Sitting Still

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 2 2015|2016 SEASON

2015|2016 SEASON Issue 2 TABLE OF Dear Friend, It has finally happened. It always CONTENTS seemed that Kiss Me, Kate was the perfect show for the Shakespeare 1 Title page Theatre Company to produce. It is Recipient of the 2012 Regional Theatre Tony Award® one of the wittiest musical comedies 3 Cast in the canon, featuring the finest Artistic Director Michael Kahn score Cole Porter ever wrote, Executive Director Chris Jennings 4 Director’s Word stuffed to the brim with songs romantic, hilarious, and sometimes both. It is also, not coincidentally, a landmark 8 Story, Musical Numbers adaptation of Shakespeare, a work that no less a critic than and Orchestra W.H. Auden considered greater than Shakespeare’s own The Taming of the Shrew. 9 Music Director’s Word All I can say to the multitudes who have suggested this show to me over the past 29 years is that we waited 13 About the Authors until the moment was right: until we knew we could do a production that could satisfy us, with a cast that could 14 The Taming of work wonders with this material. music and lyrics by Cole Porter the Screwball book by Samuel and Bella Spewack Also, of course, with the right director. He doesn’t need 18 It Takes Two any introduction, having directed two classic (and Performances begin November 17, 2015 classically influenced) musicals for us—2013–2014’s Opening Night November 23, 2015 (Times Two) award-winning staging of A Funny Thing Happened on the Sidney Harman Hall Way to the Forum and 2014–2015’s equally magnificent 24 Mapping the Play Man of La Mancha—but nonetheless I am very happy that STC Associate Artistic Director Alan Paul has agreed to Director Fight Director 26 Kiss Me, Kate and complete his trifecta with Kiss Me, Kate. -

Falsework Volume 4

SUMMER 2016, MAKING AMERICA AGAIN VOLUME 4: LISTEN IN, HEARING AND SPEAKING AMERICA 13 AUGUST 2016 this and additional materials available at www.hicrosa.org rom the perspective of an era dominated ostensibly by the visual This class, the fourth in Falsework School’s Making America media, radio appears as a lost medium, an archaic frequency at once Again series, explores radio and sound experiments as ways of Fmaterial and ideological whose political and cultural significance has investigating, producing, cultivating, and disrupting political declined dramatically since the end of World War II. Yet the antinomy of attachments. In which historical moments and under which radio and visual imagery may be less stable and more highly mediated conditions are different kinds of radio produced and different than a physiological model of sensibility would lead us to believe. The kinds of storytelling prioritized? What political impulses have influential conceptions of imagery developed by theorists such as Rudolf guided the making of interesting sound projects? Reading radio Arnheim, Ernst Gombrich, and Walter Benjamin have largely eclipsed the plays, essays, and interviews and listening to a variety of radio substantial speculative and even practical encounters sustained by these experiments, we will challenge each other to open our ears and authors with the medium of radio. Gombrich, for example, has published think more deeply about our listening experiences. We will end an essay on the mythological dimension of radio and, more specifically, on with recording clips of radio plays and our own sound his own wartime activities as a monitor of German broadcasts for the BBC experiments to be shared/broadcast. -

