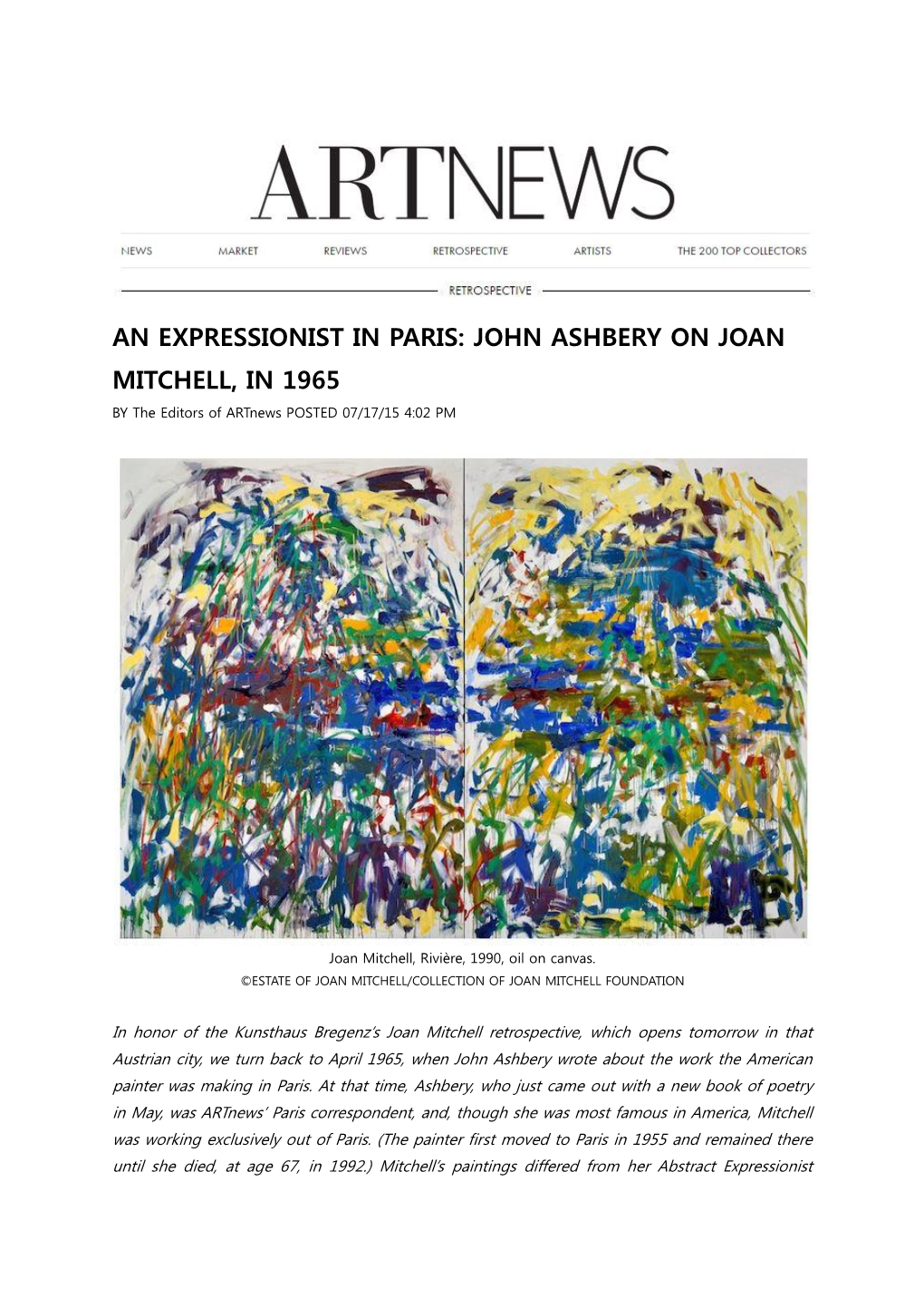

AN EXPRESSIONIST in PARIS: JOHN ASHBERY on JOAN MITCHELL, in 1965 by the Editors of Artnews POSTED 07/17/15 4:02 PM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spotlight on Shawne Major

