Article Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protecting Activists from Abusive Litigation: Slapps in the Global

PROTECTING ACTIVISTS FROM ABUSIVE LITIGATION SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH AND HOW TO RESPOND SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH Features and Policy Responses Author: Nikhil Dutta, Global Programs Legal Advisor, ICNL, [email protected]. Our thanks go to the following colleagues and partners for valuable discussions and input on this report: Abby Henderson; Charlie Holt; Christen Dobson; Ginna Anderson; Golda Benjamin; Lady Nancy Zuluaga Jaramillo; Zamira Djabarova; the Cambodian Center for Human Rights; iProbono; and SEEDS for Legal Initiatives. Published in July 2020 by the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL) TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL NORTH 2 III. SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH 4 A. Instances of Reported SLAPPs in the South 4 i. Thailand 5 ii. India 7 iii. Philippines 10 iv. South Africa 12 v. Other Instances of Reported SLAPPS in the South 13 B. Features of Reported SLAPPs in the South 15 IV. POLICY RESPONSES TO SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL NORTH 19 A. Enacting Protections for Public Participation 19 B. Creating Expedited Dismissal Procedures for SLAPPs 20 C. Endowing Courts with Supplemental Authorities to Manage SLAPPs 23 D. Permitting Recovery of Costs by SLAPP Targets 24 E. Authorizing Government Intervention in SLAPPs 25 F. Establishing Public Funds to Support SLAPP Defense 25 G. Imposing Compensatory and Punitive Damages on SLAPP Filers 25 H. Levying Penalties on SLAPP Filers 26 I. Reforming SLAPP Causes of Action 27 V. POLICY RESPONSES TO SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH 27 A. Thailand 28 B. Philippines 30 C. Indonesia 33 VI. DEVISING FUTURE RESPONSES TO SLAPPS IN THE GLOBAL SOUTH 33 REFERENCES 37 I. -

Free Speech Savior Or Shield for Scoundrels: an Empirical Study of Intermediary Immunity Under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act

Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review Volume 43 Number 2 Article 1 1-1-2010 Free Speech Savior or Shield for Scoundrels: An Empirical Study of Intermediary Immunity under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act David S. Ardia Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David S. Ardia, Free Speech Savior or Shield for Scoundrels: An Empirical Study of Intermediary Immunity under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, 43 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 373 (2010). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol43/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREE SPEECH SAVIOR OR SHIELD FOR SCOUNDRELS: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF INTERMEDIARY IMMUNITY UNDER SECTION 230 OF THE COMMUNICATIONS DECENCY ACT David S. Ardia * In the thirteen years since its enactment, section 230 of the Communications Decency Act has become one of the most important statutes impacting online speech, as well as one of the most intensely criticized. In deceptively simple language, its provisions sweep away the common law's distinction between publisher and distributor liability, granting operators of Web sites and other interactive computer services broad protectionfrom claims based on the speech of third parties. Section 230 is of critical importance because virtually all speech that occurs on the Internet is facilitated by private intermediaries that have a fragile commitment to the speech they facilitate. -

Slapped: a Tool for Activists

Published May 2014 SLAPPed: A Tool for Activists The right to speak your mind and fight for what you believe in without – or in spite of – reprisal, is one of our nation’s oldest and dearest principles. But for just as long, there have been powerful forces that prefer it when people simply stay silent. Whether the year is 2014 or 1814, these forces have always proved willing to use whatever tools they can muster to silence their critics. Often, they turn to the legal system, where their superior resources can help them make life very difficult for those who dare to challenge them. As these legal tactics have evolved, they have been a given a name. Today we call them Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation, or SLAPP suits. Their goal is not victory in the courtroom. It’s much simpler than that. Their goal is to send this very clear message: “Exercise your First Amendment rights at your own peril.” This message represents the polar opposite of everything the American Civil Liberties Union stands for. We have little concern for the ever-evolving partisan disagreements and economic realities that prompt these SLAPP suits. Our stake in this issue is much larger. Our court system should be a place where we are all treated equally in the eyes of the law. It should not be a place where the powerful use their abundance of resources to enact revenge on those who see the world through different eyes. What future is there for freedom of speech if we allow those who speak out to be bled dry and turned into an example of what happens when you stand up to speak your mind? 1 SLAPP suits pervert our legal system by turning it into a war of attrition, a place where who is right and who is wrong does not matter nearly as much as who has the most resources. -

International Annual Report 2020 Defending Freedom of Expression and Information Around the World International Women’S Day Protest in Mexico City on 8 March 2020

