Managing Eritrean Shipping Agency Services for Improved Results Weldegiorgis Weldegebriel Kibrom World Maritime University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RMS Medina First World War Site Report

Forgotten Wrecks of the RMS Medina First World War Site Report 2018 FORGOTTEN WRECKS OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR RMS MEDINA SITE REPORT Maritime Archaeology Trust: Forgotten Wrecks of the First World War Site Report: RMS Medina (2018) Table of Contents i Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................ 3 ii Copyright Statement ........................................................................................................................ 3 iii List of Figures .................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Project Background ............................................................................................................................. 4 2. Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Desk Based Historic Research ....................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Associated Artefacts ..................................................................................................................... 5 3. Vessel Biography: RMS Medina .......................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Vessel Type and Build .................................................................................................................. -

Aaa800ews0p1260outi0june0

Report No. AAA80 - DJ Republic of Djibouti Public Disclosure Authorized Study on regulation of private operators in the port of Djibouti Technical Assistance Final report June 2012 Middle East and North Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized Transport Group World Bank document Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Study on regulation of private operators in the port of Djibouti Contents CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 8 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 9 REGULATION ACTION PLAN FOR PORT ACTIVITES IN DJIBOUTI ........................................ 13 REPORT 1 - DIAGNOSIS ................................................................................................................. 16 1. PORT FACILITIES AND OPERATORS ................................................................................. 17 1.1. An outstanding port and logistics hub .......................................................... 17 1.2. Doraleh oil terminal ...................................................................................... 18 1.3. Doraleh container terminal ........................................................................... 18 1.4. Djibouti container terminal ........................................................................... 19 1.5. Djibouti bulk terminal .................................................................................. -

![(The “Zagora”) QBD (Comm Ct) [2016] EWHC 3212](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0034/the-zagora-qbd-comm-ct-2016-ewhc-3212-480034.webp)

(The “Zagora”) QBD (Comm Ct) [2016] EWHC 3212

Oldendorff GmbH & Co KG -v- Sea Powerful II Special Maritime Enterprises and Others (The “Zagora”) QBD (Comm Ct) [2016] EWHC 3212 In circumstances where original bills of lading are not available at the discharge port, it is still common commercial practice for the cargo to be discharged to the receiver against a letter of indemnity (“LOI”) conditional on delivery of the cargo to the receiver named in the LOI. The matter can be more complex where agents are involved within a chain of LOIs. The English High Court recently considered an action pertaining to a chain of LOIs where the claimants argued that the LOI was not enforceable as the cargo was not delivered to the nominated receiver. The question that the Court had to consider was whether in the above circumstances the party that did in fact take delivery of the cargo from the ship did so as agent on behalf of Owners or on behalf of the party identified in the LOI to take delivery. Facts The matter concerned a cargo of iron ore carried on board the M/V “ZAGORA” on a voyage from Koolan Island in Western Australia to Lanshan in China. SCIT Trading Ltd (“SCIT Trading”) agreed to sell 70,000 mt of iron ore on CFR terms to Xiamen C & D Minerals Co Ltd (“Xiamen”). Clause 9 of the sale contract provided that the agent at the discharge port be appointed by the buyer, Xiamen. Xiamen subsequently agreed to sell the cargo to an associated company, Cheongfuli Company Ltd, who in turn agreed to sell the cargo to Shanxi Haixin International Iron and Steel Co. -

The Mariners Guide to Glensanda

Glensanda Port & Terminal Information Booklet THE MARINERS’ GUIDE TO GLENSANDA – PORT INFORMATION Welcome to the Port of Glensanda. The following information is intended to help ensure that all activities carried out here are done safely, and with a regard to the environment. All operations are carried out in compliance with the Port Marine Safety Code and with the Glensanda Harbour Byelaws. Please read the following information and take note of those sections that apply to you. If you have any questions regarding any aspect of the Glensanda operation, please do not hesitate to contact me. Ian F.Henry Issue 15 Glensanda Harbour Master 5th February 1st February 2019 2019 Port Authority Aggregate Industries UK Ltd. Rhugh Garbh Depot Barcaldine Nr Oban Argyll PA37 1SE IMO Port Locode : GB GSA Facility No. 0001 Harbour Master / PFSO Ian F.Henry Glensanda Office Tel: 01631 568110 / 568100 Fax: 01631 730460 Home Tel: 01631 565572 Mobile: 07815 966302 e-mail: [email protected] Pilot Duty Pilot Office Tel: 01631 568116 / 730537 Fax: 01631 730460 e-mail : [email protected] Shipping Agency Morvern Shipping Agency Ltd. Tel: 01631 568110 / 568100 Fax: 01631 730460 e-mail : [email protected] Loading Crew Shift Manager Manger of berthing / loading crew Tel: 01631 568101 / 568130 Mobile (24 hrs) 07815 966358 e-mail : [email protected] See company website for more information on Glensanda – www.aggregate.com 2 THE MARINERS’ GUIDE TO GLENSANDA – PORT INFORMATION General Information Glensanda Ship One berth only – in regular use by ships of between 100 and 110,000 Loading Jetty m/t deadweight. -

