Does Manly Courage Exist?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Trap Pilates POPUP

TRAP PILATES …Everything is Love "The Carters" June 2018 POP UP… Shhh I Do Trap Pilates DeJa- Vu INTR0 Beyonce & JayZ SUMMER Roll Ups….( Pelvic Curl | HipLifts) (Shoulder Bridge | Leg Lifts) The Carters APESHIT On Back..arms above head...lift up lifting right leg up lower slowly then lift left leg..alternating SLOWLY The Carters Into (ROWING) Fingers laced together going Side to Side then arms to ceiling REPEAT BOSS Scissors into Circles The Carters 713 Starting w/ Plank on hands…knee taps then lift booty & then Inhale all the way forward to your tippy toes The Carters exhale booty toward the ceiling….then keep booty up…TWERK shake booty Drunk in Love Lit & Wasted Beyonce & Jayz Crazy in Love Hands behind head...Lift Shoulders extend legs out and back into crunches then to the ceiling into Beyonce & JayZ crunches BLACK EFFECT Double Leg lifts The Carters FRIENDS Plank dips The Carters Top Off U Dance Jay Z, Beyonce, Future, DJ Khalid Upgrade You Squats....($$$MOVES) Beyonce & Jay-Z Legs apart feet plie out back straight squat down and up then pulses then lift and hold then lower lift heel one at a time then into frogy jumps keeping legs wide and touch floor with hands and jump back to top NICE DJ Bow into Legs Plie out Heel Raises The Carters 03'Bonnie & Clyde On all 4 toes (Push Up Prep Position) into Shoulder U Dance Beyonce & JayZ Repeat HEARD ABOUT US On Back then bend knees feet into mat...Hip lifts keeping booty off the mat..into doubles The Cartersl then walk feet ..out out in in.. -

Prospector Volume 106 Edition 5 February 27, 2014

Carroll College Student Newspaper The Helena, Montana Prospector Volume 106 Edition 5 February 27, 2014 Academic integrity Proposals for new activities survey finds center to be presented to board positive results for Carroll students Emily Dean BBeefforee ASCC President The Academic Integrity Committee recently conducted an institution-wide student/faculty survey regarding academ- ic integrity on campus. The survey was administered by Rutgers University and the Center for Academic Integrity on 10 other campuses nationwide. Carroll¶s results were a positive reÀec- tion of the student body and its opinions on the importance of academic integrity. The survey found 30 percent of the stu- dent population and 70 percent of faculty completed the survey. The Committee received the results of the survey in January and found Carroll’s results to be within 10 percent of the averages of the other institutions surveyed. Carroll stu- Above is Dowling Studio Architect's proposal for the new student activities center. This is just one of three proposals dents indicated “medium/high levels” of the Board of Trustees will have to choose from on Feb. 28. View the back page to see the other proposals. understanding and support of the school’s Photo courtesy of Dowling Studio Architects and Carroll College academic integrity policy. According to the Committee, these statistics mean our Nate Kavanagh library and PE Center, attaching it to the According to McCarvel, fundraising policy is effective, even more so than library, and attaching it to the current PE for the new center would start with the other institutions surveyed. Co-Editor Center. -

Most Requested Songs of 2016

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2016 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Ronson, Mark Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 4 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 5 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 6 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 7 Swift, Taylor Shake It Off 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 10 Sheeran, Ed Thinking Out Loud 11 Williams, Pharrell Happy 12 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 13 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 14 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 15 Mars, Bruno Marry You 16 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 17 Maroon 5 Sugar 18 Isley Brothers Shout 19 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 20 B-52's Love Shack 21 Outkast Hey Ya! 22 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 23 Legend, John All Of Me 24 DJ Snake Feat. Lil Jon Turn Down For What 25 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 26 Timberlake, Justin Can't Stop The Feeling! 27 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 28 Beatles Twist And Shout 29 Earth, Wind & Fire September 30 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 31 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 32 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 33 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 34 Spice Girls Wannabe 35 Temptations My Girl 36 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 37 Silento Watch Me 38 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 39 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 40 Jordan, Montell This Is How We Do It 41 Sister Sledge We Are Family 42 Weeknd Can't Feel My Face 43 Dnce Cake By The Ocean 44 Flo Rida My House 45 Lmfao Feat. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Band Song-List

