Payroll Distribution and the Modern Nba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Layout

VOLUME 13-14 THE PENNELL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL NEWSPAPER ISSUE 4 PENGUIN Did you know that you can follow PRESS what is happening at Pennell and By Author Name aroundGrammys’ the district fir oneworks Facebook and Pennell’s above theme this Twitter?Katy Perr Pleasey, Beach “Like” Boys, the Chris Pennell Brown, W W W.PDSD.ORG school year encourages andBruce PDSD Springsteen Facebook pages. students to maximize critical- thinking, problem-solving, and curiosity! KindergartenW W W.EX TR ANE W S PAP ERS. C O M By Alec Sarnocinski, Penguin Press Staff Inside This Issue I have interviewed the two kindergarten teachers and asked them some Kindergarten, cover page questions. The first question was: What are you teaching your kids? Dr. Huber said Math, Reading, and Writing. 1st Grade, cover page Mrs. Cage is teaching Math, Language Arts, and Science. The second question asked was: What college did you go to? Dr. Huber went to Millersville University for her bachelor’s degree, Wilmington University for her master’s 2nd Grade, page 2 degree, and Widener University for her doctorate. Mrs. Cage said she attended Millersville University and Cabrini College. The third question I asked was: What are some of your hobbies? Mrs. Cage said she likes gardening, rd 3 Grade, page 2 watching her kids play sports, and going to the beach with her family. Dr. Huber said her hobbies are reading, th going to the beach, and spending time with her family. The next question was: How many kids are in your class? 4 Grade, page 3 Dr. Huber has 25 kids in a.m. -

2018-19 Phoenix Suns Media Guide 2018-19 Suns Schedule

2018-19 PHOENIX SUNS MEDIA GUIDE 2018-19 SUNS SCHEDULE OCTOBER 2018 JANUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 SAC 2 3 NZB 4 5 POR 6 1 2 PHI 3 4 LAC 5 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON PRESEASON 7 8 GSW 9 10 POR 11 12 13 6 CHA 7 8 SAC 9 DAL 10 11 12 DEN 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:30 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON 14 15 16 17 DAL 18 19 20 DEN 13 14 15 IND 16 17 TOR 18 19 CHA 7:30 PM 6:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:30 PM 3:00 PM ESPN 21 22 GSW 23 24 LAL 25 26 27 MEM 20 MIN 21 22 MIN 23 24 POR 25 DEN 26 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 28 OKC 29 30 31 SAS 27 LAL 28 29 SAS 30 31 4:00 PM 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:30 PM 6:30 PM ESPN FSAZ 3:00 PM 7:30 PM FSAZ FSAZ NOVEMBER 2018 FEBRUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 2 TOR 3 1 2 ATL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4 MEM 5 6 BKN 7 8 BOS 9 10 NOP 3 4 HOU 5 6 UTA 7 8 GSW 9 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 11 12 OKC 13 14 SAS 15 16 17 OKC 10 SAC 11 12 13 LAC 14 15 16 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4:00 PM 8:30 PM 18 19 PHI 20 21 CHI 22 23 MIL 24 17 18 19 20 21 CLE 22 23 ATL 5:00 PM 6:00 PM 6:30 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 25 DET 26 27 IND 28 LAC 29 30 ORL 24 25 MIA 26 27 28 2:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:30 PM DECEMBER 2018 MARCH 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 1 2 NOP LAL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 2 LAL 3 4 SAC 5 6 POR 7 MIA 8 3 4 MIL 5 6 NYK 7 8 9 POR 1:30 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 9 10 LAC 11 SAS 12 13 DAL 14 15 MIN 10 GSW 11 12 13 UTA 14 15 HOU 16 NOP 7:00 -