Maritime Directory of Shipping Services 2018

Maritime Directory of Shipping Services 2018 lloydslist.com Lloyd’s List Maritime Directory of Shipping Services 2018 Introduction & Contents Welcome to the 2018 edition of the Lloyd’s List Maritime Directory of Shipping Services. This latest edition incorporates advertised services from industry leading companies in the fields of Bunker Services, Classification Societies, Consultants and Surveyors, Lawyers and Solicitors, Port Authorities, Ship Builders and Repairers, Stevedores, Ship Chandlers, Shipping Agents, Ship Registries and many more. The directory is available in this printed format and also online at http://directories.lloydslist.com/servicesThis directory will be circulated, seen and continually used as a critical reference point by the vast and influential global readership of Lloyd’s List – over 12,000 senior Executives across the shipping industry that have major purchasing power for their businesses. The Lloyd’s List Maritime Directory of Shipping Services sits within a growing portfolio of sister publications such as the monthly Lloyd’s List Intelligence magazine and Containerisation International Magazine, as well as an extensive range of digital, events and data services products For additional copies of this directory and/or more information on advertising opportunities in this directory please contact Sunil Sharma [email protected] Informa Business Information, Christchurch Court, 10–15 Newgate Street, London, EC1A 7AZ Switchboard: +44 207 017 5000 www.lloydslist.com Informa Business Information is a trading -

Cargo Delivery Without Presentation of the Bill of Lading in Chinese Maritime Law and Practice

Journal of Shipping and Ocean Engineering 6 (2016) 191-205 D doi 10.17265/2159-5879/2016.04.001 DAVID PUBLISHING Cargo Delivery without Presentation of the Bill of Lading in Chinese Maritime Law and Practice Vehbi S. Ataergin Dean Professor of Law School at Near East University Abstract: This chapter examines the Chinese practice of delivery of the cargo without presentation of the bill of lading and the law and regulations governing that practice, and in the gaps left by laws and regulations, the approach established by the legal authorities and maritime courts. The necessities and causes for this risky action and possible suggestions will be considered, as will the approach of statute and judiciary. Potential and desirable reform will be discussed in light of the Rotterdam Rules. It is concluded that in order to facilitate cargo delivery, there would be a need to provide detailed legal guidance applicable to the many situations where the requisite documentation has failed to materialise. Key words: Maritime law, international trade law, Chinese maritime law, cargo delivery, bill of lading. 1. Introduction release of the cargo on board without presentation of the bill of lading, although such practice is the opposite Much carriage of goods by sea is related to an of what the carrier should do to legitimise the delivery international sale contract. The seller has two separate and protect itself from liabilities. Against the sets of duties to perform in accordance with the background of vivid examples of carriers being sued international sale contract: namely, physical duties and for damages and going into bankruptcy, the practice documentary duties. -

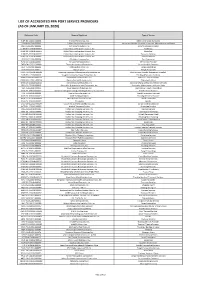

List of Accredited Ppa Port Service Providers (As of January 20, 2020)

LIST OF ACCREDITED PPA PORT SERVICE PROVIDERS (AS OF JANUARY 20, 2020) Reference Code Name of Applicant Type of Service RJDP-OS-112021-000001 R.J. Del Pan and Co., Inc. Marine and Cargo Surveyors SSSI-VR-112018-000003 SubSea Services Incoroprated Vessel and Marine Structure Inspection, Maintenance abd Repair RSSI-OS-112018-000004 RVV Security System, Inc. Security Services Provider GLMS-BU-112018-000005 Global Maritime Logistics Support, Inc. Bunkering GLMS-CD-112018-000005 Global Maritime Logistics Support, Inc. Chandling GLMS-TS-112018-000005 Global Maritime Logistics Support, Inc. Transport Services GLMS-OS-112018-000005 Global Maritime Logistics Support, Inc. Shipping Agency JBCI-OS-112018-000006 JRBuilders Company Inc. Port Contractor FEFC-OS-112018-000007 Far East Fuel Corporation SRF Service Provider TASS-CH-112021-000009 Taurus Arrastre and Stevedoring Cargo Handling Operator DLPI-TS-112018-000010 DRP Logistics Phils., Inc. Cargo Forwarding AJLS-TS-112018-000011 Alljoy Logistics Freight Forwarder OPME-OS-112018-000012 Optimum Equipment Management & Exchange Inc. Port Services Provider (Equipment Supplier) SCCF-TS-112018-000013 Straight Commercial Cargo Forwarders, Inc. Trucking (Transport Services) ONRS-TO-112021-000014 Omnico Natural Resources, Inc. Towing / Tugging Services ONRS-WS-112021-000014 Omnico Natural Resources, Inc. Watering Services ONRS-OS-112021-000014 Omnico Natural Resources, Inc. Cargo Surveying and Cargo Checking Services SRCI-OS-122018-000015 Super-Aire Refrigeration and Contractors, Inc. Preventive Maintenance of Air-con Units YLPI-TS-122018-000016 Yusen Logistics Philippines, Inc. International Freight Forwarding SCHS-PT-122018-000017 Samarenos Integrated Cargo Handling Services, Incorporated Port Terminal Services FCSI-TS-122018-000018 Fivestar Cargo Services, Inc. -