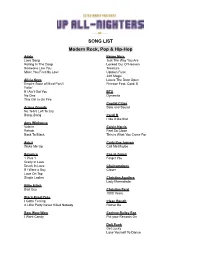

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

Mediamonkey Filelist

MediaMonkey Filelist Track # Artist Title Length Album Year Genre Rating Bitrate Media # Local 1 Kirk Franklin Just For Me 5:11 2019 Gospel 182 Disk Local 2 Kanye West I Love It (Clean) 2:11 2019 Rap 4 128 Disk Closer To My Local 3 Drake 5:14 2014 Rap 3 128 Dreams (Clean) Disk Nellie Tager Local 4 If I Back It Up 3:49 2018 Soul 3 172 Travis Disk Local 5 Ariana Grande The Way 3:56 The Way 1 2013 RnB 2 190 Disk Drop City Yacht Crickets (Remix Local 6 5:16 T.I. Remix (Intro 2013 Rap 128 Club Intro - Clean) Disk In The Lonely I'm Not the Only Local 7 Sam Smith 3:59 Hour (Deluxe 5 2014 Pop 190 One Disk Version) Block Brochure: In This Thang Local 8 E40 3:09 Welcome to the 16 2012 Rap 128 Breh Disk Soil 1, 2 & 3 They Don't Local 9 Rico Love 4:55 1 2014 Rap 182 Know Disk Return Of The Local 10 Mann 3:34 Buzzin' 2011 Rap 3 128 Macc (Remix) Disk Local 11 Trey Songz Unusal 4:00 Chapter V 2012 RnB 128 Disk Sensual Local 12 Snoop Dogg Seduction 5:07 BlissMix 7 2012 Rap 0 201 Disk (BlissMix) Same Damn Local 13 Future Time (Clean 4:49 Pluto 11 2012 Rap 128 Disk Remix) Sun Come Up Local 14 Glasses Malone 3:20 Beach Cruiser 2011 Rap 128 (Clean) Disk I'm On One We the Best Local 15 DJ Khaled 4:59 2 2011 Rap 5 128 (Clean) Forever Disk Local 16 Tessellated Searchin' 2:29 2017 Jazz 2 173 Disk Rahsaan 6 AM (Clean Local 17 3:29 Bleuphoria 2813 2011 RnB 128 Patterson Remix) Disk I Luh Ya Papi Local 18 Jennifer Lopez 2:57 1 2014 Rap 193 (Remix) Disk Local 19 Mary Mary Go Get It 2:24 Go Get It 1 2012 Gospel 4 128 Disk LOVE? [The Local 20 Jennifer Lopez On the -

Arts-Based Research in Psychiatry: a Way to the Examination of the Popular Beliefs About Mental Disorders

