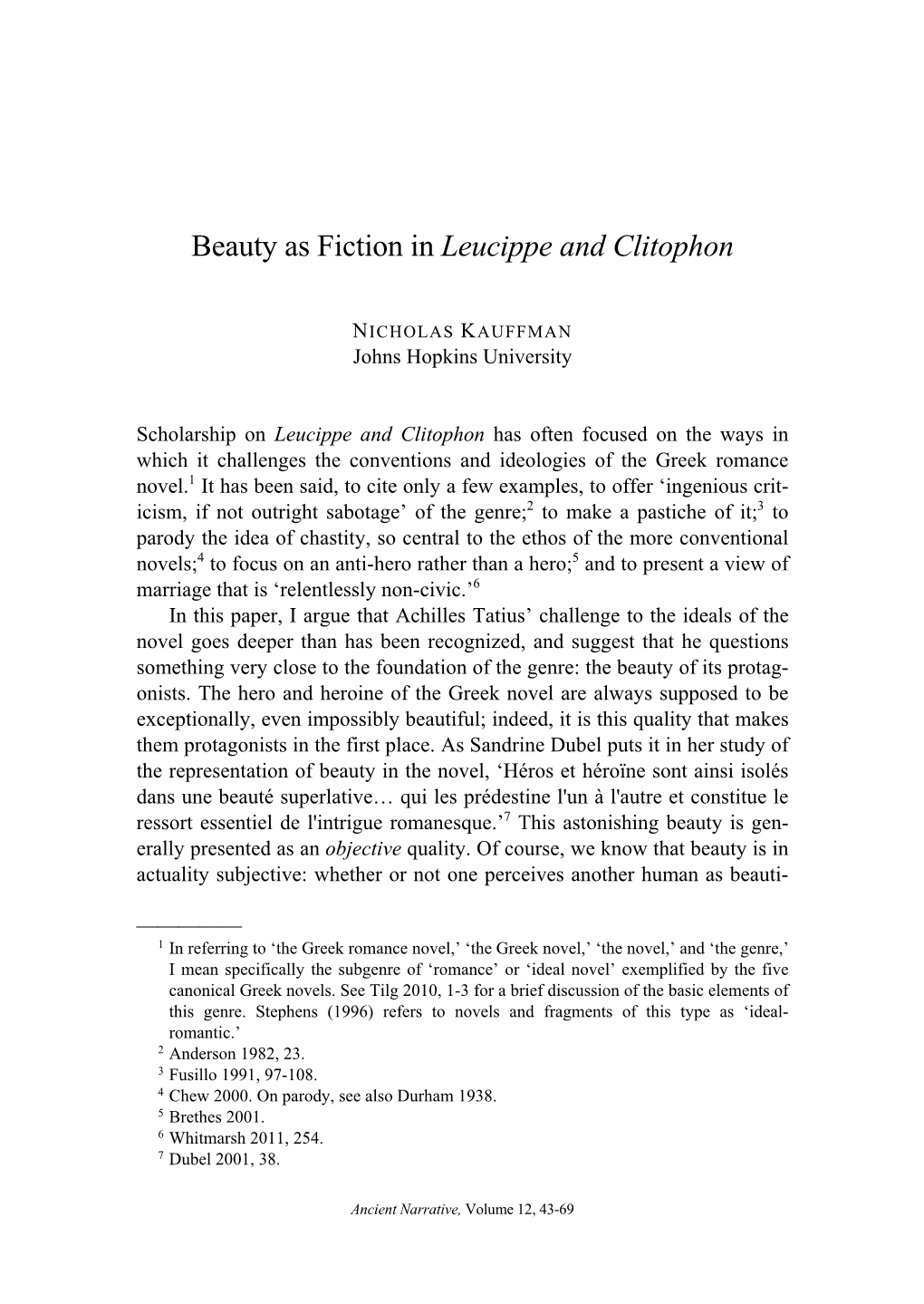

Beauty As Fiction in Leucippe and Clitophon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pleasure and Instruction in the Prologue of Longus

