Dry Oak–Hickory Forest (Piedmont Subtype)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Nebraska Woody Plants

THE NEBRASKA STATEWIDE ARBORETUM PRESENTS NATIVE NEBRASKA WOODY PLANTS Trees (Genus/Species – Common Name) 62. Atriplex canescens - four-wing saltbrush 1. Acer glabrum - Rocky Mountain maple 63. Atriplex nuttallii - moundscale 2. Acer negundo - boxelder maple 64. Ceanothus americanus - New Jersey tea 3. Acer saccharinum - silver maple 65. Ceanothus herbaceous - inland ceanothus 4. Aesculus glabra - Ohio buckeye 66. Cephalanthus occidentalis - buttonbush 5. Asimina triloba - pawpaw 67. Cercocarpus montanus - mountain mahogany 6. Betula occidentalis - water birch 68. Chrysothamnus nauseosus - rabbitbrush 7. Betula papyrifera - paper birch 69. Chrysothamnus parryi - parry rabbitbrush 8. Carya cordiformis - bitternut hickory 70. Cornus amomum - silky (pale) dogwood 9. Carya ovata - shagbark hickory 71. Cornus drummondii - roughleaf dogwood 10. Celtis occidentalis - hackberry 72. Cornus racemosa - gray dogwood 11. Cercis canadensis - eastern redbud 73. Cornus sericea - red-stem (redosier) dogwood 12. Crataegus mollis - downy hawthorn 74. Corylus americana - American hazelnut 13. Crataegus succulenta - succulent hawthorn 75. Euonymus atropurpureus - eastern wahoo 14. Fraxinus americana - white ash 76. Juniperus communis - common juniper 15. Fraxinus pennsylvanica - green ash 77. Juniperus horizontalis - creeping juniper 16. Gleditsia triacanthos - honeylocust 78. Mahonia repens - creeping mahonia 17. Gymnocladus dioicus - Kentucky coffeetree 79. Physocarpus opulifolius - ninebark 18. Juglans nigra - black walnut 80. Prunus besseyi - western sandcherry 19. Juniperus scopulorum - Rocky Mountain juniper 81. Rhamnus lanceolata - lanceleaf buckthorn 20. Juniperus virginiana - eastern redcedar 82. Rhus aromatica - fragrant sumac 21. Malus ioensis - wild crabapple 83. Rhus copallina - flameleaf (shining) sumac 22. Morus rubra - red mulberry 84. Rhus glabra - smooth sumac 23. Ostrya virginiana - hophornbeam (ironwood) 85. Rhus trilobata - skunkbush sumac 24. Pinus flexilis - limber pine 86. Ribes americanum - wild black currant 25. -

The Natural Communities of South Carolina

THE NATURAL COMMUNITIES OF SOUTH CAROLINA BY JOHN B. NELSON SOUTH CAROLINA WILDLIFE & MARINE RESOURCES DEPARTMENT FEBRUARY 1986 INTRODUCTION The maintenance of an accurate inventory of a region's natural resources must involve a system for classifying its natural communities. These communities themselves represent identifiable units which, like individual plant and animal species of concern, contribute to the overall natural diversity characterizing a given region. This classification has developed from a need to define more accurately the range of natural habitats within South Carolina. From the standpoint of the South Carolina Nongame and Heritage Trust Program, the conceptual range of natural diversity in the state does indeed depend on knowledge of individual community types. Additionally, it is recognized that the various plant and animal species of concern (which make up a significant remainder of our state's natural diversity) are often restricted to single natural communities or to a number of separate, related ones. In some cases, the occurrence of a given natural community allows us to predict, with some confidence, the presence of specialized or endemic resident species. It follows that a reasonable and convenient method of handling the diversity of species within South Carolina is through the concept of these species as residents of a range of natural communities. Ideally, a nationwide classification system could be developed and then used by all the states. Since adjacent states usually share a number of community types, and yet may each harbor some that are unique, any classification scheme on a national scale would be forced to recognize the variation in a given community from state to state (or region to region) and at the same time to maintain unique communities as distinctive. -

