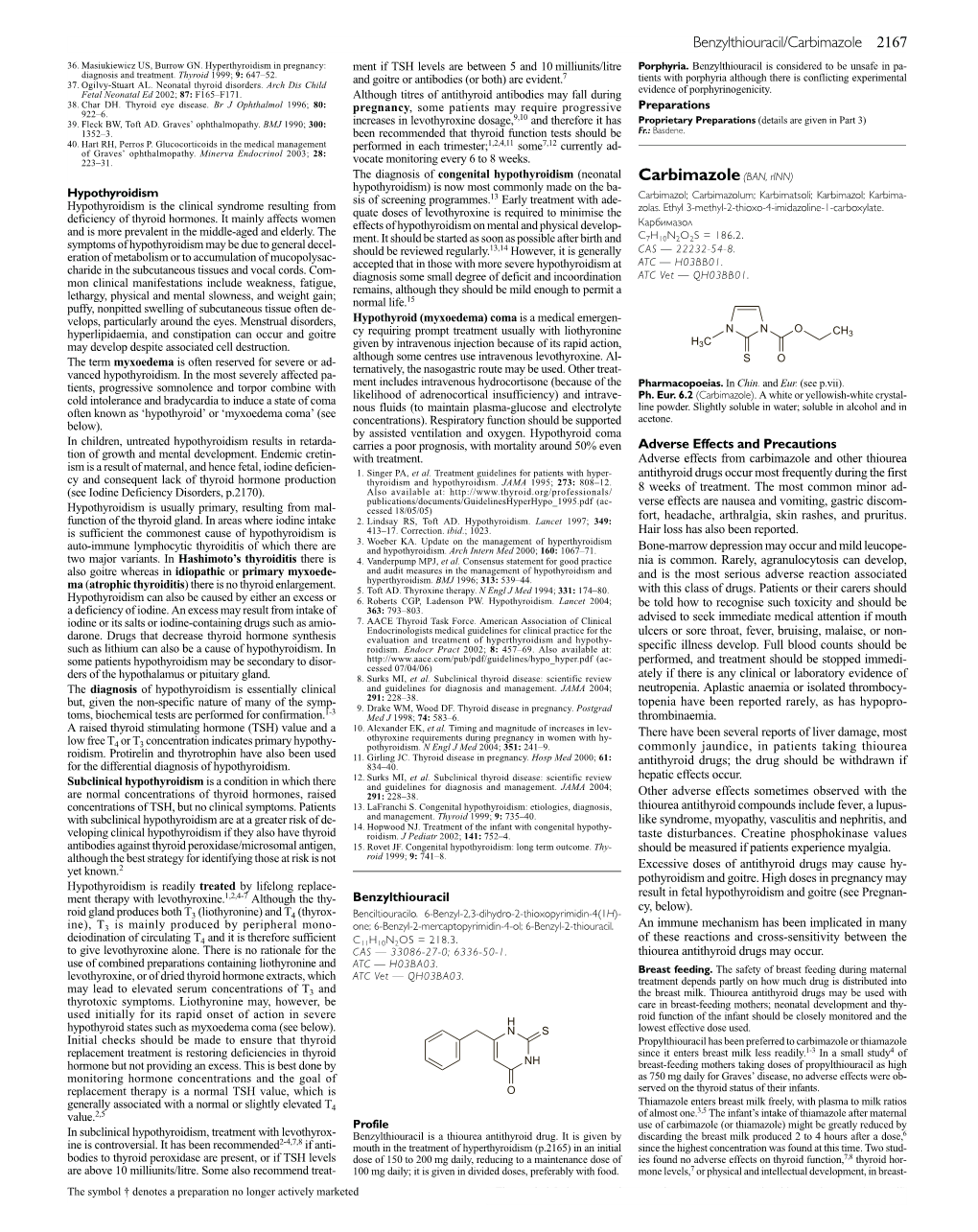

Carbimazole(BAN, Rinn)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Induction of Proteolysis in Purulent Sputum by Iodides * JACK LIEBERMAN and NATHANIEL B

