Leatherback Sea Turtle Dermochelys Coriacea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Are Biologicals Smart Mole Cricket Control?

Are biologicals smart mole cricket control? by HOWARD FRANK / University of Florida ost turf managers try to control mole faster than the biopesticides, but the biopesticides cricket pests with a bait, or granules or affect a narrower range of non-target organisms and liquid containing something that kills are more environmentally acceptable. The "biora- them. That "something" may be chemi- tional" chemicals are somewhere in between, be- M cause they tend to work more slowly than the tradi- cal materials (a chemical pesticide) or living biologi- cal materials (a biopesticide). tional chemicals, and to have less effect on animals Some of the newer chemical materials, called other than insects. "biorationals," are synthetic chemicals that, for ex- Natives not pests ample, mimic the action of insects' growth hor- The 10 mole cricket species in the U.S. and its mones to interfere with development. territories (including Puerto Rico and the Virgin Is- The biological materials may be insect-killing ne- lands) differ in appearance, distribution, behavior matodes (now available commercially) or fungal or and pest status. bacterial pathogens (being tested experimentally). In fact, the native mole crickets are not pests. These products can be placed exactly where they Our pest mole crickets are immigrant species. are needed. In general, the chemical pesticides work The three species that arouse the ire of turf man- agers in the southeastern states all belong Natural enemies to the genus Scapteriscus. They came from Introducing the specialist natural ene- South America, arriving at the turn of the mies from South America to the southeast- century in ships' ballast. -

Texas Tortoise

FOR MORE INFORMATION ON THE TEXAS TORTOISE, CONTACT: ∙ TPWD: 800-792-1112 OF THE FOUR SPECIES OF TORTOISES FOUND http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/ IN NORTH AMERICA, THE TEXAS TORTOISE TEXAS ∙ Gulf Coast Turtle and Tortoise Society: IS THE ONLY ONE FOUND IN TEXAS. 866-994-2887 http://www.gctts.org/ THE TEXAS TORTOISE CAN BE FOUND IF YOU FIND A TEXAS TORTOISE THROUGHOUT SOUTHERN TEXAS AS WELL AS (OUT OF HABITAT), CONTACT: TORTOISE ∙ TPWD Law Enforcement TORTOISE NORTHEASTERN MEXICO. ∙ Permitted rehabbers in your area http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/huntwild/wild/rehab/ GOPHERUS BERLANDIERI UNFORTUNATELY EVERYTHING THERE ARE MANY THREATS YOU NEED TO KNOW TO THE SURVIVAL OF THE ABOUT THE STATE’S ONLY TEXAS TORTOISE: NATIVE TORTOISE HABITAT LOSS | ILLEGAL COLLECTION & THE THREATS IT FACES ROADSIDE MORTALITIES | PREDATION EXOTIC PATHOGENS TexasTortoise_brochure_V3.indd 1 3/28/12 12:12 PM COUNTIES WHERE THE TEXAS TORTOISE IS LISTED THE TEXAS TORTOISE (Gopherus berlandieri) is the smallest of the North American tortoises, reaching a shell length of about TEXAS TORTOISE AS A THREATENED SPECIES 8½ inches (22cm). The Texas tortoise can be distinguished CAN BE FOUND IN THE STATE OF TEXAS AND THEREFORE from other turtles found in Texas by its cylindrical and IS PROTECTED BY STATE LAW. columnar hind legs and by the yellow-orange scutes (plates) on its carapace (upper shell). IT IS ILLEGAL TO COLLECT, POSSESS, OR HARM A TEXAS TORTOISE. PENALTIES CAN INCLUDE PAYING A FINE OF Aransas, Atascosa, Bee, Bexar, Brewster, $273.50 PER TORTOISE. Brooks, Calhoun, Cameron, De Witt, Dimmit, Duval, Edwards, Frio, Goliad, Gonzales, Guadalupe, Hidalgo, Jackson, Jim Hogg, Jim Wells, Karnes, Kenedy, Kinney, Kleberg, La Salle, Lavaca, Live Oak, Matagorda, Maverick, McMullen, Medina, Nueces, WHAT SHOULD YOU Refugio, San Patricio, Starr, Sutton, Terrell, Uvalde, Val Verde, Victoria, Webb, Willacy, DO IF YOU FIND A Wilson, Zapata, Zavala TEXAS TORTOISE? THE TEXAS TORTOISE IS THE SMALLEST IN THE WILD AN INDIVIDUAL TEXAS TORTOISE LEAVE IT ALONE. -

