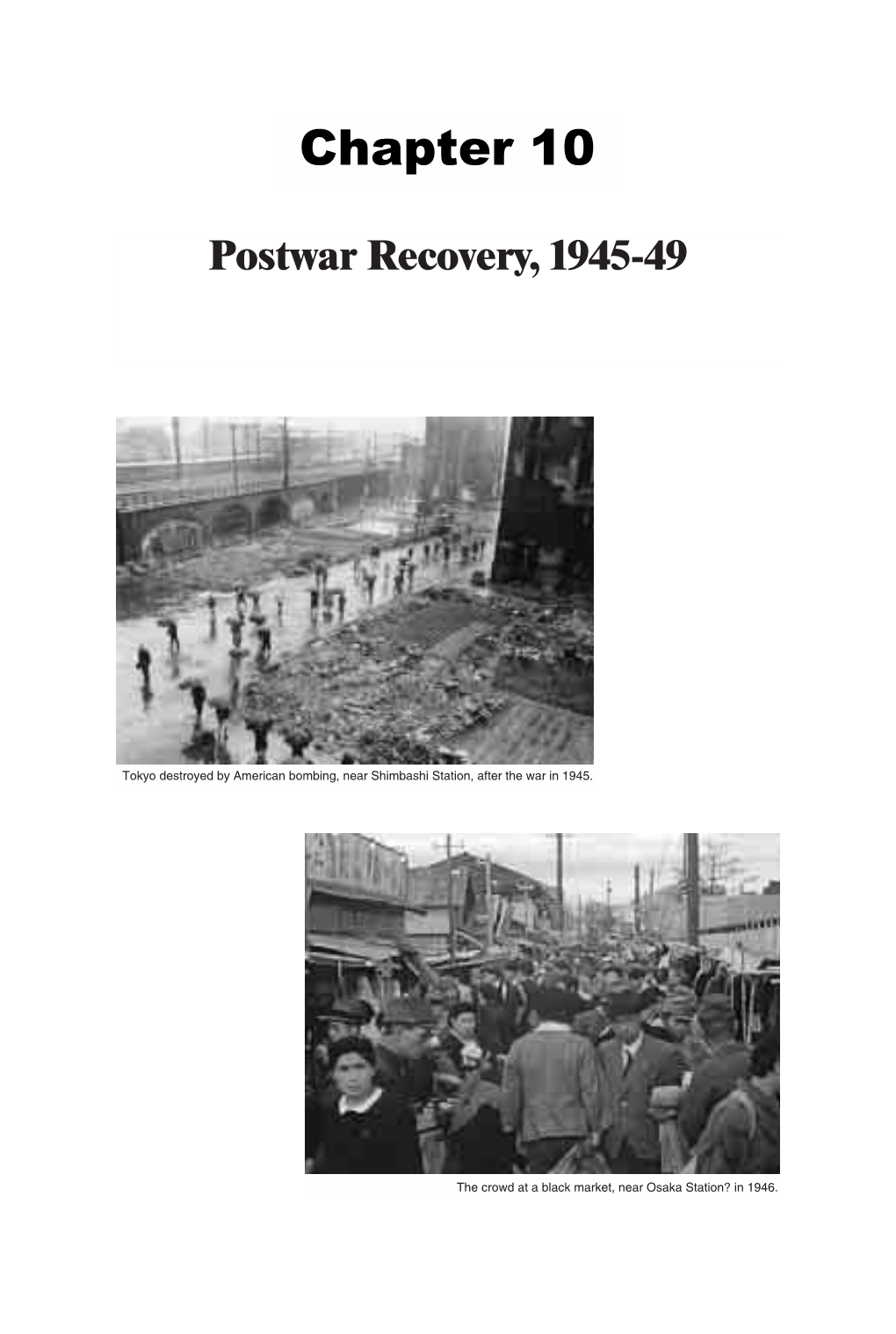

Postwar Recovery, 1945-49

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 1. Movements During the Pperiod from the Times When the Signs Appeared to May 1956 When Minamata Dsease Was Oficially Dscovered