Review of Maritime Transport 2016 Review of Maritime Transport

UNCTAD UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT REVIEW OF MARITIME TRANSPORT For further information on UNCTAD’s work REVIEW on trade logistics, please visit: http://unctad.org/ttl OF MARITIME and for the TRANSPORT Review of Maritime Transport 2016: http://unctad.org/rmt E-mail: 2016 [email protected] To read more and to subscribe to the UNCTAD Transport Newsletter, please visit: http://unctad.org/transportnews 2016 UNITED NATIONS ISBN 978-92-1-112904-5 Layout and printed at United Nations, Geneva 1623510 (E)–November 2016 – 2,102 UNCTAD/RMT/2016 United Nations publication Sales No. E.16.II.D.7 : © Jan Hoffmann Photo credit UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT REVIEW OF MARITIME TRANSPORT 2016 New York and Geneva, 2016 ii REVIEW OF MARITIME TRANSPORT 2016 NOTE The Review of Maritime Transport is a recurrent publication prepared by the UNCTAD secretariat since 1968 with the aim of fostering the transparency of maritime markets and analysing relevant developments. Any factual or editorial corrections that may prove necessary, based on comments made by Governments, will be reflected in a corrigendum to be issued subsequently. * * * Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Use of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. * * * The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Swanland Irish Sea Irish REPORT NO12/2013 JUNE2013 REPORT

ACCIDENT REPORT ACCIDENT VERY SERIOUS MARINE CASUALTY SERIOUSMARINE VERY the structural failure andfoundering the structural failure Report into ontheinvestigation of the general cargo ship cargo of thegeneral withthelossofsixcrew H 27 November 2011 27 November NC RA Swanland Irish Sea N B IO REPORT NO12/2013 JUNE2013 GAT TI S INVE T DEN ACCI RINE MA Extract from The United Kingdom Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2012 – Regulation 5: “The sole objective of the investigation of an accident under the Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2012 shall be the prevention of future accidents through the ascertainment of its causes and circumstances. It shall not be the purpose of an investigation to determine liability nor, except so far as is necessary to achieve its objective, to apportion blame.” NOTE This report is not written with litigation in mind and, pursuant to Regulation 14(14) of the Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 2012, shall be inadmissible in any judicial proceedings whose purpose, or one of whose purposes is to attribute or apportion liability or blame. © Crown copyright, 2013 You may re-use this document/publication (not including departmental or agency logos) free of charge in any format or medium. You must re-use it accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and you must give the title of the source publication. Where we have identified any third party copyright material -

In the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas Houston Division

Case 4:09-cv-00702 Document 61 Filed in TXSD on 06/15/10 Page 1 of 23 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION QT TRADING, LP, § § Plaintiff, § § v. § CIVIL ACTION NO. 4:09-702 § M/V SAGA MORUS, her engines, § tackle, boilers, etc., DAEWOO § LOGISTICS CORP.; ATTIC FOREST § AS; PATT, MANFIELD & CO. § LTD.; and SAGA FOREST CARRIERS § INTERNATIONAL AS, § § Defendants. § MEMORANDUM AND ORDER In this admiralty and maritime case alleging damage to Plaintiff’s cargo, Defendants Saga Forest Carriers International AS, Attic Forest AS and Patt Manfield & Co. Ltd. have filed a Motion for Summary Judgment [Doc. # 37] (“Motion”). Plaintiff QT Trading, LP, has filed a response,1 and Defendants have replied.2 The 1 Plaintiff’s Response to Defendant’s Motion for Summary Judgment and Plaintiff’s Cross-Motion for Partial Summary Judgment on the Liability of Defendants [Doc. # 42] (“Response”). Plaintiff’s counsel filed duplicate documents on ECF and, although the actual scanned document has the same caption in all three documents, counsel entered different captions on ECF. See Unopposed Motion for Partial Summary Judgment on the Liability of Defendants [Doc. # 43] (duplicate of Doc. # 42); Response to Motion for Summary Judgment [Doc. # 44] (duplicate of Doc. # 42). (continued...) P:\ORDERS\11-2009\702MSJ.wpd 100615.1239 Case 4:09-cv-00702 Document 61 Filed in TXSD on 06/15/10 Page 2 of 23 Motion now is ripe for decision. Having considered the parties’ briefing, the applicable legal authorities, and all matters of record, the Court concludes that Defendants’ Motion should be granted. -