EXHIBITION ANNOUNCEMENT Hilliard University Art Museum University of Louisiana at Lafayette 710 East Saint Mary Blvd. Lafayette, LA 70503 Laura Blereau, Curator [email protected] (337) 482-0823 Spotlight on Shawne Major Exhibition Dates: Dec 9, 2016 – May 13, 2017 Reception: 6:00-8:00 PM, Friday, Feb 3, 2017 Artist Talk: 6:00 PM, Wednesday, March 6, 2017 The Hilliard University Art Museum is pleased to announce Spotlight on Shawne Major. This display on the museum’s second floor features three large scale works by the Opelousas-based artist: Bud Sport (2008), Nadir (2011) and Vestige (2001). Her mixed-media assemblage work is also represented in the concurrent exhibition Spiritual Journeys: Homemade Art from the Becky and Wyatt Collins Collection. Biography Shawne Major was born in New Iberia in 1968. She earned a BFA in painting in 1991 from the University of Southwestern Louisiana Shawne Major. Nadir, 2011 (now known as the University of Louisiana at Lafayette). In 1995, © Shawne Major she also earned an MFA in sculpture from the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. The recipient of many awards, Major has been recognized with many residencies including the Hermitage Artist Retreat in Englewood, Florida (2017); Joan Mitchell Center in New Orleans, LA (2016); Robert Rauschenberg Foundation in Captiva Island, FL (2015); Art Omi in Ghent, NY (2009); Sculpture Space in Utica, NY (1997); Corporation of Yaddo in Saratoga Springs, NY (1995); and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine (1992). She has also received fellowships and grants from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation (2008) and the Dieu Donne Papermill in New York (1996). -

Creating a Living Legacy Program for Visual Artists

CALL CREATING A LIVING LEGACY PROGRAM FOR VISUAL ARTISTS Career Documentation for the Visual Artist: An Archive Planning Workbook and Resource Guide Getting artwork ready for sorting Neal Ambrose-Smith CALL CREATING A LIVING LEGACY Table of Contents An Introduction to the Workbook 1 » CHAPTER 1 Importance of Documenting and Archiving Your Work 3 » CHAPTER 2 Getting Started and Setting Goals 9 Setting Manageable Goals 10 Chapter 2 Worksheet 11 » CHAPTER 3 Getting Assistance 15 » CHAPTER 4 The Legacy Specialist 19 Getting Started with a Legacy Specialist 21 Chapter 4 Worksheet 22 Chapter 4 Worksheet 23 » CHAPTER 5 The Physical Inventory 25 Steps for Organizing and Taking Care of Your Physical Inventory 26 Resources 29 Chapter 5 Worksheet 30 » CHAPTER 6 The Record-Keeping System 33 Spreadsheets and Databases 35 Information Your Records Should Contain 37 Artwork Record 37 Unique inventory number 37 Contact Record 40 Exhibition Record 40 Archive Record 41 Resources 42 » CHAPTER 7 Photographing Your Work 45 Resources 46 » CHAPTER 8 Budgeting 47 Chapter 8 Worksheet 49 A Final Note 50 Bios 51 Glossary 52 Overloaded storage shed Neal Ambrose-Smith CALL CREATING A LIVING LEGACY An Introduction to the Workbook This workbook was created to help an artist, artist’s assistant, Legacy Specialist, family member, or friend of an artist in the process of career documentation FOR ARTISTS: This workbook will help you to: » assess what you have or have not archived » develop and/or improve on an inventory and archiving system » set realistic archiving goals -