Journal of Clinical Investigalton Vol. 43, No. 10, 1964 The Induction of Proteolysis in Purulent Sputum by Iodides * JACK LIEBERMAN AND NATHANIEL B. KURNICK (From the Veterans Administration Hospital, Long Beach, and the Department of Medicine, the University of California Center for Medical Sciences at Los Angeles, Calif.) Iodide, in the form of potassium or sodium io- have even greater proteolysis-inducing activities dide, is widely used as an expectorant for patients than inorganic iodide. with viscid sputum. The iodides are thought to act by increasing the volume of aqueous secretions Methods from bronchial glands (1). This mechanism for Source of sputum specimens. Purulent sputa were ob- the effect of iodides probably plays an important tained from 17 patients with cystic fibrosis and from 22 role, but an additional mechanism whereby iodides with other types of pulmonary problems (Table VIII). may act to thin viscid respiratory secretions was Two specimens of pus were obtained and studied in a demonstrated during a study of the proteolytic similar fashion. The sputa were collected in glass jars kept in the patients' home freezers at approximately enzyme systems of purulent sputum. - 100 C over a 2- to 5-day period and then were kept Purulent sputum contains a number of proteo- frozen at - 200 C up to 3 weeks. Sputa collected from lytic enzymes, probably derived from leukocytes hospitalized patients were frozen after a 4-hour collection (2-4). These proteases, however, are ineffective period. in causing hydrolysis of the native protein in puru- Preparation of sputum homogenates. Individual spu- tum specimens were homogenized in distilled water with lent sputum and do not appear to contribute sig- a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer to form 10% (wet nificantly to the spontaneous liquefaction of these weight to volume) homogenates. -

The Chemistry of Marine Sponges∗ 4 Sherif S

The Chemistry of Marine Sponges∗ 4 Sherif S. Ebada and Peter Proksch Contents 4.1 Introduction ................................................................................ 192 4.2 Alkaloids .................................................................................. 193 4.2.1 Manzamine Alkaloids ............................................................. 193 4.2.2 Bromopyrrole Alkaloids .......................................................... 196 4.2.3 Bromotyrosine Derivatives ....................................................... 208 4.3 Peptides .................................................................................... 217 4.4 Terpenes ................................................................................... 240 4.4.1 Sesterterpenes (C25)............................................................... 241 4.4.2 Triterpenes (C30).................................................................. 250 4.5 Concluding Remarks ...................................................................... 268 4.6 Study Questions ........................................................................... 269 References ....................................................................................... 270 Abstract Marine sponges continue to attract wide attention from marine natural product chemists and pharmacologists alike due to their remarkable diversity of bioac- tive compounds. Since the early days of marine natural products research in ∗The section on sponge-derived “terpenes” is from a review article published -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

WO 2018/064098 A1 05 April 2018 (05.04.2018) WI P Ο I PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll^ International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2018/064098 A1 05 April 2018 (05.04.2018) WI P Ο I PCT (51) International Patent Classification: Published: C07K14/47 (2006.01) C07K16/18 (2006.01) — with international search report (Art. 21(3)) A 61K 38/17 (2006.01) — before the expiration of the time limit for amending the (21) International Application Number: claims and to be republished in the event of receipt of PCT/US2017/053597 amendments (Rule 48.2(h)) — with sequence listing part of description (Rule 5.2(a)) (22) International Filing Date: 27 September 2017 (27.09.2017) (25) Filing Language: English (26) Publication Language: English (30) Priority Data: 62/401,123 28 September 2016 (28.09.2016) US (71) Applicant: COHBAR, INC. [US/US]; 1455 Adams Drive, Menlo Park, CA 94025 (US). (72) Inventors: CUNDY, Kenneth, C.; c/o Cohbar, Inc., 1455 Adams Drive, Menlo Park, CA 94025 (US). GRINDSTAFF, Kent, K.; c/o Cohbar, Inc., 1455 Adams ____ Drive, Menlo Park, CA 94025 (US). MAGNAN, Remi; c/ o Cohbar, Inc., 1455 Adams Drive, Menlo Park, CA 94025 (US). LUO, Wendy; c/o Cohbar, Inc., 1455 Adams Dri ve, Menlo Park, CA 94025 (US). YAO, Yongjin; c/o Co — hbar, Inc., 1455 Adams Drive, Menlo Park, CA 94025 (US). — YAN, Liang, Zeng; c/o Cohbar, Inc., 1455 Adams Drive, Menlo Park, CA 94025 (US). (74) Agent: GASS, David, A. et al.; Marshall, Gerstein & Borun LLP, 233 S. -