Arts-based research in Psychiatry: A way to the examination of the popular beliefs about mental disorders Fabián Pavez1,2 EPA Virtual 2021. 29th European Congress of Psychiatry. 10-13 April 2021 Research about the depictions of psychiatry and mental disorders in popular culture has been scarce and often lacks systematized research strategies1. However, this tendency has changed in the last few years and it is now possible to find articles that investigate the social representations of References mental illness through the analysis of the media, such as newspapers and social media2,3 and the 4-11 products of popular culture, such as music, films, literature, and other artistic manifestations . The 1. Pavez F, Saura E, Pérez G, Marset P. Social Representations of Psychiatry and Mental Disorders Examined Through the Analysis of Music inclusion of the MeSH term 'Medicine in the Arts' in the database of the U.S. National Library of as a Cultural Product. Music Med 2017;9(4):247–53. 2. Robinson P, Turk D, Jilka S, Cella M. Measuring attitudes towards mental health using social media : investigating stigma and trivialisation. Medicine in 2018 is possibly indicative of the emerging relevance of this topic. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2018. Available in: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1571-5 3. Joseph A, Tandon N, Yang L, Duckworth K, Torous J, Seidman L, et al. #Schizophrenia: Use and misuse on Twitter. Schizophr Res 2015;165:111–5. 4. Pirkis J, Blood R, Francis C, McCallum K. On-Screen Portrayals of Mental Illness: Extent, Nature, and Impacts. J Health Commun 2006; The study of the products of popular culture can give us information about common ideas present in 11(5):523-41. -

Cultural Differences in Tweeting About Drinking Across the US

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Cultural Differences in Tweeting about Drinking Across the US Salvatore Giorgi 1,2 , David B. Yaden 3, Johannes C. Eichstaedt 4 , Robert D. Ashford 5, Anneke E.K. Buffone 3, H. Andrew Schwartz 6, Lyle H. Ungar 1 and Brenda Curtis 2,* 1 Computer and Information Science Department, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; [email protected] (S.G.); [email protected] (L.H.U.) 2 National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA 3 Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; [email protected] (D.B.Y.); buff[email protected] (A.E.K.B.) 4 Department of Psychology & Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA; [email protected] 5 Substance Use Disorders Institute, University of the Sciences, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; [email protected] 6 Department of Computer Science, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 January 2020; Accepted: 8 February 2020; Published: 11 February 2020 Abstract: Excessive alcohol use in the US contributes to over 88,000 deaths per year and costs over $250 billion annually. While previous studies have shown that excessive alcohol use can be detected from general patterns of social media engagement, we characterized how drinking-specific language varies across regions and cultures in the US. From a database of 38 billion public tweets, we selected those mentioning “drunk”, found the words and phrases distinctive of drinking posts, and then clustered these into topics and sets of semantically related words. -

Live Exchange Party Band Song List

Live Exchange Party Band Song List FUNK Uptown Funk-Bruno Mars Let's groove-EWF September-EWF Before I let go-maze I'll be around- Spinners That's the way- KC in the sunshine band Brick House- commodores Jamaica Funk-Tom Browne Da Butt- EU Ain't nobody- Chaka Khan Tell Me something good- Chaka Khan Candy- cameo Boogie Shoes-KC and the sunshine band Ladies night- Kool and the Gang Boogie Oogie- A taste of Honey Play that funky music- wild Cherry Superstition-Stevie Wonder Sign sealed delivered- Stevie Wonder Best of my Love-The Emotions To be real-Cheryl Lynn Funky town- Lipps INC Funky good time- James Brown Get up-James Brown I feel good-James Brown Bird- Morris Day and the Time Get down on it- Kool and the gang Drop The bomb- The Gap Band Give it to me Baby- Rick James Word up-Cameo Jungle love The bird Teena Marie - Square Biz Gap Band - Early in the morning Midnight Star - No parking on the dance Floor MJ - Dancing Machine Morris Day - Jungle Love RAP Snap your fingers-Lil John About the money- T.I. All I do is win- Dj Alright- Kendrick Lamar Summertime- Dj Jazzy Jeff & the fresh Prince Whip and Nae Nae-Silentó Hotline Bling- Drake California- Ricco Barrino Better have my money-Rihanna Hey ya- Outkast R&B Love Changes- mothers finest Tyrone-Erykah Badu On&On-Erykah Badu Just Friends-Musiq The way-Jill Scott He loves me-Jill Scott Between the sheets-Isley Brothers Foot steps in the dark-Isley Brothers Sweet thing-Chaka Khan Stay with me- Sam Smith All of Me- John legend Do for love- Bobby Caldwell Just the two of us-Bill Withers Dock