Restructuring Symphony Orchestras Through Diversity and Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UPDATED January 13, 2015 January 7, 2015 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] ALAN GILBERT AND THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC Alan Gilbert To Conduct SILK ROAD ENSEMBLE with YO-YO MA Alongside the New York Philharmonic in Concerts Celebrating the Silk Road Ensemble’s 15TH ANNIVERSARY Program To Include The Silk Road Suite and Works by DMITRI YANOV-YANOVSKY, R. STRAUSS, AND OSVALDO GOLIJOV February 19–21, 2015 FREE INSIGHTS AT THE ATRIUM EVENT “Traversing Time and Trade: Fifteen Years of the Silkroad” February 18, 2015 The Silk Road Ensemble with Yo-Yo Ma will perform alongside the New York Philharmonic, led by Alan Gilbert, for a celebration of the innovative world-music ensemble’s 15th anniversary, Thursday, February 19, 2015, at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, February 20 at 8:00 p.m.; and Saturday, February 21 at 8:00 p.m. Titled Sacred and Transcendent, the program will feature the Philharmonic and the Silk Road Ensemble performing both separately and together. The concert will feature Fanfare for Gaita, Suona, and Brass; The Silk Road Suite, a compilation of works commissioned and premiered by the Ensemble; Dmitri Yanov-Yanovsky’s Sacred Signs Suite; R. Strauss’s Death and Transfiguration; and Osvaldo Golijov’s Rose of the Winds. The program marks the Silk Road Ensemble’s Philharmonic debut. “The Silk Road Ensemble demonstrates different approaches of exploring world traditions in a way that — through collaboration, flexible thinking, and disciplined imagination — allows each to flourish and evolve within its own frame,” Yo-Yo Ma said. -

The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners

Published: Nzinga, K.L.K., & Medin, D.L. (2018). The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners. Journal of Cognition and Culture, 312-342. http://booKsandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/15685373-12340033 The Moral Priorities of Rap Listeners Kalonji L.K. NZINGA Douglas L. MEDIN Northwestern University A Cross-cultural approach to moral psychology starts from researchers withholding judgments about universal right and wrong and instead exploring community members’ values and what they subjeCtively perCeive to be moral or immoral in their loCal Context. This study seeks to identify the moral ConCerns that are most relevant to listeners of hip- hop music. We use validated psyChologiCal surveys inCluding the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek 2009) to assess whiCh moral ConCerns are most central to hip-hop listeners. Results show that hip-hop listeners prioritize concerns of justiCe and authentiCity more than non-listeners and deprioritize ConCerns about respeCting authority. These results show that the ConCept of the “good person” within the hip-hop subculture is fundamentally a person that is oriented towards soCial justiCe, rebellion against the status quo, and a deep devotion to keeping it real. Results are followed by a disCussion of the role that youth subCultures have in soCializing young people to prioritize Certain virtues over others as they develop their moral identity. 1. Introduction Many AmeriCan rappers inCluding KendriCk Lamar (2010), Snoop Dogg (2015), and Busta Rhymes (2006) have delivered the following CatCh phrase in their lyriCs: “You Can take me out the hood, but you Can’t take the hood out of me.” They proClaim that there are Certain aspeCts of the “hood” lifestyle and value system that, onCe they are part of you, direCt how you perCeive the world and behave in it. -

Windward Passenger

MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE BURRELL WINDWARD PASSENGER PHEEROAN NICKI DOM HASAAN akLAFF PARROTT SALVADOR IBN ALI Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : PHEEROAN aklaff 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : nicki parrott 7 by jim motavalli General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : dave burrell 8 by john sharpe Advertising: [email protected] Encore : dom salvador by laurel gross Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : HASAAN IBN ALI 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : space time by ken dryden US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIVAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD ReviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 43 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Event Calendar 44 Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Kevin Canfield, Marco Cangiano, Pierre Crépon George Grella, Laurel Gross, Jim Motavalli, Greg Packham, Eric Wendell Contributing Photographers In jazz parlance, the “rhythm section” is shorthand for piano, bass and drums. -