Alphabetical Listing of ATC Drugs & Codes

Alphabetical Listing of ATC drugs & codes. Introduction This file is an alphabetical listing of ATC codes as supplied to us in November 1999. It is supplied free as a service to those who care about good medicine use by mSupply support. To get an overview of the ATC system, use the “ATC categories.pdf” document also alvailable from www.msupply.org.nz Thanks to the WHO collaborating centre for Drug Statistics & Methodology, Norway, for supplying the raw data. I have intentionally supplied these files as PDFs so that they are not quite so easily manipulated and redistributed. I am told there is no copyright on the files, but it still seems polite to ask before using other people’s work, so please contact <[email protected]> for permission before asking us for text files. mSupply support also distributes mSupply software for inventory control, which has an inbuilt system for reporting on medicine usage using the ATC system You can download a full working version from www.msupply.org.nz Craig Drown, mSupply Support <[email protected]> April 2000 A (2-benzhydryloxyethyl)diethyl-methylammonium iodide A03AB16 0.3 g O 2-(4-chlorphenoxy)-ethanol D01AE06 4-dimethylaminophenol V03AB27 Abciximab B01AC13 25 mg P Absorbable gelatin sponge B02BC01 Acadesine C01EB13 Acamprosate V03AA03 2 g O Acarbose A10BF01 0.3 g O Acebutolol C07AB04 0.4 g O,P Acebutolol and thiazides C07BB04 Aceclidine S01EB08 Aceclidine, combinations S01EB58 Aceclofenac M01AB16 0.2 g O Acefylline piperazine R03DA09 Acemetacin M01AB11 Acenocoumarol B01AA07 5 mg O Acepromazine N05AA04 -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan the UNIVERSITY of OKLAHOMA

Thia dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received Mic 61-1128 JENKmS, Marie Magdalen. A STUDY OF THE EFFECT OF GOITROGENS AND THYROID COMPOUNDS ON RESPIRATION RATES IN PCANARIANS. The U niversity of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1961 Zoology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE A STUDY OF THE EFFECT OF GOITROGENS AND THYROID COMPOUNDS ON RESPIRATION RATES IN PLANARIANS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY MARIE MAGDALEN JENKINS Norman, Oklahoma I960 A STUDY OF THE EFFECT OF GOITROGENS AND THYROID COMPOUNDS ON RESPIRATION RATES IN PLANARIANS APPROVED BY DISSERTATION COMMITTEE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This investigation was carried out during the author’s tenure as the recipient of a grant from the Southern Fellowship Fund, 1959-60* The work was also supported in part by grants from the National Science Foundation (G-3209) and the University of Oklahoma Alumni Development Fund. The author wishes to express her appreciation for the assistance thus provided. Sincere appreciation is also extended to Dr, Harriet Harvey, major professor, for her assistance in carrying out the investigation and in the preparation of the manuscript; to Dr. Harley P. Brown, for his aid in obtaining and culturing the planariana; and to Dr* Alfred F. Naylor, for his direction in carrying out the statistical analyses. The author also wishes to thank the following; Dr. J, T, Self and Dr. Carl D, Riggs, who assisted in obtaining materials and equipment for the preliminary work at the University of Oklahoma Biological Station; Oscar Lowrance, owner of Buckhom Springs property, who gave permission to collect the planarians; Calvin Beames, who assisted in the solution of several technical problems; and the many faculty members and graduate students in zoology and plant sciences who contributed to the investiga tion. -