China Shipping( Group) Company Corporate Social Responsibility Report

China Shipping( Group) Company Corporate Social Responsibility Report 2012 About This Report Overview Dear stakeholders, this is the second social responsibility report released by China Shipping (Group) Company. The report describes our concepts, strategies and management approaches to sustainability. It also elaborates on our efforts and achievements in fulfilling safety, economic, environmental, employee and social commitments as well as the comments of stakeholders. Compilation Basis This report is prepared in accordance with the Guideline on Fulfilling Social Responsibility by Central Enterprises released by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) of the State Council, the Sustainability Reporting Guidelines (G3.1) of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the Chinese CSR Report Preparation Guide (CASS-CSR 2.0). Reporting Period This report covers the period between January 1 and December 31, 2012, with some expressions and data appropriately dating back to earlier years. Release Cycle The report is released annually. Reporting Scope This report covers information about all tier-1 subsidiaries, some tier-2 subsidiaries, shareholding companies and joint ventures of China Shipping (Group) Company. Data Source Data in this report is derived from in-house documents and related statistics of China Shipping (Group) Company. References For readability purposes, any reference to "China Shipping", "the Group", or "we" in this report refers to China Shipping (Group) Company. Accesses to This Report This -

Agency Fees Page 1 of 16 Revision 01/2006

PORT OF TRIESTE AGENCY FEES PAGE 1 OF 16 REVISION 01/2006 AGENCY FEES Decree 22 February 2011 ART.1 VESSELS NOT EFFECTING COMMERCIAL OPERATIONS a) For vessels not effecting commercial operations, calling to receive orders, for provisions, for dry docking and/or bunkering purposes, for requirements concerning the crew, or for similar cases, the following tariffs shall be charged, with an allowance of plus/minus 5%: up to 4.000 GRT Euro 759,00 from 4.001 a 9.000 “ “ 984,00 “ 9.001 “ 12.000 “ “ 1.205,00 “ 12.001 “ 18.000 “ “ 1.290,00 “ 18.001 “ 26.000 “ “ 1.388,00 “ 26.001 “ 35.000 “ “ 1.559,00 “ 35.001 “ 45.000 “ “ 1.773,00 “ 45.001 “ 55.000 “ “ 2.044,00 “ 55.001 “ 65.000 “ “ 2.316,00 “ 65.001 “ 75.000 “ “ 2.581,00 “ 75.001 “ 85.000 “ “ 2.929,00 over 85.000 an increase of Euro 0,05 for each GRT up to a maximum of Euro 3.871,00 for each call. For vessels remaining in port for more than 5 days (including the day of arrival and the day of departure) the Ship Agent is entitled, in addition to the above fees, to an extra fee of 10% on the tariff for each additional day with a maximum amount of Euro 141,00 per day. b) For vessels, for which the Ship Agent is not bound to the rules and provisions referred to articles 3, 4 and 5 of Law 135/77, the following tariffs shall be charged, with an allowance of plus/minus 5%: up to 4.000 GRT Euro 379,00 from 4.001 a 9.000 “ “ 492,00 “ 9.001 “ 12.000 “ “ 594,00 “ 12.001 “ 18.000 “ “ 637,00 “ 18.001 “ 26.000 “ “ 686,00 “ 26.001 “ 35.000 “ “ 770,00 “ 35.001 “ 45.000 “ “ 878,00 “ 45.001 “ 55.000 “ “ 1.009,00 “ 55.001 “ 65.000 “ “ 1.144,00 “ 65.001 “ 75.000 “ “ 1.274,00 “ 75.001 “ 85.000 “ “ 1.446,00 over 85.000 GRT an increase of Euro 0,03 for each GRT up to a maximum of Euro 1.916,00 for each For vessels remaining in port for more than 5 days (including the day of arrival and the day of departure) the Ship Agent is entitled, in addition to the above fees, to an extra fee of 10% on the tariff for each additional day with a maximum amount of Euro 70,00 per day.