CHAPTER 1. Movements during the Pperiod from the Times When the Signs Appeared to May 1956 when Minamata Dsease was Oficially Dscovered 1. Background of the times, positioning of Chisso in industrial policy, position of Chisso in economic society of the district, and characteristics of the technological development by Chisso (1) Situation of economy Industrial reconstruction in Japan was proceeded relatively from 1945 onward, early after World War II. Since around 1955, heavy chemical industrialization policy aiming at conversion of energy resources from coal to petroleum has been promoted, and the time when high economic growth of an annual rate of ca. 10% is achieved has arrived. The times of high economic growth lasted until 1973 when the primary oil shock occurred. In the times, Japan pushed on economic growth by the joint efforts of the Government and people with the national aim of increasing international economic competitive force. (2) Position of Chisso in the local economic society A. Location of Chisso in Minamata Minamata situated on the west side of Kyushu faces the Shiranui Sea (Yatsushiro Sea), and the Amakusa Islands are on the opposite shore of the sea. Minamata is adjacent to Kagoshima Prefecture on the most southern tip of Kumamoto Prefecture. The plain at the mouth of the River Minamata running in the center of the city is narrow, and there is a mountain close to the sea. Because of these situations, general traffic means was a sea-based route. In those days of 1898 before the invasion of Chisso, Minamata was a fishing and agrarian village of a total of 2,542 houses. -

Knowledge and Power in Occupied Japan: U.S. Censorship of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2018 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2018 Knowledge and Power in Occupied Japan: U.S. Censorship of Hiroshima and Nagasaki May E. Grzybowski Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018 Part of the Asian History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Grzybowski, May E., "Knowledge and Power in Occupied Japan: U.S. Censorship of Hiroshima and Nagasaki" (2018). Senior Projects Spring 2018. 134. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018/134 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Knowledge and Power in Occupied Japan: U.S. Censorship of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by May Grzybowski Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2018 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter One: Censorship Under SCAP………………………………………………………………..5 Chapter Two: Censored Texts…………………………………………………………..……….…....20 Chapter Three: Effects of Censorship………………………………………………………………...52 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………….66 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………...……69 Acknowledgements I would not have been able to finish this project without the support of many people. -

Overview of Mercury Issues in Japan

QQUUIIICCKKSSIIILLVVEERR FORUM JAPAN’S MINAMATA LEGACY AND THE NEED TO BAN ITS HG EXPORT Vol.1 No.1 May 2010 Japan and Mercury against the government, Kumamoto Prefecture, As the First UNEP Intergovernmental Negotiating and Chisso. Committee convenes in June 2010 and embarks on a 1987: The Kumamoto district court first recognized the monumental task of controlling mercury globally, an responsibility of the Government and Kumamoto understanding of how Japan, a country intimately linked Prefecture as well as Chisso. to the issue of mercury poisoning, handled the demands 1995: The government offered a “final political of Minamata victims and how it behaves globally on the solution” to address unrecognized victims, but issue of mercury is paramount. Does Japan’s past and did not acknowledge its responsibility. current rhetoric stand up to its responsibilities to the 2004: The Supreme Court of Japan denounced the victims and to the global community? inaction of the government and Kumamoto Prefecture regarding damage control. In 1932, Chisso Corporation opened an acetaldehyde 2005: More unrecognized victims sued Government, plant in Minamata, a small coastal community in Kumamoto Prefecture and Chisso. Kumamoto, Kyushu. Throughout its 36 years of 2009: The Minamata Relief Law was passed. The operation, methylmercury-containing wastewater was controversial law was criticized by some groups freely discharged into the bay, causing serious, for its inadequacies. intergenerational cases of mercury poisoning in 2010: The Kumamoto district court recommended a Minamata. settlement, which many of the victims accepted. The Japanese government has In order to end the half-a-century taken steps to repair the blemish Minamata saga, Government of Minamata over the years. -

