jill Oberman) “Variance” The Wurks Gallery, Providence, RI. -2013 “Sustain” Art House Delray, Delray Beach, FL. (Curators Jade Henderson and Chelsea Odum) “Resident Artist Show” Armory Art Center, West Palm Beach, FL. “Beyond the Brickyard” Archie Bray Foundation, Helena, MT. -

Tactile Digital: an Exploration of Merging Ceramic Art and Industrial Design

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ENGINEERING AND PRODUCT DESIGN EDUCATION 8 & 9 SEPTEMBER 2016, AALBORG UNIVERSITY, DENMARK TACTILE DIGITAL: AN EXPLORATION OF MERGING CERAMIC ART AND INDUSTRIAL DESIGN Dosun SHIN1 and Samuel CHUNG2 1Industrial Design, Arizona State University 2Ceramic Art, Arizona State University ABSTRACT This paper presents a pilot study that highlights collaboration between ceramic art and industrial design. The study is focused on developing a ceramic lamp that can be mass-produced and marketed as a design artefact. There are two ultimate goals of the study: first, to establish an iterative process of collaboration between ceramic art and industrial design through an example of manufactured design artefact and second to expand transdisciplinary and collaborative knowledge. Keywords: Trans-disciplinary collaboration, emerging design technology, ceramic art, industrial design. 1 INTRODUCTION The proposed project emphasizes collaboration between disciplines of ceramic art and industrial design to create a ceramic lamp that can be mass-produced and marketed as a design artefact. It addresses issues related to disciplinary challenges involved in the process and use of prototyping techniques that make this project unique. There are two ultimate goals of the project. First is to establish an iterative process of collaboration between ceramic art and industrial design through an example of manufactured 3D ceramic lamp. The second goal is to develop a transdisciplinary ceramic design course for Arizona State University students. The eventual intent is also to share generated knowledge with scholars from academia and industry through various conferences, academic, and technical platforms. In the following, we will first discuss theoretical perspectives about collaboration between ceramic art and industrial design to highlight positives and negatives of disciplinary associations. -

Curriculum Vitae Ezra Shales, Ph.D. [email protected] Professor

Curriculum Vitae Ezra Shales, Ph.D. [email protected] Professor, Massachusetts College of Art and Design Publications Books Holding Things Together (in process) Revised editions and introductions to David Pye, Nature and Art of Workmanship (1968) and Pye, Nature and Aesthetics of Design (1964) (Bloomsbury Press, 2018) The Shape of Craft (Reaktion Books, anticipated publication Winter 2017-2018) Made in Newark: Cultivating Industrial Arts and Civic Identity in the Progressive Era (Rutgers University Press, 2010) Peer-Reviewed Scholarly Publications “Craft” in Textile Terms: A Glossary, ed. Reineke, Röhl, Kapustka and Weddigen (Edition Immorde, Berlin, 2016), 53-56 “Throwing the Potter’s Wheel (and Women) Back into Modernism: Reconsidering Edith Heath, Karen Karnes, and Toshiko Takaezu as Canonical Figures” in Ceramics in America 2016 (Chipstone, 2017), 2-30 “Eva Zeisel Recontextualized, Again: Savoring Sentimental Historicism in Tomorrow’s Classic Today” Journal of Modern Craft vol. 8, no. 2 (November 2015): 155-166 “The Politics of ‘Ordinary Manufacture’ and the Perils of Self-Serve Craft,” Nation Building: Craft and Contemporary American Culture (Smithsonian American Art Museum, 2015), 204-221 “Mass Production as an Academic Imaginary,” Journal of Modern Craft vol. 6, no. 3 (November 2013): 267-274 “A ‘Little Journey’ to Empathize with (and Complicate) the Factory,” Design & Culture vol. 4, no. 2 (Summer 2012): 215-220 “Decadent Plumbers Porcelain: Craft and Modernity in Ceramic Sanitary Ware,” Kunst Og Kultur (Norwegian Journal of Art and Culture) vol. 94, no. 3 (Fall 2011): 218-229 “Corporate Craft: Constructing the Empire State Building,” Journal of Modern Craft vol. 4, no. 2 (July 2011): 119-145 “Toying with Design Reform: Henry Cole and Instructive Play for Children,” Journal of Design History vol. -

