KCPR: Changes Through the Generations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EMWIN Text Product Catalog

NWS EMWIN Text Product Catalog (rev 210525) This document addresses the identification of text products appearing on the US National Weather Service (NWS) Emergency Managers Weather Information Network (EMWIN) service. Information on the image products on the EMWIN service is published here: https://www.weather.gov/media/emwin/EMWIN_Image_and_Text_Data_Capture_Catalog_v1.3d.pdf The information in this document identifies the data used by the NWS in the operation of the EMWIN dissemination service. The EMWIN service is available to the public on the NESDIS HRIT/EMWIN satellite broadcast from the GOES-East (GOES-16) and GOES-West (GOES-17) satellites, and on the NWS EMWIN FTP file service. Further information is available on the Documents tab of the NWS EMWIN web page: https://www.weather.gov/emwin/ Text products on the EMWIN service may be separated into two groups: International Products. International products – those received from countries outside the United States (US), its possessions and territories – are formatted to WMO standards per WMO Pub 386. Appendix A - AWDS Table, provides an explicit list of International text products by WMO header. Note - The US National Weather Service does release a smaller set of products grouped with the International Products by virtue of the absence of an AWIPS ID on the line immediately following the WMO header (see “US National Products” below). US National Products. US National products are formatted to WMO standards per WMO Pub 386, but include an AWIPS ID field on the line immediately following the WMO header. This field is six bytes in length consisting of four to six left-justified alpha-numeric characters and spaces to fill to the six byte field length where necessary. -

Outpost, November 4, 1975

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@CalPoly page one Take a by Steven Seybold photos by Tony Hertz K„ flying contains ■ message for all who wish to rauntta thamsalvas with tha simpla, dalightful pleasures of life. Thara ara many who spand fortunes and years trying to regain tha simpla joys known so wall in childhood. Psycho-therapy, transactional analysis. Qastalt therapy, sanaitivity sessions, meditation, and many more techniques ara experimented by thousande desperately trying to break through a calloused maturity to thoaa vibrant joys of a playful child. Dinosh Bahadur, a master kite man . r from India, recognized tha need for - westerners to return to the natural aaay _______ Ik— pleasures of kite flying, Hla store In 8an Francisco, “Coma Fly a Kite, has bean a maces of information and inspiration. Ha has provided many helpful hints to those interested in kiting, but more than that, ho has inspired others to follow his path happiness One such inspired man Is Dave Whitver. A former art teacher. Whltver is now a disciple of the yoga of kiting. Shades of gray streaked through his wavy brown hair and ware it not for hia natural smile and soft easy laughter, I would have thought him an aging man. Whltver die* cussed his new art and what it means to him. “I hod to find a way out of the slientated society which was alienating me from happiness. My way ia kiting," ho said. Whltver, who now manages his own kite shop "Allied Arts" In Baywood Park, says, "Kiting is mors than a child's gams or idle hobby. -

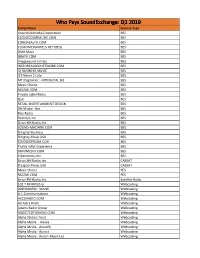

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

Federal Communications Commission DA 05-2005 Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission DA 05-2005 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Amendment of Section 73.202(b) ) MB Docket No. 05-88 Table of Allotments, ) RM-11173 FM Broadcast Stations. ) RM-11177 (San Luis Obispo and Lost Hills, California and ) Maricopa, California) REPORT AND ORDER (Proceeding Terminated) Adopted: July 13, 2005 Released: July 15, 2005 By the Assistant Chief, Audio Division, Media Bureau: 1. The Audio Division considers herein the Notice of Proposed Rule Making (“Notice”),1 which requested comments on two mutually exclusive proposals. The first proposal, filed by GTM San Luis Obispo (“GTM San Luis”), licensee of Station KLRM(FM), San Luis Obispo, California, proposing the substitution of Channel 245B1 for Channel 246B1 at San Luis Obispo, California, reallotment of Channel 245B1 from San Luis Obispo to Lost Hills, California, as its second local service, and modification of the Station KLRM(FM) license accordingly. The second proposal, filed by 105 Mountain Air, Inc. (“Mountain Air”) requesting the allotment of Channel 245A at Maricopa, California, as its second local service. GTM San Luis filed comments and Motion to Dismiss.2 There were no counterproposals or additional comments received in response to this proceeding. 2. Background. As stated in the Notice, each petitioner was requested to demonstrate in its comments why their respective community should receive the requested allotment given that both proposals cannot be accommodated in compliance with the minimum distance separation requirements of Section 73.207(b) of the Commission’s Rules. The proposals are located 52.4 kilometers apart whereas the minimum distance separation requirement is 143 kilometers. -