Corporate Groups and Keiretsu in Japan

Japanese Yearbook on Business History-1991/8 Corporate Groups and Keiretsu in Japan Masahiro SHIMOTANI THE ISSUE Of several issues that have been discussed in Japan-U.S.Struc tural Impediments Initiatives talks since1989,attention has fo cused on Japan's keiretsu as being particularly important.Yet, when we look closely at the contents of those discussions,we find several conceptual confusions engendered still more confusion in the debate.One example of this can be seen in the way the•gsix large corporate complexes•hand•gcorporate groups•h(discussed below),two aggregates of completely different dimensions,are mixed up in discussions.Again,even though the term•gkeiretsu has a double-faceted meaning,that of expressing,in •h regard to var ious enterprise aggregates in Japan,1)the properties of relation ships between firms,and2)the structural aspect that is the foundation of those relationships,it would seem that debate has hitherto proceeded with complete indifference to such a distinc tion.There is,therefore,a need for these confusions to be cor rected as quickly as possible,if constructive discussion is to go ahead. Furthermore,when discussing such corporate aggregates and keiretsu in Japan,it is also necessary to make perfectly clear their historical formation processes and their places in history.Numer 4JAPANESE YEARBOOKON BUSINESS HISTORY-1991/8 ous analyses of corporate aggregates and keiretsu,dealing with their states at different times,have been amassed in Japan.Yet few of them represent studies incorporating a consistent examination -

Annual Report 2007 Annual Report 2007 Basic Credo of the Asahi Kasei Group

Annual Report 2007 Annual Report 2007 Basic Credo of the Asahi Kasei Group Basic tenets We the Asahi Kasei Group, through constant innovation and advances based in science and the human intellect, will contribute to human life and human livelihood. Guiding precepts We will create new value, thinking and working in unison with the customer, from the perspective of the customer. We will respect the employee as an individual, and value teamwork and worthy endeavor. We will contribute to our shareholders, and to all whom we work with and serve, as an international, high earnings enterprise. We will strive for harmony with the natural environment and ensure the safety of our products, operations, and activities. We will progress in concert with society, and honor the laws and standards of society as a good corporate citizen. Contents The Asahi Kasei History .................................................................................................................. 01 Consolidated Financial Highlights ................................................................................................. 04 To Our Shareholders ....................................................................................................................... 05 Driving the Strategic Advance: Growth Action – 2010 ................................................................... 06 Asahi Kasei Group Operations, Worldwide ................................................................................... 12 At a Glance ..................................................................................................................................... -

橡 7-Minamata Disease

Minamata Disease and Water Pollution Control Location: Minamata City, Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan Time Frame: 1956-1990 Programme/Project Status: completed Background: In 1959, at Minamata City, where the key industry was fishery, many unknown symptom cases with central nerve system disorder were reported. This disease was caused by methyl mercury and other toxic substance, contained in effluent to Minamata Bay from Chisso Co. Ltd. (chemical products industry, e.g. for acetaldehyde, ammonium etc.) when they were taken into human body through seafood and concentrated by the way of food chains. Although many serious cases were found, due to the lack of scientific information and technological capacity, as well as legal, administrative and social arrangements, as being the first major pollution-related disease in Japan, the counter-efforts including environmental recovery, remedies for patients were delayed. After 40 years it was finally completed to get rid of pollutant substance from the area. However, the case of Minamata Disease and Water Pollution Control may be an example for those environmental recovery efforts without any pre-existing arrangements. Also, the development of environment recovery technology and concurring tremendous investment should be emphasized, as well as notional and local government supports. Measures taken: Although the counter -measures were taken at late stage after tremendous tragedy, along with national legislation and administration development, many efforts were made. The measures taken in this case can be divided into 5 categories: a) research activities, b) regulatory, administrative, and legal arrangements, c) medical remedies for those suffered from disease, d) improvement of mercury emission system, and f) environment recovery efforts. -