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

Rilzler School of Art, Rernple, Univergl*:."10*:G:T$Ttl,Rlt

RESUME PAULA COIJTON WINOKUR. 435 Norristown Road Horsham, Pennsylvania L9044 2L5/675-7708 EDUCATION rilzler school of Art, rernple, univergl*:."10*:g:t$ttl,rlt, State University of New York at Alfred, Alfred, New York College of Ceramics, Summer 1958 i l IEACHING EXPERIENCE l I 1968-69 PhiLadelphia College of Art - Ceramics l 1973-present Beaver College, Glenside, PA - Ceramics J PROFESSIONAL ORGANI ZATIONS : 1968-1973 Philad.elphia Council of Professional Craftsmen, Treasurer Lg72-L976 American Crafts Council, Pennsylvania Representa- tive to the Northeast Regional Assembly L979-L982 National Council on Education in the Ceramic Arts, Chairman, Liaison Committee REPRESENTED BY: IIeIen Drutt Gallery, Philadelprr'ia, PA P. Winokur - 2 GRANTS 1973 New Jersey Council on the Arts,/Montclair State College summer apprentj-ce program: student apprentice and stipend L97 4 Pennsylvania Council on the Arts,/ACC/NE Summer apprentice programs student apprentice and stipend L976 National Endowment for the Arts Craftsmens Fellowship COMMTSSIONS 1969 Ford and Earl ArchitecturaL Designers, Detroit, Michigan - for the First Uationat Bank of Chicago, a series of J-arge planters 19 75 Eriends Sel-ect School, phiJ_adelphia pA Patrons Plate, limited edition - EOLLECTTONS 1950 Witte }luseum of Art, San Antonio TX 1966 Mr. & !{rs. Francis Merritt, Deer IsIe ME 1969 Mr. Yamanaka, Cu1tural Attache to the Japanese Embassy, Washington DC 19 70 Philadelphia Museum of Art - 20th Century Decorative Arts Collection L970/72 Helen Williams Drutt, philadelphia pA 19 71 l4r. Ken Deavers, The American Hand Gallery L972 Delaware Museum of Art - permanent Collection 1973 Alberta Potters Association, Calgary, Canada L975 Mrs. Anita Rosenblum, Chicago IL 19 75 Jean Mannheim, Des Moines IA L976 Utah Museum of Art, Salt Lake City UT L97 6 Mr. -

9. Ceramic Arts

Profile No.: 38 NIC Code: 23933 CEREMIC ARTS 1. INTRODUCTION: Ceramic art is art made from ceramic materials, including clay. It may take forms including art ware, tile, figurines, sculpture, and tableware. Ceramic art is one of the arts, particularly the visual arts. Of these, it is one of the plastic arts. While some ceramics are considered fine art, some are considered to be decorative, industrial or applied art objects. Ceramics may also be considered artifacts in archaeology. Ceramic art can be made by one person or by a group of people. In a pottery or ceramic factory, a group of people design, manufacture and decorate the art ware. Products from a pottery are sometimes referred to as "art pottery".[1] In a one-person pottery studio, ceramists or potters produce studio pottery. Most traditional ceramic products were made from clay (or clay mixed with other materials), shaped and subjected to heat, and tableware and decorative ceramics are generally still made this way. In modern ceramic engineering usage, ceramics is the art and science of making objects from inorganic, non-metallic materials by the action of heat. It excludes glass and mosaic made from glass tesserae. There is a long history of ceramic art in almost all developed cultures, and often ceramic objects are all the artistic evidence left from vanished cultures. Elements of ceramic art, upon which different degrees of emphasis have been placed at different times, are the shape of the object, its decoration by painting, carving and other methods, and the glazing found on most ceramics. 2. -