International Annual Report 2020 Defending Freedom of Expression and Information around the World International Women’s Day protest in Mexico City on 8 March 2020. Among other demands, protesters called for justice for the more than 10 women murdered daily in Mexico and the decriminalisation of abortion. (Photo: ARTICLE 19 Mexico & Central America) 2 ARTICLE 19 Contents Civic Space Digital 6 From the Executive Director: 37 Huge step forward for the right 43 Artificial intelligence: A Global Quinn McKew to protest worldwide South perspective 7 From the Chair of the Board: 39 Combating “hate speech” 43 Working with dating apps Paddy Coulter worldwide to protect the LGBTQI+ community 8 Viral lies: Misinformation 40 Holistic protection of journalists and COVID-19 and civil society in Kenya, 45 Lawsuit against facial Malawi, and Myanmar recognition in São Paulo 9 A global response to a subway global crisis 41 Research uniting civil society in the Middle East and North 46 Assessing the human rights 12 “It’s all about prioritising Africa impacts of Internet registries wellbeing”: Supporting our staff through the pandemic 13 Reporting on the pandemic 14 Global Expression Report 2019/2020: Most people now live in a freedom of expression crisis 16 Researching rights 18 Law and policy 22 International advocacy 28 Freedom of expression: A tool to achieve women’s equality 32 Campaign updates 34 Building capacity, enhancing safety: Training and workshops International Women’s Day protest in Hundreds of people protest on 8 February Supporter of Net Neutrality Lance Brown Mexico City on 8 March 2020. Among other 2020 in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in repudiation of Eyes protests the Federal Communications demands, protesters called for justice for gender violence and in memory of those Commission’s decision to repeal the the more than 10 women murdered daily who died because they were women. -

© 2021 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Original U.S. Government Works. 1 FREE SPEECH in the MODERN AGE, 31 Fordham Intell

FREE SPEECH IN THE MODERN AGE, 31 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 978 31 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 978 Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Summer, 2021 Symposium Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journala1 Copyright © 2021 by Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal FREE SPEECH IN THE MODERN AGE I. Banned Books: Prepublication Review in the Intelligence Community 978 II. Hitting Back: SLAPP Suits & Anti-SLAPP Statutes 984 III. Keynote Speech: Public Square 2.0: Free Speech on the Internet 988 IV. Celebrity Paradox: Copyright, Social Media & Paparazzi Photography 992 I. Banned Books: Prepublication Review in the Intelligence Community Moderated by Abner S. Greene,1 the Banned Books: Prepublication Review in the Intelligence Community Panel discussed the tension between national intelligence agencies' prepublication review process and employees' First Amendment interests related to *979 classified information. Particularly, this panel focused on how nondisclosure agreements (“NDAs”) signed by current or former national intelligence employees affected the publication of books written by high-profile government officials. For example, memoirs written by former U.S. National Security Advisor John R. Bolton2 and former CIA employee Edward Snowden3 not only drew public attention, but also prompted lawsuits by the U.S. Department of Justice alleging violations of NDAs.4 These government NDAs require current and former national intelligence employees to submit any public statements or publications to the federal government for review prior to publication. The panel also discussed how to balance national security interests and the public's access to information. Panelists included Dr. Christopher E. -

A SLAPP in the Facebook: Assessing the Impact of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation on Social Networks, Blogs and Consumer Gripe Sites

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 21 Issue 2 Spring 2011 Article 2 A SLAPP in the Facebook: Assessing the Impact of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation on Social Networks, Blogs and Consumer Gripe Sites Robert D. Richards Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation Robert D. Richards, A SLAPP in the Facebook: Assessing the Impact of Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation on Social Networks, Blogs and Consumer Gripe Sites, 21 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 221 (2011) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol21/iss2/2 This Lead Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Richards: A SLAPP in the Facebook: Assessing the Impact of Strategic Lawsui A SLAPP IN THE FACEBOOK: ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF STRATEGIC LAWSUITS AGAINST PUBLIC PARTICIPATION ON SOCIAL NETWORKS, BLOGS AND CONSUMER GRIPE SITES Robert D. Richards' I. INTRODUCTION Until April 5, 2010, Justin Kurtz was just another college student with an axe to grind and a Facebook page on which to grind it.2 On that spring day, however, he became the target of a $750,000 lawsuit by a towing company he claims damaged his car and illegally removed a parking decal, resulting in a $118 fee.' Rather than airing his complaints in court or to a consumer protection agency, Kurtz posted his grievances on a Facebook group he created called "Kalamazoo Residents Against T & J Towing."' Within two days, the Western Michigan University student had attracted 800 online followers, some of whom weighed in with "comments about their own maddening experiences with 1. -