Brief Chronology of Minamata Disease Incident

Brief Chronology of Minamata Disease Incident Year Event 1889 Official designation of Minamata Village (population: 12,040 ) 1908 Nippon Nitrogen Fertilizer Co., Ltd. (at present Chisso Co., Ltd.) builds a factory in Minamata. 1932 Chisso starts discharging methyl mercury, which was the causative substance of Minamata disease, to Minamata Bay. (Mercury was used to make acetaldehyde, which is used for vinyl, and mercury was drained with industrial wastewater.) 1949 Minamata Village becomes Minamata City (population: 42,270 ) 1956 A disease of unknown cause (Minamata disease) is discovered. (The official recognition date of Minamata disease : May 1st, 1956) The administration suspects the disease is infectious, so they disinfect the patients’ houses. The population reaches a peak at 50,461 people. 1957 Minamata Public Health Center and Kumamoto University undertake experiments on cats. A cat develops Minamata disease after being fed fish from Minamata Bay. Kumamoto Prefecture calls on the people not to eat fish and shellfish in Minamata Bay. 1959 Kumamoto University research group announces “Minamata disease is caused by consuming fish and shellfish from Minamata Bay. It is strongly suspected that mercury is the causative agent.” Chisso begins experiments with cats by feeding factory wastewater, and a cat shows symptoms, although it is not revealed. Patients’ families conclude “sympathy money contract” with Chisso, which states 300,000 yen should be paid for the deceased. 1968 Chisso stops producing acetaldehyde and discharging methyl mercury. (Chisso had polluted Minamata Bay and the Shiranui Sea since 1932 for 36 years.) The Japanese government affirms that Minamata disease is a pollution-triggered disease caused by Chisso Minamata Factory’s wastewater. -

Hisashi Yokoyama

SPRINGER BRIEFS IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE Hisashi Yokoyama Mercury Pollution in Minamata SpringerBriefs in Environmental Science SpringerBriefs in Environmental Science present concise summaries of cutting- edge research and practical applications across a wide spectrum of environmental fields, with fast turnaround time to publication. Featuring compact volumes of 50 to 125 pages, the series covers a range of content from professional to academic. Monographs of new material are considered for the SpringerBriefs in Environmental Science series. Typical topics might include: a timely report of state-of-the-art analytical techniques, a bridge between new research results, as published in journal articles and a contextual literature review, a snapshot of a hot or emerging topic, an in-depth case study or technical example, a presentation of core concepts that students must understand in order to make independent contributions, best practices or protocols to be followed, a series of short case studies/debates highlighting a specific angle. SpringerBriefs in Environmental Science allow authors to present their ideas and readers to absorb them with minimal time investment. Both solicited and unsolicited manuscripts are considered for publication. More information about this series at http://www.springernature.com/series/8868 Hisashi Yokoyama Mercury Pollution in Minamata Hisashi Yokoyama Educational Unit for Studies of Hills, Humans and Oceans Kyoto University Kyoto, Japan ISSN 2191-5547 ISSN 2191-5555 (electronic) SpringerBriefs in Environmental Science ISBN 978-981-10-7391-5 ISBN 978-981-10-7392-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-7392-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017960830 © The Author(s) 2018. This book is an open access publication. -

Noguchi Jun and Nitchitsu: Colonial Investment Strategy of a High Technology Enterprise Barbara Molony Santa Clara University, [email protected]

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons History College of Arts & Sciences 11-20-1989 Noguchi Jun and Nitchitsu: Colonial Investment Strategy of a High Technology Enterprise Barbara Molony Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/history Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Molony, B. (1989). Noguchi Jun and Nitchitsu: Colonial Investment Strategy of a High Technology Enterprise. In W. D. Wray (Ed.) Managing Japanese Enterprise: Cases from Japan's Prewar Experience. Cambridge, MA: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University. Copyright 1989 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Do not reproduce. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright 1989 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Do not reproduce. CHAPTER SEVEN Noguchi Jun and Nitchitsu: Investment Strategy of a High:J'echnology Enterprise BARBARA MOLONY In 1868, as the Meiji period (1868-1912) began, Japan's countryside was largely untouched by the technologies then rapidly developing in the West. In little more than a century, Japan has become an arche typal high-technology society and economy. The course of Japan's technological development was, of course, radically affected by World War II and its aftermath, but its basic contours were already evident before the war. By then, the defining characteristics of a tech nologically advanced society and economy were underway. -