Comparative Kinetic Characterization of Rat Thyroid Iodotyrosine Dehalogenase and Iodothyronine Deiodinase Type 1

385 Comparative kinetic characterization of rat thyroid iodotyrosine dehalogenase and iodothyronine deiodinase type 1 J C Solís-S, P Villalobos, A Orozco and C Valverde-R Department of Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, Institute of Neurobiology, UNAM, Campus UNAM-UAQ Juriquilla, Queretaro, Qro 76230, Mexico (Requests for offprints should be addressed to J C Solís-S; Email: [email protected]) Abstract The initial characterization of a thyroid iodotyrosine of the two different dehalogenating enzymes has not yet dehalogenase (tDh), which deiodinates mono-iodotyrosine been clearly defined. This work compares and contrasts and di-iodotyrosine, was made almost 50 years ago, but the kinetic properties of tDh and ID1 in the rat thyroid little is known about its catalytic and kinetic properties. gland. Differential affinities for substrates, cofactors and A distinct group of dehalogenases, the so-called iodo- inhibitors distinguish the two activities, and a reaction thyronine deiodinases (IDs), that specifically remove mechanism for tDh is proposed. The results reported here iodine atoms from iodothyronines were subsequently support the view that the rat thyroid gland has a distinctive discovered and have been extensively characterized. set of dehalogenases specialized in iodine metabolism. Iodothyronine deiodinase type 1 (ID1) is highly expressed Journal of Endocrinology (2004) 181, 385–392 in the rat thyroid gland, but the co-expression in this tissue Introduction inactive intracellular THs in practically all vertebrate tissues (Köhrle 2000, Bianco et al. 2002). There seems to Iodine, the rate-limiting trace element in the biosynthesis be important species-specific differences regarding the of iodothyronines or thyroid hormones (THs), is actively expression of IDs in the thyroid gland. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,821,928 B2 Hemmingsen Et Al

US008821928B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,821,928 B2 Hemmingsen et al. (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 2, 2014 (54) CONTROLLED RELEASE 5,869,097 A 2/1999 Wong et al. PHARMACEUTICAL COMPOSITIONS FOR 6,103,261 A 8, 2000 Chasin et al. 2003.01.18641 A1 6/2003 Maloney et al. PROLONGED EFFECT 2003/O133976 A1* 7/2003 Pather et al. .................. 424/466 2004/O151772 A1 8/2004 Andersen et al. (75) Inventors: Pernille Hoyrup Hemmingsen, 2005.0053655 A1 3/2005 Yang et al. Bagsvaerd (DK); Anders Vagno 2005/O158382 A1* 7/2005 Cruz et al. .................... 424/468 2006, O1939 12 A1 8, 2006 KetSela et al. Pedersen, Virum (DK); Daniel 2007/OOO3617 A1 1/2007 Fischer et al. Bar-Shalom, Kokkedal (DK) 2007,0004797 A1 1/2007 Weyers et al. (73) Assignee: Egalet Ltd., London (GB) 2007. O190142 A1 8, 2007 Breitenbach et al. (Continued) (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this patent is extended or adjusted under 35 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS U.S.C. 154(b) by 1052 days. DE 202006O14131 1, 2007 EP O435,726 8, 1991 (21) Appl. No.: 12/602.953 (Continued) (22) PCT Filed: Jun. 4, 2008 OTHER PUBLICATIONS (86). PCT No.: PCT/EP2008/056910 Krogel etal (Pharmaceutical Research, vol. 15, 1998, pp. 474-481).* Notification of Transmittal of the International Search Report and the S371 (c)(1), Written Opinion of the International Searching Authority issued Jul. (2), (4) Date: Jun. 7, 2010 8, 2008 in International Application No. PCT/DK2008/000016. International Preliminary Reporton Patentability issued Jul. -