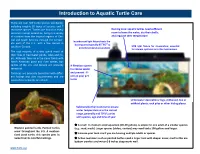

Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care

Mississippi Map Turtle Introduction to Aquatic Turtle Care There are over 300 turtle species worldwide, including roughly 60 types of tortoise and 7 sea turtle species. Turtles are found on every Basking area: aquatic turtles need sufficient continent except Antarctica, living in a variety room to leave the water, dry their shells, of climates from the tropical regions of Cen- and regulate their temperature. tral and South America through the temper- Incandescent light fixture heats the ate parts of the U.S., with a few species in o- o) basking area (typically 85 95 to UVB light fixture for illumination; essential southern Canada. provide temperature gradient for vitamin synthesis in turtles held indoors The vast majority of turtles spend much of their lives in freshwater ponds, lakes and riv- ers. Although they are in the same family with North American pond and river turtles, box turtles of the U.S. and Mexico are primarily A filtration system terrestrial. to remove waste Tortoises are primarily terrestrial with differ- and prevent ill- ent habitat and diet requirements and are ness in your pet covered in a separate care sheet. turtle Underwater decorations: logs, driftwood, live or artificial plants, rock piles or other hiding places. Submersible thermometer to ensure water temperature is in the correct range, generally mid 70osF; varies with species, age and time of year A small to medium-sized aquarium (20-29 gallons) is ample for one adult of a smaller species Western painted turtle. Painted turtles (e.g., mud, musk). Larger species (sliders, cooters) may need tanks 100 gallons and larger. -

Diptera: Tachinidae) Larvae

Welch: Competition by Ormia depleta 497 INTRASPECIFIC COMPETITION FOR RESOURCES BY ORMIA DEPLETA (DIPTERA: TACHINIDAE) LARVAE C. H. WELCH USDA/ARS/cmave, 1600 SW 23rd Drive, Gainesville, FL 32608 ABSTRACT Ormia depleta is a parasitoid of pest mole crickets in the southeastern United States. From 2 to 8 larvae of O. depleta were placed on each of 368 mole cricket hosts and allowed to de- velop. The weights of the host crickets, number of larvae placed, number of resulting pupae, and the weights of those pupae were all factored to determine optimal parasitoid density per host under laboratory rearing conditions. Based on larval survival and pupal weight, this study indicates that 4-5 larvae per host is optimal for laboratory rearing. Key Words: biocontrol, Scapteriscus, parasitoid, superparasitism RESUMEN Ormia depleta es un parasitoide de grillotopos en el sureste de los Estados Unidos. Entre 2 y 8 larvas de O. depleta se colocaron en 368 grillotopos huéspedes y se dejaron madurar. El peso de los huéspedes, el número de larvas de O. depleta colocadas, el número de pupas re- sultantes y el peso de las pupas fueron usados para determinar la densidad optima de para- sitoides en cada huésped para ser usadas en la reproducción de este parasitoide en el laboratorio. Nuestros resultados muestran que entre 4 y 5 larvas por cada grillotopo es la densidad optima para la reproducción en el laboratorio de este parasitoide. Translation provided by the author. Ormia depleta (Wiedemann) is a parasitoid of protocol requires hand inoculation of 3 planidia Scapteriscus spp. mole crickets, imported pests of under the posterior margin of the pronotum of turf and pasture grasses in the southeastern each host (R. -

