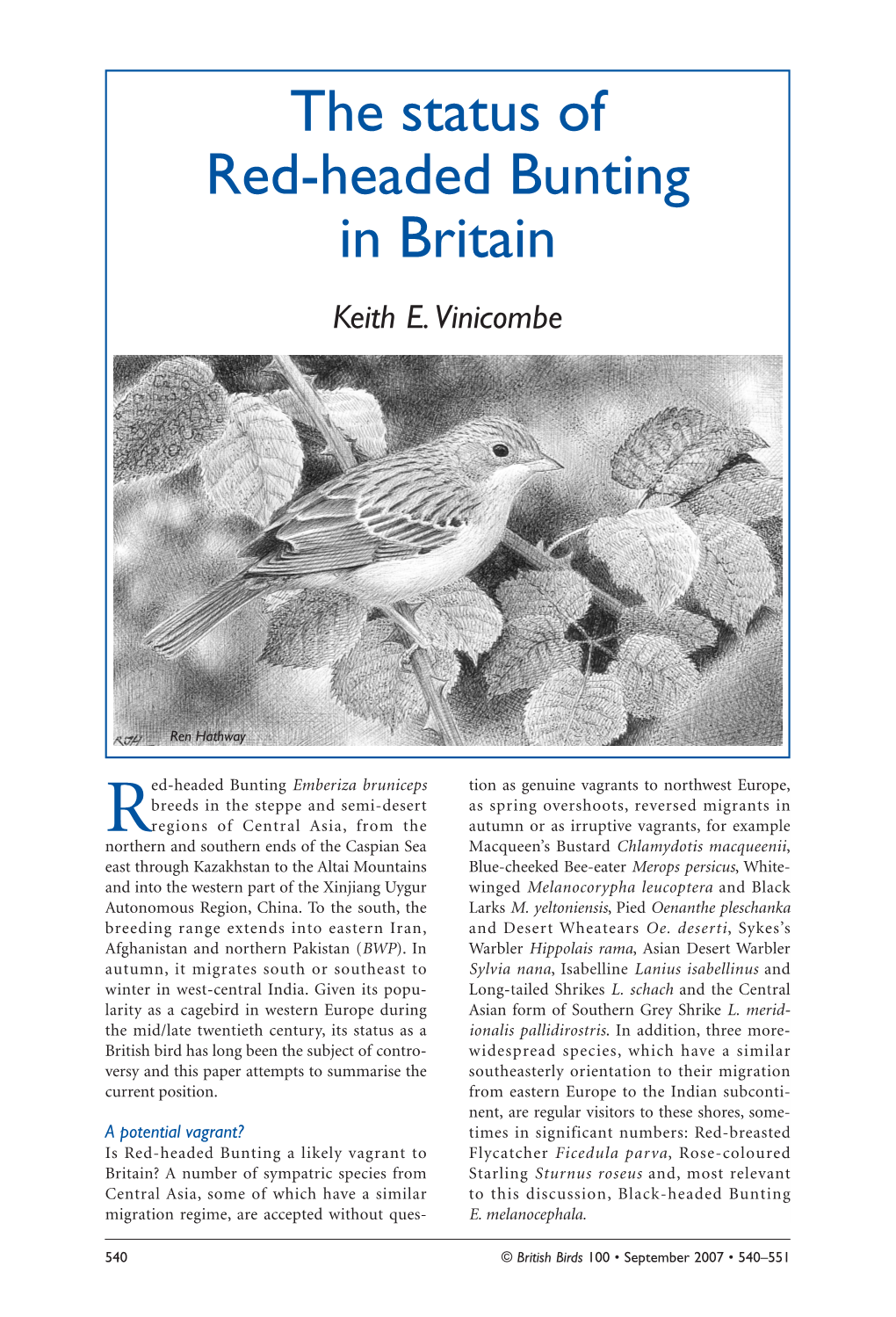

The Status of Red-Headed Bunting in Britain Keith E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird-O-Soar Note on First Record of Asian Desert Warbler Sylvia Nana at Mokarsagar Wetland Complex, Gujarat, India