SYMBOLAE PHILOLOGORUM POSNANIENSIUM GRAECAE ET LATINAE XIX• 2009 pp. 95-114. ISBN 978-83-232-2153-1. ISSN 0302-7384 ADAM MICKIEWICZUNIVERSITYPRESS, POZNAŃ BRUCE DUNCAN MACQUEEN Department of Comparative Literature, University of Silesia pl. Sejmu Śląskiego 1, 40-032 Katowice Poland PLEASURE AND INSTRUCTION IN THE PROLOGUE OF LONGUS’ DAPHNIS AND CHLOE ABSTRACT . Bruce Duncan MacQueen, Pleasure and instruction in the Prologue of Longus’ “Daphnis and Chloe”. The present study attempts to demonstrate that the ancient Greek novel Daphnis and Chloe system- atically explores the problem expressed by Horace in the phrase docere et delectare, and that this purpose is announced in the Prologue. The functions of prologues as such are briefly reviewed. After a consideration of the prologues of the remaining ancient Greek novels, the Prologue of Longus’s Daphnis and Chloe is analyzed line by line. Longus uses the Prologue, then, to establish a series of dialectical tensions that operate throughout the novel, allowing it to delight and instruct at the same time. Key words: ancient Greek novel, Eros, paradox, paideia, hunting. INTRODUCTION A paradox often repeated, like a metaphor, eventually loses the shock value that makes it useful as a figure of speech. To use the terminology of cognitive psychology, it comes to be “overlearned,” repeated without reflec- tion at particular moments when the requisite prompt occurs. Its very fa- miliarity makes it fade into the background, where it ceases to draw atten- tion to itself. We have been told since childhood, for example, to “turn the other cheek,” so we repeat the phrase automatically and almost entirely ignore it in practice, since it no longer demands our attention. -

Reviving the Pagan Greek Novel in a Christian World Burton, Joan B Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1998; 39, 2; Proquest Pg

Reviving the Pagan Greek novel in a Christian World Burton, Joan B Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1998; 39, 2; ProQuest pg. 179 Reviving the Pagan Greek Novel in a Christian World Joan B. Burton N THE CHRISTIAN WORLD of Constantinople, in the twelfth century A.D., there was a revival of the ancient Greek novel, I replete with pagan gods and pagan themes. The aim of this paper is to draw attention to the crucial role of Christian themes such as the eucharist and the resurrection in the shaping and recreation of the ancient pagan Greek world in the Byzan tine Greek novels. Traditionally scholars have focused on similarities to the ancient Greek novels in basic plot elements, narrative tech niques, and the like. This has often resulted in a general dismissal of the twelfth-century Greek novels as imitative and unoriginal.1 Yet a revision of this judgment has begun to take place.2 Scholars have noted that there are themes and imagery in these novels that would sound contemporary to many of their Byzantine readers, for example, ceremonial throne scenes and 1 Thus B. E. Perry, The Ancient Romances: A Literary-Historical Account of Their Origins (Berkeley 1967) 103: "the slavish imitations of Achilles Tatius and Heliodorus which were written in the twelfth century by such miserable pedants as Eustathius Macrembolites, Theodorus Prodromus, and Nicetas Eugenianus, trying to write romance in what they thought was the ancient manner. Of these no account need be taken." 2See R. Beaton's important book, The Medieval Greek Romance 2 (London 1996) 52-88, 210-214; M. -

Silencing the Female Voice in Longus and Achilles Tatius

Silencing the female voice in Longus and Achilles Tatius Word Count: 12,904 Exam Number: B052116 Classical Studies MA (Hons) School of History, Classics and Archaeology University of Edinburgh B052116 Acknowledgments I am indebted to the brilliant Dr Calum Maciver, whose passion for these novels is continually inspiring. Thank you for your incredible supervision and patience. I’d also like to thank Dr Donncha O’Rourke for his advice and boundless encouragement. My warmest thanks to Sekheena and Emily for their assistance in proofreading this paper. To my fantastic circle of Classics girls, thank you for your companionship and humour. Thanks to my parents for their love and support. To Ben, for giving me strength and light. And finally, to the Edinburgh University Classics Department, for a truly rewarding four years. 1 B052116 Table of Contents Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………………….1 List of Abbreviations………………………………………………………………………3 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………….4 Chapter 1: Through the Male Lens………………………………………………………6 The Aftertaste of Sophrosune……………………………………………………………….6 Male Viewers and Voyeuristic Fantasy.…………………………………………………....8 Narratorial Manipulation of Perspective………………………………………………….11 Chapter 2: The Mythic Hush…………………………………………………………….15 Echoing Violence in Longus……………………………………………………………….16 Making a myth out of Chloe………………………………………………………………..19 Leucippe and Europa: introducing the mythic parallel……………………………………21 Andromeda, Philomela and Procne: shifting perspectives………………………………...22 Chapter 3: Rupturing the -