Minamata Disease Municipal Museum

Minamata disease is a disease caused by pollution, which caused methyl mercury poisoning among Minamata Disease Municipal Museum people who consumed seafood contaminated by methyl mercury in industrial wastewater discharged to the Shiranui Sea by Chisso Minamata Factory. We are conveying the lessons of Minamata disease to the world. In 1956, the occurrence of a disease of unknown cause was reported in Minamata City. The aim of the Minamata Disease Municipal Museum is collecting and preserving valuable materials about However, even after the factory's industrial wastewater had been suspected as the cause, Minamata disease, which is considered as one of the earliest pollution problems in Japan, and handing down the wastewater continued to be discharged. As the result, the victims of Minamata disease were lessons and experiences of Minamata disease to future generations so they do not fade away. In order to prevent discovered widely in areas along the Shiranui Sea. It was when the Japanese economy was the reoccurrence of disastrous pollution like Minamata disease, through displays and storytellers, we exhibit and expanding rapidly. The sea in Minamata was so abundant in fishery resources that people called it tell the history and present situation of Minamata disease and the hard situations that patients experienced, such as the suffering and discrimination. “the sea that fish gush out”. People used to live a peaceful life with such bounties of the sea, but Since its opening in January 1993, 700,000people from within Japan and from over 175 foreign countries have they were suddenly struck by a disease of unknown cause and died off without receiving visited us to learn about pollution, the environment and human rights. -

Mercury in Japan 5

Draft Mercury Issues in Japan May 11, 2010 Version Takeshi Yasuma Citizens Against Chemicals Pollution (CACP) 1 Mercury Issues in Japan Contents 1. Overview of Mercury Issues in Japan 2. Minamata Disease 3. Campaign for Japan‟s Mercury Export Ban 4. Some Data for Mercury in Japan 5. Whale-eating Town, Taiji 2 Overview of Mercury Issues in Japan 1. There is no primary mercury mining since 1974. 2. There is no mercury-based chlor-alkali plant since 1999. 3. More than 100 ton/year of mercury is recycled from mercury containing products and by-products form smelters 4. About 13 ton/year of mercury is used for production of mercury containing devices. 5. More than 100 ton/year of mercury is exported. 6. Japan has a experience of serious methylmercury poisning incidents in Minamata and Niigata 3 Minamata Disease Minamata and Niigata Image: Niigata Prefecture, 2007 4 Minamata Disease Photo by W. Eugene Smith © Aileen M. Smith Courtesy of Ms. Aileen M. Smith http://aileenarchive.or.jp/aileenarchive_en/index.html 5 Minamata Disease Summary (1) What Happened in Minamata during 1932 to 2010? 1932-1968: Chisso operated acetaldehyde plant in Minamata using Inorganic mercury as a catalyst. Methylmercury was released to MInamata Bay 1950s: Sufferers emerged among residents around Minamata Bay. 1956: Minamata Disease was officially confirmed. But the cause was unknown. 1968: Government and Chisso recognized the methylmercury from Chisso as the cause of Minamata Disease and Chisso closed the acetaldehyde plant. 1969: Government offered a settlement, but victims were split into two groups. 1969-89: Many victims took Chisso to court for responsibility and compensation. -

Mitsuhiko Kimuracolonial Development of Modern Industry In

Mitsuhiko Kimura Colonial Development of Modern Industry in Korea, 1910-1939/40* Mitsuhiko Kimura** Abstract Under Japanese rule, the Korean economy underwent momentous change, so much so that, from a global perspective, it constituted an exceptional case in the first half of the 20th century. Between 1912 to 1939, traditional primary industry (mostly agriculture) shrank from about 70% to about 40% of GDP, meanwhile, the proportion of mining and manufacturing industries combined in the total economy grew signicantly, from about 5% to about 20%. In short, it represented a rapid transition from a primarily agricultural economy to a primarily non-agricultural one. During this transition, the agricultural sector itself underwent change. The policies of the Government-General and the development of the money economy led to improved farming techniques and changes in crop selection. Overall agricultural production increased steadily. In the meantime, industrialization in Korea began with small and medium-sized plants that simply processed raw materials. Then, as early as the 1910s, modern industries arose, particularly ironmaking plants. From the 1920s until 1930s, a private-sector enterprise built a large-scale chemical industrial complex founded on development of power plants. What must be emphasized here is that the colonized people themselves contributed widely to industrialization in Korea. Koreans positively responded to external stimulus and took the initiative in following Japanese models and learning skills in business and industrial technologies, thereby demonstrating entrepreneurship of their own. orea lacked modern industry when it was annexed by Japan. How did the Korean economy change under Japanese rule? Changes in Korea’s industrial structure clearly indicate economic transformation.