The Pentlatch People of Denman Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gulf Islands Secondary Duncan Said the District's Desperate Three Ministry of Education Rep Island Distance Education School

L* . INSIDE! DWednesday, Jun^MmLe 18, 199 7 Vol. 39, No. 25 You* rA Communit y NewspapeMr , Salt Spring IslandIsland, B.Cs Rea. $1l (inclEstat. GSTe ) Local police seize real-looking gun from studenWmMfOCMt Ganges RCMP are consider Because the gun was hidden ing laying charges against a 15- in the youth's shirt, Seymour year-old youth who carried a said, it can be classified as a .177-calibre air gun onto school concealed weapon. The gun, grounds last week. which was seized along with a Held side by side with a real clip and pellet, does not shoot weapon, the seized gun is close bullets but is still considered a enough in appearance to fool firearm. most police officers, not to If shot, "it could take an eye mention ordinary citizens, said out," Seymour said. "If it hit in RCMP Const. Paul Seymour on the right place in the temple, it Monday. could kill someone." "It is a recipe for disaster," SIMS principal Bob added Seymour, who, even as a Brownsword said the school has firearms specialist, could not a "zero tolerance" for any type recognize the pellet gun as a of weapon. Last year, a switch fake at night or from a distance. blade comb was taken from a "If we checked the kid and he student. "Even squirt guns are pulled it out, we would normal prohibited," he said. ly assume it was a firearm and Seymour said the youth could respond accordingly with possi be charged with possession of a ble catastrophic results," he concealed weapon or possession said. -

Francophone Historical Context Framework PDF

Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Canot du nord on the Fraser River. (www.dchp.ca); Fort Victoria c.1860. (City of Victoria); Fort St. James National Historic Site. (pc.gc.ca); Troupe de danse traditionnelle Les Cornouillers. (www. ffcb.ca) September 2019 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Table of Contents Historical Context Thematic Framework . 3 Theme 1: Early Francophone Presence in British Columbia 7 Theme 2: Francophone Communities in B.C. 14 Theme 3: Contributing to B.C.’s Economy . 21 Theme 4: Francophones and Governance in B.C. 29 Theme 5: Francophone History, Language and Community 36 Theme 6: Embracing Francophone Culture . 43 In Closing . 49 Sources . 50 2 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework - cb.com) - Simon Fraser et ses Voya ses et Fraser Simon (tourisme geurs. Historical contexts: Francophone Historic Places • Identify and explain the major themes, factors and processes Historical Context Thematic Framework that have influenced the history of an area, community or Introduction culture British Columbia is home to the fourth largest Francophone community • Provide a framework to in Canada, with approximately 70,000 Francophones with French as investigate and identify historic their first language. This includes places of origin such as France, places Québec, many African countries, Belgium, Switzerland, and many others, along with 300,000 Francophiles for whom French is not their 1 first language. The Francophone community of B.C. is culturally diverse and is more or less evenly spread across the province. Both Francophone and French immersion school programs are extremely popular, yet another indicator of the vitality of the language and culture on the Canadian 2 West Coast. -

Escribe Agenda Package

Hornby Island Local Trust Committee Regular Meeting Revised Agenda Date: June 8, 2018 Time: 11:30 am Location: Room to Grow 2100 Sollans Road, Hornby Island, BC Pages 1. CALL TO ORDER 11:30 AM - 11:30 AM "Please note, the order of agenda items may be modified during the meeting. Times are provided for convenience only and are subject to change.” 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 3. TOWN HALL AND QUESTIONS 11:35 AM - 11:45 AM 4. COMMUNITY INFORMATION MEETING - none 5. PUBLIC HEARING - none 6. MINUTES 11:45 AM - 11:50 AM 6.1 Local Trust Committee Minutes dated April 27, 2018 for Adoption 4 - 14 6.2 Section 26 Resolutions-without-meeting - none 6.3 Advisory Planning Commission Minutes - none 7. BUSINESS ARISING FROM MINUTES 11:50 AM - 12:15 PM 7.1 Follow-up Action List dated May 31 , 2018 15 - 16 7.2 First Nations and Housing Issues - Memorandum 17 - 18 8. DELEGATIONS 12:15 PM - 12:25 PM 8.1 Presentation by Ellen Leslie and Dr. John Cox regarding Hornby Water Stewardship - A Project of Heron Rocks Friendship Centre Society - to be Distributed 9. CORRESPONDENCE Correspondence received concerning current applications or projects is posted to the LTC webpage ---BREAK---- 12:25 PM TO 12:40 PM 10. APPLICATIONS AND REFERRALS 12:40 PM - 1:00 PM 10.1 HO-ALR-2018.1 (Colin) - Staff Report 19 - 39 10.1.1 Agriculture on Hornby Island - Background Information from Trustee Law 40 - 41 10.2 Denman Island Bylaw Referral Request for Review and Response regarding Bylaw 42 - 44 Nos. -