#33 Bird-o-soar 21 September 2019 Note on first record of Asian Desert Warbler Sylvia nana at Mokarsagar Wetland Complex, Gujarat, India Asian Desert Warbler Sylvia nana photographed from Gosabara Wetland. The Mokarsagar Wetland Complex, formally It is dominated by sedges and other known as the Gosabara Wetland, is located hydrophytic vegetation (Nagar 2017). in the Porbandar district of the Kathiawar peninsula in the state of Gujarat, India. The wetland is a lifeline for the community and for its dependent biodiversity, The Mokarsagar Wetland Complex, comprising both flora (mangrove, formed by the Karli Recharge Reservoir macroalgae & macrophytes) and fauna and Karli Tidal Regulator, contains a group (birds, reptiles, insects, & mammals). of wetlands, including the Medha creek, During winter season, many migratory birds Kuchhadi, Subhashnagar, Zavar, Kurly I, such as Demoiselle Crane, Common Crane, Karly II, Vanana, Dharampur, Gosabara, Pelican, and many species of Duck can be Bhadarbara, Mokarsagar, Bardasagar, and seen here. After the water dries up, birds Amipur (Nagar 2017). The Mokarsagar such as Larks, Pipits, and Pratincole can Wetland Complex is a combination be seen. At 14:39hr on 26 January, 2017, of estuary and fresh-water habitats. the author was carrying out vegetation Zoo’s Print Vol. 34 | No. 9 14 #33 Bird-o-soar 21 September 2019 quadrat sampling at the Prosopis Island bird was strengthened by its longitudinal in Gosabara wetland. Suddenly, a bird tail-flickering behaviour observed in the that looked very different, flew across field. the authors and perched on a branch of Suaeda nudiflora. Sylvia nana is an arid bird species which breeds through North and East Caspian The author followed the bird and observed Sea coasts and Northeast Iran, East to it for a few seconds and could photograph Central and South Mongolia and Northwest it before it flew out of sight. -

182 Reference Asian Desert Warbler Sylvia Nana in Lava, West Bengal

182 Indian Birds VOL. 15 NO. 6 (PUBL. 15 JUNE 2020) collected by S. D. Ripley in Nagaland on 03 December 1950 (Yale Peabody Museum 2017), and the other (UMMZ birds #178643) collected by Walter Koelz in Karong, Manipur, on 23 November 1950 (University of Michigan Museum of Zoology 2019). A search of images posted on www.orientalbirdimages.org and specimens collected on portal.vertnet.org indicate that while dabryii has been recorded in China and Thailand, isolata has been recorded in Myanmar, and Meghalaya, Manipur, Nagaland, Chowdhury Roy Soumen and Mizoram in India. Therefore, it seems that during its winter/ seasonal movements, the distribution of dabryii may be limited to an area where it meets isolata: south of the Brahmaputra in India on the west, and Myanmar to the east. We could not trace any photographs of this race from India, and hence ours appears to be a first record after nearly 70 years from India. 235. Asian Desert Warbler showing clearly the yellow iris. Authors thank Praveen J. for his guidance and suggestions for this manuscript. The Asian Desert Warbler is a bird of the arid landscape, breeding through the northern and eastern regions of the Caspian Sea coasts, north-eastern Iran, much of Mongolia, and north- Reference western China. Its non-breeding range extends from north-eastern Rasmussen, P. C. & Anderton, J. C. (2012). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Vol. Africa, mostly along the Red Sea coast, Arabia, and farther eastwards 2. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions, Washington D. C. and Barcelona. till north-western India (Aymí et al. -

Tropical Birding Israel Tour

Tropical Birding Trip Report Israel March, 2018 Tropical Birding Israel Tour March 10– 22, 2018 TOUR LEADER: Trevor Ellery Report and photos Trevor Ellery, all photos are from the tour. Green Bee-eater. One of the iconic birds of southern Israel. This was Tropical Birding’s inaugural Israel tour but guide Trevor Ellery had previously lived, birded and guided there between 1998 and 2001, so it was something of a trip down memory lane for the guide! While Israel frequently makes the international news due to ongoing tensions within the country, such problems are generally concentrated around specific flashpoints and much of the rest of the country is calm, peaceful, clean and modern. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Israel March, 2018 Our tour started on the afternoon of the 10th where, after picking up the group at Ben Gurion airport near Tel Aviv, we headed north along the coastal strip, collecting our local guide (excellent Israeli birder Chen Rozen) and arrived at Kibbutz Nasholim on the shores of the Mediterranean with plenty of time for some local birding in the nearby fishponds. Spur-winged Lapwing – an abundant, aggressive but nevertheless handsome species wherever we went in Israel. Hoopoe, a common resident, summer migrant and winter visitor. We saw this species on numerous days during the tour but probably most interesting were quite a few birds seen clearly in active migration, crossing the desolate deserts of the south. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Israel March, 2018 We soon managed to rack up a good list of the commoner species of these habitats. -