Lyonia Preserve Plant Checklist

Lyonia Preserve Plant Checklist Volusia County, Florida Aceraceae (Maple) Asteraceae (Aster) Red Maple Acer rubrum Bitterweed Helenium amarum Blackroot Pterocaulon virgatum Agavaceae (Yucca) Blazing Star Liatris sp. Adam's Needle Yucca filamentosa Blazing Star Liatris tenuifolia Nolina Nolina brittoniana Camphorweed Heterotheca subaxillaris Spanish Bayonet Yucca aloifolia Cudweed Gnaphalium falcatum Dog Fennel Eupatorium capillifolium Amaranthaceae (Amaranth) Dwarf Horseweed Conyza candensis Cottonweed Froelichia floridana False Dandelion Pyrrhopappus carolinianus Fireweed Erechtites hieracifolia Anacardiaceae (Cashew) Garberia Garberia heterophylla Winged Sumac Rhus copallina Goldenaster Pityopsis graminifolia Goldenrod Solidago chapmanii Annonaceae (Custard Apple) Goldenrod Solidago fistulosa Flag Paw paw Asimina obovata Goldenrod Solidago spp. Mohr's Throughwort Eupatorium mohrii Apiaceae (Celery) Ragweed Ambrosia artemisiifolia Dollarweed Hydrocotyle sp. Saltbush Baccharis halimifolia Spanish Needles Bidens alba Apocynaceae (Dogbane) Wild Lettuce Lactuca graminifolia Periwinkle Catharathus roseus Brassicaceae (Mustard) Aquifoliaceae (Holly) Poorman's Pepper Lepidium virginicum Gallberry Ilex glabra Sand Holly Ilex ambigua Bromeliaceae (Airplant) Scrub Holly Ilex opaca var. arenicola Ball Moss Tillandsia recurvata Spanish Moss Tillandsia usneoides Arecaceae (Palm) Saw Palmetto Serenoa repens Cactaceae (Cactus) Scrub Palmetto Sabal etonia Prickly Pear Opuntia humifusa Asclepiadaceae (Milkweed) Caesalpinceae Butterfly Weed Asclepias -

Species List For: Engelmann Woods NA 174 Species

Species List for: Engelmann Woods NA 174 Species Franklin County Date Participants Location NA List NA Nomination List List made by Maupin and Kurz, 9/9/80, and 4/21/93 WGNSS Lists Webster Groves Nature Study Society Fieldtrip Participants WGNSS Vascular Plant List maintained by Steve Turner Species Name (Synonym) Common Name Family COFC COFW Acalypha virginica Virginia copperleaf Euphorbiaceae 2 3 Acer negundo var. undetermined box elder Sapindaceae 1 0 Acer saccharum var. undetermined sugar maple Sapindaceae 5 3 Achillea millefolium yarrow Asteraceae/Anthemideae 1 3 Actaea pachypoda white baneberry Ranunculaceae 8 5 Adiantum pedatum var. pedatum northern maidenhair fern Pteridaceae Fern/Ally 6 1 Agastache nepetoides yellow giant hyssop Lamiaceae 4 3 Ageratina altissima var. altissima (Eupatorium rugosum) white snakeroot Asteraceae/Eupatorieae 2 3 Agrimonia rostellata woodland agrimony Rosaceae 4 3 Ambrosia artemisiifolia common ragweed Asteraceae/Heliantheae 0 3 Ambrosia trifida giant ragweed Asteraceae/Heliantheae 0 -1 Amelanchier arborea var. arborea downy serviceberry Rosaceae 6 3 Antennaria parlinii var. undetermined (A. plantaginifolia) plainleaf pussytoes Asteraceae/Gnaphalieae 5 5 Aplectrum hyemale putty root Orchidaceae 8 1 Aquilegia canadensis columbine Ranunculaceae 6 1 Arisaema triphyllum ssp. triphyllum (A. atrorubens) Jack-in-the-pulpit Araceae 6 -2 Aristolochia serpentaria Virginia snakeroot Aristolochiaceae 6 5 Arnoglossum atriplicifolium (Cacalia atriplicifolia) pale Indian plantain Asteraceae/Senecioneae 4 5 Arnoglossum reniforme (Cacalia muhlenbergii) great Indian plantain Asteraceae/Senecioneae 8 5 Asarum canadense wild ginger Aristolochiaceae 6 5 Asclepias quadrifolia whorled milkweed Asclepiadaceae 6 5 Asimina triloba pawpaw Annonaceae 5 0 Asplenium rhizophyllum (Camptosorus) walking fern Aspleniaceae Fern/Ally 7 5 Asplenium trichomanes ssp. trichomanes maidenhair spleenwort Aspleniaceae Fern/Ally 9 5 Srank: SU Grank: G? * Barbarea vulgaris yellow rocket Brassicaceae 0 0 Blephilia hirsuta var. -