Carousel Horses from Private Couection

YOU CAN OWN A FINE REPRODUCTION OF A MULLER IN WOOD, BRONZE, OR ALUMINUM WOOD MULLER MILITARY HORSE wooden reproduction of Muller comes with a Certificate of (also available goat and rose horse $4,490) Authenticity and a Reproduction Serial Number $4,300 BRONZE GOAT (also available in military horse) $4,900 ALUMINUM ROSE HORSE (also available in military horse) PAINTED $1,300 ALUMINUM (optional, cost per horse basis) The Dimensions on the Horses are 5' high, 64" long 12" wide. OWN ONE OF THE FINE FIGURES SHOWN ABOVE OR SEND FOR INFORMATION ON OTHER FIGURES AVAILABLE. Majestic Manufacturing, Inc. P.O. Box 128, 4536 S.R. 7 • New Waterford, Ohio 44445 (216) 457.. 2447 or (216) 457.. 7280 • FAX (216) 457.. 7490 The Carousel News & Trader, September, 1993 3 LOOKING FOR SOMETHING NEW? Cafesjian sCarousel CREATE YOUR OWN CAROUSEL HORSE!! by Jennifer Raskob Kranz TRADIDONAL HORSE SOUiliWBSTERN HORSE Un1ln1shed Horse 19"x 27" ..... $ 34.95 + $7 s&h Brass Stand 50" high ............. $ 19.95 + $5 s&h Signed and numbered 500 limited edition prints Horse with Stand ................... $ 49.90 + $7 s&h of the 1914 MN State Fair Carousel. Flnished Horse w /Stand ........ $425.00 free shipping Print 24 x 24 $150" • plus 8" for shipping and handling. Horse is made In the USA JDADVE~ Send money order to: of a durable plastic 255 ROU'ffi 12 Jennifer Raskob Kranz. &JITE 1. •608:r:::lco=o-=E-=T:-:·939=l Order Now!! GROTON, CT06340 210 W. lOth St. • Hastin~ . MN 55033 Not Available in Stores! 612-437-2425 Phone: (800) 886-6055 Fax: (203) 546-1185 •20'16 dtJn.t~lni U1 rrJI4rlllitm ofurouul. -

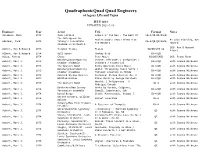

Quadraphonicquad Multichannel Engineers of All Surround Releases

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of all surround releases JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Type Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow MCH Dishwalla Services, State MCH Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Quad Abramson, Mark 1973 Judy Collins Colors of the Day - The Best Of CD-4/Q8/QR/SACD MCH Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD The Outrageous Dr. Stolen Goods: Gems Lifted from P: Alan Blaikley, Ken Quad Adelman, Jack 1972 Teleny's Incredible CD-4/Q8/QR/SACD the Masters Howard Plugged-In Orchestra MCH Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A MCH Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A MCH Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V MCH Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A MCH Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc MCH Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD MCH Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD QSS: Ron & Howard Quad Albert, Ron & Howard 1975 -

2017 DJ Music by Song

Artist Song 112 Cupid 112 Dance With Me Remix (Featuring Beanie Sigel) 112 Peaches & Cream 311 All Mixed Up 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Borders 311 Brodels 311 Color 311 The Continuous Life 311 Creature Feature 311 Dont Let Me Down 311 Don't Stay Home 311 Down 311 Electricity 311 Galaxy 311 Guns (Are For Pussies) 311 Hive 311 Inner Light Spectrum 311 Jackolantern's Weather 311 Jupiter 311 Light Years 311 Loco 311 Love Song 311 Misdirected Hostility 311 No Control 311 Prisoner 311 Purpose 311 Random 311 Rub A Dub 311 Running 311 Starshines 311 Stealing Happy Hours 311 Strangers 311 Sweet 311 T&P Combo 311 Transistor 311 Tune In 311 Use Of Time 311 What Was I Thinking 702 Where My Girls At 702 Where My Girls At? 2002 Lady of the Moon 2002 Summer's End !!! AM/FM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears .38 Special Hold On Loosely .38 Special Second Chance 'N Sync Bringin' Da Noise 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 'N Sync Crazy For You 'N Sync Digital Get Down 'N Sync Everything I Own 'N Sync For The Girl Who Has Everything 'N Sync Giddy Up 'N Sync Girlfriend 'N Sync God Must Have Spent A Little More Time On You 'N Sync Gone 'N Sync Here We Go 'N Sync Here We Go 'N Sync I Drive Myself Crazy 'N Sync I Just Wanna Be With You 'N Sync I Need Love 'N Sync I Thought She Knew 'N Sync I Want You Back 'N Sync I'll Be Good For You 'N Sync It Makes Me Ill 'N Sync It's Gonna Be Me 'N Sync It's Gonna Be Me 'N Sync Just Got Paid 'N Sync No Strings Attached 'N Sync Pop 'N Sync Sailing 'N Sync Tearin' Up My Heart 'N Sync That's When I'll Stop Loving You 'N Sync This I Promise You 'N Sync This I Promise You 'N Sync You Got It 'N Sync Feat. -