Status of the Asian Desert Warbler Sylvia Nana in Uttarakhand, India

Correspondence 125 locations in Maharashtra and West Bengal but surprisingly, not We thank the Makunda Christian Hospital, which runs the from northeast India. Online sites such as OBI, eBird, Xeno-canto, Makunda Nature Club, for the use of camera and GPS device and IBC, and Facebook groups such as “Ask IDs of Indian Birds” used in this observation and to Biswapriya Rahut for providing his “Birds of Eastern India”, and “Indian Birds” were searched and insights on northern Bengal records. previously documented records of observations from India are recorded in Table 1. References Abdulali, H., 1987. A catalogue of the birds in the collection of the Bombay Natural History Society-32. Muscicapidae (Turdinae). Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 84 (1): 105–125. Adams, A. L., 1859. The birds of Cashmere and Ladakh. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1859 (395): 169–190 (with one pl. CLVI). Basu, A., 2014. Website URL: https://www.facebook.com/photo. php?fbid=564291623671308. [Accessed on 24 August 2019.] Choudhury, A., 2003. Birds of Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary and Sessa Orchid Sanctuary, Arunachal Pradesh, India. Forktail 19: 1–13. Collar, N., 2019. Siberian Blue Robin (Larvivora cyane). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A., & de Juana, E., (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Website URL: https://www.hbw.com/ node/58457. [Accessed on 06 March 2019.] Deshmukh, P., 2011. First record of Siberian Blue Robin Luscinia cyane from Nagpur, central India. Indian BIRDS 7 (4): 111. Dutta, M., 2017. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S33856891. -

Bird Red List and Its Future Development in Mongolia S

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Halle-Wittenberg Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 2012 Bird Red List and Its Future Development in Mongolia S. Gombobaatar National University of Mongolia, [email protected] D. Samiya National University of Mongolia Jonathan M. Baillie Zoologial Society of London, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol Part of the Animal Law Commons, Animal Studies Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Environmental Sciences Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Ornithology Commons, and the Other Animal Sciences Commons Gombobaatar, S.; Samiya, D.; and Baillie, Jonathan M., "Bird Red List and Its Future Development in Mongolia" (2012). Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298. 18. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. -

Mongolia: the Gobi Desert, Steppe & Taiga 2018

Field Guides Tour Report Mongolia: The Gobi Desert, Steppe & Taiga 2018 May 31, 2018 to Jun 17, 2018 Phil Gregory & Bayanaa For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Demoiselle Cranes put on a wonderful show for us Elsen Tasarkhai. In all, we saw these beautiful birds on six days of the tour. Photo by participant Laszlo Czinege. This was the second Field Guides tour to Mongolia, covering many of the key sites and habitats in central, southern and northern Mongolia, including steppe, desert and boreal forest, and we succeeded very nicely. It was a late, dry and rather cold spring here despite good snowfall over the winter, so water levels in the wetlands were low and some species were scarce, but breeding was certainly in full swing. Staying primarily in ger camps was fun, but you have to get used to the low doorways and starlit nocturnal treks to the bathroom. Most came in early to get oriented, and also do a cultural tour, which included the National Museum, the brilliant UNESCO World Heritage lama temple at Choisin (with those wonderful metal 18th century sculptures by Zanabazar, the Mongolian Michelangelo), and a fantastic concert that included extraordinary throat singing, skilled musicians with horsehead fiddles, folk dancers and a contortionist, all well worth doing and recommended. We went to Songino and some riparian habitat along the Tuul River on the first day, when it was atypically hot, albeit with a breeze, and we picked up the first Mongolian birds including Asian Azure-winged Magpie, White-cheeked Starling, a nice assortment of wildfowl and Demoiselle Crane. -