702 Steelo Remixes Mp3, Flac, Wma

702 Steelo Remixes mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop / Funk / Soul Album: Steelo Remixes Country: US Released: 1996 Style: RnB/Swing, Rhythm & Blues MP3 version RAR size: 1451 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1821 mb WMA version RAR size: 1114 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 729 Other Formats: AA MP4 AHX AC3 AU XM MMF Tracklist Hide Credits Steelo (J-Dub Mix Edit) 1 4:00 Co-producer – Kenny BurnsFeaturing – Brad Dacus, Missy ElliottProducer – Dent*, J-Dub* Steelo (Timbaland Mix Edit) 2 4:03 Featuring – Missy ElliottProducer – Timbaland Steelo (Cali Mix) 3 4:09 Producer – Timbaland Steelo (Rashad Remix) 4 Arranged By – Missy Elliott, Rashad SmithCo-producer – Armando ColonProducer – Rashad 3:31 SmithWritten By – Missy Elliott, Rashad Smith Steelo (LP Edit) 5 Featuring – Missy ElliottProducer – Chad "Dr. Ceuss" Elliott*, George PearsonWritten By – 4:00 Chad Elliott, George Pearson, Gordon Sumners* Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Motown Record Company, L.P. Marketed By – Motown Record Company, L.P. Copyright (c) – Biv Ten Records Phonographic Copyright (p) – Biv Ten Records Credits A&R – Derek "Chuck Bone" Osorio*, Todd "Bozak" Russaw* Administrator – Steve Cook Executive Producer – Michael Bivins, Todd Russaw Management – Andre Harrell Notes LP Version appears on the 702 "No Doubt" Vinyl, CD & Cassette 314530738-1/2/4 Steelo contains a sample from "Voices Inside My Head" written by Gordon Sumner ©℗ 1996 Biv Ten Records, a Joint Venture of Motown Record Company, L.P., and Biv Ventures, Inc. Manufactured and Marketed by Motown Record Company, L.P., 825 8th Ave., New York, NY 10019- USA. All Rights Reserved. Unauthorized duplication is a violation of applicable laws. -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

ölver ine MORRIS BROWN COLLEGE “Dedicated to Educating the Leaders of Tomorrow” Herndon Stadium - A mnnument to self help by Herman “Skip” Mason, Jr. ‘84 College Historian/Archivist estled in the Vine City community behind the Morris Brown College campus was a huge rock pile surrounded by land virtually unfit for cultivation and building. The open field was adjacent to the home of many Vine City residents including the home of the President of the Morris Brown College and the palatial home of the Herndon family. It was in 1946 that work began to carve and sculpt this gigantic rock into a football stadium. Its namesakes Alonzo F and Norris B. Herndon, founder and son of Atlanta Life Insurance Company ironically were pillars in the Mayor Bill Campbell, Mayor of Atlanta gives Dr. Samuel D. Jolley Jr., President of Morris Brown College, a Proclamation during the dedication of the new Herndon Football Stadium. community. Why was there a need for a small liberal black arts SYMBOLISM college to have a stadium of its own? In the late 1890’s, Morris Brown became An Open Letter involved in athletic Let our children competition. In 1911, the school organized its first to the Morris football team. The team was coached by J.S. Jackson and decide later D.H. Sims and the first Brown Campus team consisted of Nathaniel by Charlton Pharris Flipper, S.W. Prioleux, Willie crosses and crucifixes to rasping for the Ed Grant, Allen Cooper, Fred logos, they tangify the Wiley, Milton Carnes, meaning of symbols in intangible. They cast Community Americus Lee, David Gour lives is an elusive reach.thoughts and values into Townsley, and John Corley. -

Combined Guide for Web.Pdf

2015-16 American Preseason Player of the Year Nic Moore, SMU 2015-16 Preseason Coaches Poll Preseason All-Conference First Team (First-place votes in parenthesis) Octavius Ellis, Sr., F, Cincinnati Daniel Hamilton, So., G/F, UConn 1. SMU (8) 98 *Markus Kennedy, R-Sr., F, SMU 2. UConn (2) 87 *Nic Moore, R-Sr., G, SMU 3. Cincinnati (1) 84 James Woodard, Sr., G, Tulsa 4. Tulsa 76 5. Memphis 59 Preseason All-Conference Second Team 6. Temple 54 7. Houston 48 Troy Caupain, Jr., G, Cincinnati Amida Brimah, Jr., C, UConn 8. East Carolina 31 Sterling Gibbs, GS, G, UConn 9. UCF 30 Shaq Goodwin, Sr., F, Memphis 10. USF 20 Shaquille Harrison, Sr., G, Tulsa 11. Tulane 11 [*] denotes unanimous selection Preseason Player of the Year: Nic Moore, SMU Preseason Rookie of the Year: Jalen Adams, UConn THE AMERICAN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE Table Of Contents American Athletic Conference ...............................................2-3 Commissioner Mike Aresco ....................................................4-5 Conference Staff .......................................................................6-9 15 Park Row West • Providence, Rhode Island 02903 Conference Headquarters ........................................................10 Switchboard - 401.244-3278 • Communications - 401.453.0660 www.TheAmerican.org American Digital Network ........................................................11 Officiating ....................................................................................12 American Athletic Conference Staff American Athletic Conference Notebook -

