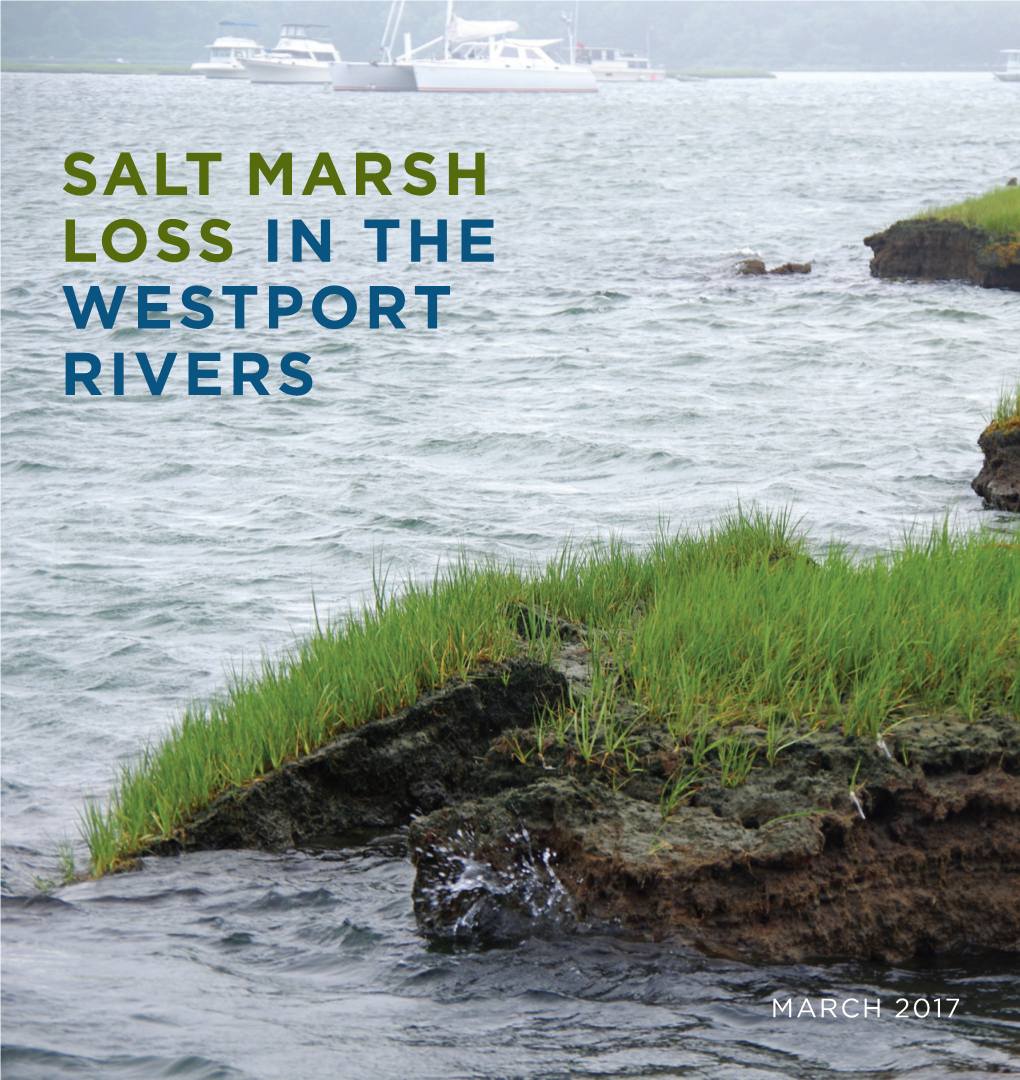

Salt Marsh Loss in the Westport Rivers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brodhead Watershed Conservation Plan