Deep-Water Stratigraphic Evolution of the Nanaimo Group, Hornby and Denman Islands, British Columbia

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2016 Deep-Water Stratigraphic Evolution of The Nanaimo Group, Hornby and Denman Islands, British Columbia Bain, Heather Bain, H. (2016). Deep-Water Stratigraphic Evolution of The Nanaimo Group, Hornby and Denman Islands, British Columbia (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/25535 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/3342 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Deep-Water Stratigraphic Evolution of The Nanaimo Group, Hornby and Denman Islands, British Columbia by Heather Alexandra Bain A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2016 © Heather Alexandra Bain 2016 ABSTRACT Deep-water slope strata of the Late Cretaceous Nanaimo Group at Hornby and Denman islands, British Columbia, Canada record evidence for a breadth of submarine channel processes. Detailed observations at the scale of facies and stratigraphic architecture provide criteria for recognition and interpretation of long-lived slope channel systems, emphasizing a disparate relationship between stratigraphic and geomorphic surfaces. The composite submarine channel system deposit documented is 19.5 km wide and 1500 m thick, which formed and filled over ~15 Ma. -

Back-To-The-Land on the Gulf Islands and Cape Breton

Making Place on the Canadian Periphery: Back-to-the-Land on the Gulf Islands and Cape Breton by Sharon Ann Weaver A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Sharon Ann Weaver, July 2013 ABSTRACT MAKING PLACE ON THE CANADIAN PERIPHERY: BACK-TO- THE-LAND ON THE GULF ISLANDS AND CAPE BRETON Sharon Ann Weaver Advisor: University of Guelph, 2013 Professor D. McCalla This thesis investigates the motivations, strategies and experiences of a movement that saw thousands of young and youngish people permanently relocate to the Canadian countryside during the 1970s. It focuses on two contrasting coasts, Denman, Hornby and Lasqueti Islands in the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia, and three small communities near Baddeck, Cape Breton. This is a work of oral history, based on interviews with over ninety people, all of whom had lived in their communities for more than thirty years. It asks what induced so many young people to abandon their expected life course and take on a completely new rural way of life at a time when large numbers were leaving the countryside in search of work in the cities. It then explores how location and the communities already established there affected the initial process of settlement. Although almost all back-to-the-landers were critical of the modern urban and industrial project; they discovered that they could not escape modern capitalist society. However, they were determined to control their relationship to the modern economic system with strategies for building with found materials, adopting older ways and technologies for their homes and working off-property as little as possible. -

Black Diamond City Jan Peterson Recorded As Presented to The

Black Diamond City Jan Peterson Recorded as presented to the Nanaimo Historical Society on October 10, 2002 Transcribed by Dalys Barney, Vancouver Island University Library on June 12, 2020 Pamela Mar Nanaimo Historical Society. Thursday, October 10, 2002, at the society's regular meeting. Introducing author Jan Peterson, who has written a book on the first 50 years of Nanaimo which will be published shortly. [recording stops and restarts] Daphne Paterson Can you hear me? Anyway, to introduce one of our own, the author of the most recent book on Nanaimo, Jan Peterson. Jan is an import from Scotland to Ontario in 1957, and she moved to the Alberni Valley with Ray and their children in 1972. There she worked as a reporter for the Alberni Valley Times and is the author of four books on the history of Port Alberni and the area. One of them, you may remember, is on Cathedral Grove. Two of her books received awards from the B.C. Historical Federation. The Petersons retired here in Nanaimo six years ago. And after four years of meticulous research, her first work on Nanaimo will be launched…next month? Jan Peterson This month. Daphne Paterson This month! Jan Peterson November 20th. Daphne Paterson November 20th. As a note for all of us here, to me it's significant that Jan has made extensive use of the records now held by the Nanaimo Community Archives. And, to me, it upholds our belief in the value of the archival material in this community as being very well grounded. For those of you who are new here, it was the Nanaimo Historical Society who initiated the Nanaimo Community Archives. -