Calasiris the Pseudo-Greek Hero: Odyssean Allusions in Heliodorus' Aethiopica

Calasiris the Pseudo-Greek Hero: Odyssean Allusions in Heliodorus' Aethiopica Christina Marie Bartley A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master’s degree in Classical Studies Department of Classics and Religious Studies Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Christina Marie Bartley, Ottawa, Canada, 2021 Table of Contents Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................... iii Abstract .............................................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... vii Introduction ..................................................................................................................... viii 1. The Structural Markers of the Aethiopica .......................................................................1 1.1.Homeric Strategies of Narration ..........................................................................................2 1.1.1. In Medias Res .................................................................................................................3 1.2. Narrative Voices .................................................................................................................8 1.2.1. The Anonymous Primary Narrator ................................................................................9 1.2.2. Calasiris........................................................................................................................10 -

Theagenes' Sōphrosynē in Heliodorus' Aethiopica

Virtue Obscured: Theagenes’ Sōphrosynē in Heliodorus’ Aethiopica RACHEL BIRD Swansea University The concept of sōphrosynē has a central role in the genre of the Greek novel.1 The five extant texts have at their heart the representation of a mutual, heterosexual erotic relationship between beautiful, aristocratic youths and, in all of the novels apart from Longus’ Daphnis and Chloe, the protagonists’ possession of sōphrosynē is a crucial part of their identity. They must prove their sōphrosynē when faced with sexual advances from lustful antagonists, and they often prove their fidelity through their innate regard for this virtue. While as a term and con- cept sōphrosynē2 is semantically complex, encompassing the qualities and psy- chological states of temperance, moderation, sanity, self-control and chastity, in the novels it generally refers to sexual restraint and the motivation behind chastity. The texts differ in their respective treatments of sōphrosynē: there is a spectrum from the representation of mutual chastity in Xenophon of Ephesus’ novel, which has been labelled obsessive,3 to the irreverent subversion of chastity found in Achilles Tatius’ Leucippe and Clitophon.4 Despite these divergent treatments, the role of sōphrosynē is always fundamental to the ethics of these novels. Heliodorus’ Aethiopica has long been considered a complex work, particu- larly in terms of its narrative structure.5 The characterisation of its protagonists ————— 1 I consider the five extant works of Chariton, Xenophon of Ephesus, Longus, Achilles Ta- tius and Heliodorus to be examples of the genre of the Greek novel. For discussion of sōphrosynē in the novels, see Anderson 1997; De Temmerman 2014; Kaspryzsk 2009. -

Seeing Gods: Epiphany and Narrative in the Greek Novels

Seeing Gods: Epiphany and Narrative in the Greek Novels ROBERT L. CIOFFI Bard College The Greek world was full of the divine, and the imagined world of the ancient novels was no different.1 Divinity and its worship pervade the novels’ narra- tives, helping to unite, drive apart, and then reunite their protagonists. In this paper, I explore the relationship between ancient religion and literature, the transformation of literary tradition, and the place of the marvelous in the nov- els’ narratives by examining the role that one aspect of the human experience of the gods, epiphany, plays in the genre. Although the novelists describe very few scenes of actual epiphany,2 they make abundant use of the epiphanic met- aphor in what I will call “epiphanic situations,” when an internal audience reacts to the hero or, most often, the heroine of the novel as if he or she were a god or goddess. These epiphanic situations transform the common metaphor of divine beauty into a reality, at least as experienced by the internal audience,3 and they offer the novelists an alternative to ekphrasis for expressing ineffable beauty. ————— 1 Zeitlin 2008, 91 writes: “The novels are full of: temples, shrines, altars, priests, rituals and offerings, dreams (or oracles), prophecies, divine epiphanies, aretalogies, mystic language and other metaphors of the sacred (not forgetting, in addition, exotic barbarian rites).” 2 In the novels, mortals are most frequently visited by divinities during dreams: e.g., Chari- ton 2,3; X. Eph. 1,12; Longus 1,7-8, 2,23, 2,26-27, 3,27, 4,34; Ach. -