OMAN REPORT 2017 Final

The wonderful Grey Hypocolius was seen both in Oman and Bahrain (Hannu Jännes). OMAN 3-16/19 NOVEMBER 2017 LEADER: HANNU JÄNNES Birdquest’s tenth Oman & Bahrain tour proved yet again a success for many reasons. We recorded a respectable total of 238 taxa and 52 Birdquest ‘diamond’ species (regional specialities), saw some fantastic migrants and interesting seabirds. The highlight of this tour were perhaps Oman’s special owls species. Again we saw Omani Owl, a species only a handful of tour groups have seen before, and most of these were travelling with Birdquest! We also recorded the newly described Desert Owl, Pallid and Arabian Scops Owls, Little Owl, and ‘Arabian’ Spotted Eagle-Owl (a potential split from Spotted Eagle-Owl). You might not think a country comprising of mostly of rock and sand would be a great place for owls, but of the seven species sighted on this tour, three occupied the first, second and third place in the ‘Bird of the Trip’ vote! The mix of Middle Eastern specialities and sought-after migrants encountered on the tour, included Arabian Partridge, Persian Shearwater, Jouanin’s Petrel, Masked and Brown Booby, Red-billed Tropicbird, Verreaux’s Eagle, Crested Honey Buzzard, Red-knobbed Coot, Crab-plover, Long-toed Stint, Broad-billed Sandpiper, Sooty Gull; White-cheeked Tern, Spotted, Lichtenstein’s and Chestnut-bellied Sandgrouse, Oriental Turtle and African Collared Doves, Bruce’s Green Pigeon, Forbes-Watson’s Swift, Sooty Falcon, Steppe Grey Shrike, Fan-tailed Raven, Grey Hypocolius, Black-crowned Sparrow-Lark, White-spectacled Bulbul, Streaked Scrub Warbler, Plain Leaf and Green Warblers, Arabian Babbler, Asian Desert Warbler, Ménétries’s Warbler, Abyssinian White-eye, Tristram’s Starling, Blackstart, Hume’s, Variable, Red-tailed & Arabian Wheatears, Nile Valley, Palestine and Shining Sunbirds; Rüppell’s Weaver, Indian Silverbill, Yemen Serin, Arabian Golden-winged Grosbeak and Striolated Bunting. -

Asian Desert Warbler Sylvia Nana in Lava, West Bengal Del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D

182 Indian Birds VOL. 15 NO. 6 (PUBL. 15 JUNE 2020) collected by S. D. Ripley in Nagaland on 03 December 1950 (Yale Peabody Museum 2017), and the other (UMMZ birds #178643) collected by Walter Koelz in Karong, Manipur, on 23 November 1950 (University of Michigan Museum of Zoology 2019). A search of images posted on www.orientalbirdimages.org and specimens collected on portal.vertnet.org indicate that while dabryii has been recorded in China and Thailand, isolata has been recorded in Myanmar, and Meghalaya, Manipur, Nagaland, Chowdhury Roy Soumen and Mizoram in India. Therefore, it seems that during its winter/ seasonal movements, the distribution of dabryii may be limited to an area where it meets isolata: south of the Brahmaputra in India on the west, and Myanmar to the east. We could not trace any photographs of this race from India, and hence ours appears to be a first record after nearly 70 years from India. 235. Asian Desert Warbler showing clearly the yellow iris. Authors thank Praveen J. for his guidance and suggestions for this manuscript. The Asian Desert Warbler is a bird of the arid landscape, breeding through the northern and eastern regions of the Caspian Sea coasts, north-eastern Iran, much of Mongolia, and north- Reference western China. Its non-breeding range extends from north-eastern Rasmussen, P. C. & Anderton, J. C. (2012). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Vol. Africa, mostly along the Red Sea coast, Arabia, and farther eastwards 2. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions, Washington D. C. and Barcelona. till north-western India (Aymí et al. -

Kazakhstan & Uzbekistan April 24–May 16, 2019

KAZAKHSTAN & UZBEKISTAN BIRDING THE SILK ROAD OF CENTRAL ASIA APRIL 24–MAY 16, 2019 The scarcely distributed Saxaul Sparrow was a major highlight! Image by Cliff Hensel LEADER: MACHIEL VALKENBURG LIST COMPILED BY: MACHIEL VALKENBURG VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM KAZAKHSTAN & UZBEKISTAN April 24–May 16, 2019 By Machiel Valkenburg On a beautiful April afternoon in the Uzbekistan capital, a group of birders met up for a trip along the ancient Silk Road. Everybody has heard about the Silk Road, but the details of the region remain largely a mystery to most in America. Our trip to Central Asia took us along the highlights of the Uzbek city states of Samarqand and Bukhara while we visited the best birding spots in Kazakhstan. Spring was late in Central Asia this year, a good three weeks late! Yellow-breasted Azure Tit was easily found in Uzbekistan. Image by Cliff Hensel We started the tour in Samarqand where we indulged ourselves in the steep history of this gorgeous ancient city; the famous conqueror Timur made it the capital of his empire, and the richness of the town can be seen everywhere. We visited the most desired places for insight into their beauty and history. The Registan Square was especially admired by all as the best place of all. The friendliness of the local people was astonishing, and we took loads of selfies with all the local people visiting the sites. We were true rock stars! The food in Uzbekistan is fantastic, and we visited a plovchana, a restaurant serving only one dish, Plov! This is rice with lamb and raisins. -