AN INTRODUCTION to Texas Turtles

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE AN INTRODUCTION TO Texas Turtles Mark Klym An Introduction to Texas Turtles Turtle, tortoise or terrapin? Many people get confused by these terms, often using them interchangeably. Texas has a single species of tortoise, the Texas tortoise (Gopherus berlanderi) and a single species of terrapin, the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin). All of the remaining 28 species of the order Testudines found in Texas are called “turtles,” although some like the box turtles (Terrapene spp.) are highly terrestrial others are found only in marine (saltwater) settings. In some countries such as Great Britain or Australia, these terms are very specific and relate to the habit or habitat of the animal; in North America they are denoted using these definitions. Turtle: an aquatic or semi-aquatic animal with webbed feet. Tortoise: a terrestrial animal with clubbed feet, domed shell and generally inhabiting warmer regions. Whatever we call them, these animals are a unique tie to a period of earth’s history all but lost in the living world. Turtles are some of the oldest reptilian species on the earth, virtually unchanged in 200 million years or more! These slow-moving, tooth less, egg-laying creatures date back to the dinosaurs and still retain traits they used An Introduction to Texas Turtles | 1 to survive then. Although many turtles spend most of their lives in water, they are air-breathing animals and must come to the surface to breathe. If they spend all this time in water, why do we see them on logs, rocks and the shoreline so often? Unlike birds and mammals, turtles are ectothermic, or cold- blooded, meaning they rely on the temperature around them to regulate their body temperature. -

Background on Sea Turtles

Background on Sea Turtles Five of the seven species of sea turtles call Virginia waters home between the months of April and November. All five species are listed on the U.S. List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants and classified as either “Threatened” or “Endangered”. It is estimated that anywhere between five and ten thousand sea turtles enter the Chesapeake Bay during the spring and summer months. Of these the most common visitor is the loggerhead followed by the Kemp’s ridley, leatherback and green. The least common of the five species is the hawksbill. The Loggerhead is the largest hard-shelled sea turtle often reaching weights of 1000 lbs. However, the ones typically sighted in Virginia’s waters range in size from 50 to 300 lbs. The diet of the loggerhead is extensive including jellies, sponges, bivalves, gastropods, squid and shrimp. While visiting the Bay waters the loggerhead dines almost exclusively on horseshoe crabs. Virginia is the northern most nesting grounds for the loggerhead. Because the temperature of the nest dictates the sex of the turtle it is often thought that the few nests found in Virginia are producing predominately male offspring. Once the male turtles enter the water they will never return to land in their lifetime. Loggerheads are listed as a “Threatened” species. The Kemp’s ridley sea turtle is the second most frequent visitor in Virginia waters. It is the smallest of the species off Virginia’s coast reaching a maximum weight of just over 100 lbs. The specimens sited in Virginia are often less than 30 lbs. -

N.C. Turtles Checklist

Checklist of Turtles Historically Encountered In Coastal North Carolina by John Hairr, Keith Rittmaster and Ben Wunderly North Carolina Maritime Museums Compiled June 1, 2016 Suborder Family Common Name Scientific Name Conservation Status Testudines Cheloniidae loggerhead Caretta caretta Threatened green turtle Chelonia mydas Threatened hawksbill Eretmochelys imbricata Endangered Kemp’s ridley Lepidochelys kempii Endangered Dermochelyidae leatherback Dermochelys coriacea Endangered Chelydridae common snapping turtle Chelydra serpentina Emydidae eastern painted turtle Chrysemys picta spotted turtle Clemmys guttata eastern chicken turtle Deirochelys reticularia diamondback terrapin Malaclemys terrapin Special concern river cooter Pseudemys concinna redbelly turtle Pseudemys rubriventris eastern box turtle Terrapene carolina yellowbelly slider Trachemys scripta Kinosternidae striped mud turtle Kinosternon baurii eastern mud turtle Kinosternon subrubrum common musk turtle Sternotherus odoratus Trionychidae spiny softshell Apalone spinifera Special concern NOTE: This checklist was compiled and updated from several sources, both in the scientific and popular literature. For scientific names, we have relied on: Turtle Taxonomy Working Group [van Dijk, P.P., Iverson, J.B., Rhodin, A.G.J., Shaffer, H.B., and Bour, R.]. 2014. Turtles of the world, 7th edition: annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution with maps, and conservation status. In: Rhodin, A.G.J., Pritchard, P.C.H., van Dijk, P.P., Saumure, R.A., Buhlmann, K.A., Iverson, J.B., and Mittermeier, R.A. (Eds.). Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation Project of the IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group. Chelonian Research Monographs 5(7):000.329–479, doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v7.2014; The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. -