Black Oak Quercus Velutina Tree Acorns ILLINOIS RANGE

black oak Quercus velutina Kingdom: Plantae FEATURES Division: Magnoliphyta The deciduous black oak tree may grow to a height Class: Magnoliopsida of 80 feet and a diameter of about three and one- Order: Fagales half feet. The trunk is straight. The bark is black and deeply furrowed, with a yellow or orange inner bark. Family: Fagaceae The leaves are arranged alternately on the stem. The ILLINOIS STATUS simple leaf blade has seven to nine shallow lobes, each lobe bristle-tipped. The leaf is dark green, shiny common, native and smooth on the upper surface. It is hairy all over or hairy only along the veins on the lower surface. Each leaf may be 10 inches long and eight inches wide with a five-inch leafstalk. Male and female flowers are separate but located on the same tree. The tiny flower has no petals. Male (staminate) flowers are arranged in drooping clusters, while female (pistillate) flowers are in groups of one to four. The fruit is an acorn. Acorns may be single or in groups of two. The acorn is red-brown, ovoid or ellipsoid and not more than one-half enclosed by the cup. The cup appears to have a ragged edge. BEHAVIORS The black oak may be found statewide in Illinois. This tree grows in upland woods. It flowers in April tree and May when the leaves begin to unfold. The hard, red-brown wood is used in construction, for fuel and ILLINOIS RANGE for making fence posts.. acorns © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

The Following PLANTS Are Representative of the Many Species Found in the Woods

The following PLANTS are representative of the many species found in the Woods: Trees Muscadine (Vitis rotundifolia) Poison Ivy (Rhus radicans) Black Gum (Nyssa sylvatica) Wisteria* (Wisteria sinensis) Black Jack Oak (Q. marilandica) Yellow Jessamine (Gelsimium sempervirens) Blue Jack Oak (Q. incana) Dogwood (Cornus florida) Herbs Loblolly Pine (P. taeda) Longleaf Pine (Pinus palustris) Blazing Star (Liatris spp.) Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) Red Bay (Persea borbonia) Blue‐Eyed Grass (Sisyrinchium arenicola) Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana) Blue Star (Amsonia spp.) Red Maple (Acer Rubrum) Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa) Redbud (Cercis canadensis) Crane‐Fly Orchid (Tipularia discolor) Short‐Leaf Pine (P. echinata) Dwarf Iris (Iris verna) Scrub Pine (P. virginiana) Green‐and‐Gold (Chrysogonum virginianum) Sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum) Henbit (Lamium amplexicaule) Sweet Bay (M. virginiana) Hepatica (Hepatica americana) Tulip Tree (Liriodendron tulipifera) Jack‐In‐The‐Pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum) Turkey Oak (Q. laevis) Jointweed (Polygonum spp.) White Oak (Quercus alba) Lizard’s Tail (Saururus cernuus) Lupine (Lupinus spp.) Shrubs Mistletoe (Phoradendron serotinum) Partridge Berry (Mitchella repens) Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) Pipsissewa (Chimaphila maculate) French Mulberry (Callicarpa americana) Pucoon (Lithospermum caroliniense) Hearts‐A’Burstin With Love (Euonymus americanus) Spanish Moss (Tillandsia usneoides) Holly (Ilex spp.) Spiderwort (Tradescantia spp.) Horse Sugar (Symplocos tinctoria) Sticky -

Understory Plant Community Response to Season of Burn in Natural Longleaf Pine Forests