Museum of Arts and Design

SPRING/SUMMER BULLETIN 2011 vimuseume of artsws and design Dear Friends, Board of Trustees Holly Hotchner LEWIS KRUGER Nanette L. Laitman Director Chairman What a whirlwind fall! Every event seemed in some way or another a new milestone for JEROME A. CHAZEN us all at 2 Columbus Circle. And it all started with a public program that you might have Chairman Emeritus thought would slip under the radar—Blood into Gold: The Cinematic Alchemy of Alejandro BARbaRA TOBER Chairman Emerita Jodorowsky. Rather than attracting a small band of cinéastes, this celebration of the Chilean- FRED KLEISNER born, Paris-based filmmaker turned into a major event: not only did the screenings sell Treasurer out, but the maestro’s master class packed our seventh-floor event space to fire-code LINDA E. JOHNSON Secretary capacity and elicited a write-up in the Wall Street Journal! And that’s not all, none other HOllY HOtcHNER than Debbie Harry introduced Jodorowsky’s most famous filmThe Holy Mountain to Director filmgoers, among whom were several downtown art stars, including Klaus Biesenbach, the director of MoMA PS1. A huge fan of this mystical renaissance man, Biesenbach was StaNLEY ARKIN DIEGO ARRIA so impressed by our series that beginning on May 22, MoMA PS1 will screen The Holy GEORGE BOURI Mountain continuously until June 30. And, he has graciously given credit to MAD and KAY BUckSbaUM Jake Yuzna, our manager of public programs, for inspiring the film installation. CECILY CARSON SIMONA CHAZEN MICHELE COHEN Jodorowsky wasn’t the only Chilean artist presented at MAD last fall. Several had works ERIC DObkIN featured in Think Again: New Latin American Jewelry. -

Ford Ceramic Arts Columbus, Ohio

The Journal of the American Art Pottery Association, v.14, n. 2, p. 12-14, 1998. © American Art Pottery Association. http://www.aapa.info/Home/tabid/120/Default.aspx http://www.aapa.info/Journal/tabid/56/Default.aspx ISSN: 1098-8920 Ford Ceramic Arts Columbus, Ohio By James L. Murphy For about five years during the late 1930s, the combination of inventive and artistic talent pro- vided by Walter D. Ford (1906-1988) and Paul V. Bogatay (1905-1972), gave life to Ford Ceramic Arts, Inc., a small and little-known Columbus, Ohio, firm specializing in ceramic art and design. The venture, at least in the beginning, was intimately associated with Ohio State University (OSU), from which Ford graduated in 1930 with a degree in Ceramic Engineering, and where Bogatay began his tenure as an instructor of design in 1934. In fact, the first plant, begun in 1936, was actually located on the OSU campus, at 319 West Tenth Avenue, now the site of Ohio State University’s School of Nursing. There two periodic kilns produced “decorated pottery and dinnerware, molded porcelain cameos, and advertising specialties.” Ford was president and ceramic engineer; Norman M. Sullivan, secretary, treasurer, and purchasing agent; Bogatay, art director. Subsequently, the company moved to 4591 North High Street, and Ford's brother, Byron E., became vice-president. Walter, or “Flivver” Ford, as he had been known since high school, was interested primarily in the engineering aspects of the venture, and it was several of his processes for producing photographic images in relief or intaglio on ceramics that distinguished the products of the company. -