History 351: Twentieth Century British Columbia Section S16 N01 – Building 250 Room 140 Tuesdays and Thursdays from 2:30 to 4:00 Pm

Vancouver Island University – Nanaimo Campus Territory of the Coast Salish Snuneymuxw First Nation Department of History History 351: Twentieth Century British Columbia Section S16 N01 – Building 250 Room 140 Tuesdays and Thursdays from 2:30 to 4:00 pm. Instructor: Kelly Black Email: [email protected] Office: Building 340 / Office 123 Phone: (250) 753-3245, x 2132 Office Hours: Tuesdays & Thursdays, 1:00pm to 2:00pm. Course Objectives • To introduce students to key events and themes in the history of British Columbia. • To foster analytical thinking, research and communication skills. • To introduce students to the concept of public history. • To demonstrate the practical and everyday importance of history. • To engage students with local history and the communities in which we live and learn. Course Themes • Colonialism • Resource Extraction • Political Conflict • Environmentalism / Conservation • Provincial Identity Readings There is no textbook for this course. There are however mandatory weekly readings. These readings are posted on VIU Learn (D2L). These assigned readings (see below and VIU Learn) should be completed before each class and will inform each lecture and in- class discussion. While there is no textbook for this class, I suggest budgeting approximately $15 for the potential cost of materials associated with the public history assignment. Updated January 10, 2015 1 Course Schedule Week 1 January 5: Introduction - N/A January 7: “The Queen is Dead!” - Introduction to Sources: http://web.uvic.ca/vv/student/victoria_dead/index.html -

Volume 93, Number 27 4,572Nd Meeting Friday, February 1, 2013

Volume 93, Number 27 4,572nd Meeting Friday, February 1, 2013 PP Dave Hammond, Egon Holzworth, Jan Petersen, President Joan holding the Haggis, Piper Neil Westmacott, Douglas Anderson and PADG Brenda Grice prepare to pipe in the Haggis. Club Meeting Friday at 12:00 p.m. Serving Our Community Since at the Coast Bastion Inn May 1, 1920 - Charter Number 43 CLUB OFFICERS 2012-2013 DIRECTORS Doug Cowling Brent Stetar Susie Walker President ....................................................... Joan Ryan John Shillabeer Chris Pogson Susan Gerrand Vice President ............................................... Wahid Ali Secretary ........................................................ Bob Janes President Rotary International Treasurer .............................................. Gordon Hubley Sakuji Tanaka, Rotary Club of Yashio, Japan President Elect ................................. Douglas Anderson District Governor Assistant Governor Immediate Past President ..................... Dave Hammond Judy Byron, Sidney, BC Barry Sparkes, Lantzville, BC Mailing Address: P.O. Box 405, Nanaimo, B.C. V9R 5L3 — web: www.rotarynanaimo.org Meeting Notes for 25 January here. Jerry introduced Eric Brand Happy and Sad Bucks 2013 a prospective member and Lila was happy as she will By John Shillabeer Brenda Grice introduced Lorreta shortly collect her aunt and bring Petersen who is from Nanaimo and This being Robbie Burns Day her to Nanaimo (by air), even we hope is also a prospective mem- though Auntie doesn’t want to pay. (aka Haggis Day) Basil Hobbs be- ber. Basil Hobbs introduced and gan the ceremonies as MC. thanked Neil Westmacott for pip- Susie Walker was happy she Charles Ramos gave the invoca- ing in the haggis has some Scottish ancestry. tion and then Neil Westmacott Health of the Club Dave Connolly was happy be- piped “ A man’s a man for a’ that “ cause he felt the club singing O Bob Fenty told us that Wayne Canada was the best he had heard Anderson had been admitted to in a very long time. -