DRAFT Communications and Engagement Plan (Part of Chapter 11) Paso Robles Subbasin Groundwater Sustainability Plan

DRAFT Communications and Engagement Plan (part of Chapter 11) Paso Robles Subbasin Groundwater Sustainability Plan Published on: July 18, 2018 Received by the Paso Basin Cooperative Committee: July 25, 2018 Posted on PasoGCP.com: August 31, 2018 Close of 45‐day public comment period: October 15, 2018 This Draft document is posted on pasogcp.com and is being distributed to the five Paso Robles Subbasin Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs) to receive and file. Comments from the public are being collected using a comment form. The form can be found online at pasogcp.com. If you require a paper form to submit by postal mail, contact your local GSA. County of San Luis Obispo Shandon‐San Juan Water District Heritage Ranch CSD San Miguel CSD City of Paso Robles DRAFT COMMUNICATION & ENGAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE PASO ROBLES SUBBASIN GROUNDWATER SUSTAINABILITY PLAN JULY 2018 Paso Robles Subbasin Groundwater Sustainability Agencies ― County of San Luis Obispo ― City of Paso Robles ― San Miguel Community Services District ― Heritage Ranch Community Services District ― Shandon San Juan Water District DRAFT Page Left Blank Intentionally Communication & Engagement Plan for the Paso Robles Subbasin GSP 2 | Page DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 2 2.0 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ....................................................................................................... 5 3.0 BENEFICIAL USES AND STAKEHOLDER GROUPS ................................................................... -

Go Viral 9-5.Pdf

Hello fellow musicians, artists, rappers, bands, and creatives! I’m excited you’ve decided to invest into your music career and get this incredible list of music industry contacts. You’re being proactive in chasing your own goals and dreams and I think that’s pretty darn awecome! Getting your awesome music into the media can have a TREMENDOUS effect on building your fan base and getting your music heard!! And that’s exactly what you can do with the contacts in this book! I want to encourage you to read the articles in this resource to help guide you with how and what to submit since this is a crucial part to getting published on these blogs, magazines, radio stations and more. I want to wish all of you good luck and I hope that you’re able to create some great connections through this book! Best wishes! Your Musical Friend, Kristine Mirelle VIDEO TUTORIALS Hey guys! Kristine here J I’ve put together a few tutorials below to help you navigate through this gigantic list of media contacts! I know it can be a little overwhelming with so many options and places to start so I’ve put together a few videos I’d highly recommend for you to watch J (Most of these are private videos so they are not even available to the public. Just to you as a BONUS for getting “Go Viral” TABLE OF CONTENTS What Do I Send These Contacts? There isn’t a “One Size Fits All” kind of package to send everyone since you’ll have a different end goal with each person you are contacting. -

Where Art Meets Technology and Science Introducing the New Cal Poly Center for Expressive Technologies

CAL POLY COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS LEARN / LEAD / LIVE / SUMMER 2014 Where Art Meets Technology and Science Introducing the new Cal Poly Center for Expressive Technologies Inside 3: Faculty and students make their mark / 10: Documenting ‘Lives Well Lived’ / 12: Cal Poly alumna thrives as Dwell Media president / 14: Then-and-now glimpses around campus / Welcome Dear CLA Alumni and Friends: ince arriving at Cal Poly, I have been im- pressed by the close-knit community that S comprises the College of Liberal Arts — both on and off campus. The College of Liberal Arts’ alumni and friends that I have met are just as pas- impact sionate about Cal Poly now, if not more so, as when Summer 2014 they first stepped on campus. Elizabeth Lowham, This is a testament to our outstanding faculty Dean’s Office CET Director and staff, who truly care about students’ academic, 805-756-2359 professional and personal success. Your achievements Editor have established the high value of a liberal arts degree Katie VanMeter Features at Cal Poly. The col- [email protected] lege’s respect for you — Center for Expressive Technologies (CET) and our continuing Staff Writer Crystal Herrera Cal Poly’s new academic enterprise reimagines commitment to 6 — students require that the relationship between technology and the arts. Design we sustain across DCP / dcpubs.com Learning From ‘Lives Well Lived’ future generations Cal Poly photography Professor Sky 10 of students the Do we have your current Bergman showcases a generation aging with excellence for which contact information? grace and purpose. we are known. -