Song by ARTIST 2019

SONG LIST BY ARTIST - 2019 ARTIST SONG 112 Cupid 112 Dance With Me Remix (feat. Beanie Sigel) 112 Dance With Me Remix (Featuring Beanie Sigel) 112 Peaches & Cream 311 All Mixed Up 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Borders 311 Brodels 311 Color 311 The Continuous Life 311 Creature Feature 311 Dont Let Me Down 311 Don't Stay Home 311 Down 311 Electricity 311 Galaxy 311 Guns (Are For Pussies) 311 Hive 311 Inner Light Spectrum 311 Jackolantern's Weather 311 Jupiter 311 Light Years 311 Loco 311 Love Song 311 Misdirected Hostility 311 No Control 311 Prisoner 311 Purpose 311 Random 311 Rub A Dub 311 Running 311 Starshines 311 Stealing Happy Hours 311 Strangers 311 Sweet 311 T&P Combo 311 Transistor 311 Tune In 311 Use Of Time 311 What Was I Thinking 702 Where My Girls At 702 Where My Girls At? 2002 Lady of the Moon 2002 Summer's End !!! AM/FM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears ? and the Mysterians 96 Tears .38 Special Hold On Loosely .38 Special Second Chance 'Til Tuesday Voices Carry [미생 OST Part 3] 이승열 날아 (Fly) MV *NSYNC Tearin' Up My Heart (Radio Edit) #1 Party Band The Chicken Dance 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs Eden 10,000 Maniacs Few And Far Between 10,000 Maniacs Gold Rush Brides 10,000 Maniacs How You've Grown 10,000 Maniacs If You Intend 10,000 Maniacs I'm Not The Man 10,000 Maniacs Jezebel 10,000 Maniacs Stockton Gala Days 10,000 Maniacs These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc The Things We Do for Love 112 & The Notorious B.I.G. -

Quadraphonicquad Quad Engineers of Legacy Lps and Tapes

QuadraphonicQuad Quad Engineers of legacy LPs and Tapes JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes Abramson, Mark 1973 Judy Collins Colors of the Day - The Best Of CD-4/Q8/QR/SACD The Outrageous Dr. Stolen Goods: Gems Lifted from P: Alan Blaikley, Ken Adelman, Jack 1972 Teleny's Incredible CD-4/Q8/QR/SACD the Masters Howard Plugged-In Orchestra QSS: Ron & Howard Albert, Ron & Howard 1975 Stephen Stills Stills SQ/Q8/DTS CD Albert Albert, Ron & Howard 1974 Bill Wyman Monkey Grip CD-4/Q8 Allen, Murray 1974 Chase Pure Music SQ/Q8/SACD QSS: Frank Rand Weisberg/Contemporary Varese: Offrandes / Intégrales / Aubort, Marc J. 1973 CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Chamber Ensemble Octandre / Ecuatorial Aubort, Marc J. 1973 The Western Wind Early American Vocal Music CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Weisberg/Contemporary Weill: Threepenny Opera Suite / Aubort, Marc J. 1973 CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Chamber Ensemble Milhaud: Creation du Monde Aubort, Marc J. 1973 Concord String Quartet Rochberg: String Quartet No. 3 CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Aubort, Marc J. 1973 William Bolcom Piano Music by George Gershwin CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Vecchi: L'Amfiparnaso - A Aubort, Marc J. 1973 The Western Wind CD-4 with Joanna Nickrenz Madrigal Comedy DesRoches/New Jersey Works by Varese, Colgrass, Aubort, Marc J. 1974 CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Percussion Ensemble Cowell, Saperstein, Oak Aubort, Marc J. 1974 David Burge Crumb: Makrocosmos, Volume I CD-4/QR with Joanna Nickrenz Gerard Schwarz, William Aubort, Marc J. 1974 Cornet Favorites CD-4 with Joanna Nickrenz Bolcom Schwarz/New York Trumpet Aubort, Marc J. -