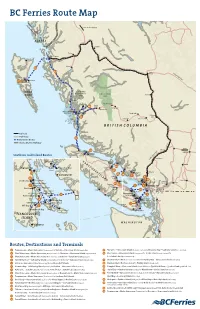

BC Ferries Route Map

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver -

From Settlement to Return

Lifting the Veil on Nanaimo’s Nikkei Community: From Settlement to Return Masako Fukawa* s a Sansei (third-generation Japanese Canadian) who has lived in Nanaimo for thirty years and whose family engaged in the fishing industry, I was curious about the history of the Nikkei A(members of the Japanese diaspora) in Nanaimo. Coincidentally, in 2016, a Nanaimo Community Archives report concluded that, with census data as “virtually” the only archival source, the community “remained largely veiled.”1 Thus, this article is an attempt to lift the veil and to reveal the history of Nanaimo’s Nikkei community, from early settlement to its growth and pivotal role in the fishery, to its forced removal in 1942 and, finally, to its rebirth many years later.2 Building on previous discussions of the Japanese Canadian presence in the city, I consulted interviews with present and former Japanese and non-Japanese residents, several of whom are now deceased, as well as census data, newspapers, government documents, and other sources to recapture the story of a once vibrant community. 3 This history also reveals an ugly side of Nanaimo: like other com- munities in British Columbia, its residents called for the expulsion of Japanese Canadians. Because few Japanese Canadians returned to * My appreciation to John Price for his leadership as director of the ACVI project and for his encouragement and insightful comments on this article. Thanks also to Christine O’Bonsawin and the two anonymous reviewers for providing me with valuable comments, one of whom provided substantial copyediting assistance. 1 Nanaimo Community Archives, The Japanese in Nanaimo: Preliminary Report on Sources and Findings, compiled by Nanaimo Archives, 2016. -

I His Clock Is on the Tower STUDY GROUP WANTS YOUR HELP

nftluoob Serving fhe islands that make Beautiful British Columbia Beautiful Sixteenth Year, No. 27 GANGES, British Columbia Wednesday, July 16, 1975 $5.00 per year in Canada, 15$ copy i His clock is on the tower ON SALT SPRING ISLAND Watershed lots are 10 acres — FOLLOWING BALLOTING Minimum lot size in desig- Change on the by-law con- nated watershed area on Salt forms to the change approved Spring Island has been chang- in the official community plar ed. In the new Salt Spring Is- and the 10-acre minimum is land Subdivision by-law, the now binding on island property size indicated is a minimum owners. of 10 acres. Final draft of the subdivision The change from the earli- by-law ha? not yet been pre- er limit of five acres has been pared. Islanders and profes- brought about by the Salt sional planners are engaged Spring Island branch of the in a series of meetings to iron Society of Pollution and En- vironmental Control. SPEC it out. made the proposal last year. The society asked the Capital Regional Board to make the change and the Board passed POLICE the plea on to the Salt Spring Island Community Planning Association. OFFICE The association co-operat- ed with the board in present- ing a series of ballots in Drift- wood, inviting island voters GROWING What time is it? Look at your fire hall.,.others do and set their clocks by it. to express an opinion. Response showed some ?l°/o Change has been made in the RCMP office on Salt Sprinj • He's a man with a way with one of a number of brothers furniture for children and theii¥ in favour of making the elders. -

Salish Sea Nearshore Conservation Project 2013-2015

2013-2015 Final Report Salish Sea Nearshore Conservation Project Prepared for: Pacific Salmon Foundation Recreational Fisheries Conservation Partnerships Program Environment Canada (EcoAction) Nikki Wright, Executive Director SeaChange Marine Conservation Society [email protected] 1 March 2015 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................................................. 3 1 Eelgrass Inventories .................................................................................. 4 2 Mapping Methodology ............................................................................. 4 2.1 Linear Mapping ........................................................................................ 5 2.2 Polygon Mapping ..................................................................................... 5 2.3 Distribution .............................................................................................. 6 2.4 Form ......................................................................................................... 6 2.5 Sediment Types ........................................................................................ 6 2.6 Percent of Cover ....................................................................................... 7 2.7 Tidal Fluctuations ..................................................................................... 7 2.8 Presence of Other Vegetation .................................................................. 7 2.9 Visibility ...................................................................................................