NSCMF 2014 Pressreport

josephcorreia A&E COLUMNS Home News Business Sports A&E Life & Style Opinion Real Estate Cars Jobs 2014 North Shore Chamber Music Festival preview Custom Banner - $8.99 vistaprint.com Buy Quality Custom Banners Today. Personalize & Order Online Now. Email Tweet 11 Recommend 68 Pinterest 0 2 1 2 next | single page Violinist Vadim Gluzman and his wife, pianist Angela Yoffe are rehearsing in Chicago on Tuesday, May 27, 2014 for a performance at the North Shore Chamber Music Festival. Gluzman is playing rare violin, the "ex-Auer" 1690 Stradivarius. (Zbigniew Bzdak, Chicago Tribune / May 26, 2014) John von Rhein 1:42 p.m. CDT, June 3, 2014 The North Shore Chamber Music Festival is a mom-and-pop Chicago classical operation that thinks big. Very big. Internationally big. The event's directors, the celebrated violinist Vadim Gluzman and his wife, pianist Angela Yoffe, take time out from their busy solo and duo careers each year at this time to put on the BRAND PUBLISHING This is sponsored content. ? three-day festival at a church near their Northbrook home. WINDY CITY HAIR Every season they invite musician friends from near and far to share their love of the rich After hair-loss chamber repertory with the festival's appreciative audience. battle, resolution for female alopecia This year's roster includes such admired artists as violinist JOHN VON RHEIN sufferer Anne Akiko Meyers, pianist Alessio Bax, cellist Wendy Warner and pianist-conductor Andrew Litton, along with REAL ESTATE INSIDER student musiciansNorth Shore from ChamberChicago's Betty Music Haig Festival Academy • of P.O. -

Download the Program Here

Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre thanks the following organizations and individuals for their support of Open Air: A Series in Celebration of the Performing Arts. SERIES SPONSORS MEDIA SPONSOR FESTIVAL SPONSORS Vivian and Bill Benter Ryan Memorial Foundation CELEBRATION SPONSORS 84 Lumber and Nemacolin Steffie Bozic The Remmel Foundation Charlotte and David Stephenson EVENT SPONSORS Citizens DDI Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council Hefren - Tillotson, Inc. Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield Dorrit and David Tuthill 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre was 5 Message from the Artistic Director founded by Loti Falk Gaffney 6 Message from Series Sponsor BNY Mellon and Nicolas Petrov in 1969. 8 Message from Safety Sponsor MSA Safety PBT’s Artistic 10 Program A - Casting and Credits Directors: Nicolas Petrov 12 Program A - Program Notes 1969-1977 John Gilpin 15 Program B - Casting and Credits 1977-1978 17 Program B - Program Notes Patrick Frantz 1978-1982 20 Orchestra - Musicians Patricia Wilde 1982-1997 22 Orchestra - Program Notes Terrence S. Orr 1997-2020 25 Participating Organizations Susan Jaffe 2020-present 26 Keep Us Dancing Honor Roll 28 Board of Directors 31 Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre Staff MISSION STATEMENT To be Pittsburgh’s source and ambassador for extraordinary ballet experiences that give life to the classical tradition, nurture new ideas and, above all, inspire. Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre is supported, in part, by the National Endowment for the Arts, a federal agency; the Pennsylvania Official Piano of Council on the Arts, a state agency; -

Art Works Grants

National Endowment for the Arts — December 2014 Grant Announcement Art Works grants Discipline/Field Listings Project details are as of November 24, 2014. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Art Works grants supports the creation of art that meets the highest standards of excellence, public engagement with diverse and excellent art, lifelong learning in the arts, and the strengthening of communities through the arts. Click the discipline/field below to jump to that area of the document. Artist Communities Arts Education Dance Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Page 1 of 168 Artist Communities Number of Grants: 35 Total Dollar Amount: $645,000 18th Street Arts Complex (aka 18th Street Arts Center) $10,000 Santa Monica, CA To support artist residencies and related activities. Artists residing at the main gallery will be given 24-hour access to the space and a stipend. Structured as both a residency and an exhibition, the works created will be on view to the public alongside narratives about the artists' creative process. Alliance of Artists Communities $40,000 Providence, RI To support research, convenings, and trainings about the field of artist communities. Priority research areas will include social change residencies, international exchanges, and the intersections of art and science. Cohort groups (teams addressing similar concerns co-chaired by at least two residency directors) will focus on best practices and develop content for trainings and workshops. -