Cal Poly Magazine, Fall 2000

ROM OUR READERS ditor's Note: The following letters on the spring 2000 Especially interesting are the feature articles Eissue were edited faT brevity. recognizing the various colleges. [My wife and I have a personal interest] in bio/agricultural engineering I just wanted to thank you for Cal Poly Magazine. The majors, since our son and son-in-law graduated in the articles were so interesting and well written I could mid-70s along with a daughter-in-law and daughter not put [the issue] down once I started reading. I am in home economics. The addition over the years of especially excited about both MaxiVision (being a bit other disciplines [enhancing] the effectiveness of the of a movie nut) and the plastic products of the future university is well and good, [proViding] a well (especially since I work in the electronics industry in rounded offering ... , but [I was disappointed to see] Silicon Valley). It really is exciting to learn about all the feature on [alumnus Al Yankovic], who is the great things going on at Cal Poly and in the lives pursuing a career in music that appears to feed on the of alumni. Thank you so much for producing such a rock culture scene. In my opinion thiS gives a wrong wonderful journal. impression of the traditional and important values - Shari Mullen (POLS '82) that Cal Poly represents ... as a university that upholds a "hands-on" approach in learning. - Jack H. Nikkel From Our Readers continued on page 2 ON TN COVER Environmental Horticultural Science Professor Tom Eltzroth (center) goes over an outline ofplantings for the College of Agriculture's Leaning Pine Arboretum with senior Chris Wassenberg (EHS '01) and alumna Meg Abel (EHS '00). -

Owned Radio Stations College, University and School -Owned Radio Stations

College, University and School -Owned Radio Stations College, University and School -Owned Radio Stations 'KRUA FM Anchorage AK 'KUOP(FM) Stockton CA 'KDIC(FM) Grinnell IA WBSW(FM) Marion IN 'WKKL(FM) West Barnstable MA 'KCUK FM Chevak AK 'KKTO FM Tahoe City CA 'KSTM(FM) Indianola IA WEST(FM) Muncie IN WBUR(AM) West Yarmouth MA 'KDLG AM Dillingham AK 'KCPB FM Thousand Oaks CA 'KRUI- M Iowa City IA WVWDS (FM) Muncie IN WSKB(FM) Westfield MA 'KSUA FM Fairbanks AK *KCSS FM Turlock CA 'WSUI(AM) Iowa City IA WWHI(FM) Muncie IN WCHC (FM) Worcester MA 'KUAB FM Fairbanks AK 'KSAK FM Walnut CA 'KUNY(FM) Mason City IA WNAS(FM) New Albany IN WBJC(M) Baltimore MD 'KUAC FM) Fairbanks AK 'KASF FM Alamosa CO 'KRNL -FM Mount Vernon IA WBKE -FM North Manchester IN WBYO(FM) Baltimore MD 'KUHB AM) St. Paul AK 'KRCC(FM) Colorado Springs CO 'KIGC(FM) Oskaloosa IA WSNDFM Notre Dame IN WEAA(FM) Baltimore MD 'KUHB -FM St. Paul AK `KTLF(FFM Colorado Springs CO 'KCUIR(FM) Pella IA WEEM(FM) Pendleton IN WJHU -FM Baltimore MD 'KSID(FM) Cortez CO 'KDC (FM) Sioux Center IA WBSJ(FM) Portland IN WHFC(FM) Bel Air MD WBHM(FM))M) Birmingham AL ' KDUR(FM) Durango CO 'KMSC(FFM)) Sioux City IA WPUM(F Rensselaer IN 'WMUC -FM College Park MD WGIB(FM ) Birmingham AL 'KCSU -FM Fort Collins CO 'KWIT M) Sioux City IA INECI(FM) Richmond IN WOEL -FM Elkton MD WJSR(FM) Birmingham AL `KDRH(FM) Glenwood Springs CO 'KNW AM Waterloo IA WVXR (FM) Richmond IN WMTBFM Emmittsburg MD WVSU -FM Birmingham AL 'KCIC(FM) Grand Junction CO 'KWAR FM Waverly IA WETL(M) South Bend IN WFWM(FM) Frostburg -