The Spell of Achilles Tatius: Magic and Metafiction in Leucippe and Clitophon

The Spell of Achilles Tatius: Magic and Metafiction in Leucippe and Clitophon ASHLI J.E. BAKER Bucknell University Eros is “…δεινὸς γόης καὶ φαρμακεὺς καὶ σοφιστής…” (Plato, Symposium 203d) Introduction In the beginning of Book Two of Achilles Tatius’ Leucippe and Clitophon, the clever but thus far failed lover Clitophon witnesses a remarkable – and useful – scene. He passes by just as Clio, Leucippe’s slave, is stung on the hand by a bee. He sees Leucippe soothe Clio’s pain by singing incantations (ἐπᾴδω) she says she learned from an Egyptian woman.1 When Clitophon, determined to woo Leu- cippe, finds himself alone with her on the following day, he pretends that he too has been stung by a bee. Leucippe approaches, asking where he has been stung. In reply, Clitophon says, ————— 1 παύσειν γὰρ αὐτὴν τῆς ἀλγηδόνος δύο ἐπᾴσασαν ῥήματα· διδαχθῆναι γὰρ αὐτὴν ὑπό τινος Αἰγυπτίας εἰς πληγὰς σφηκῶν καὶ μελιττῶν. Καὶ ἅμα ἐπῇδε· καὶ ἔλεγεν ἡ Κλειὼ μετὰ μικρὸν ῥᾴων γεγονέναι. (2.7 - “…she would, she said, stop her pain by chanting two spells; she had been taught by an Egyptian woman how to deal with wasp- and bee-stings. As she had chanted, Clio had said that the pain was gradually relieved.”). All Greek text of Leu- cippe and Clitophon is that of Garnaud 1991. All translations are cited, with occasional alterations, from Whitmarsh 2001. I want to give special thanks to Catherine Connors for her insightful comments throughout the drafting of this paper. Thanks too to Alex Hollmann and Stephen Trzaskoma for feedback on earlier versions of this project. -

Publications 2020

Faculty of Classics, University of Oxford: publications 2020 This list contains some of the work published by members of the Faculty with the year of publication 2020. Allan, W. (2020), ‘Poetry and Philosophy in the Sophists’, Araucaria 44: 285-302. Armstrong, R. (2020), ‘Hercules and the Stone Tree: Aeneid 8.233–40’ CQ 70.2. Ashdowne, R. (2020), ‘-mannus makyth man(n)? Latin as an indirect source for English lexical history’ in L. Wright (ed.), The Multilingual Origins of Standard English (Berlin & Boston), 411-441. Ballesteros. B. (2020), 'Poseidon and Zeus in Iliad 7 and Odyssey 13: on a case of Homeric imitation’, Hermes: Zeitschrift für Klassische Philologie 148: 259–277. Benaissa, A. (2020), ‘A Papyrus of Hermogenes’ On Issues in the Bodleian Library’, Archiv für Papyrusforschung 66.2: 265–272. Benaissa, A. (2020), ‘The Will of Haynchis Daughter of Isas’, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 214: 230–235. Benaissa, A. (2020), ‘Late Antique Papyri from Hermopolis in the British Library I’, Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 215: 257–272. Benaissa, A. (2020), ‘P.Oxy. LXXVII 5123 and the Economic Relations between the Apion Estate and its Coloni Adscripticii’, Journal of Juristic Papyrology 50 (forthcoming 2020). Beniassa, A. (2020), ‘An Official Deposition from the Early Fifth Century’, in J. V. Stolk and G. van Loon (eds.), Text Editions of (Abnormal) Hieratic, Demotic, Greek, Latin and Coptic Papyri and Ostraca. ‘Some People Love Their Friends Also When They Are Far Away’: Festschrift in Honour of Franscisca A.J. Hoogendijk (Leiden), 167–170. Benaissa, A. (2020),‘Notes on Oxyrhynchite Toponyms’, Tyche 35 (forthcoming 2020). -