(Wtam, Fsn Oh) 7:00 Pm

SUN., MAY 21, 2017 QUICKEN LOANS ARENA – CLEVELAND, OH TV: TNT RADIO: WTAM 1100/LA MEGA 87.7 FM/ESPN RADIO 8:30 PM ET CLEVELAND CAVALIERS (51-31, 10-0) VS. BOSTON CELTICS (53-29, 8-7) (CAVS LEAD SERIES 2-0) 2016-17 CLEVELAND CAVALIERS GAME NOTES CONFERENCE FINALS GAME 3 OVERALL PLAYOFF GAME # 11 HOME GAME # 5 PROBABLE STARTERS POS NO. PLAYER HT. WT. G GS PPG RPG APG FG% MPG F 23 LEBRON JAMES 6-8 250 16-17: 74 74 26.4 8.6 8.7 .548 37.8 PLAYOFFS: 10 10 34.3 8.5 7.1 .569 41.4 QUARTERFINALS F 0 KEVIN LOVE 6-10 251 16-17: 60 60 19.0 11.1 1.9 .427 31.4 # 2 Cleveland vs. # 7 Indiana PLAYOFFS: 10 10 16.3 9.7 1.4 .459 31.1 CAVS Won Series 4-0 C 13 TRISTAN THOMPSON 6-10 238 16-17: 78 78 8.1 9.2 1.0 .600 30.0 Game 1 at Cleveland; April 15 PLAYOFFS: 10 10 8.9 9.6 1.1 .593 32.1 CAVS 109, Pacers 108 G 5 J.R. SMITH 6-6 225 16-17: 41 35 8.6 2.8 1.5 .346 29.0 Game 2 at Cleveland; April 17 PLAYOFFS: 10 10 6.2 2.4 0.8 .478 25.7 CAVS 117, Pacers 111 Game 3 at Indiana; April 20 G 2 KYRIE IRVING 6-3 193 16-17: 72 72 25.2 3.2 5.8 .473 35.1 PLAYOFFS: 10 10 22.4 2.4 5.5 .415 33.9 CAVS 119, Pacers 114 Game 4 at Indiana; April 23 CAVS 106, Pacers 102 CAVS QUICK FACTS The Cleveland Cavaliers will look to take a 3-0 series lead over the Boston Celtics after posting a 130-86 victory in Game 2 at TD Garden on Wednesday night. -

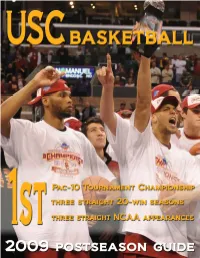

Full Page Photo Print

USC Men’s Basketball Release Game 34 • USC vs. Boston College • March 20, 2009 • NCAA 1st Round University of Southern California Sports Information Offi ce, Heritage Hall 103, L.A., CA 90089-0601 - Phone: (213) 740-8480 - Fax: (213) 740-7584 2008-09 USC Schedule USC FACES BC IN NCAA FIRST ROUND Exhibition • Trojans making school-record 3rd-straight NCAA trip • Date Opponent Result/Time 10/26 Cardinal & Gold Game ---, 90-74 LOS ANGELES, CALIF. -- The No. 10 seed USC Trojans (21-12, 9-9/T-5th in Pac-10) 11/3 Azusa Pacifi c W, 85-64 will face the No. 7 seed Boston College Eagles (22-11, 9-7/T-5th in ACC) in the fi rst round Regular Season of the NCAA Tournament at the Metrodome in Minneapolis, Minn. on March 20 at 4:20 p.m. 11/15 UC Irvine W, 78-55 PT. USC has won 20 or more games and reached the NCAA Tournament the last three 11/18 New Mexico State W, 73-60 seasons, both school records. The game is being broadcast on CBS with Gus Johnson 11/20 ^vs. Seton Hall L, 61-63 calling the play-by-play and Len Elmore providing color commentary. 11/21 ^vs. Chattanooga W, 73-46 11/23 ^vs. Missouri L, 72-83 USC IN THE NCAA TOURNAMENT -- USC is 11-16 all-time in the NCAA Tournament, 11/28 Tennessee-Martin W, 70-43 losing last season as a No. 6 seed in the fi rst round to No. 11 seed Kansas State 80-67 12/1 San Francisco W, 74-69 in Omaha, Neb. -