Pierangelo Metrangolo Giuseppe Resnati Editors Impact on Materials

Topics in Current Chemistry 358 Pierangelo Metrangolo Giuseppe Resnati Editors Halogen Bonding I Impact on Materials Chemistry and Life Sciences 358 Topics in Current Chemistry Editorial Board: H. Bayley, Oxford, UK K.N. Houk, Los Angeles, CA, USA G. Hughes, CA, USA C.A. Hunter, Sheffield, UK K. Ishihara, Chikusa, Japan M.J. Krische, Austin, TX, USA J.-M. Lehn, Strasbourg Cedex, France R. Luque, Cordoba, Spain M. Olivucci, Siena, Italy J.S. Siegel, Nankai District, China J. Thiem, Hamburg, Germany M. Venturi, Bologna, Italy C.-H. Wong, Taipei, Taiwan H.N.C. Wong, Shatin, Hong Kong [email protected] Aims and Scope The series Topics in Current Chemistry presents critical reviews of the present and future trends in modern chemical research. The scope of coverage includes all areas of chemical science including the interfaces with related disciplines such as biology, medicine and materials science. The goal of each thematic volume is to give the non-specialist reader, whether at the university or in industry, a comprehensive overview of an area where new insights are emerging that are of interest to larger scientific audience. Thus each review within the volume critically surveys one aspect of that topic and places it within the context of the volume as a whole. The most significant developments of the last 5 to 10 years should be presented. A description of the laboratory procedures involved is often useful to the reader. The coverage should not be exhaustive in data, but should rather be conceptual, concentrating on the methodological thinking that will allow the non-specialist reader to understand the information presented. -

Diccionario Del Sistema De Clasificación Anatómica, Terapéutica, Química - ATC CATALOGO SECTORIAL DE PRODUCTOS FARMACEUTICOS

DIRECCION GENERAL DE MEDICAMENTOS, INSUMOS Y DROGAS - DIGEMID EQUIPO DE ASESORIA - AREA DE CATALOGACION Diccionario del Sistema de Clasificación Anatómica, Terapéutica, Química - ATC CATALOGO SECTORIAL DE PRODUCTOS FARMACEUTICOS CODIGO DESCRIPCION ATC EN CASTELLANO DESCRIPCION ATC EN INGLES FUENTE A TRACTO ALIMENTARIO Y METABOLISMO ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM ATC OMS A01 PREPARADOS ESTOMATOLÓGICOS STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS ATC OMS A01A PREPARADOS ESTOMATOLÓGICOS STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS ATC OMS A01AA Agentes para la profilaxis de las caries Caries prophylactic agents ATC OMS A01AA01 Fluoruro de sodio Sodium fluoride ATC OMS A01AA02 Monofluorfosfato de sodio Sodium monofluorophosphate ATC OMS A01AA03 Olaflur Olaflur ATC OMS A01AA04 Fluoruro de estaño Stannous fluoride ATC OMS A01AA30 Combinaciones Combinations ATC OMS A01AA51 Fluoruro de sodio, combinaciones Sodium fluoride, combinations ATC OMS A01AB Antiinfecciosos y antisépticos para el tratamiento oral local Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment ATC OMS A01AB02 Peróxido de hidrógeno Hydrogen peroxide ATC OMS A01AB03 Clorhexidina Chlorhexidine ATC OMS A01AB04 Amfotericina B Amphotericin B ATC OMS A01AB05 Polinoxilina Polynoxylin ATC OMS A01AB06 Domifeno Domiphen ATC OMS A01AB07 Oxiquinolina Oxyquinoline ATC OMS A01AB08 Neomicina Neomycin ATC OMS A01AB09 Miconazol Miconazole ATC OMS A01AB10 Natamicina Natamycin ATC OMS A01AB11 Varios Various ATC OMS A01AB12 Hexetidina Hexetidine ATC OMS A01AB13 Tetraciclina Tetracycline ATC OMS A01AB14 Cloruro de benzoxonio -