Brodhead Watershed Conservation Plan January, 2002 Prepared by: Brodhead Watershed Association With: BLOSS Associates Brodhead Watershed Conservation Plan Acknowledgements The Watershed Partners were the backbone of this planning process. Their commitment to preserving and protecting the watershed underlies this entire plan. Watershed Partners / Conservation Plan Steering Committee Monroe County Commissioners – Mario Scavello, Donna Asure, James Cadue, Former Commissioner Janet Weidensaul Monroe County Conservation District – Craig Todd, Darryl Speicher Monroe County Planning Commission – John Woodling, Eric Bartolacci Monroe County Historical Association – Candace McGreevey Monroe County Office of Emergency Management – Harry Robidoux Monroe County Open Space Advisory Board – Tom O’Keefe Monroe County Recreation & Park Commission – Kara Derry Monroe 2020 Executive Committee – Charles Vogt PA Department of Environmental Protection – Bill Manner Pennsylvania State University – Jay Stauffer Penn State Cooperative Extension – Peter Wulfhurst Stroudsburg Municipal Authority – Ken Brown Mount Pocono Borough – Nancy Golowich Pocono/Hamilton/Jackson Open Space Committee – Cherie Morris Stroud Township – Ross Ruschman, Ed Cramer Smithfield Township – John Yetter Delaware River Basin Commission – Pamela V’Combe, Carol Collier U.S. Environmental Protection Agency – Susan McDowell Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area – Denise Cook National Park Service, Rivers & Trails Office – David Lange National Institute for Environmental Renewal (no longer -

Comparison of Swamp Forest and Phragmites Australis

COMPARISON OF SWAMP FOREST AND PHRAGMITES AUSTRALIS COMMUNITIES AT MENTOR MARSH, MENTOR, OHIO A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Jenica Poznik, B. S. ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Master's Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Craig Davis, Advisor Dr. Peter Curtis Dr. Jeffery Reutter School of Natural Resources ABSTRACT Two intermixed plant communities within a single wetland were studied. The plant community of Mentor Marsh changed over a period of years beginning in the late 1950’s from an ash-elm-maple swamp forest to a wetland dominated by Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steudel. Causes cited for the dieback of the forest include salt intrusion from a salt fill near the marsh, influence of nutrient runoff from the upland community, and initially higher water levels in the marsh. The area studied contains a mixture of swamp forest and P. australis-dominated communities. Canopy cover was examined as a factor limiting the dominance of P. australis within the marsh. It was found that canopy openness below 7% posed a limitation to the dominance of P. australis where a continuous tree canopy was present. P. australis was also shown to reduce diversity at sites were it dominated, and canopy openness did not fully explain this reduction in diversity. Canopy cover, disturbance history, and other environmental factors play a role in the community composition and diversity. Possible factors to consider in restoring the marsh are discussed. KEYWORDS: Phragmites australis, invasive species, canopy cover, Mentor Marsh ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A project like this is only possible in a community, and more people have contributed to me than I can remember. -

Alternative Stable States of Tidal Marsh Vegetation Patterns and Channel Complexity

ECOHYDROLOGY Ecohydrol. (2016) Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/eco.1755 Alternative stable states of tidal marsh vegetation patterns and channel complexity K. B. Moffett1* and S. M. Gorelick2 1 School of the Environment, Washington State University Vancouver, Vancouver, WA, USA 2 Department of Earth System Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA ABSTRACT Intertidal marshes develop between uplands and mudflats, and develop vegetation zonation, via biogeomorphic feedbacks. Is the spatial configuration of vegetation and channels also biogeomorphically organized at the intermediate, marsh-scale? We used high-resolution aerial photographs and a decision-tree procedure to categorize marsh vegetation patterns and channel geometries for 113 tidal marshes in San Francisco Bay estuary and assessed these patterns’ relations to site characteristics. Interpretation was further informed by generalized linear mixed models using pattern-quantifying metrics from object-based image analysis to predict vegetation and channel pattern complexity. Vegetation pattern complexity was significantly related to marsh salinity but independent of marsh age and elevation. Channel complexity was significantly related to marsh age but independent of salinity and elevation. Vegetation pattern complexity and channel complexity were significantly related, forming two prevalent biogeomorphic states: complex versus simple vegetation-and-channel configurations. That this correspondence held across marsh ages (decades to millennia) -