October 2020 | Tishrei-Heshvan 5781

The Award Winning » SAVOR SUKKOT (4-7) BUFFALO, ISRAEL & THE JEWISH WORLD | WWW.BUFFALOJEWISHFEDERATION.ORG OCTOBER 2020 | TISHREI-HESHVAN 5781 WELCOME: INSIDE: LOOK: NEW JCC BUFFALOVE HERD CEO (18) COMMUNITY (11) (24) THE MUSIC WILL PLAY FALL PERFORMANCE SCHEDULE FOR STREAMED CONCERT EVENTS FREE to all subscribers and available to patrons wishing to purchase a virtual ticket BPO Pops That Studio Sound: Jazz Classics for Lovers M&T BANK CLASSICS Sat Oct 17, 8pm Baroque Fireworks John Morris Russell, conductor Sat Dec 5, 8pm From the famed recording studios at Capitol JoAnn Falletta, conductor Records in Los Angeles, arranger Nelson Riddle Henry Ward, oboe and the biggest singing sensations of the era Caroline Gilbert, viola created a body of work that defines the cool Anna Shemetyeva, viola M&T BANK CLASSICS sophistication of popular jazz in the 1950s and Baroque is front and center as JoAnn A Celebration 60s. The BPO brings arrangements of classics by Falletta conducts Handel’s Music for the of the Seasons Gershwin, Porter, and Jobim, recorded by the RoyalFireworks with its iconic and lavish likes of Frank, Nat, and Ella, back to life in all their score, Bach’s randenburg Concerto No. 6, Sat Sep 26, 8pm original splendor with Buffalo crooners Katy Miner JoAnn Falletta, conductor and Marcello’s Oboe Concerto in C minor and Chris Vasquez. A romantic evening of sultry played by principal oboist Henry Ward, which Nikki Chooi, violin swing! echoes the lyricism of an aria. Your BPO Brass A theme of joyful rebirth takes center stage M&T BANK CLASSICS plays the exciting Canzon septimi toni No. -

List by Song Title

Song Title Artists 4 AM Goapele 73 Jennifer Hanson 1969 Keith Stegall 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 3121 Prince 6-8-12 Brian McKnight #1 *** Nelly #1 Dee Jay Goody Goody #1 Fun Frankie J (Anesthesia) - Pulling Teeth Metallica (Another Song) All Over Again Justin Timberlake (At) The End (Of The Rainbow) Earl Grant (Baby) Hully Gully Olympics (The) (Da Le) Taleo Santana (Da Le) Yaleo Santana (Do The) Push And Pull, Part 1 Rufus Thomas (Don't Fear) The Reaper Blue Oyster Cult (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again L.T.D. (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 Nat King Cole (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash (Goin') Wild For You Baby Bonnie Raitt (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody WrongB.J. Thomas Song (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Otis Redding (I Don't Know Why) But I Do Clarence "Frogman" Henry (I Got) A Good 'Un John Lee Hooker (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace (I Just Want It) To Be Over Keyshia Cole (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (The) (I Know) I'm Losing You Temptations (The) (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons ** Sam Cooke (If Only Life Could Be Like) Hollywood Killian Wells (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! ** Shania Twain (I'm A) Stand By My Woman Man Ronnie Milsap (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkeys (The) (I'm Settin') Fancy Free Oak Ridge Boys (The) (It Must Have Been Ol') Santa Claus Harry Connick, Jr. -

Marianne Stevens

The December 2012 Vol. 28, No. 12 Carousel $6.95 News & Trader Marianne Stevens Carousel News & Trader, December 2012 www.carouselnews.com 1929 - 2012 1 FANTASTIC FIbERgLASS FIgURES VERY LImITEd qUANTITIES ThE MoldS ARE LITERALLY bROkEN on ThESE FIbERgLASS FIgURES FROm ThE bUd hURLbUT Knotts bERRY FARm Collection See more photos and prices at www.antiquecarousels.com or call CONTCONTAACTCT:: TM 11001 PEORIA STREET • SUN VALLEY, CA 91352 Brass Ring 818-394-0028 • fax: 818-332-0062 Entertainment email: [email protected] • www.carousel.com ALL THINGS CAROUSEL FOR OVER 35 YEARS Visit us at IAAPA in Booth #4026 historic Carousels FOR SALE 1925 PTC. Last operated kiddieland in melrose, IL 3-row carousel with an amazing 16 signature PTC horses. JUST IN - 1890 Looff Carousel. The famous “broadway Flying horses” from Coney Island. Just undergone museum restoration. Three extremely rare dogs among the menagerie. 1927 Illions Supreme – SOLd This is the last of the three complete supremes including the world famous American beauty rose horse. 1900s PTC Carousel Last operated by the world famous Strates shows. In storage awaiting restoration. 1880s herschell-Spillman Steam-Operated Carousel Original steam engine with 24 animals and 2 chariots. 1900s PTC Carousel Rare 4-row unrestored carousel great for community project. Priced to sell. Restoration available. 1920s dentzel Carousel Another huge 4-row machine, just like disneyland’s Carousel, with 78 replacement animals. 1900s Looff menagerie Carousel huge 4-row menagerie carousel. has been in storage for years, awaiting restoration. 1900s dentzel menagerie Carousel All original animals. Currently up and operating looking for new home. -