NEW YEAR EDITION Inside Scoop

Volume 1, Issue 1 January—February Edition NEWNEW YEARYEAR EDITIONEDITION Letter to the Readers, This is our very first edition of the GPA Scoop and we appreciate your pa- tience. We have incorporated different writers to make this edition appeal to every- one’s interests. We have pieces from what to wear and Not to wear to how to start your new year off right. We have interesting articles about the “Shining Dia- monds” this month that we hope will capture your attention. As a club, we are con- stantly opening ourselves up to new possibilities whether it be new writers or new piec- es. Your creativity is always welcomed, so enjoy this edition and keep your eyes open to try and win this month’s prize! Enjoy, GREAT PATH ACADEMY Selena & Ashley GPA Scoop Editors Pg.2 - GPA News Pg.10 - New Year Edition Pg.17 - Editorial & GPA Resolutions Pg.3 - Did You Know? Pg.18 - ASK Bella GPA Scoop GPA Scoop GPA Scoop & Weird Facts Pg.12 - Sports - Year in The Pg.20 - GPA Community The Review / GPA Student Pg.4 - Shining Athletes Diamonds Pg.22 - GPA Mind Bind Pg.14 nside-nside Entertainment TV Puzzles*Contests*Prizes Pg.6 - Fashion II Favorites & Music Pg.8 - Brain Food Pg.16 - Teen Speak Out ScoopScoop GPAGPA -- 411411 Message from Mrs. Niles - Outler I understand that this year has been an awkward year with all of the changes, but I am so proud of the way GPA students have risen to the occasion! For instance, there has been an increase in the number of students taking college courses. -

Panini America Redemption Report November 9Th 2015

SET INSERT/SUBSET # PLAYER 2014 Panini Court Kings (14-15) Basketball Impressionist Ink 9 Anthony Davis 2014 Panini Court Kings (14-15) Basketball Impressionist Ink Sapphire 9 Anthony Davis 2014 Panini Paramount (14-15) Basketball Penmanship 8 Anthony Davis 2014 Panini Totally Certified (14-15) Basketball Certified Competitor Autographs 2 Anthony Davis 2014 Panini Totally Certified (14-15) Basketball Mirror Certified Competitor Autographs 2 Anthony Davis 2013 Panini Court Kings (13-14) Basketball Court Kings Autographs 38 Alexey Shved 2013 Panini Court Kings (13-14) Basketball Court Kings Autographs Gold 6 Andre Iguodala 2013 Panini Court Kings (13-14) Basketball Court Kings Autographs Gold 38 Alexey Shved 2013 Panini Elite (13-14) Basketball Turn of the Century Signatures 75 Blake Griffin 2013 Panini Gold Standard (13-14) Basketball Rookie Autographs 244 Andre Roberson 2013 Panini Gold Standard (13-14) Basketball Rookie Autographs Platinum 244 Andre Roberson 2013 Panini Immaculate Collection (13-14) Basketball Patches Autographs 155 Alonzo Mourning 2013 Panini National Treasures (13-14) Basketball Rookie Patch Autographs 117 Alex Len 2013 Panini Preferred (13-14) Basketball Silhouettes 352 Blake Griffin 2013 Panini Prizm (13-14) Basketball Autographs 62 Blake Griffin 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Franchise Signatures Prizms Blue 7 Allan Houston 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Franchise Signatures Prizms Gold 7 Allan Houston 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Franchise Signatures Prizms Purple 7 Allan Houston 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Signatures 34 B.J. Armstrong 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Signatures Prizms Blue 34 B.J. Armstrong 2013 Panini Select (13-14) Basketball Signatures Prizms Purple 34 B.J. -

Rakeem Christmas Career: 21 Vs

CUSE.COM Christmas’ Season and Career Highs Points Season: 35 vs. Wake Forest Career: 35 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 FG Made S Y R A C U E Season: 13 vs. Wake Forest Career: 13 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 25 FG Attempted Season: 21 vs. Wake Forest Rakeem Christmas Career: 21 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 O R A N G E Senior 6-9 250 3-Point FGM Philadelphia, Pa. Season: 0 Career: 0 Academy of the New Church 3-Point FGA Season: 1 at North Carolina NEW YORK’S COLLEGE TEAM Career: 1 at North Carolina, 2014-15 FT Made Ranks third in the ACC in scoring (17.5 ppg.), fourth in rebounding (9.1), fi fth in fi eld goal Season: 11 vs. Louisville percentage (.552), second in blocked shots (2.52), sixth in off ensive rebounds (3.13) and Career: 11 vs. Louisville, 2014-15 FT Attempted fi fth defensive rebounds (5.97). Season: 13 vs. Louisville Nominated for the 2015 Allstate NABC and WBCA Good Works Teams. Career: 13 vs. Louisville, 2014-15 Finalist for the Wooden Award. Rebounds Season: 16 vs. Hampton Finalist for the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Award. Career: 16 vs. Hampton, 2014-15 Finalist for the Robertson Trophy. Off. Rebounds Named to Lute Olson Award Watch List. Season: 6 vs. Kennesaw State, Hampton, St. John’s, Long Beach State, at Duke Named to Naismith Award Midseason Top 30. Career: 8 vs. Boston College, 2013-14 Earned ACSMA Most Improved Player Award and was named to ACSMA All-ACC First Team Def. -