Bma to Open Major Retrospective on Artist Joan Mitchell in March 2022

BMA TO OPEN MAJOR RETROSPECTIVE ON ARTIST JOAN MITCHELL IN MARCH 2022 Co-Organized by BMA and SFMOMA, Joan Mitchell Offers New Scholarship on Mitchell’s Vision, History, and Artistic Process BALTIMORE, MD (UPDATED March 1, 2021)—Joan Mitchell has long been hailed as a formidable creative force—a woman artist who attained critical acclaim and success in the male- dominated art circles of the 1950s, and then went on to make her own distinctive way in the world for four decades. From March 6 through August 14, 2022, The Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) will present a comprehensive survey of Mitchell’s oeuvre that establishes a new depth of scholarship on her work. Titled Joan Mitchell, the retrospective will feature approximately 60 works, including rarely seen early paintings and drawings, the vibrant gestural compositions that established her career, and large-scale, colorful, multi-panel masterpieces from her later years. With suites of major paintings as well as sketchbooks, charcoal drawings, and pastels on paper, the exhibition will open a new window into the richness of Mitchell’s practice and present a model of art history that accommodates multiple chapters and evolving styles. Joan Mitchell is accompanied by a catalogue that will provide further essential insight into Mitchell’s artistic achievements and the inspirations that drove them. Co-organized by the BMA and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), the exhibition is grounded in more than two years of archival research and an extensive firsthand review of Mitchell’s works conducted by co-curators Katy Siegel, BMA Senior Programming & Research Curator and Thaw Chair of Modern Art at Stony Brook University, and Sarah Roberts, Andrew W. -

Press Review

Press SUN WOMEN Louise Bourgeois Helen Frankenthaler Eva Hesse Jacqueline Humphries Lee Krasner Joan Mitchell Louise Nevelson Curated by Jérôme Neutres April 24 – June 29 2019 Whitewall , June 27, 2019 “SUN WOMEN” Pays Tribute to the Artists Who Fought for Equal Acknowledgment By Pearl Fontaine At the Charles Riva Collection in Brussels, curator Jérômre Neutres has conceived an exhibition of works by seven artists, entitled “SUN WOMEN.” Named for Lee Krasner’s series “The Sun Woman,” the exhibition features a group of artists whose works are, today, known to be part of the women’s emancipation movement of the 20th century. “I feel totally female. I didn’t compete with men and I don’t want to look like a man!” said Louise Nevelson. Not to be categorized because of gender, the artists on view—including Krasner, Nevelson, Louise Bourgeoise, Helen Frankenthaler, Eva Hesse, Jacqueline Humphries, and Joan Mitchell— sought to obtain equal acknowledgment as their male counterparts. Great masters throughout the ages were never referred to as “da Vinci, the male artist,” or “Hemingway, the male writer,” so neither should female creators be referred to as such. Instead of essentializing the work of these women, the exhibition presents them as artists neglected in a scene that has always favored males. A recurring theme of abstraction runs amongst each artist’s style—something which Eric de Chassey suggests is to be expected, since abstraction is “a liberation, the triumph of artistic freedom as a possibility, unhindered by external references.” By committing to an abstracted practice, these artists were essentially pledging themselves to defying the norms (social, sexual, political, and psychological) of their times, where women were held to standards of domesticated delicacy. -

Joan Mitchell

Joan Mitchell Bleibtreustraße 45, Berlin-Charlottenburg 10 November 2013 – 18 January 2014 Opening: 10 November, 11 am-5 pm Untitled, 1951 Oil on canvas 80 x 70 in / 203.2 x 177.8 cm © Estate of Joan Mitchell Galerie Max Hetzler is pleased to present an exhibition by Joan Mitchell in Bleibtreustraße 45, Berlin-Charlottenburg from November 10, 2013 until January 18, 2014. For the first time in Berlin, an exceptional ensemble of paintings and pastels from the almost 50 years of the artist's career will be featured. One of the most respected figures of Abstract Expressionism, Joan Mitchell (1925-1992) came to an early attention with her lyrical abstract paintings. In 1951, at the age of 26, she participated in the Ninth Street Art Exhibition in New York, alongside Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Clyfford Still, Mark Rothko, Franz Kline, Philip Guston and Helen Frankenthaler, among others. In 1955, she began dividing her time between New York and Paris. She maintained close relation- ships with many New York School painters and poets even after 1968, when she settled in Vétheuil, a small town in the countryside outside of Paris. She worked there continuously until her death in 1992. Mitchell’s commitment to the tenets of gestural abstraction remained firm and uncompromising during all her life, as to be seen in the paint- ings from the exhibition. A dense and striking composition cha- racterizes the early Untitled painting from 1951 (see fig.), while the Untitled painting from 1958 (see fig.) depicts a more tempestuous and expressive surface, whereas Le chemin des écoliers, 1960, betrays the inspiration from the French landscapes. -