Benzylthiouracil-Induced ANCA-Associated Vasculitis: a Case Report and Literature Review

European Journal of Case Reports in Internal Medicine Benzylthiouracil-induced ANCA-associated Vasculitis: A Case Report and Literature Review Fatima Bensiradj1, Mathilde Hignard2, Rand Nakkash1, Alice Proux1, Nathalie Massy3, Nadir Kadri1, Jean Doucet1, Isabelle Landrin1 1Fédération de Médecine Gériatrie Thérapeutique, Rouen, France 2Département de Pharmacie, CHU de Rouen, Rouen, France 3Centre Régional de Pharmacovigilance, Rouen, France Doi: 10.12890/2019_001283 - European Journal of Case Reports in Internal Medicine - © EFIM 2019 Received: 20/09/2019 Accepted: 23/09/2019 Published: 10/12/2019 How to cite this article: Bensiradj F, Hignard M, Nakkash R, Proux A, Massy N, Kadri N, Doucet J, Landrin I. Benzylthiouracil-induced ANCA-associated vasculitis: a case report and literature review. EJCRIM 2019;6: doi:10.12890/2019_001283. Conflicts of Interests: The Authors declare that there are no competing interest This article is licensed under a Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 License ABSTRACT Iatrogenic antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) is not exceptional. Many cases of small vessel vasculitis induced by anti-thyroid drugs (ATD), mainly propylthiouracil (PTU), have been reported. We present a case of AAV related to another ATD: benzylthiouracil (BTU) and review the literature. An 84-year-old man with a 4-year history of multinodular goitre with hyperthyroidism was treated with BTU. He presented an acute syndrome with weakness, fever, epigastric pain and abdominal distension. Lactate and lipase tests were normal. An abdominal scan showed a thrombosis of the splenic artery with splenic infarction. We excluded a hypothesis of associated embolic aetiology: atrial fibrillation, atrial myxoma, intraventricular thrombus or artery aneurysm. -

Metabolism of 3-Iodotyrosine and 3,5-Diiodotyrosine by Thyroid Extracts

Scholars' Mine Masters Theses Student Theses and Dissertations 1970 Metabolism of 3-iodotyrosine and 3,5-diiodotyrosine by thyroid extracts Shih-ying Sun Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses Part of the Chemistry Commons Department: Recommended Citation Sun, Shih-ying, "Metabolism of 3-iodotyrosine and 3,5-diiodotyrosine by thyroid extracts" (1970). Masters Theses. 7056. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses/7056 This thesis is brought to you by Scholars' Mine, a service of the Missouri S&T Library and Learning Resources. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. METABOLISM OF 3-IODOTYROSINE AND 3, 5-DIIODOTYROSINE BY THYROID EXTRACTS ..... ! ' BY SHm-YING SUN, 1943- A THESIS submitted to the faculty of UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI - ROLLA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN CHEMISTRY Rolla, Missouri 1970 T2328 c. I 73 pages Approved by i)n neiL (advisor) ~ .~et__ cf3v.~ /¢?£;;~ 183322 ii ABSTRACT A porcine thyroid enzyme was extracted from thyroid tissue by homo genization and differentia.! centrifugation. The enzyme was capable of metabol izing both 3-iodotyrosine and 3, 5-diiodotyrosine. All of the thyroid subcellular particles produced a fluorescent compound when incubated with these substrates. When the 1, 000 x g sediment was supplemented with the 48,000 x g supernatant a. second compound was formed. The compound was UV absorbing and has been identified as either 3-iodo-4-hydroxybenza.ldehyde or 3, 5-diiodo-4-hydroxy benzaldehyde depending upon which substrate was used.