Radio Airplay Report: 12/11/2009

Radio Airplay Report: 12/11/2009 Ancient Future Mariah Parker Matthew Montfort POB 264, Kentfield CA 94914-0264 USA Planet Passion Sangria Seven Serenades 415-459-1892 • [email protected] (AF 2010) (AF 2017) (AF 2008) Radio-Public 3/25/2009 Add to playlist Music Director c/o KRBD Ketchikan, AK 99901 Radio-Public 3/9/2009 3/9/2009 3/9/2009 Add to playlist Add to playlist Add to playlist Melissa Marconi-Wenzel Music Director KCAW-FM Raven Radio Foundation Sitka, AK 99835 Radio-Public 7/20/2009 7/20/2009 7/20/2009 add to playlist add to playlist add to playlist Jeff Brown Program / Music Director - Rain Country KTOO Juneau, AK 99801 Radio-Public 4/1/2009 4/1/2009 Add to playlist Add to playlist Bud Johnson Acoustic Accents KUAC-FM, Community Radio of Alaska Fairbanks, AK 99775 Radio-Public 2/8/2009 2/8/2009 2/8/2009 Add to playlist Add to playlist Add to playlist Andy Blossy The Ancient Future 'aesthetic' is real Nightlight congruent within the intentions of KUAC-FM, Community Radio of Alaska 'Nightlight'. Fairbanks, AK 99775 Radio-Public 5/20/2009 5/20/2009 5/20/2009 add to music library add to music library add to music library Music Director for NAR Programming Community Radio of Alaska, Inc. KTNA-FM Talkeetna, AK 99676 Radio Airplay Report: 12/11/2009 Ancient Future Mariah Parker Matthew Montfort POB 264, Kentfield CA 94914-0264 USA Planet Passion Sangria Seven Serenades 415-459-1892 • [email protected] (AF 2010) (AF 2017) (AF 2008) Writer-Freelance 6/16/2009 Add to music library, jazz Robert Ambrose The Rhythm Connection KTNA-FM -

FY 2004 AM and FM Radio Station Regulatory Fees

FY 2004 AM and FM Radio Station Regulatory Fees Call Sign Fac. ID. # Service Class Community State Fee Code Fee Population KA2XRA 91078 AM D ALBUQUERQUE NM 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KAAA 55492 AM C KINGMAN AZ 0430$ 525 25,001 to 75,000 KAAB 39607 AM D BATESVILLE AR 0436$ 625 25,001 to 75,000 KAAK 63872 FM C1 GREAT FALLS MT 0449$ 2,200 75,001 to 150,000 KAAM 17303 AM B GARLAND TX 0480$ 5,400 above 3 million KAAN 31004 AM D BETHANY MO 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KAAN-FM 31005 FM C2 BETHANY MO 0447$ 675 up to 25,000 KAAP 63882 FM A ROCK ISLAND WA 0442$ 1,050 25,001 to 75,000 KAAQ 18090 FM C1 ALLIANCE NE 0447$ 675 up to 25,000 KAAR 63877 FM C1 BUTTE MT 0448$ 1,175 25,001 to 75,000 KAAT 8341 FM B1 OAKHURST CA 0442$ 1,050 25,001 to 75,000 KAAY 33253 AM A LITTLE ROCK AR 0421$ 3,900 500,000 to 1.2 million KABC 33254 AM B LOS ANGELES CA 0480$ 5,400 above 3 million KABF 2772 FM C1 LITTLE ROCK AR 0451$ 4,225 500,000 to 1.2 million KABG 44000 FM C LOS ALAMOS NM 0450$ 2,875 150,001 to 500,000 KABI 18054 AM D ABILENE KS 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KABK-FM 26390 FM C2 AUGUSTA AR 0448$ 1,175 25,001 to 75,000 KABL 59957 AM B OAKLAND CA 0480$ 5,400 above 3 million KABN 13550 AM B CONCORD CA 0427$ 2,925 500,000 to 1.2 million KABQ 65394 AM B ALBUQUERQUE NM 0427$ 2,925 500,000 to 1.2 million KABR 65389 AM D ALAMO COMMUNITY NM 0435$ 425 up to 25,000 KABU 15265 FM A FORT TOTTEN ND 0441$ 525 up to 25,000 KABX-FM 41173 FM B MERCED CA 0449$ 2,200 75,001 to 150,000 KABZ 60134 FM C LITTLE ROCK AR 0451$ 4,225 500,000 to 1.2 million KACC 1205 FM A ALVIN TX 0443$ 1,450 75,001 -

Music and Radio Preferences on the Cal Poly Campus

Music and Radio Preferences on the Cal Poly Campus A Senior Project presented to the Faculty of the Statistics Department California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Science in Statistics by Rory Bloch June, 2011 © 2011 Rory Bloch Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 2 2.) Methods and Materials ........................................................................................................................ 3 2.1 Data Collection .................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1.1 Design of Questionnaire .................................................................................................................. 3 2.1.2 Sampling Design ............................................................................................................................... 5 2.1.3 Challenges with Data Collection and analysis .................................................................................. 8 Data Analysis: ............................................................................................................................................ 9 3.1 Sample Demographics: ....................................................................................................................... 9 3.2 Summary Statistics ...........................................................................................................................