WHITE IRONSTONE NOTES VOLUME 3 No

WHITE IRONSTONE NOTES VOLUME 3 No. 2 FALL 1996 By Bev & Ernie Dieringer three sons, probably Joseph, The famous architect Mies van was the master designer of the der Rohe said, “God is in the superb body shapes that won a details.” God must have been in prize at the Crystal Palace rare form in the guise of the Exhibition in 1851. master carver who designed the Jewett said in his 1883 book handles and finials for the The Ceramic Art of Great Mayer Brothers’ Classic Gothic Britain, “Joseph died prema- registered in 1847. On page 44 turely through excessive study in Wetherbee’s collector’s guide, and application of his art. He there is an overview of the and his brothers introduced Mayer’s Gothic. However, we many improvements in the man- are going to indulge ourselves ufacture of pottery, including a and perhaps explain in words stoneware of highly vitreous and pictures, why we lovingly quality. This stoneware was collect this shape. capable of whithstanding varia- On this page, photos show tions of temperature which details of handles on the under- occurred in the brewing of tea.” trays of three T. J. & J. Mayer For this profile we couldn’t soup tureens. Top: Classic find enough of any one T. J. & J. Octagon. Middle: Mayer’s Mayer body shape, so we chose Long Octagon. Bottom: Prize a group of four shapes, includ- Bloom. ing the two beautiful octagon Elijah Mayer, patriarch of a dinner set shapes, the Classic famous family of master potters, Gothic tea and bath sets and worked in the last quarter of the Prize Bloom. -

Volume 18 (2011), Article 3

Volume 18 (2011), Article 3 http://chinajapan.org/articles/18/3 Lim, Tai Wei “Re-centering Trade Periphery through Fired Clay: A Historiography of the Global Mapping of Japanese Trade Ceramics in the Premodern Global Trading Space” Sino-Japanese Studies 18 (2011), article 3. Abstract: A center-periphery system is one that is not static, but is constantly changing. It changes by virtue of technological developments, design innovations, shifting centers of economics and trade, developmental trajectories, and the historical sensitivities of cultural areas involved. To provide an empirical case study, this paper examines the material culture of Arita/Imari 有田/伊万里 trade ceramics in an effort to understand the dynamics of Japan’s regional and global position in the transition from periphery to the core of a global trading system. Sino-Japanese Studies http://chinajapan.org/articles/18/3 Re-centering Trade Periphery through Fired Clay: A Historiography of the Global Mapping of Japanese Trade Ceramics in the 1 Premodern Global Trading Space Lim Tai Wei 林大偉 Chinese University of Hong Kong Introduction Premodern global trade was first dominated by overland routes popularly characterized by the Silk Road, and its participants were mainly located in the vast Eurasian space of this global trading area. While there are many definitions of the Eurasian trading space that included the so-called Silk Road, some of the broadest definitions include the furthest ends of the premodern trading world. For example, Konuralp Ercilasun includes Japan in the broadest definition of the silk route at the farthest East Asian end.2 There are also differing interpretations of the term “Silk Road,” but most interpretations include both the overland as well as the maritime silk route. -

Research on the Specific Application of Ethnic Elements in Dynamic Visual Communication Design Based on Intangible Cultural Heritage

2019 7th International Education, Economics, Social Science, Arts, Sports and Management Engineering Conference (IEESASM 2019) Research on the Specific Application of Ethnic Elements in Dynamic Visual Communication Design Based on Intangible Cultural Heritage Ren Ruiyao Xi’an University, Shaanxi, Xi’an 710065, China Keywords: Intangible Cultural Heritage, Dynamic Visual Communication Design, National Element Abstract: from the Perspective of Inheritance and Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage, by Widely Applying National Elements to the Field of Dynamic Visual Communication Design, Not Only Can Its Design Connotation Be Improved, But Also Be Conducive to the Transmission of Intangible Cultural Heritage. This Paper First Analyzes the Relationship between the Inheritance of Intangible Cultural Heritage and Dynamic Visual Communication Design, Then Discusses the Application Value of Ethnic Elements in Dynamic Visual Communication Design, and Finally Puts Forward Some Specific Application Countermeasures of Ethnic Elements. 1. Introduction Intangible cultural heritage is a valuable spiritual wealth left in the long history, which has a very high inheritance value. However, due to the lack of inheritance carrier and the change of social environment, many intangible cultural heritage is facing the crisis of loss. In view of this situation, by applying the representative ethnic elements to the popular dynamic visual communication design process, we can realize the innovation goal of inheritance carrier and give full play to the artistic and cultural value of intangible cultural heritage. 2. The Relationship between Intangible Cultural Heritage and Dynamic Visual Communication Design Dynamic visual communication design is a new form of artistic expression, which has a very wide range of audience and is loved by the public.