UNDERSTORY PLANT COMMUNITY RESPONSE TO SEASON OF BURN IN NATURAL LONGLEAF PINE FORESTS John S. Kush and Ralph S. Meldahl School of Forestry, 108 M. White Smith Hall, Auburn University, AL 36849 William D. Boyer U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station, 520 Devall Street, Auburn, AL 36849 ABSTRACT A season of burn study· was initiated in 1973 on the EscambiaExperimental Forest, near Brewton, Alabama. All study plots were established in l4-year-old longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) stands. Treatments conSisted of biennial burns in winter, spring, and summer, plus a no-burn check. Objectives of the current study were to determine composition and structure of understory plant communities after 22 years of seasonal burning, identify changes since last sampling in 1982, arid assess the structure of the communities that stabilized under each treatment regime. There were 114 species on biennial winter~burned plots, compared to 104 on spring- and summer-burned and 84 with no burning. The woody understory biomass «1 centimeter diameter at breast height) increased with all treatments compared with 1982. Grass and legume biomass increased with winter and spring burning. Forb biomass decreased across treatments. keywords: biomass, longleaf pine, Pinus palustris, plant response, prescribed fire, south Alabama, understory. Citation: Kush, 1.S., R$. Meldahl, and W.D. Boyer. 2000. Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Pages 32-39 inW Keith Moser and Cynthia F. Moser (eds.). Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture and vegetation management. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings, No. 21. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, FL. -