1 INTRODUCTION Achilles Tatius Despite the Explosion of Interest In

Cambridge University Press 0521642647 - Vision and Narrative in Achilles Tatius’ Leucippe and Clitophon Helen Morales Excerpt More information 1 INTRODUCTION Achilles Tatius Despite the explosion of interest in ancient fiction over the last few decades, Leucippe and Clitophon remains the least studied of the five major Greek novels. To my knowledge, this is the first published monograph on Achilles; so far Leucippe has been left on the shelf. ‘Most moderns,’ explains Ewen Bowie in his entry on Achilles Tatius in the Oxford Classical Dictionary, ‘uncertain how to evaluate him, prefer Longus and Heliodorus.’1 Graham Anderson concurs: ‘Even at the lowest level of literary criticism, at which writers receive one-word adjectives, one can do something for the rest of the extant novelists: Xenophon of Ephesus is na¨ıve, Heliodorus cleverly convoluted, Longus artfully simple: yet what is one to say about Achilles?’2 Scholarship on the novel is moving forward so quickly that these comments will soon seem dated. Nevertheless, they are symptomatic of a fundamental difficulty: there is no consensus about what to make of Achilles Tatius; at the most basic level, about how to read him. Parody? Pastiche? Pornography? It is, as John Morgan puts it, a ‘hyper-enigmatic’ novel.3 Part of the problem is that Achilles Tatius is frequently eval- uated against the norms of the genre (often as the Joker in the pack: ‘[Achilles Tatius] inverse syst´ematiquementles conventions du genre’;4 ‘He conducts a prolonged guerrilla war against the conventions of his own genre’5), and the norms and the genre are themselves problematic to define.6 It is important to note that recent approaches to the genre have been driven by the last few decades’ 1 OCD, 3rd edn (1996), 7. -

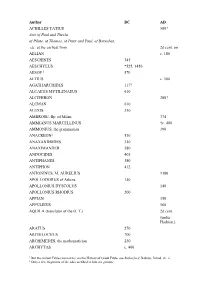

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

Euanthes and the World of Rhetoric in Achilles Tatius' Leucippe And

Euanthes and the World of Rhetoric in Achilles Tatius’ Leucippe and Cleitophon KATHERINE A. MCHUGH The University of Edinburgh In Book Three of Achilles Tatius’ Leucippe and Cleitophon there is an ekphrasis of a painting, one of three within the entirety of the novel. The description takes place after the protagonists’ arrival at Pelusium, as they happen upon the Temple of Zeus and come across “double images” (εἰκόνα διπλῆν, 3,6,3) which have been signed by the artist Euanthes (3,6,3).1 The main aim of this article is to consider the name of this artist, as opposed to the painting itself; it seeks to prove that Euanthes was not a real figure, but a name created by Achilles which is imbued with rhetorical references in keeping with the intellectual climate of 2nd Century AD Greek literature. The name Euanthes and its possible rhetorical connotations will be explored in conjunction with a detailed consideration of Achilles’ use of ekphrasis throughout Leucippe and Cleitophon and his interest in rhetorical edu- cation in order to assert that some of the author’s playful in-jokes have been un- derstudied, and that they can provide us with a clearer picture of how the author strives to appeal to his reader; that is, a reader who is steeped in a rhetorical edu- cation himself. The article also considers the other two ekphraseis of paintings in Leucippe and Cleitophon (which occur in Books One and Five) in order to aid with an understanding of Achilles’ use of the rhetorical technique and how sig- nificant rhetoric is to his novel as a whole. -

Thucydides, Sicily, and the Defeat of Athens Tim Rood

Thucydides, Sicily, and the Defeat of Athens Tim Rood To cite this version: Tim Rood. Thucydides, Sicily, and the Defeat of Athens. KTÈMA Civilisations de l’Orient, de la Grèce et de Rome antiques, Université de Strasbourg, 2017, 42, pp.19-39. halshs-01670082 HAL Id: halshs-01670082 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01670082 Submitted on 21 Dec 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Les interprétations de la défaite de 404 Edith Foster Interpretations of Athen’s defeat in the Peloponnesian war ............................................................. 7 Edmond LÉVY Thucydide, le premier interprète d’une défaite anormale ................................................................. 9 Tim Rood Thucydides, Sicily, and the Defeat of Athens ...................................................................................... 19 Cinzia Bearzot La συμφορά de la cité La défaite d’Athènes (405-404 av. J.-C.) chez les orateurs attiques .................................................. 41 Michel Humm Rome, une « cité grecque