A Phylogenomic Analysis of Turtles ⇑ Nicholas G

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 83 (2015) 250–257 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A phylogenomic analysis of turtles ⇑ Nicholas G. Crawford a,b,1, James F. Parham c, ,1, Anna B. Sellas a, Brant C. Faircloth d, Travis C. Glenn e, Theodore J. Papenfuss f, James B. Henderson a, Madison H. Hansen a,g, W. Brian Simison a a Center for Comparative Genomics, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Drive, San Francisco, CA 94118, USA b Department of Genetics, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA c John D. Cooper Archaeological and Paleontological Center, Department of Geological Sciences, California State University, Fullerton, CA 92834, USA d Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA e Department of Environmental Health Science, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA f Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA g Mathematical and Computational Biology Department, Harvey Mudd College, 301 Platt Boulevard, Claremont, CA 9171, USA article info abstract Article history: Molecular analyses of turtle relationships have overturned prevailing morphological hypotheses and Received 11 July 2014 prompted the development of a new taxonomy. Here we provide the first genome-scale analysis of turtle Revised 16 October 2014 phylogeny. We sequenced 2381 ultraconserved element (UCE) loci representing a total of 1,718,154 bp of Accepted 28 October 2014 aligned sequence. Our sampling includes 32 turtle taxa representing all 14 recognized turtle families and Available online 4 November 2014 an additional six outgroups. Maximum likelihood, Bayesian, and species tree methods produce a single resolved phylogeny. -

The Common Snapping Turtle, Chelydra Serpentina

The Common Snapping Turtle, Chelydra serpentina Rylen Nakama FISH 423: Olden 12/5/14 Figure 1. The Common Snapping Turtle, one of the most widespread reptiles in North America. Photo taken in Quebec, Canada. Image from https://www.flickr.com/photos/yorthopia/7626614760/. Classification Order: Testudines Family: Chelydridae Genus: Chelydra Species: serpentina (Linnaeus, 1758) Previous research on Chelydra serpentina (Phillips et al., 1996) acknowledged four subspecies, C. s. serpentina (Northern U.S. and Figure 2. Side profile of Chelydra serpentina. Note Canada), C. s. osceola (Southeastern U.S.), C. s. the serrated posterior end of the carapace and the rossignonii (Central America), and C. s. tail’s raised central ridge. Photo from http://pelotes.jea.com/AnimalFact/Reptile/snapturt.ht acutirostris (South America). Recent IUCN m. reclassification of chelonians based on genetic analyses (Rhodin et al., 2010) elevated C. s. rossignonii and C. s. acutirostris to species level and established C. s. osceola as a synonym for C. s. serpentina, thus eliminating subspecies within C. serpentina. Antiquated distinctions between the two formerly recognized North American subspecies were based on negligible morphometric variations between the two populations. Interbreeding in the overlapping range of the two populations was well documented, further discrediting the validity of the subspecies distinction (Feuer, 1971; Aresco and Gunzburger, 2007). Therefore, any emphasis of subspecies differentiation in the ensuing literature should be disregarded. Figure 3. Front-view of a captured Chelydra Continued usage of invalid subspecies names is serpentina. Different skin textures and the distinctive pink mouth are visible from this angle. Photo from still prevalent in the exotic pet trade for C. -