JOAN MITCHELL, Minnesota

JOAN MITCHELL, Minnesota 1980, oil on canvas (four panels) 102 1/2 x 243 inches Joan Mitchell Her work & Minnesota Joan Mitchell & Poetry Autumn by Joan Mitchell Joan Mitchell was born in Chicago When asked about her work, Joan Mitchell said: “My This poster was produced in conjunction with an exhibition The rusty leaves crunch and crackle, in 1925 and earned a BFA from the paintings repeat a feeling about Lake Michigan, or of Joan Mitchell’s work at the Poetry Foundation in Chicago, Blue haze hangs from the dimmed sky, which explored her relationship with poetry. Mitchell’s mother Art Institute of Chicago in 1947. In water, or fields…it’s more like a poem, and that’s what The fields are matted with sun-tanned stalks — the early 1950s she participated in I want to paint.” Through abstraction, Mitchell lyrically (a fiction writer, editor, and poet) was an associate editor at Wind rushes by. the vibrant downtown New York art conferred feeling onto landscape, uniting elements Poetry magazine from 1920 to 1925 and remained affiliated scene and spent time with many other of visual observation and physical experience with with the magazine for more than forty-five years. Because of The last red berries hang from the thorn-tree, painters and poets. It was during this an emotional state of mind. She painted Minnesota, her mother’s involvement in literary circles – and her love of time in New York that she began to an expansive work on four panels, in 1980. The use language and poetry – Mitchell grew up in a home filled with The last red leaves fall to the ground. -

Widening Circles | Photographs by Reginald Eldridge, Jr

JOAN MITCHELL FOUNDATION MITCHELL JOAN WIDENING CIRCLES CIRCLES WIDENING | PHOTOGRAPHS REGINALD BY ELDRIDGE, JR. Widening Circles Portraits from the Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist Community at 25 Years PHOTOGRAPHS BY REGINALD ELDRIDGE, JR. Sonya Kelliher-Combs Shervone Neckles Widening Circles Portraits from the Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist Community at 25 Years PHOTOGRAPHS BY REGINALD ELDRIDGE, JR. Widening Circles: Portraits from the Joan Mitchell Foundation Artist Community at 25 Years © 2018 Joan Mitchell Foundation Cover image: Joan Mitchell, Faded Air II, 1985 Oil on canvas, 102 x 102 in. (259.08 x 259.08 cm) Private collection, © Estate of Joan Mitchell Published on the occasion of the exhibition of the same name at the Joan Mitchell Foundation in New York, December 6, 2018–May 31, 2019 Catalog designed by Melissa Dean, edited by Jenny Gill, with production support by Janice Teran All photos © 2018 Reginald Eldridge, Jr., excluding pages 5 and 7 All artwork pictured is © of the artist Andrea Chung I live my life in widening circles that reach out across the world. I may not complete this last one but I give myself to it. – RAINER MARIA RILKE Throughout her life, poetry was an important source of inspiration and solace to Joan Mitchell. Her mother was a poet, as were many close friends. We know from well-worn books in Mitchell’s library that Rilke was a favorite. Looking at the artist portraits and stories that follow in this book, we at the Foundation also turned to Rilke, a poet known for his letters of advice to a young artist. -

