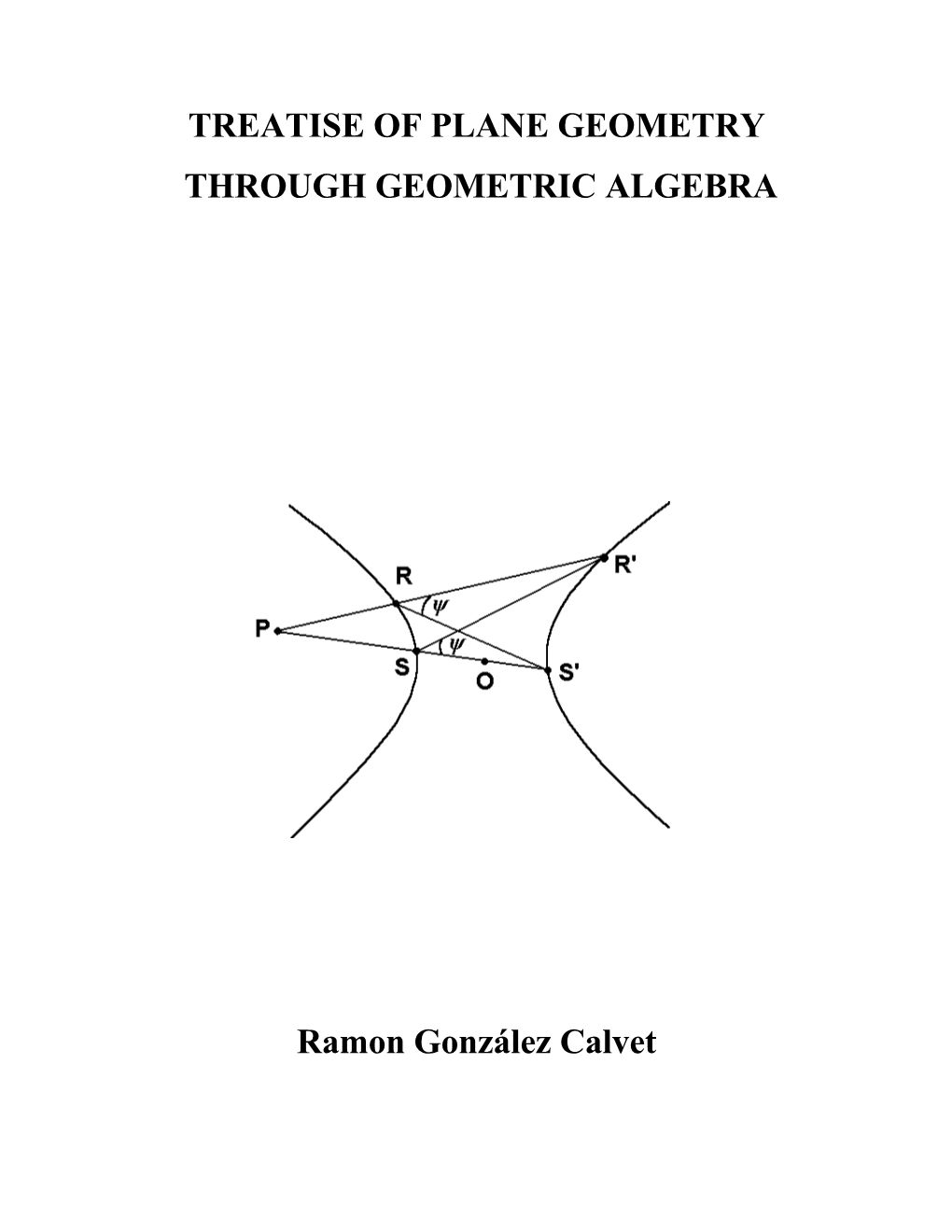

Treatise of Plane Geometry Through Geometric Algebra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geometric Algebra for Vector Fields Analysis and Visualization: Mathematical Settings, Overview and Applications Chantal Oberson Ausoni, Pascal Frey