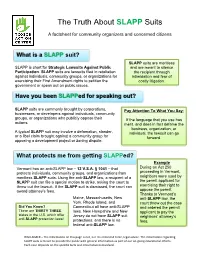

The Truth About SLAPP Suits

The Truth About SLAPP Suits A factsheet for community organizers and concerned citizens What is a SLAPP suit? SLAPP suits are meritless SLAPP is short for Strategic Lawsuits Against Public and are meant to silence Participation. SLAPP suits are lawsuits filed in retaliation the recipient through against individuals, community groups, or organizations for intimidation and fear of exercising their First Amendment rights to petition the costly litigation. government or speak out on public issues. Have you been SLAPPed for speaking out? SLAPP suits are commonly brought by corporations, Pay Attention To What You Say: businesses, or developers against individuals, community groups, or organizations who publicly oppose their If the language that you use has actions. merit, and does in fact defame the business, organization, or A typical SLAPP suit may involve a defamation, slander, individual, the lawsuit can go or a libel claim brought against a community group for forward. opposing a development project or zoning dispute. What protects me from getting SLAPP ed? Example Vermont has an anti -SLAPP law – 12 V.S.A. § 1041 – that During an Act 250 protects individuals, community groups, and organizations from proceeding in Vermont, meritless SLAPP suits. Using the anti- SLAPP law, a recipient of a neighbors were sued by SLAPP suit can file a special motion to strike, asking the court to the permit applicant for exercising their right to throw out the lawsuit. If the SLAPP suit is dismissed, the court can oppose the permit. award attorney’s fees. Thanks to Vermont’s Maine, Massachusetts, New anti -SLAPP law, the York, Rhode Island, and court threw out the case Did You Know? Connecticut all have anti-SLAPP and ordered the permit There are THIRTY THREE laws. -

Virtual Freedom

VIRTUAL FREEDOM VIRTUAL FREEDOM Net Neutrality and Free Speech in the Internet Age Dawn C. Nunziato STA NF ORD LAW BOOKS An Imprint of Stanford University Press Stanford, California Stanford University Press Stanford, California ©2009 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any informa- tion storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nunziato, Dawn C. Virtual freedom : net neutrality and free speech in the Internet age / Dawn C. Nunziato. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8047-5574-0 (cloth : alk. paper)—isbn 978-0-8047-6385-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Freedom of speech—United States. 2. Internet—Censorship—United States. 3. Internet—Law and legislation—United States. I. Title. KF4772.N86 2009 342.7308'53—dc22 2009012532 Designed by Bruce Lundquist Typeset by Classic Typography in 10/14 Minion To my wonderful children, Allie and Zach— may you always be free to express yourselves to my husband, Jon, my favorite author—for leading the way and to my parents, Frances and Joseph—for always believing in me “[W]e could be witnessing the beginning of the end of the Internet as we know it.” — Michael J. Copps, FCC commissioner, “The Beginning of the End of the Internet?” New America Foundation, Washington, D.C., October 9, 2003 “The potential for abuse of this private power over a central avenue of communication cannot be overlooked. -

Targeting the Texas Citizen Participation Act: the 2019 Texas Legislature's Amendments to a Most Consequential Law

St. Mary's Law Journal Volume 52 Number 1 Article 1 10-20-2020 Targeting the Texas Citizen Participation Act: The 2019 Texas Legislature's Amendments to a Most Consequential Law Amy Bresnen BresnenAssociates, Inc. Lisa Kaufman Davis Kaufman, PLLC Steve Bresnen BresnenAssociates, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/thestmaryslawjournal Part of the Civil Law Commons, Civil Procedure Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Remedies Commons, Legislation Commons, Litigation Commons, Public Law and Legal Theory Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Amy Bresnen, Lisa Kaufman & Steve Bresnen, Targeting the Texas Citizen Participation Act: The 2019 Texas Legislature's Amendments to a Most Consequential Law, 52 ST. MARY'S L.J. 101 (2020). Available at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/thestmaryslawjournal/vol52/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the St. Mary's Law Journals at Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. Mary's Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bresnen et al.: Targeting the Texas Citizen Participation Act ARTICLE TARGETING THE TEXAS CITIZEN PARTICIPATION ACT: THE 2019 TEXAS LEGISLATURE’S AMENDMENTS TO A MOST CONSEQUENTIAL LAW AMY BRESNEN* LISA KAUFMAN** STEVE BRESNEN*** No one else was in the room where it happened. No one really knows how the game is played, the art of the trade how the sausage gets made. -