Maritime Swamp Forest (Typic Subtype)

MARITIME SWAMP FOREST (TYPIC SUBTYPE) Concept: Maritime Swamp Forests are wetland forests of barrier islands and comparable coastal spits and back-barrier islands, dominated by tall trees of various species. The Typic Subtype includes most examples, which are not dominated by Acer, Nyssa, or Fraxinus, not by Taxodium distichum. Canopy dominants are quite variable among the few examples. Distinguishing Features: Maritime Shrub Swamps are distinguished from other barrier island wetlands by dominance by tree species of (at least potentially) large stature. The Typic Subtype is dominated by combinations of Nyssa, Fraxinus, Liquidambar, Acer, or Quercus nigra, rather than by Taxodium or Salix. Maritime Shrub Swamps are dominated by tall shrubs or small trees, particularly Salix, Persea, or wetland Cornus. Some portions of Maritime Evergreen Forest are marginally wet, but such areas are distinguished by the characteristic canopy dominants of that type, such as Quercus virginiana, Quercus hemisphaerica, or Pinus taeda. The lower strata also are distinctive, with wetland species occurring in Maritime Swamp Forest; however, some species, such as Morella cerifera, may occur in both. Synonyms: Acer rubrum - Nyssa biflora - (Liquidambar styraciflua, Fraxinus sp.) Maritime Swamp Forest (CEGL004082). Ecological Systems: Central Atlantic Coastal Plain Maritime Forest (CES203.261). Sites: Maritime Swamp Forests occur on barrier islands and comparable spits, in well-protected dune swales, edges of dune ridges, and on flats adjacent to freshwater sounds. Soils: Soils are wet sands or mucky sands, most often mapped as Duckston (Typic Psammaquent) or Conaby (Histic Humaquept). Hydrology: Most Maritime Swamp Forests have shallow seasonal standing water and nearly permanently saturated soils. Some may rarely be flooded by salt water during severe storms, but areas that are severely or repeatedly flooded do not recover to swamp forest. -

Delaware Bay Estuary Project Supporting the Conservation and Restoration Of

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service – Coastal Program Delaware Bay Estuary Project Supporting the conservation and restoration of the salt marshes of Delaware Bay People have altered the expansive salt marshes of Delaware Bay for centuries to farm salt hay, try to control mosquitoes, create channels for boats, to increase developable land, and other reasons all resulting in restricted tidal flow, disrupted sediment balances, or increasing erosion. Sea level rise and coastal storms threaten to further negatively impact the integrity of these salt marshes. As we alter or lose the marshes we lose the valuable habitats and ecological services they provide. tidal creek - Katherine Whittemore Addressing the all-important sediment balance of salt marshes is critical for preserving their resilience. A healthy resilient marsh may be able to keep pace with erosion and sea level rise through sediment accretion and growth Downe Twsp, NJ - Brian Marsh of vegetation. However, the delicate sediment balance of salt marshes is DBEP works to support efforts to learn more about the techniques often disrupted by barriers to tidal influence and altered drainage onto and to conserve and restore salt marshes and support the populations of fish and wildlife that rely on them. We support new and off the marsh resulting in sediment ongoing coastal resiliency initiatives and coastal planning as they starved systems, excessive mudflats, or pertain to habitat restoration and conservation. We are interested increased erosion. in finding effective tools and mechanisms for conserving and restoring salt marsh integrity on a meaningful scale and support efforts that bring partners together to approach this challenge. -

Marsh-Pond-Marsh Constructed Wetland Design Analysis for Swine Lagoon Wastewater Treatment