A Case of Inversion and Duplication Involving Constitutive Heterochromatin

Genetics and Molecular Biology, 36, 3, 353-356 (2013) Copyright © 2013, Sociedade Brasileira de Genética. Printed in Brazil www.sbg.org.br Short Communication Cytogenetic comparison of Podocnemis expansa and Podocnemis unifilis: A case of inversion and duplication involving constitutive heterochromatin Ricardo José Gunski1, Isabel Souza Cunha2, Tiago Marafiga Degrandi1, Mario Ledesma3 and Analía Del Valle Garnero1 1Universidade Federal do Pampa, Campus São Gabriel, São Gabriel, RS, Brazil. 2Secretaria Municipal de Meio Ambiente e Turismo, São Desidério, BA, Brazil. 3Parque Ecológico “El Puma”, Candelaria, Argentina. Abstract Podocnemis expansa and P. unifilis present 2n = 28 chromosomes, a diploid number similar to those observed in other species of the genus. The aim of this study was to characterize these two species using conventional staining and differential CBG-, GTG and Ag-NOR banding. We analyzed specimens of P. expansa and P. unifilis from the state of Tocantins (Brazil), in which we found a 2n = 28 and karyotypes differing in the morphology of the 13th pair, which was submetacentric in P. expansa and telocentric in P. unifilis. The CBG-banding patterns revealed a heterochromatic block in the short arm of pair 13 of P. expansa and an interstitial one in pair 13 of P. unifilis, suggest- ing a pericentric inversion. Pair 14 of P. unifilis showed an insterstitial band in the long arm that was absent in P. expansa, suggesting a duplication in this region. Ag-NORs were observed in the first chromosome pair of both spe- cies and was associated to a secondary constriction and heterochromatic blocks. Keywords: chromosome banding, Ag-NORs, karyotype, chelonids. -

Turtles, All Marine Turtles, Have Been Documented Within the State’S Borders

Turtle Only four species of turtles, all marine turtles, have been documented within the state’s borders. Terrestrial and freshwater aquatic species of turtles do not occur in Alaska. Marine turtles are occasional visitors to Alaska’s Gulf Coast waters and are considered a natural part of the state’s marine ecosystem. Between 1960 and 2007 there were 19 reports of leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea), the world’s largest turtle. There have been 15 reports of Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas). The other two are extremely rare, there have been three reports of Olive ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) and two reports of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). Currently, all four species are listed as threatened or endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Prior to 1993, Alaska marine turtle sightings were mostly of live leatherback sea turtles; since then most observations have been of green sea turtle carcasses. At present, it is not possible to determine if this change is related to changes in oceanographic conditions, perhaps as the result of global warming, or to changes in the overall population size and distribution of these species. General description: Marine turtles are large, tropical/subtropical, thoroughly aquatic reptiles whose forelimbs or flippers are specially modified for swimming and are considerably larger than their hind limbs. Movements on land are awkward. Except for occasional basking by both sexes and egg-laying by females, turtles rarely come ashore. Turtles are among the longest-lived vertebrates. Although their age is often exaggerated, they probably live 50 to 100 years. Of the five recognized species of marine turtles, four (including the green sea turtle) belong to the family Cheloniidae. -

Harvested Testudines

Testudines HARVESTED – Is the species collected by humans? Species Common Name Harvested Cheloniidae sea turtles Caretta c. caretta Atlantic loggerhead Unk Chelonia m. mydas Atlantic green turtle YF Economically Chelonia mydas is the most important reptile in the world. Its flesh and its eggs serve as an important source of protein in many third-world nations where protein is scarce (Ernst et al. 1994) Eretmochelys i. imbricata Atlantic hawksbill YF hawksbill flesh and eggs are eaten in many parts of its range (Ernst et al. 1994); YC throughout its range it is hunted for the plates of its shells (Ernst et al. 1994) Lepidochelys kempii Kemp’s ridley or Atlantic ridley YF egg poaching caused the initial decline [in population size] (Delikat 1981; Hall et al. 1983; Lutz and Lutcavage 1989; Ross et al. 1989; Thompson 1989; National Research Council 1990; Caillouet et al. 1991) Dermochelyidae leatherback sea turtles Dermochelys c. coriacea Atlantic leatherback YF gathering the eggs for both commerce and personal consumption (Ernst et al. 1994) Chelydridae snapping turtles Chelydra s. serpentina eastern snapping turtle YF the flesh of the snapping turtle is tasty and eaten throughout the range…fresh eggs are edible if fried (Ernst et al. 1994) Emydidae pond turtles Chrysemys p. picta eastern painted turtle Unk Chrysemys p. marginata midland painted turtle Unk Clemmys guttata spotted turtle YP (Lovich and Jaworski 1988; Lovich 1989; J. Harding, pers. comm.) Clemmys insculpta wood turtle YP (Ernst et al. 1994) Clemmys muhlenbergii bog turtle YP (D.E. Collins 1990); YF eaten by people (Ernst et al. 1994) Deirochelys r.