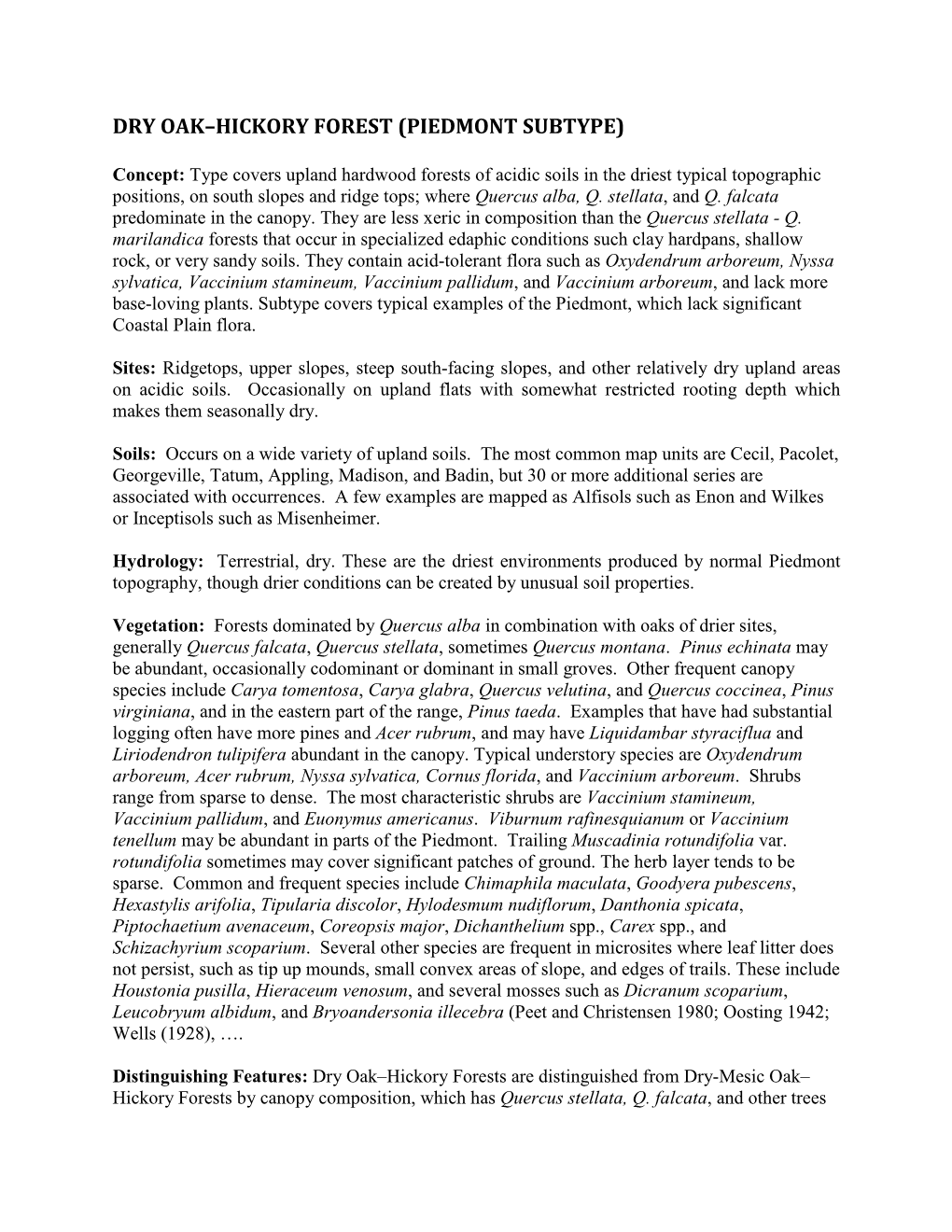

Native Plant List Trees.XLS

Lower Makefield Township Native Plant List* TREES LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE EVERGREEN Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar x x x x IIex opaca American Holly x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar x x x Picea glauca White Spruce x x x Picea pungens Blue Spruce x x x Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine x x x Pinus resinosa Red Pine x x x Pinus rigida Pitch Pine x x Pinus strobus White Pine x x x Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine x x x Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae x x x x Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock xx x DECIDUOUS Acer rubrum Red Maple x x x x x x Acer saccharinum Silver Maple x x x x Acer saccharum Sugar Maple x x x x Asimina triloba Paw-Paw x x Betula lenta Sweet Birch x x x x Betula nigra River Birch x x x x Betula populifolia Gray Birch x x x x x Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam x x x (C. tomentosa) Carya alba Mockernut Hickory x x x x Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory x x x Carya glabra Pignut Hickory x x x x x Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory x x Castanea pumila Allegheny Chinkapin xx x Celtis occidentalis Hackberry x x x x x x Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur Hawthorn x x x x Crataegus viridis Green Hawthorn x x x x Diospyros virginiana Common Persimmon x x x x Fagus grandifolia American Beech x x x x PAGE 1 Exhibit 1 TREES (cont'd) LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE DECIDUOUS (cont'd) Fraxinus americana White Ash x x x x Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash x x x x x Gleditsia triacanthos v. -

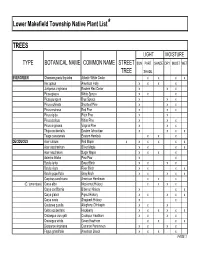

List of Approved Trees

CITY OF CAPE MAY - LIST OF APPROVED TREES COMMON NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME AESTHETIC QUALITY AND MATURE SIZE CLASS STREET OR LAWN CLASS PLANT SALT TOLERANCE ENVIRONMENTAL BENEFIT- NOTES ISA SPECIES RATING AND LIMITATIONS BIRD BENEFIT (# OF BIRDS) B AMERICAN BEECH FAGUS GRANDIFOLIA LARGE 25 50-70' BLACK OR SWEET BIRCH BETULA LENTA MEDIUM/LARGE 13 40-60' GRAY BIRCH BETULA POPULIFOLIA MEDIUM LAWN 14 20-40' YELLOW BIRCH BETULA LUTEA LARGE 13 60-80' BUTTERNUT JUGLANS CINEREAL MEDIUM/LARGE 11 40-60' C EASTERN RED CEDAR JUNIPERUS VIRGINIANA MEDIUM LAWN 32 40-50' BLACK CHERRY PRUNUS SEROTINA LARGE LAWN 53 50-80' CHERRY PRUNUS SSP MEDIUM STREET OR LAWN 42 PIN OR FIRE CHERRY P. PENSYLVANICA 42 CHOKECHERRY P. VIRGINIANA SMALL LAWN 43 20-30' (UTILITY FRIENDLY) CRAB APPLE MALUS SPP SMALL LAWN 26 15-20' (UTILITY FRIENDLY) D FLOWERING DOGWOOD CORNUS FLORIDA SMALL LAWN 34 15-30' (UTILITY FRIENDLY) E ELM ULMUS SSP LARGE LAWN 18 G SOUR GUM OR BLACK TUPELO NYSSA SLYVATICA MEDIUM STREET OR LAWN 34 30-50' SWEET GUM LIQUIDAMBER STYRACIFLUA MEDIUM/LARGE STREET OR LAWN 21 40-60' H HACKBERRY CELTIS OCCIDENTALIS MEDIUM/LARGE STREET OR LAWN 25 40-60' DWARF HACKBERRY CELTIS TENUIFOLIA 25 MOCKERNUT HICKORY CARYA TOMENTOSA LARGE 60-80' PIGNUT HICKORY CARYA GLABRA LARGE 19 70-90' SHAGBARK HICKORY CARYA OVATA LARGE 19 70-90' AMERICAN HOLLY LLEX OPACA MEDIUM LAWN 13 40-50' AMERICAN HORNBEAM CARPINUS CAROLINIANA SMALL STREET OR LAWN 10 20-35' (UTILITY FRIENDLY) M SWEET BAY MAGNOLIA MAGNOLIA VIRGINANA SMALL LAWN 10-35' RED MAPLE ACER RUBRUM MEDIUM/LARGE STREET OR LAWN 5 40-60' -