Chicago Jazz Festival Spotlights Hometown

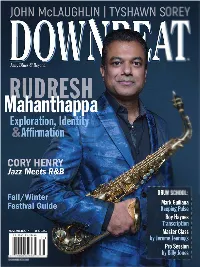

NOVEMBER 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, -

2011 Next Wave Festival SEP 2011

2011 Next Wave Festival SEP 2011 Donald Baechler, Red + Blue Rose (detail), 2011 BAM 2011 Next Wave Festival sponsor Published by: BAM 2011 Next Wave Festival Brooklyn Academy of Music presents Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Awakening: Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board A Musical Meditation Karen Brooks Hopkins, President on the Anniversary of 9/11 Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Sep 21—24, 2011 at 7:30pm Approximate running time: 90 minutes, no intermission Kronos Quartet Violin David Harrington Violin John Sherba Viola Hank Dutt Cello Jeffrey Zeigler With special guest Brooklyn Youth Chorus, conducted by Dianne Berkun Scenic and lighting design by Laurence Neff Audio engineer Brian Mohr Technical associate Calvin Ll. Jones Awakening was first performed on September 11, 2006, at Herbst Theatre in San Francisco, California. BAM 2011 Next Wave Festival sponsor The 2011 Richard B. Fisher Next Wave Award honors the Kronos Quartet and its production of Awakening. Leadership support for the Next Wave Festival is provided by The Ford Foundation. Leadership support for Awakening provided by Goldman Sachs Gives at the recommendation of R. Martin Chavez. Awakening A Musical Meditation on the Anniversary of 9/11 I. Dmitri Yanov-Yanovsky Awakening* (Uzbekistan) Unknown (arr. Ljova & Kronos) Oh Mother, the Handsome Man Tortures Me+ (Iraq) Traditional (arr. Jacob Garchik) Lullaby+ (Iran) Ram Narayan (arr. Kronos, transc. Ljova) Raga Mishra Bhairavi: Alap+ (India) II. Einstürzende Neubauten Armenia+ (Germany) (arr. Paola Prestini & Kronos) John Oswald Spectre* (Canada) Michael Gordon Selections from The Sad Park* (United States) Part 1 two evil planes broke in little pieces and fire came Part 4 and all the persons that were in the airplane died III. -

COMING SOON COMMUNICATION • Design : Fabrication Maison / TROÏKA

Textes : COMING SOON COMMUNICATION • Design : Fabrication Maison / TROÏKA METROPOLITAN FILMEXPORT présente un film ROGUE PICTURES et BOB YARI PRODUCTIONS Une production PILOT BOY/KABUKI BROTHERS FILMS En association avec PARTIZAN FILMS un film de MICHEL GONDRY (DAVE CHAPPELLE’S BLOCK PARTY) Avec KANYE WEST, MOS DEF, TALIB KWELI, COMMON, THE FUGEES, DEAD PREZ, ERYKAH BADU, JILL SCOTT, THE ROOTS, DAVE CHAPPELLE Superviseur de la musique : COREY SMYTH Montage : SARAH FLACK, JEFF BUCHANAN Décors : LAURI FAGGIONI Directrice de la photographie : ELLEN KURAS, A.S.C. Un film produit par MUSTAFA ABUELHIJA, JULIE FONG et DAVE CHAPPELLE & BOB YARI Durée : 1 h 43 min SORTIE NATIONALE LE 6 SEPTEMBRE DISTRIBUTION RELATIONS PRESSE METROPOLITAN FILMEXPORT MICHEL BURSTEIN / BOSSA NOVA 29, rue Galilée - 75116 Paris 32, boulevard Saint Germain - 75005 Paris Tél.: 01 56 59 23 25 E-mail : [email protected] Fax : 01 53 57 84 02 Tél.. : 01 43 26 26 26 - www.bossa-nova.info PROGRAMMATION PARTENARIATS RÉGION PARIS GRP-EST-NORD ET PROMOTION Tél.: 01 56 59 23 25 AGENCE MERCREDI RÉGION MARSEILLE LYON-BORDEAUX Tél.: 01 56 59 66 66 Tél. : 05 56 44 04 04 www.metrofilms.com Fax : 01 56 59 66 67 Vous allez vivre une journée à part. BLOCK PARTY est un événement musical unique autour d'une personnalité hors norme, dans un contexte historique filmé par l'un des visionnaires les plus atypiques de notre époque. Vous vous dites que ça fait beaucoup et pourtant, c'est vrai ! BLOCK PARTY est l'histoire d'un concert caméras sur les répétitions privées des mémorable organisé à Brooklyn à l'initiative musiciens, et suivi Dave Chappelle dans sa de l'humoriste américain Dave Chappelle.