Free Speech in the Modern Age [email protected]

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 31 XXXI Number 4 Article 1 2021 Free Speech in the Modern Age [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Civil Law Commons, Common Law Commons, Communications Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation [email protected], Free Speech in the Modern Age, 31 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 978 (2021). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol31/iss4/1 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Free Speech in the Modern Age Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal* I. BANNED BOOKS: PREPUBLICATION REVIEW IN THE INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY.......................................... 978 II. HITTING BACK: SLAPP SUITS & ANTI-SLAPP STATUTES ..................................................................... 984 III. KEYNOTE SPEECH: PUBLIC SQUARE 2.0: FREE SPEECH ON THE INTERNET ............................................. 988 IV. CELEBRITY PARADOX: COPYRIGHT, SOCIAL MEDIA & PAPARAZZI PHOTOGRAPHY ....................................... 992 I. BANNED BOOKS: PREPUBLICATION REVIEW IN THE INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY Moderated by Abner S. Greene,1 the Banned Books: Prepubli- cation Review in the Intelligence Community Panel discussed the tension between national intelligence agencies’ prepublication re- view process and employees’ First Amendment interests related to * These summaries are brought to you by the staff and editors of the Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal, Volume XXXI. -

The First Amendment SLAPPS Back: an Overview of the Free-Speech Protections of Kansas' New Anti-SLAPP Statute

the first amendment slapps back The First Amendment SLAPPS Back: An Overview of the Free-Speech Protections of Kansas' New Anti-SLAPP Statute By Eric Weslander 30 The Journal of the Kansas Bar Association the first amendment slapps back Introduction ne not need look far in today’s world for prominent examples of threats of dubious legal action against journalists, in retaliation for unflattering reports on the rich and powerful. Examples include an attorney for movie producer Harvey Weinstein threat- Oening to sue the New York Times over reports of sexual-harassment complaints,1 or an attorney for unsuccessful Alabama U.S. Senate candidate Roy Moore writing that a local news organi- zation should be liable on grounds it “intentionally refused to advance the truth” regarding the sexual-misconduct allegations against Moore, and should be liable for “oppression, fraud, wanntonness, and/or malice.”2 A Kansas statute enacted in 2016 that has garnered relatively little public attention, K.S.A. 60-5320, the “Public speech protection act,” represents the latest in step in a nationwide battle to fight meritless lawsuits that chill free speech, known as SLAPPs, or “strategic lawsuits against public participation.” Familiarity with this statute— which provides for mandatory attorneys’ fees in the event of a successful anti-SLAPP motion — is a must for attorneys litigating civil matters in Kansas courts. In essence, the statute allows a defendant to bring a special motion to strike a claim early in litigation, if that claim is “based on, relates to or is in response to a party’s exercise of the right of free speech, right to petition, or right of association,” as exten- sively defined in the statute, shifting the burden to the plaintiff to show that it has a prima facie case. -

Freedom of Expression and the Information Society: a Legal Analysis Toward a Libertarian Framework for Libel

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND THE INFORMATION SOCIETY: A LEGAL ANALYSIS TOWARD A LIBERTARIAN FRAMEWORK FOR LIBEL DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nikhil Moro, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Prabu David, Advisor Professor Elliot Slotnick Professor David Goldberger ________________________ Professor Sharon West Advisor Professor Young Mie Kim Graduate Program in Communication ABSTRACT Web blogs, as alternate sources of political opinion and analysis, have enabled new voices that can empower netizens and democratize information access. Their larger social contribution may be that they increase manifold the ideas available in the marketplace, in theory challenging any information hegemony of an increasingly consolidating corporate media. Bloggers, citizen journalists and others of the fifth estate have joined the social conversation by acting as watchdogs of not just government but also of the corporate media. Libel law, as a determinant of freedom of expression, also defines the democratic values of individual self-fulfillment, marketplace of ideas, and empowerment. Libel lawsuits, however, impose a chilling effect, a chill which is exacerbated for the fifth estate by the challenge of multiple personal jurisdictions – a netizen can be hauled before a court whose location, laws and procedures are hard to predict. The dissertation addresses that express challenge by proposing a separate common jurisdiction for libel cases that emanate in the information society. Specifically, it delineates a normative, inductive, theoretical framework for that common jurisdiction after analyzing the fundamental principles of freedom of expression characterizing jurisprudence.