UAE & Oman Trip Report

UAE & Oman Trip Report Arabian Birding Adventure th th 4 to 17 December 2014 (14 days) Grey Hypocolius by Forrest Rowland Tour Leaders: Forrest Rowland & Mark Beevers Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Forrest Rowland RBT UAE & Oman Trip Report 2014 2 Tour Intro There is nothing that quite compares to landing in Dubai. I’ve thought it must be something akin to what an astronaut might first perceive if he was to land on Mars, and find civilization there! The ships moving in the Gulf; sparkling lights line the shore; the Sun flashing against the World’s tallest building; so many sights standing out stark, and bizarre, against the barren natural setting. The United Arab Emirates, along with the Sultanate of Oman, exemplify and tout man’s ability to master the harshest of terrain. In the case of these two countries, this has been accomplished with a certain amount of grace that has gained the attention of the World. With constant change being the norm, new environmental standards in place, and one of the most ancient cultures in the entire industrial world, it was our privilege to enjoy these nations as our backdrop to one of the most unique birding adventures on Earth. Our route began in Dubai. We birded the metropolitan hotspots thoroughly, as well as a recently renowned farming operation in the far North, before heading southeast, inland, to “The Garden City” of Al Ayn. Crossing into Oman, we birded the Sohar Coast of the Indian Ocean, before heading high into the Hajars Mountains, the only place where snow is known to fall on the Arabian Peninsula! After a visit to Masirah Island on the central coast of Oman, we headed west and south through the vast expanse of the Rub Al Khali (the Empty Quarter). -

Status of Sylvia Warblers in Himachal Pradesh, India C

20 Indian BIRDS VOL. 16 NO. 1 (PUBL. 13 JULY 2020) Status of Sylvia warblers in Himachal Pradesh, India C. Abhinav & Ankit Vikrant Abhinav, C., & Vikrant, A., 2020. Status of Sylvia warblers in Himachal Pradesh, India. Indian BIRDS 16 (1): 20–25. C. Abhinav, Village & P.O. Ghurkari, Kangra 176001, Himachal Pradesh, India. E-mail: [email protected] [CA] [Corresponding author] Ankit Vikrant, Department of Space, Earth and Environment, Chalmers University of Technology, Maskingränd 2, 412 58 Gothenburg, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected] [AV] Manuscript received on 04 October 2019. imachal Pradesh is rich in avifauna due to the presence on 12 October 2016 at two different locations, a kilometer apart, of a diverse range of habitats. At one end of the state, in Nagrota Surian. One bird had a missing tail [1]. Both sites Hthere is the dry, cold desert of Trans-Himalaya in Spiti, and comprised scrubland predominated by drying plants of Senna at other end, there is Pong Lake, which is rich in avian diversity multiglandulosa. At one site there were a few bushes of Lantana and density. There is significant altitude variation in the state, camara, and a ziziphus sp. On 27 October 2016, at 1120 h, CA which provides suitable habitats for various birds. Six species of saw one individual at one of the previous sites. Sylvia warblers are found in India: Common Whitethroat Sylvia The Asian Desert Warbler has also been reported from other communis, Lesser Whitethroat S. curruca, Asian Desert Warbler parts of the state. CA saw one near Kahan, along the Kumarhatti- S. -

Our Tour Began in Arusha, the Safari Capital of Tanzania, from Where We

Mongolia Birding The Gobi and Beyond Trip Report 24th May to 11th June 2014 Henderson's Ground Jay by David Erterius Trip Report – RBT Mongolia 2014 2 Tour Intro: Imagine a territory half as large as Europe but with only three million inhabitants, characterized by vast and mesmerizing natural beauty, and nomadic people making a living from their livestock on seemingly infinite wind-swept plains... Cornered between Russia and China, Mongolia, also known as “the land of the eternal blue sky”, sits on a high plateau at an average altitude of 1500 metres, far from any ocean or sea. It’s the second largest landlocked country after Kazakhstan, and since the end of the communist era in 1990, visitors have experienced a secure and stable environment with well- established democratic institutions, making Mongolia a paradise for both business and leisure. In recent years the country has also experienced strong economic growth, which is directly reflected in the tourism industry. Just a decade ago, countryside tourist camps with good accommodation were almost non-existent – unlike today. Furthermore, Mongolia is situated within an ecological transition zone, where the forests of Siberia merge south into the Central Asian desert and steppe landscapes. This The old and the new: Shepherd on motorbike by David Erterius makes the countryside unique, with a distinctive and remarkable flora and fauna. The north consists of vast expanses of lush taiga and beautiful valleys surrounded by spectacular rock formations and green meadows. The central parts are characterized by endless green steppes with nomads living in their yurts surrounded by their huge cattle herds, as well as the enchanting and rarely visited Khangay Mountains with its sub-alpine and alpine habitats, verdant forests and breathtaking scenery.