Joan Mitchell Retrospective. Her Life and Paintings 18 | 07 – 25 | 10 | 2015

KUB 2015.03 | Press release Joan Mitchell Retrospective. Her Life and Paintings 18 | 07 – 25 | 10 | 2015 Curators of the exhibition Yilmaz Dziewior and Rudolf Sagmeister Press Conference Thursday, July 16, 2015, 11 a.m. Opening Friday, July 17, 2015, 6 p.m. Press photos per download www.kunsthaus-bregenz.at Together with the Museum Ludwig in Cologne and in cooperation with the Joan Mitchell Foundation in New York, Kunsthaus Bregenz is presenting a large-scale survey exhibition of the legendary artist Joan Mitchell (1925 1992). The show’s focus is on painting, ranging from the early work of the 1950s to her last years, presenting nearly thirty paintings by one of 20th century art’s most significant protagonists. A large part of the exhibition is dedicated to the first Extensive public presentation of archival materials, provi- ding an extraordinary insight into the artist’s fascinating life. Film, photographs, and other ephemera shed light on Joan Mitchell’s personality and her relationship to such cultural figures as Elaine de Kooning, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Frank O’Hara, and Samuel Beckett. Vorarlberg architect Bernardo Bader has developed a display for these archival materials, enabling them to enter into a compelling dia- logue with the artist’s works. In 1959 Joan Mitchell participated in documenta II, and her work is in the collections of important museums in the USA and France. In recent years a younger generation of artists has rediscovered her work. This renewed dialogue has been largely due to her emancipated attitudes and the uni- que position her painting enjoys, located between the USA and Europe. -

Women of Abstract Expressionism

WOMEN OF ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM EDITED BY JOAN MARTER INTRODUCTION BY GWEN F. CHANZIT, EXHIBITION CURATOR DENVER ART MUSEUM IN ASSOCIATION WITH YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW HAVEN AND LONDON Published on the occasion of the exh1b1t1on Women of Abstract Denver Art Museum Expressionism. organized by the Denver Art Museum Director of Publications: Laura Caruso Curatorial Assistant: Renee B. Miller Denver Art Museum. June-September 2016 Yale University Press Mint Museum. Charlotte. North Carolina. October-January 2017 Palm Springs Art Museum. February-May 2017 Publisher. Art and Architecture: Patricia Fidler Editor Art and Architecture: Katherine Boller Wh itechapel Gallery. London.June-September 2017 . Production Manager: Mary Mayer Women of Abstract Expressionism is organized by the Denver Art Museum. It is generously funded by Merle Chambers: the Henry Luce Designed by Rita Jules. Miko McGinty Inc. Foundation: the National Endowment for the Arts: the Ponzio family: Set in Benton Sans type by Tina Henderson DAM U.S. Bank: Christie's: Barbara Bridges: Contemporaries. a Printed in China through Oceanic Graphic International. Inc. support group of the Denver Art Museum: the Joan Mitchell Foundation: the Dedalus Foundation: Bette MacDonald: the Deborah Library of Congress• Control Number: 2015948690 Remington Charitable Trust for the Visual Arts;the donors to the ISBN 978-0-300-20842-9 (hardcover): 978-0914738-62-6 Annual Fund Leadership Campaign: and the citizens who support the (paperback) Scientific and Cultural Facilities District (SCFD). We regret the A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. omission of sponsors confirmed after February 15. 2016. This paper meets the requirements of ANS1m1so 239.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