Geometric algebra for vector fields analysis and visualization: mathematical settings, overview and applications Chantal Oberson Ausoni, Pascal Frey To cite this version: Chantal Oberson Ausoni, Pascal Frey. Geometric algebra for vector fields analysis and visualization: mathematical settings, overview and applications. 2014. hal-00920544v2 HAL Id: hal-00920544 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-00920544v2 Preprint submitted on 18 Sep 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Geometric algebra for vector field analysis and visualization: mathematical settings, overview and applications Chantal Oberson Ausoni and Pascal Frey Abstract The formal language of Clifford’s algebras is attracting an increasingly large community of mathematicians, physicists and software developers seduced by the conciseness and the efficiency of this compelling system of mathematics. This contribution will suggest how these concepts can be used to serve the purpose of scientific visualization and more specifically to reveal the general structure of complex vector fields. We will emphasize the elegance and the ubiquitous nature of the geometric algebra approach, as well as point out the computational issues at stake. 1 Introduction Nowadays, complex numerical simulations (e.g. in climate modelling, weather fore- cast, aeronautics, genomics, etc.) produce very large data sets, often several ter- abytes, that become almost impossible to process in a reasonable amount of time. -

Exploring Physics with Geometric Algebra, Book II., , C December 2016 COPYRIGHT

peeter joot [email protected] EXPLORINGPHYSICSWITHGEOMETRICALGEBRA,BOOKII. EXPLORINGPHYSICSWITHGEOMETRICALGEBRA,BOOKII. peeter joot [email protected] December 2016 – version v.1.3 Peeter Joot [email protected]: Exploring physics with Geometric Algebra, Book II., , c December 2016 COPYRIGHT Copyright c 2016 Peeter Joot All Rights Reserved This book may be reproduced and distributed in whole or in part, without fee, subject to the following conditions: • The copyright notice above and this permission notice must be preserved complete on all complete or partial copies. • Any translation or derived work must be approved by the author in writing before distri- bution. • If you distribute this work in part, instructions for obtaining the complete version of this document must be included, and a means for obtaining a complete version provided. • Small portions may be reproduced as illustrations for reviews or quotes in other works without this permission notice if proper citation is given. Exceptions to these rules may be granted for academic purposes: Write to the author and ask. Disclaimer: I confess to violating somebody’s copyright when I copied this copyright state- ment. v DOCUMENTVERSION Version 0.6465 Sources for this notes compilation can be found in the github repository https://github.com/peeterjoot/physicsplay The last commit (Dec/5/2016), associated with this pdf was 595cc0ba1748328b765c9dea0767b85311a26b3d vii Dedicated to: Aurora and Lance, my awesome kids, and Sofia, who not only tolerates and encourages my studies, but is also awesome enough to think that math is sexy. PREFACE This is an exploratory collection of notes containing worked examples of more advanced appli- cations of Geometric Algebra (GA), also known as Clifford Algebra. -

How Should the College Teach Analytic Geometry?*

1906.] THE TEACHING OF ANALYTIC GEOMETRY. 493 HOW SHOULD THE COLLEGE TEACH ANALYTIC GEOMETRY?* BY PROFESSOR HENRY S. WHITE. IN most American colleges, analytic geometry is an elective study. This fact, and the underlying causes of this fact, explain the lack of uniformity in content or method of teaching this subject in different institutions. Of many widely diver gent types of courses offered, a few are likely to survive, each because it is best fitted for some one purpose. It is here my purpose to advocate for the college of liberal arts a course that shall draw more largely from projective geometry than do most of our recent college text-books. This involves a restriction of the tendency, now quite prevalent, to devote much attention at the outset to miscellaneous graphs of purely statistical nature or of physical significance. As to the subject matter used in a first semester, one may formulate the question : Shall we teach in one semester a few facts about a wide variety of curves, or a wide variety of propositions about conies ? Of these alternatives the latter is to be preferred, for the educational value of a subject is found less in its extension than in its intension ; less in the multiplicity of its parts than in their unification through a few fundamental or climactic princi ples. Some teachers advocate the study of a wider variety of curves, either for the sake of correlation wTith physical sci ences, or in order to emphasize what they term the analytic method. As to the first, there is a very evident danger of dis sipating the student's energy ; while to the second it may be replied that there is no one general method which can be taught, but many particular and ingenious methods for special problems, whose resemblances may be understood only when the problems have been mastered. -

Greece Part 3

Greece Chapters 6 and 7: Archimedes and Apollonius SOME ANCIENT GREEK DISTINCTIONS Arithmetic Versus Logistic • Arithmetic referred to what we now call number theory –the study of properties of whole numbers, divisibility, primality, and such characteristics as perfect, amicable, abundant, and so forth. This use of the word lives on in the term higher arithmetic. • Logistic referred to what we now call arithmetic, that is, computation with whole numbers. Number Versus Magnitude • Numbers are discrete, cannot be broken down indefinitely because you eventually came to a “1.” In this sense, any two numbers are commensurable because they could both be measured with a 1, if nothing bigger worked. • Magnitudes are continuous, and can be broken down indefinitely. You can always bisect a line segment, for example. Thus two magnitudes didn’t necessarily have to be commensurable (although of course they could be.) Analysis Versus Synthesis • Synthesis refers to putting parts together to obtain a whole. • It is also used to describe the process of reasoning from the general to the particular, as in putting together axioms and theorems to prove a particular proposition. • Proofs of the kind Euclid wrote are referred to as synthetic. Analysis Versus Synthesis • Analysis refers to taking things apart to see how they work, or so you can understand them. • It is also used to describe reasoning from the particular to the general, as in studying a particular problem to come up with a solution. • This is one general meaning of analysis: a way of solving problems, of finding the answers. Analysis Versus Synthesis • A second meaning for analysis is specific to logic and theorem proving: beginning with what you wish to prove, and reasoning from that point in hopes you can arrive at the hypotheses, and then reversing the logical steps. -

Finite Projective Geometries 243

FINITE PROJECTÎVEGEOMETRIES* BY OSWALD VEBLEN and W. H. BUSSEY By means of such a generalized conception of geometry as is inevitably suggested by the recent and wide-spread researches in the foundations of that science, there is given in § 1 a definition of a class of tactical configurations which includes many well known configurations as well as many new ones. In § 2 there is developed a method for the construction of these configurations which is proved to furnish all configurations that satisfy the definition. In §§ 4-8 the configurations are shown to have a geometrical theory identical in most of its general theorems with ordinary projective geometry and thus to afford a treatment of finite linear group theory analogous to the ordinary theory of collineations. In § 9 reference is made to other definitions of some of the configurations included in the class defined in § 1. § 1. Synthetic definition. By a finite projective geometry is meant a set of elements which, for sugges- tiveness, are called points, subject to the following five conditions : I. The set contains a finite number ( > 2 ) of points. It contains subsets called lines, each of which contains at least three points. II. If A and B are distinct points, there is one and only one line that contains A and B. HI. If A, B, C are non-collinear points and if a line I contains a point D of the line AB and a point E of the line BC, but does not contain A, B, or C, then the line I contains a point F of the line CA (Fig. -

New Foundations for Geometric Algebra1

Text published in the electronic journal Clifford Analysis, Clifford Algebras and their Applications vol. 2, No. 3 (2013) pp. 193-211 New foundations for geometric algebra1 Ramon González Calvet Institut Pere Calders, Campus Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Cerdanyola del Vallès, Spain E-mail : [email protected] Abstract. New foundations for geometric algebra are proposed based upon the existing isomorphisms between geometric and matrix algebras. Each geometric algebra always has a faithful real matrix representation with a periodicity of 8. On the other hand, each matrix algebra is always embedded in a geometric algebra of a convenient dimension. The geometric product is also isomorphic to the matrix product, and many vector transformations such as rotations, axial symmetries and Lorentz transformations can be written in a form isomorphic to a similarity transformation of matrices. We collect the idea Dirac applied to develop the relativistic electron equation when he took a basis of matrices for the geometric algebra instead of a basis of geometric vectors. Of course, this way of understanding the geometric algebra requires new definitions: the geometric vector space is defined as the algebraic subspace that generates the rest of the matrix algebra by addition and multiplication; isometries are simply defined as the similarity transformations of matrices as shown above, and finally the norm of any element of the geometric algebra is defined as the nth root of the determinant of its representative matrix of order n. The main idea of this proposal is an arithmetic point of view consisting of reversing the roles of matrix and geometric algebras in the sense that geometric algebra is a way of accessing, working and understanding the most fundamental conception of matrix algebra as the algebra of transformations of multiple quantities. -

On the Constructibility of the Axes of an Ellipsoid

ON THE CONSTRUCTIBILITY OF THE AXES OF AN ELLIPSOID. THE CONSTRUCTION OF CHASLES IN PRACTICE AKOS´ G.HORVATH´ AND ISTVAN´ PROK Dedicated to the memory of the teaching of Descriptive Geometry in BME Faculty of Mechanical Engineering Abstract. In this paper we discuss Chasles’s construction on ellipsoid to draw the semi-axes from a complete system of conjugate diameters. We prove that there is such situation when the construction is not planar (the needed points cannot be constructed with compasses and ruler) and give some others in which the construction is planar. 1. Introduction Who interested in conics know the construction of Rytz, namely a construction which determines the axes of an ellipse from a pair of conjugate diameters. Contrary to this very few mathematicians know that in the first half of the nineteens century Chasles (see in [1]) gave a construction in space to the analogous problem. The only reference which we found in English is also in an old book written by Salmon (see in [6]) on the analytic geometry of the three-dimensional space. In [2] the author extracted this analytic method to prove some results on the quadric of n-dimensional space. However, in practice this construction cannot be done using compasses and ruler only as we will see in present paper (Statement 4). On the other hand those steps of the construction which are planar constructions we can draw by descriptive geometry (see the figures in this article). 2. Basic properties The proof of the statements of this section can be found in [2]. -

Notices of the American Mathematical Society 35 Monticello Place, Pawtucket, RI 02861 USA American Mathematical Society Distribution Center

ISSN 0002-9920 Notices of the American Mathematical Society 35 Monticello Place, Pawtucket, RI 02861 USA Society Distribution Center American Mathematical of the American Mathematical Society February 2012 Volume 59, Number 2 Conformal Mappings in Geometric Algebra Page 264 Infl uential Mathematicians: Birth, Education, and Affi liation Page 274 Supporting the Next Generation of “Stewards” in Mathematics Education Page 288 Lawrence Meeting Page 352 Volume 59, Number 2, Pages 257–360, February 2012 About the Cover: MathJax (see page 346) Trim: 8.25" x 10.75" 104 pages on 40 lb Velocity • Spine: 1/8" • Print Cover on 9pt Carolina AMS-Simons Travel Grants TS AN GR EL The AMS is accepting applications for the second RAV T year of the AMS-Simons Travel Grants program. Each grant provides an early career mathematician with $2,000 per year for two years to reimburse travel expenses related to research. Sixty new awards will be made in 2012. Individuals who are not more than four years past the comple- tion of the PhD are eligible. The department of the awardee will also receive a small amount of funding to help enhance its research atmosphere. The deadline for 2012 applications is March 30, 2012. Applicants must be located in the United States or be U.S. citizens. For complete details of eligibility and application instructions, visit: www.ams.org/programs/travel-grants/AMS-SimonsTG Solve the differential equation. t ln t dr + r = 7tet dt 7et + C r = ln t WHO HAS THE #1 HOMEWORK SYSTEM FOR CALCULUS? THE ANSWER IS IN THE QUESTIONS. -

Essential Concepts of Projective Geomtry

Essential Concepts of Projective Geomtry Course Notes, MA 561 Purdue University August, 1973 Corrected and supplemented, August, 1978 Reprinted and revised, 2007 Department of Mathematics University of California, Riverside 2007 Table of Contents Preface : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : i Prerequisites: : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : :iv Suggestions for using these notes : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : :v I. Synthetic and analytic geometry: : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : :1 1. Axioms for Euclidean geometry : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 1 2. Cartesian coordinate interpretations : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 2 2 3 3. Lines and planes in R and R : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 3 II. Affine geometry : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 7 1. Synthetic affine geometry : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 7 2. Affine subspaces of vector spaces : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : 13 3. Affine bases: : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : : :19 4. Properties of coordinate -

Geometric Reasoning with Invariant Algebras

Geometric Reasoning with Invariant Algebras Hongbo Li [email protected] Key Laboratory of Mathematics Mechanization Academy of Mathematics and Systems Science Chinese Academy of Sciences Beijing 100080, P. R. China Abstract: Geometric reasoning is a common task in Mathematics Education, Computer-Aided Design, Com- puter Vision and Robot Navigation. Traditional geometric reasoning follows either a logical approach in Arti¯cial Intelligence, or a coordinate approach in Computer Algebra, or an approach of basic geometric invariants such as areas, volumes and distances. In algebraic approaches to geometric reasoning, geometric interpretation is needed for the result after algebraic manipulation, but in general this is a di±cult task. It is hoped that more advanced geometric invariants can make some contribution to the problem. In this paper, a hierarchical framework of invariant algebras is introduced for algebraic manipulation of geometric problems. The bottom level is the algebra of basic geometric invariants, and the higher levels are more complicated invariants. High level invariants can keep more geometric nature within algebraic structure. They are bene¯cial to geometric explanation but more di±cult to handle with than low level ones. This paper focuses on geometric computing at high invariant levels, for both automated theorem proving and new theorem discovering. Using the new techniques developed in recent years for hierarchical invariant algebras, better geometric results can be obtained from algebraic computation, in addition to more e±cient algebraic manipulation. 1 Background: Geometric Invariants What is geometric computing? Computing is an algebraic thing. If the objects involved are geometric, then in some suitable algebraic framework, the geometric problem is translated into an algebraic one, and an algebraic result is obtained by computation [18]. -

11.-HYPERBOLA-THEORY.Pdf

12. HYPERBOLA 1. INTRODUCTION A hyperbola is the locus of a point which moves in the plane in such a way that Z the ratio of its distance from a fixed point in the same plane to its distance X’ P from a fixed line is always constant which is always greater than unity. M The fixed point is called the focus, the fixed line is called the directrix. The constant ratio is generally denoted by e and is known as the eccentricity of the Directrix hyperbola. A hyperbola can also be defined as the locus of a point such that S (focus) the absolute value of the difference of the distances from the two fixed points Z’ (foci) is constant. If S is the focus, ZZ′ is the directrix and P is any point on the hyperbola as show in figure. Figure 12.1 SP Then by definition, we have = e (e > 1). PM Note: The general equation of a conic can be taken as ax22+ 2hxy + by + 2gx + 2fy += c 0 This equation represents a hyperbola if it is non-degenerate (i.e. eq. cannot be written into two linear factors) ahg ∆ ≠ 0, h2 > ab. Where ∆=hb f gfc MASTERJEE CONCEPTS 1. The general equation ax22+ 2hxy + by + 2gx + 2fy += c 0 can be written in matrix form as ahgx ah x x y + 2gx + 2fy += c 0 and xy1hb f y = 0 hb y gfc1 Degeneracy condition depends on the determinant of the 3x3 matrix and the type of conic depends on the determinant of the 2x2 matrix. -

Attoclock Ultrafast Timing of Inversive Chord-Contact Dynamics

Attoclock Ultrafast Timing of Inversive Chord-Contact Dynamics - A Spectroscopic FFT-Glimpse onto Harmonic Analysis of Gravitational Waves - Walter J. Schempp Lehrstuhl f¨urMathematik I Universit¨atSiegen 57068 Siegen, Germany [email protected] According to Bohr's model of the hydrogen atom, it takes about 150 as for an electron in the ground state to orbit around the atomic core. Therefore, the attosecond (1 as = 10−18s) is the typical time scale for Bloch wave packet dynamics operating at the interface of quantum field theory and relativity theory. Attoclock spectroscopy is mathematically dominated by the spectral dual pair of spin groups with the commuting action of the stabilized symplectic spinor quantization (Mp(2; R); PSO(1; 3; R)) In the context of the Mp(2; R) × PSO(1; 3; R) module structure of the complex Schwartz space 2 2 ∼ S(R ⊕ R ) = S(C ⊕ C) of quantum field theory, the metaplectic Lie group Mp(2; R) is the ∼ two-sheeted covering group Sp(2f ; R) of the symplectic group Sp(2; R) = SL(2; R), where the ∼ special linear group SL(2; R) is a simple Lie group, and the two-cycle rotation group SO(2f ; R) = U(1e ; C) is a maximal compact subgroup of Mp(2; R). The two-fold hyperbolically, respectively ∼ elliptically ruled conformal Lie group SU(1; 1; C) is conjugate to SL(2; R) = Spin(1; 2; R) in the ∼ ∼ complexification SL(2; C) = Spin(1; 3; R); the projective Lorentz-M¨obiusgroup PSO(1; 3; R) = ∼ PSL(2; C) = SL(2; C)=(Z2:id) represents a semi-simple Lie group which is isomorphic to the "+ four-dimensional proper orthochroneous Lorentz group L4 of relativity theory.