JB DB by Artist

Song Title …. Artists Drop (Dirty) …. 216 Hey Hey …. 216 Baby Come On …. (+44) When Your Heart Stops Beating …. (+44) 96 Tears …. ? & The Mysterians Rubber Bullets …. 10cc The Things We Do For Love …. 10cc The Things We Do For Love …. 10cc Come See Me …. 112' Cupid …. 112' Damn …. 112' Dance With Me …. 112' God Knows …. 112' I'm Sorry (Interlude) …. 112' Intro …. 112' Just A Little While …. 112' Just A Little While …. 112' Last To Know …. 112' Let This Go …. 112' Let This Go …. 112' Love Me …. 112' My Mistakes …. 112' Nowhere …. 112' Only You …. 112' Peaches & Cream …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Clean) …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Dirty) …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Inst) …. 112' That's How Close We Are …. 112' U Already Know …. 112' U Already Know …. 112' We Goin' Be Alright …. 112' What If …. 112' What The H**l Do You Want …. 112' Why Can't We Get Along …. 112' You Already Know (Clean) …. 112' Dance Wit Me (Remix) …. 112' (w Beanie Segal) It's Over (Remix) …. 112' (w G.Dep & Prodigy) The Way …. 112' (w Jermaine Dupri) Hot & Wet (Dirty) …. 112' (w Ludacris) Love Me …. 112' (w Mase) Only You …. 112' (w Notorious B.I.G.) Anywhere (Remix) …. 112' (w Shyne) If I Can Hit …. 112' (w T.I.) If I Hit …. 112' (w T.I.) Closing The Club …. 112' (w Three 6 Mafia) Dunkie Butt …. 12 Gauge Lie To Me …. 12 Stones 1, 2, 3 Red Light …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Goody Goody Gumdrops …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Indian Giver …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simple Simon Says …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simple Simon Says …. -

The Gift Horse, Inc. Amount Item __

For Sale 36'0" Chance-Dentzel style 3-abreast carousel, this unit is 1990 Chance Carousel complete and fully operational. The carousel has all the options: *Full scenery package, ceiling center top and bottom complete with mirrors. Rounding boards have beveled edge mirrors. *The carousel scenery is done in red and antique white and gold. The structure is red and the tent top is red and yellow with tent pole sleeve. *The floor is finished oak, all trim is brass. *The outside row of horses are Bradley and Kay horses. *The unit comes complete with custom ticket/operators booth, auto ticket dispenser, custom railing system and complete sound system containing: The unit is in operations and can be seen by appointment. Tascom CD-CD player (studio quality); 600 with Peavy Declass amp.; 6 electro The unit is very fancy and highly detailed. voice MS802 speakers; CD players and For more information contact Jerry Kroos at 614·258·2940 amp mounted in security rack PATTERNS FOR CAROUSEL HORSES Each Series has 25 pages ofline drawings. About 20 are assorted horses- standers and jumpers of different types from different carvers and companies. Four are mena.gerie animals and one horse head. SERIES 1 Apr 90 SERIES 8 July 91 2 July 90 9 Sept 91 3 Sept 90 10 Nov91 4 Nov90 11 Jan92 5 Jan 91 12 Apr92 6 Mar 91 13 July 92 7 May 91 14 Oct92 See carving pattern on page 44 MENAGERIE FROM 1-6 Mar91 MENAGERIE FROM 7 -12 Feb 92 K.B. LEATHER ART KATHLEEN BOND 2341 Irwin Each set is $12.93 plus $2.00 P&:H.