Lyonia Preserve Plant Checklist

I -1 Lyonia Preserve Plant Checklist Volusia County, Florida I, I Aceraceae (Maple) Asteraceae (Aster) Red Maple Acer rubrum • Bitterweed Helenium amarum • Blackroot Pterocaulon virgatum Agavaceae (Yucca) Blazing Star Liatris sp. B Adam's Needle Yucca filamentosa Blazing Star Liatris tenuifolia BNolina Nolina brittoniana Camphorweed Heterotheca subaxillaris Spanish Bayonet Yucca aloifolia § Cudweed Gnaphalium falcatum • Dog Fennel Eupatorium capillifolium Amaranthaceae (Amaranth) Dwarf Horseweed Conyza candensis B Cottonweed Froelichia floridana False Dandelion Pyrrhopappus carolinianus • Fireweed Erechtites hieracifolia B Anacardiaceae (Cashew) Garberia Garberia heterophylla Winged Sumac Rhus copallina Goldenaster Pityopsis graminifolia • § Goldenrod Solidago chapmanii Annonaceae (Custard Apple) Goldenrod Solidago fistulosa Flag Paw paw Asimina obovata Goldenrod Solidago spp. B • Mohr's Throughwort Eupatorium mohrii Apiaceae (Celery) BRa gweed Ambrosia artemisiifolia • Dollarweed Hydrocotyle sp. Saltbush Baccharis halimifolia BSpanish Needles Bidens alba Apocynaceae (Dogbane) Wild Lettuce Lactuca graminifolia Periwinkle Catharathus roseus • • Brassicaceae (Mustard) Aquifoliaceae (Holly) Poorman's Pepper Lepidium virginicum Gallberry Ilex glabra • Sand Holly Ilex ambigua Bromeliaceae (Airplant) § Scrub Holly Ilex opaca var. arenicola Ball Moss Tillandsia recurvata • Spanish Moss Tillandsia usneoides Arecaceae (Palm) • Saw Palmetto Serenoa repens Cactaceae (Cactus) BScrub Palmetto Sabal etonia • Prickly Pear Opuntia humifusa Asclepiadaceae -

Landscaping Near Black Walnut Trees

Selecting juglone-tolerant plants Landscaping Near Black Walnut Trees Black walnut trees (Juglans nigra) can be very attractive in the home landscape when grown as shade trees, reaching a potential height of 100 feet. The walnuts they produce are a food source for squirrels, other wildlife and people as well. However, whether a black walnut tree already exists on your property or you are considering planting one, be aware that black walnuts produce juglone. This is a natural but toxic chemical they produce to reduce competition for resources from other plants. This natural self-defense mechanism can be harmful to nearby plants causing “walnut wilt.” Having a walnut tree in your landscape, however, certainly does not mean the landscape will be barren. Not all plants are sensitive to juglone. Many trees, vines, shrubs, ground covers, annuals and perennials will grow and even thrive in close proximity to a walnut tree. Production and Effect of Juglone Toxicity Juglone, which occurs in all parts of the black walnut tree, can affect other plants by several means: Stems Through root contact Leaves Through leakage or decay in the soil Through falling and decaying leaves When rain leaches and drips juglone from leaves Nuts and hulls and branches onto plants below. Juglone is most concentrated in the buds, nut hulls and All parts of the black walnut tree produce roots and, to a lesser degree, in leaves and stems. Plants toxic juglone to varying degrees. located beneath the canopy of walnut trees are most at risk. In general, the toxic zone around a mature walnut tree is within 50 to 60 feet of the trunk, but can extend to 80 feet. -

Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2015/981 ON THE COVER Photo of the Tallapoosa River, viewed from Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Photo Courtesy of Elle Allen Natural Resource Condition Assessment Horseshoe Bend National Military Park Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR—2015/981 JoAnn M. Burkholder, Elle H. Allen, Stacie Flood, and Carol A. Kinder Center for Applied Aquatic Ecology North Carolina State University 620 Hutton Street, Suite 104 Raleigh, NC 27606 June 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner.