Using Pahoehoe Crust Growth Rates to Constrain Lava Channel Formation Events and Timing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volcanism on Mars

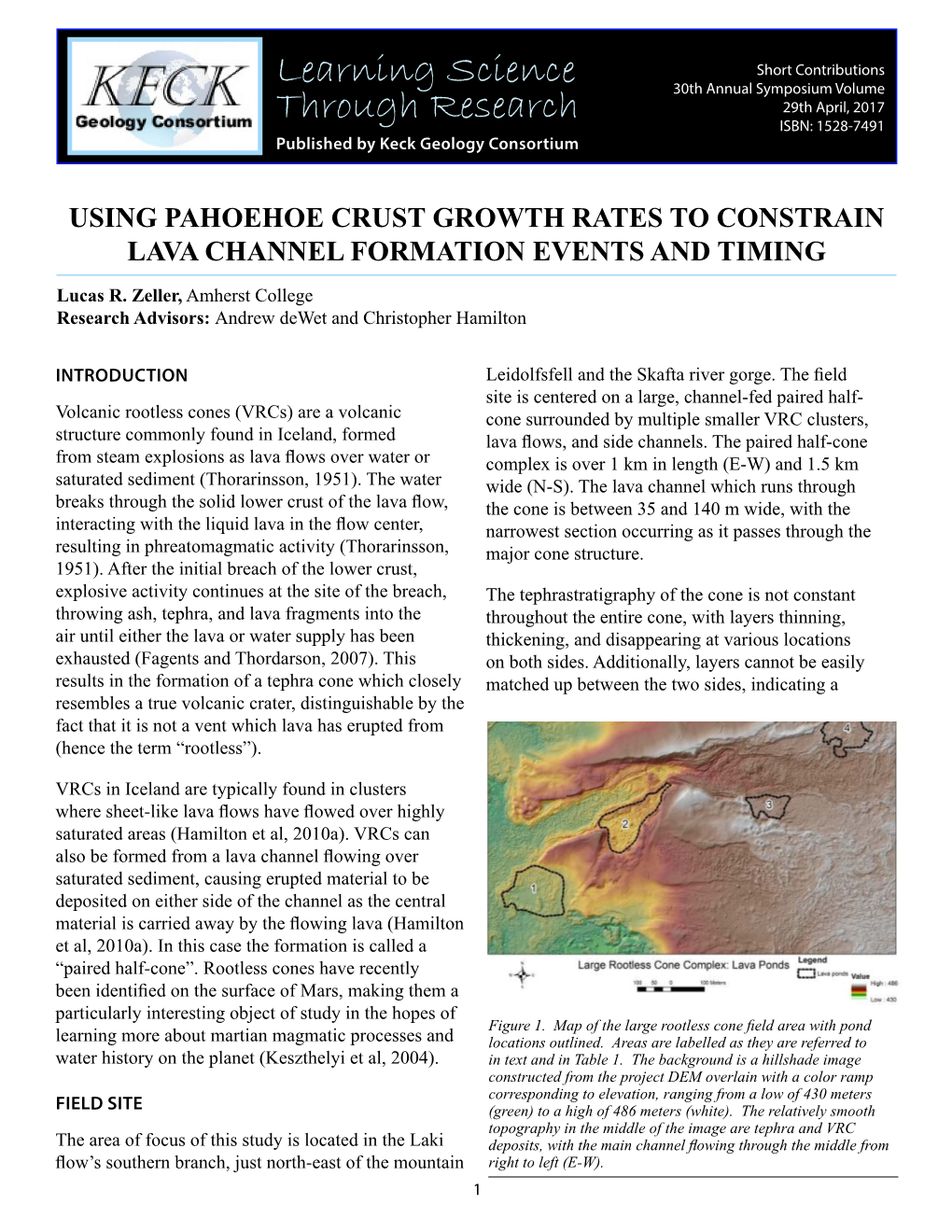

Author's personal copy Chapter 41 Volcanism on Mars James R. Zimbelman Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA William Brent Garry and Jacob Elvin Bleacher Sciences and Exploration Directorate, Code 600, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, USA David A. Crown Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ, USA Chapter Outline 1. Introduction 717 7. Volcanic Plains 724 2. Background 718 8. Medusae Fossae Formation 725 3. Large Central Volcanoes 720 9. Compositional Constraints 726 4. Paterae and Tholi 721 10. Volcanic History of Mars 727 5. Hellas Highland Volcanoes 722 11. Future Studies 728 6. Small Constructs 723 Further Reading 728 GLOSSARY shield volcano A broad volcanic construct consisting of a multitude of individual lava flows. Flank slopes are typically w5, or less AMAZONIAN The youngest geologic time period on Mars identi- than half as steep as the flanks on a typical composite volcano. fied through geologic mapping of superposition relations and the SNC meteorites A group of igneous meteorites that originated on areal density of impact craters. Mars, as indicated by a relatively young age for most of these caldera An irregular collapse feature formed over the evacuated meteorites, but most importantly because gases trapped within magma chamber within a volcano, which includes the potential glassy parts of the meteorite are identical to the atmosphere of for a significant role for explosive volcanism. Mars. The abbreviation is derived from the names of the three central volcano Edifice created by the emplacement of volcanic meteorites that define major subdivisions identified within the materials from a centralized source vent rather than from along a group: S, Shergotty; N, Nakhla; C, Chassigny. -

Explosive Lava‐Water Interactions in Elysium Planitia, Mars: Geologic and Thermodynamic Constraints on the Formation of the Tartarus Colles Cone Groups Christopher W

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 115, E09006, doi:10.1029/2009JE003546, 2010 Explosive lava‐water interactions in Elysium Planitia, Mars: Geologic and thermodynamic constraints on the formation of the Tartarus Colles cone groups Christopher W. Hamilton,1 Sarah A. Fagents,1 and Lionel Wilson2 Received 16 November 2009; revised 11 May 2010; accepted 3 June 2010; published 16 September 2010. [1] Volcanic rootless constructs (VRCs) are the products of explosive lava‐water interactions. VRCs are significant because they imply the presence of active lava and an underlying aqueous phase (e.g., groundwater or ice) at the time of their formation. Combined mapping of VRC locations, age‐dating of their host lava surfaces, and thermodynamic modeling of lava‐substrate interactions can therefore constrain where and when water has been present in volcanic regions. This information is valuable for identifying fossil hydrothermal systems and determining relationships between climate, near‐surface water abundance, and the potential development of habitable niches on Mars. We examined the western Tartarus Colles region (25–27°N, 170–171°E) in northeastern Elysium Planitia, Mars, and identified 167 VRC groups with a total area of ∼2000 km2. These VRCs preferentially occur where lava is ∼60 m thick. Crater size‐frequency relationships suggest the VRCs formed during the late to middle Amazonian. Modeling results suggest that at the time of VRC formation, near‐surface substrate was partially desiccated, but that the depth to the midlatitude ice table was ]42 m. This ground ice stability zone is consistent with climate models that predict intermediate obliquity (∼35°) between 75 and 250 Ma, with obliquity excursions descending to ∼25–32°. -

Identification of Volcanic Rootless Cones, Ice Mounds, and Impact 3 Craters on Earth and Mars: Using Spatial Distribution As a Remote 4 Sensing Tool

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 111, XXXXXX, doi:10.1029/2005JE002510, 2006 Click Here for Full Article 2 Identification of volcanic rootless cones, ice mounds, and impact 3 craters on Earth and Mars: Using spatial distribution as a remote 4 sensing tool 1 1 1 2 3 5 B. C. Bruno, S. A. Fagents, C. W. Hamilton, D. M. Burr, and S. M. Baloga 6 Received 16 June 2005; revised 29 March 2006; accepted 10 April 2006; published XX Month 2006. 7 [1] This study aims to quantify the spatial distribution of terrestrial volcanic rootless 8 cones and ice mounds for the purpose of identifying analogous Martian features. Using a 9 nearest neighbor (NN) methodology, we use the statistics R (ratio of the mean NN distance 10 to that expected from a random distribution) and c (a measure of departure from 11 randomness). We interpret R as a measure of clustering and as a diagnostic for 12 discriminating feature types. All terrestrial groups of rootless cones and ice mounds are 13 clustered (R: 0.51–0.94) relative to a random distribution. Applying this same 14 methodology to Martian feature fields of unknown origin similarly yields R of 0.57–0.93, 15 indicating that their spatial distributions are consistent with both ice mound or rootless 16 cone origins, but not impact craters. Each Martian impact crater group has R 1.00 (i.e., 17 the craters are spaced at least as far apart as expected at random). Similar degrees of 18 clustering preclude discrimination between rootless cones and ice mounds based solely on 19 R values. -

The Chain of Rootless Cones in Chryse Planitia on Mars. L

52nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2021 (LPI Contrib. No. 2548) 2740.pdf THE CHAIN OF ROOTLESS CONES IN CHRYSE PLANITIA ON MARS. L. Czechowski1, N. Zalewska2, A. Zambrowska2, M. Ciążela3, P. Witek4, J. Kotlarz5, 1University of Warsaw, Faculty of Physics, Institute of Geophysics, ul. Pasteura 5, 02-093 Warszawa, Poland, [email protected], tel. +48 22 55 32 003, 2Space Research Center PAS, ul. Bartycka 18 A, 00-716 Warszawa, Poland, 3Space Research Center PAS, ul. Bartycka 18 A, 00-716 Warszawa, Poland (presently Institute of Geological Sciences, PAS. ul. Twarda 51/55, 00-818 Warszawa, Poland). 4Copernicus Science Centre, ul. Wybrzeże Kościuszkowskie 20, 00-390 Warszawa, Poland, 5Łukasiewicz Research Network - Institute of Aviation, Al. Krakowska 110/114, 02-256 Warszawa, Poland. Introduction: We consider a small region in Chryse The material ejected by the explosion covered the valley Planitia ( ~38o14′ N, ~319o25’ E) where several chains and the slopes of the neighboring hills. (iii) Later, the of cones are found – Fig. 1. The cones height are ~10- lower structures (including the valley floor) were 20 m. The considered region is at the boundary of covered with fine aeolian sediments. smooth plain on west (AHcs) and complex unit (AHcc) To test this hypothesis, we computed the apparent on east. The small region (HNck) in north-west corner thermal inertia in this area. is the “older knobby material” – [1], where AH means Amazonian-Hesperian, and HN - Hesperian-Noachian. The region is covered by lacustrine deposits. Note also possible lava flows (in HNck). Small cones are common on Mars. Many cones form chains several kilometers in length. -

Why Rootless Cone Is Ubiquitous on the Martian Surface? MIS31-02

MIS31-02 JpGU-AGU Joint Meeting 2020 Why rootless cone is ubiquitous on the martian surface? *Kei Kurita1, Rina Noguchi2, Aika K Kurokawa3 1. ERI,The University of Tokyo, 2. JAXA, 3. NIED Rootless eruption is one type of magma-water interactions. They are quite rare in the terrestrial environment while water is a ubiquitous component on the surface. On the other hand enormous numbers of rootless cones are identified on the martian surface. What is the essential difference between terrestrial environments and the martian ones? This is a key question of our stating point of the research. As for the formation mechanism of rootless eruption there also exists another enigma. When hot lava flows into a wet region the lava heats up water to boiling which induces explosion. But different from other types of magma-water interactions explosion seems to continue for a while in a somehow controlled fashion to form cinder cones. The main controlling factor is still unknown. In Hawaii Island over hundreds lava flows enter the sea to meet water but only a few rootless cones were formed. Some unspecified conditions are necessary fo the formation. Noguchi et al (2016) investigates the morphometry of rootless cones in comparison with that of scoria cone and maar. In the diagram of crater diameter vs ejecta volume rootless cones locate between scoria cones and maars. Based on this we can estimate the magnitude of explosivity but above mentioned enigmas still remain unanswered. To explore keys to the enigmas about rootless eruption we conducted a comparative study on the internal structure of vesiculated pyroclasts at between rootless cones and scoria cones. -

Analog Experiment for Rootless Cone Eruption

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 11, EPSC2017-791-1, 2017 European Planetary Science Congress 2017 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2017 Analog Experiment for Rootless Cone Eruption R.Noguchi (1), A.Hamada (2),A.Suzuki(3) and K. Kurita (4) (1) Volcanic Fluid Research Center,Tokyo Institute of Technology,Japan, (2) Central Research Inst. of Electrical Power Industry,Japan,(3) JAXA,Japan.(4) ERI,University of Tokyo, Japan ([email protected]) Abstract 2. Experiments The basic experimental framework to simulate the Rootless cone is one of peculiar types of pyroclas- rootless eruption utilizes the reaction of thermal de- tic cones, which is formed by magma-water interac- composition of sodium bicarbonate solution by touch- tion when hot lavas flow into water-logged regions. ing high temperature material, which induces vesicu- Though the occurrence on the Earth is quite limited lation of CO2 gas. The experimental procedure is as large numbers of small cones on Mars are suspected follows; we put a mixture of sodium bicarbonate pow- to be rootless cones. Identification of rootless cone is der and sugar syrup in a container at room tempera- crucially important in the characterization of terrane ture. The mass fraction of the sodium bicarbonate is origin.To explore the formation mechanism we con- changed 0 to 100 % . The viscosity of the mixture ducted a series of analog experiment. layer depends on the mass fraction. Heated condensed sugar syrup(T 130◦) is poured at the top of the ∼ mixture layer. When the heated sugar syrup gradually sinks as Rayleigh-Taylor Instability the mixture layer 1. -

Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Iceland (IES) Jarðvísindastofnun

Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Iceland (IES) Jarðvísindastofnun Háskólans (JH) Universitetets Geovidenskabelige Institut (UGI) Structure, research activities and vision A report in preparation of strategic review April 2006 2 Contents 1. Mission statement 2 2. Establishment of the Institute of Earth Sciences 3 3. External framework of the Institute 3 4. Finances 6 5. Internal structure of the Institute 7 6. The Institute’s staff 9 7. Institutes role and performance 11 7.1. Teaching 11 7.2. Research 13 7.3. Research groups 14 7.4. Research Programmes 31 7.5. Research productivity 36 7.6. International research projects 38 7.7. Outreach 38 8. Status 39 9. Future 40 10. Publication list 41 Appendix I 60 Appendix II 62 Appendix III 68 1. Mission Statement The Institute of Earth Sciences (IES) is dedicated to academic research and graduate studies in the Earth sciences. The institute is engaged in research in a variety of geoscientific and environmental disciplines. Our main focus is on the unique geological features of the Iceland region. We seek to: • Advance our understanding of physical and chemical Earth processes operating within the Iceland region by reading records of the past and recording presently active processes, thus preparing for the future. • Maintain a flexible, multi-disciplinary and collaborative approach to research and higher education. • Apply earth science understanding to the needs of society and the economy. • Provide an organization that nurtures creativity and innovation, and secures the essential resources to sustain these activities. 3 2. Establishment of the Institute of Earth Sciences The new institute was formed in July 2004 by merging the Nordic Volcanological Institute with the Geology and Geophysics sections of the Science Institute of the University of Iceland, along with a part of the teaching staff from the Department of Geology and Geography and the Department of Physics within the Faculties of Science of the University of Iceland. -

Plenary Session Friday August 18, 2017. 8:30 AM - 10:30 AM OCC Oregon Ballroom 201-203

Friday, August 18 Plenary Session Friday August 18, 2017. 8:30 AM - 10:30 AM OCC Oregon Ballroom 201-203 Vickie McConnell Interfacing Science with Government: You Don’t Always Get What You Want Interfacing with the Public: Lessons Learned from 30 Years of Science Messaging at Mount St. Peter Frenzen Helens ME51A: II.4 Experimental volcanology: from magma generation to the transport and emplacement of pyroclastic materials II Friday August 18, 2017. 10:30 AM - 12:30 PM Room A107-109 Abstract Number Time Authors Title ME51A-1 10:30 AM - Alessandro Vona, Andrea Di Piazza, Eugenio Nicotra, Claudia The compleX rheology of megacryst-rich magmas (invited) 10:45 AM Romano, Marco Viccaro, Guido Giordano 10:45 AM - Ikuro Sumita, Nao Yasuda, Moe Mizuno, Heiko Woith, EXperiments on shaking-induced fluidization in a liquid-immersed granular medium : ME51A-2 11:00 AM Eleonora Rivalta implications for triggering eruptions Rebecca Coats, Biao Cai, Jackie E Kendrick, Paul A Wallace, 11:00 AM - Taka Miwa, Adrian J Hornby, James D Ashworth, FeliX W von ME51A-3 An eXperimental investigation into magma rheology using natural and analogue materials 11:15 AM Aulock, Peter D Lee, Jose Godinho, Yan Lavallée, Robert C Atwood ME51A-4 11:15 AM - James Gardner, Fabian Wadsworth, Edward Llewellin, James Sintering of Ash Under Conduit Conditions: EXperiments and Implications for the Longevity of (invited) 11:30 AM Watkins, Jason Coumans Tuffisite Fractures Does lava remember its own thermal history? A new eXperimental approach to investigate 11:30 AM - Arianna Soldati, -

Rootless Cones on Mars Indicating the Presence of Shallow Equatorial Ground Ice in Recent Times

Edinburgh Research Explorer Rootless cones on Mars indicating the presence of shallow equatorial ground ice in recent times Citation for published version: Lanagan, PD, McEwen, AS, Keszthelyi, LP & Thordarson, T 2001, 'Rootless cones on Mars indicating the presence of shallow equatorial ground ice in recent times', Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 28, no. 12, pp. 2365-2367. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GL012932 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1029/2001GL012932 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Geophysical Research Letters Publisher Rights Statement: Published in Geophysical Research Letters by the American Geophysical Union (2001) General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCHLETTERS, VOL. 28, NO. 12, PAGES2365-2367, JUNE 15,2001 Rootless cones on Mars indicating the presence of shallow equatorial ground ice in recent times Peter D. Lanagan, Alfred S. McEwen, Laszlo P. Kesztheiyi Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona Thorvaldur Thordarson Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, Hawaii Abstract. -

Evidence of Volcanic and Glacial Activity in Chryse and Acidalia Planitiae, Mars ⇑ Sara Martínez-Alonso A, , Michael T

Icarus 212 (2011) 597–621 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Evidence of volcanic and glacial activity in Chryse and Acidalia Planitiae, Mars ⇑ Sara Martínez-Alonso a, , Michael T. Mellon b, Maria E. Banks c, Laszlo P. Keszthelyi d, Alfred S. McEwen e, The HiRISE Team a Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0399, USA b Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0392, USA c Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560, USA d US Geological Survey, Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA e Lunar and Planetary Lab, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA article info abstract Article history: Chryse and Acidalia Planitiae show numerous examples of enigmatic landforms previously interpreted to Received 10 November 2008 have been influenced by a water/ice-rich geologic history. These landforms include giant polygons Revised 30 November 2010 bounded by kilometer-scale arcuate troughs, bright pitted mounds, and mesa-like features. To investigate Accepted 5 January 2011 the significance of the last we have analyzed in detail the region between 60°N, 290°E and 10°N, 360°E Available online 13 January 2011 utilizing HiRISE (High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment) images as well as regional-scale data for context. The mesas may be analogous to terrestrial tuyas (emergent sub-ice volcanoes), although defin- Keywords: itive proof has not been identified. We also report on a blocky unit and associated landforms (drumlins, Geological processes eskers, inverted valleys, kettle holes) consistent with ice-emplaced volcanic or volcano-sedimentary Mars Mars, Surface flows. -

If Lava Mingled with Ground Ice on Mars Written by Linda M.V

PSR Discoveries: Rootless cones on Mars http://www.psrd.hawaii.edu/June01/lavaIceMars.html posted June 26, 2001 If Lava Mingled with Ground Ice on Mars Written by Linda M.V. Martel Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology Clusters of small cones on the lava plains of Mars have caught the attention of planetary geologists for years for a simple and compelling reason: ground ice. These cones look like volcanic rootless cones found on Earth where hot lava flows over wet surfaces such as marshes, shallow lakes or shallow aquifers. Steam explosions fragment the lava into small pieces that fall into cone-shaped debris piles. Peter Lanagan, Alfred McEwen, Laszlo Keszthelyi (University of Arizona), and Thorvaldur Thordarson (University of Hawai`i) recently identified groups of cones in the equatorial region of Mars using new high-resolution Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) images. They report that the Martian cones have the same appearance, size, and geologic setting as rootless cones found in Iceland. If the Martian and terrestrial cones formed in the same way, then the Martian cones mark places where ground ice or groundwater existed at the time the lavas surged across the surface, estimated to be less than 10 million years ago, and where ground ice may still be today. Reference: Lanagan, P.D., A. S. McEwen, L. P. Keszthelyi, and T. Thordarson (2001) Rootless cones on Mars indicating the presence of shallow equatorial ground ice in recent times, Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 28, p. 2365-2368. Location and Description of Martian Cones Cone-shaped structures on the Martian volcanic plains were first identified and interpreted as rootless cones in the 1970s with Viking imagery. -

Some Simple Models for Rootless Cone Formation on Mars

Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVI (2005) 1914.pdf SOME SIMPLE MODELS FOR ROOTLESS CONE FORMATION ON MARS. L. Keszthelyi1, 1Astrogeology Team, U.S. Geological Survey, 2255 N. Gemini Dr., Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA. Introduction: Volcanism provides a unique tool to that the permeability of the substrate is a key sound for water in Mars’ geologic past. The interac- parameter controlling the ability of steam to tion between molten lava and surface and ground accumulate. On low permeability bedrock, even water produces a range of morphologic features on steam generated tens of meters below the surface Earth. Many of these features are interpreted to exist could not escape. However, for values appropriate on Mars. Rootless cones (a.k.a. pseudocraters) have for regolith and aeolian sands, the desiccated layer been reported in a number of locations on Mars and can be no more than a few tens of centimeters thick. interpreted to be the result of explosive interaction This result is in contrast with previous studies that between the liquid lava and groundwater/ice [1-7]. have suggested that rootless cones could form with The enigmatic ring structures seen in Athabasca ground ice several meters below the surface [6,7,11]. Valles may have formed by relatively gentle lava- Figure 1. Diagram of the geometry of the simple groundwater interaction [8]. Mesas-like features in steam accumulation model. several areas of Mars are interpreted as constructional features formed by lava erupted under ice and/or water [2,9-10]. However, rootless cones remain the feature most often and definitively cited as evidence of lava-water interaction on Mars.