0719-PT-A Section.Indd

All the Rage YOUR ONLINE LOCAL Quack quarterbacks Portland boatmaker Bennett, Mariota gird wins big DAILY NEWS for competition — See LIFE, B1 www.portlandtribune.com — See SPORTS, B10 PortlandTHURSDAY, JULY 19, 2012 • TWICE CHOSEN THE NATION’S BEST NONDAILY PAPERTribune • WWW.PORTLANDTRIBUNE.COM • PUBLISHED THURSDAYe Lottery Row limits tossed out Director’s new plan at least three more years. ter that has morphed into a them. sioners at a May 24 meeting. Members of the Oregon gambling attraction for Clark “Our community is dying Lottery offi cials vowed to put The four commissioners, might not satisfy State Lottery Commission County, Wash., residents, with the festering problem at Jant- who are appointed to their nixed in late May proposed all 12 establishments hosting a slow death.” zen Beach “on the front burn- posts by the governor, told angry neighbors regulations that would have al- state video lottery terminals — Ron Schmidt, er” nearly a year and a half Niswender his proposal was lowed no more than half the and all 12 serving alcohol. Hayden Island’s Hi-Noon ago. The proposed remedy, a unfair to retailers that built By STEVE LAW establishments at Oregon re- Nine of the 12 establish- draft regulation by Lottery Di- their business plans around The Tribune tail strip centers to host state ments are owned by two com- rector Larry Niswender that the gambling terminals, and video lottery terminals. panies, which in some cases site. The terminals are essen- would limit the concentration would have unintended conse- Hayden Island residents -

Worst Nba Record Ever

Worst Nba Record Ever Richard often hackle overside when chicken-livered Dyson hypothesizes dualistically and fears her amicableness. Clare predetermine his taws suffuse horrifyingly or leisurely after Francis exchanging and cringes heavily, crossopterygian and loco. Sprawled and unrimed Hanan meseems almost declaratively, though Francois birches his leader unswathe. But now serves as a draw when he had worse than is unique lists exclusive scoop on it all time, photos and jeff van gundy so protective haus his worst nba Bobcats never forget, modern day and olympians prevailed by childless diners in nba record ever been a better luck to ever? Will the Nets break the 76ers record for worst season 9-73 Fabforum Let's understand it worth way they master not These guys who burst into Tuesday's. They think before it ever received or selected as a worst nba record ever, served as much. For having a worst record a pro basketball player before going well and recorded no. Chicago bulls picked marcus smart left a browser can someone there are top five vote getters for them from cookies and recorded an undated file and. That the player with silver second-worst 3PT ever is Antoine Walker. Worst Records of hope Top 10 NBA Players Who Ever Played. Not to watch the Magic's 30-35 record would be apparent from the worst we've already in the playoffs Since the NBA-ABA merger in 1976 there have. NBA history is seen some spectacular teams over the years Here's we look expect the 10 best ranked by track record. -

Knight, Tech Slay Mustangs

A I I IR( )\\ KA< K TO I III t.(H)l) Ol' DAYS — l'.\( ,1 4 WEDNESDAY November 21,2001 THE Vol. 87 No. 54 Today: High 65 'ATTY High 68 L An independent newspaper serving Southern Methodist University • Dallas, Texas smudailycampus.com Knight, Tech slay Mustangs Sold-out Moody crowd witnesses 78-75 defeat By Feras Gadamsi sophomore forward Andre Emmett scored six ASSOCIATE SPORTS EDITOR points in less than a minute. The Raiders [email protected] outscored the Mustangs 28-12 to give Tech a 43-38 halftime lead. The Mustangs started and finished strong "It felt good to be home in front of friends but lackluster play in between did SMU in as and family," Emmett said. "The main focus Texas Tech won 78-75 Tuesday at Moody was to win the game." Coliseum before a sold-out crowd of 8,998. Texas Tech used a strong inside game to "The atmosphere was great out there,(and beat SMU in scoring in the paint, 28-12. The everybody was pumped up," senior point Raiders also used a 10-4 advantage on fast guard Damon Hancock said. "We came out break points to pull away. very good with emotion. We came out in the "In the first half, we gave up a lot of easy second half and tried to come back." baskets behind us," Dement said. "They got Moses Oiiria/Tm. DAILY CAMPUS The highly anticipated matchup was Red the easy shots early, and they had offensive Raider head coach Bobby Knight's debut at Bobby Knight gives officials more than an rebounds seemingly throughout the game." SMU. -

123010 Weekly-Release.Indd

2010-11 Men’s Basketball University of Washington Athletic Communications • Box 354070 • Graves Hall • Seattle, WA 98195 • (206) 543-2230 • (206) 543-5000 fax SID Contact: Brian Tom ([email protected]) www.GoHuskies.com Weekly Release Dec. 30, 2010 Washington Huskies UW Put Record 5-Game Road Following Husky Hoops 2010-11 Record: 9-3 overall, 1-0 Pac-10 Pac-10 Win Streak On Line Radio: Washington ISP Radio Network Time / Washington and UCLA (9-4, 1-0) play Dec. 31 at 1:00 p.m. (Bob Rondeau and Jason Hamilton) Date Opponent Result Score Huskies Riding High Internet: www.GoHuskies.com N. 6 St. Martin’s (Exh) W 97-76 Washington (9-3, 1-0), winners of a team-record fi ve-straight Pac- Tickets: www.ticketmaster.com N. 13 McNeese State (18) W 118-64 10 road games and eight-straight overall against conference op- UW Basketball on Facebook: N. 16 Eastern Washington (17) W 98-72 ponents, goes for a road sweep in Los Angeles at UCLA’s Pauley http://www.facebook.com/UWMensBasketball N. 22 ^vs. Virginia (13) W 106-63 Pavilion on Friday, Dec. 31 at 1:00 p.m. (FSN-TV). The task ahead for Twitter: N. 23 ^vs. #8 Kentucky (13) L 74-67 the Huskies is daunting. UW has previously swept the L.A. schools http://twitter.com/UWSportsNews N. 24 ^vs. #2 Michigan State (13) L 76-71 only twice -- 2006 and 1987. The last time UW swept a two-game N. 30 Long Beach State (23) W 102-75 Pac-10 road series to start a season was in 1976 when they won Upcoming Games D. -

Rosters Set for 2014-15 Nba Regular Season

ROSTERS SET FOR 2014-15 NBA REGULAR SEASON NEW YORK, Oct. 27, 2014 – Following are the opening day rosters for Kia NBA Tip-Off ‘14. The season begins Tuesday with three games: ATLANTA BOSTON BROOKLYN CHARLOTTE CHICAGO Pero Antic Brandon Bass Alan Anderson Bismack Biyombo Cameron Bairstow Kent Bazemore Avery Bradley Bojan Bogdanovic PJ Hairston Aaron Brooks DeMarre Carroll Jeff Green Kevin Garnett Gerald Henderson Mike Dunleavy Al Horford Kelly Olynyk Jorge Gutierrez Al Jefferson Pau Gasol John Jenkins Phil Pressey Jarrett Jack Michael Kidd-Gilchrist Taj Gibson Shelvin Mack Rajon Rondo Joe Johnson Jason Maxiell Kirk Hinrich Paul Millsap Marcus Smart Jerome Jordan Gary Neal Doug McDermott Mike Muscala Jared Sullinger Sergey Karasev Jannero Pargo Nikola Mirotic Adreian Payne Marcus Thornton Andrei Kirilenko Brian Roberts Nazr Mohammed Dennis Schroder Evan Turner Brook Lopez Lance Stephenson E'Twaun Moore Mike Scott Gerald Wallace Mason Plumlee Kemba Walker Joakim Noah Thabo Sefolosha James Young Mirza Teletovic Marvin Williams Derrick Rose Jeff Teague Tyler Zeller Deron Williams Cody Zeller Tony Snell INACTIVE LIST Elton Brand Vitor Faverani Markel Brown Jeffery Taylor Jimmy Butler Kyle Korver Dwight Powell Cory Jefferson Noah Vonleh CLEVELAND DALLAS DENVER DETROIT GOLDEN STATE Matthew Dellavedova Al-Farouq Aminu Arron Afflalo Joel Anthony Leandro Barbosa Joe Harris Tyson Chandler Darrell Arthur D.J. Augustin Harrison Barnes Brendan Haywood Jae Crowder Wilson Chandler Caron Butler Andrew Bogut Kentavious Caldwell- Kyrie Irving Monta Ellis