JOAN MITCHELL, Beauvais

JOAN MITCHELL, Beauvais 1986, oil on canvas diptych 110 1/4 x 157 1/2 inches Joan Mitchell Her work & Beauvais Joan Mitchell was born in Joan Mitchell’s artworks communicate, through color and gesture, the feelings and Chicago in 1925 and earned a memories of people, places and things in her life that were important to her. She said, BFA from the Art Institute of “My paintings repeat a feeling abut Lake Michigan, or water, or fields...it’s more like a Chicago in 1947. In the early poem...and that’s what I want to paint.” The myriad things that comprised and moved 1950’s she participated in the within her landscapes - water, sky, trees, flowers, dogs - created images and memories that vibrant downtown New York art all went into her paintings. scene and spent time with many Beauvais, titled after a town north of Paris that has a well-known gothic cathedral, is a other painters and poets. It was large painting that evokes a vivid landscape with an expansive sense of space. White during this time in New York brushstrokes around the edges of each panel, mingled with a bright, soft yellow, create an that she began to paint in a way atmospheric sensation of weather, water and sky permeated with light. known as abstract expressionism. The paint in Beauvais suggests In 1955, she moved to the city of Lake Michigan, 1946. Photo Barney Rosset matter in flux between Paris, France and in 1967, from physical states. Oranges, the city to a house in a small town near Paris called Vétheuil. -

Creating a Living Legacy

Joan Mitchell at her home in Vétheuil, France, 1984. Photo by Édouard Boubat. CREATING A LIVING LEGACY CALL CREATING A LIVING LEGACY Estate Planning Workbook for Visual Artists Contents Acknowledgments . 2 Introduction . .7 Your Legacy . .8 Legacy Vehicles . 13 The Basics . 16 Your Team . 19 Your Estate . .21 Estate Planning Questions for the Artist . .26 Estate Planning Questions for the Artist on Copyright. .32 Talking With an Estate Planning Attorney . 33 Other Resources . .34 Workbook Contributors . 35 This resource was originally published in 2012, and reprinted in 2019 with minor revisions. 1 CALL CREATING A LIVING LEGACY Acknowledgments SPECIAL THANKS The Joan Mitchell Foundation would like to acknowledge and The Arts & Business Council of Greater Boston/Volunteer thank our Board of Directors for their invaluable support and Lawyers for the Arts of Massachusetts would like to thank: contributions to the development of the Creating a Living » The Joan Mitchell Foundation for its leadership and Legacy Estate Planning Workbook. support. Joan Mitchell Foundation Board of Directors » The many organizations and individuals that have » Alejandro Anreus, Ph.D., President worked with care, determination, and impact to support the creative community and keep the issue of estate » Tomie Arai, Vice-President planning and legacy planning for artists alive. We are » Theodore S. Berger, Treasurer honored to continue the conversation and contribute to » Ronald Bechet their valuable work. » Dan Bergman » Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts programs around the country for their service and extraordinary efforts to » Tyrone Mitchell provide assistance to their constituencies. » Yolanda Shashaty » Fay Chandler for supporting our efforts to educate » Michele Tortorelli artists on estate and legacy planning since 2006. -

Excerpted From

Excerpted from © Whitney Museum of American Art. All rights reserved. May not be copied or reused without express written permission of the Whitney Museum of American Art. click here to BUY THIS BOOK Rage, violence, and anger have often been deployed as heuristic keys in interpreting the work of Joan Mitchell, especially the early work. In her catalogue of a major retrospective of Mitchell’s work, Judith Bernstock tied Mitchell’s painting To the Harbor- master to the Frank O’Hara poem from which Mitchell derived her title by referring explicitly to the lines in which water appears as the traditional symbol of chaos, creation, and destruction. Taking Joan account of Gaston Bachelard’s theory that “violent water tradi- tionally appears as male and malevolent and is given the psycho- logical features of anger in poetry,” Bernstock went on to maintain that both Mitchell’s “frenzied painting” and O’Hara’s poem “evoke Mitchell a fearful water with invincible form (‘metallic coils’ and ‘terrible channels’) and voice-like anger, a destructive force threatening internal and external chaos.” She concluded with a reference to the formal elements in the painting that evoke the menacing mood of the poem: “the cacophonous frenzy of short, criss-crossing strokes A Rage of intense color . the agitation heightened as lyrical arm-long sweeps across the top of the canvas press down forcefully, even oppressively, on the ceaseless turbulence below.” Of Rock Bottom, a work of –, Mitchell herself maintained: “It’s a very vio- to Paint lent painting,