Ecological Engineering 23 (2004) 127–133 Marsh-pond-marsh constructed wetland design analysis for swine lagoon wastewater treatment K.C. Stonea,∗, M.E. Poacha, P.G. Hunta, G.B. Reddyb a USDA-ARS, 2611 West Lucas Street, Florence, SC 29501, USA b North Carolina A&T State University, Greensboro, NC, USA. Received 29 March 2004; received in revised form 23 July 2004; accepted 26 July 2004 Abstract Constructed wetlands have been identified as a potentially important component of animal wastewater treatment systems. Continuous marsh constructed wetlands have been shown to be effective in treating swine lagoon effluent and reducing the land needed for terminal application. Constructed wetlands have also been used widely in polishing wastewater from municipal systems. Constructed wetland design for animal wastewater treatment has largely been based on that of municipal systems. The objective of this research was to determine if a marsh-pond-marsh wetland system could be described using existing design approaches used for constructed wetland design. The marsh-pond-marsh wetlands investigated in this study were constructed in 1995 at the North Carolina A&T University research farm near Greensboro, NC. There were six wetland systems (11 m × 40 m). The first 10-m was a marsh followed by a 20-m pond section followed by a 10-m marsh planted with bulrushes and cattails. The wetlands were effective in treating nitrogen with mean total nitrogen and ammonia-N concentration reductions of approximately 30%; however, they were not as effective in the treatment of phosphorus (8%). Outflow concentrations were reasonably correlated (r2 ≥ 0.86 and r2 ≥ 0.83, respectively) to inflow concentrations and hydraulic loading rates for both total N and ammonia-N. -

Exploring Our Wonderful Wetlands Publication

Exploring Our Wonderful Wetlands Student Publication Grades 4–7 Dear Wetland Students: Are you ready to explore our wonderful wetlands? We hope so! To help you learn about several types of wetlands in our area, we are taking you on a series of explorations. As you move through the publication, be sure to test your wetland wit and write about wetlands before moving on to the next exploration. By exploring our wonderful wetlands, we hope that you will appreciate where you live and encourage others to help protect our precious natural resources. Let’s begin our exploration now! Southwest Florida Water Management District Exploring Our Wonderful Wetlands Exploration 1 Wading Into Our Wetlands ................................................Page 3 Exploration 2 Searching Our Saltwater Wetlands .................................Page 5 Exploration 3 Finding Out About Our Freshwater Wetlands .............Page 7 Exploration 4 Discovering What Wetlands Do .................................... Page 10 Exploration 5 Becoming Protectors of Our Wetlands ........................Page 14 Wetlands Activities .............................................................Page 17 Websites ................................................................................Page 20 Visit the Southwest Florida Water Management District’s website at WaterMatters.org. Exploration 1 Wading Into Our Wetlands What exactly is a wetland? The scientific and legal definitions of wetlands differ. In 1984, when the Florida Legislature passed a Wetlands Protection Act, they decided to use a plant list containing plants usually found in wetlands. We are very fortunate to have a lot of wetlands in Florida. In fact, Florida has the third largest wetland acreage in the United States. The term wetlands includes a wide variety of aquatic habitats. Wetland ecosystems include swamps, marshes, wet meadows, bogs and fens. Essentially, wetlands are transitional areas between dry uplands and aquatic systems such as lakes, rivers or oceans. -

The Annual Net Primary Production and Decomposition of the Salt Marsh Grass, Spartina Alterniflora, Loisel. in the Barataria Bay Estuary of Louisiana

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 The Annual Net Primary Production and Decomposition of the Salt Marsh Grass, Spartina Alterniflora, Loisel. In the Barataria Bay Estuary of Louisiana. Conrad Joseph Kirby Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Kirby, Conrad Joseph Jr, "The Annual Net Primary Production and Decomposition of the Salt Marsh Grass, Spartina Alterniflora, Loisel. In the Barataria Bay Estuary of Louisiana." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2139. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2139 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. -

Life Cycle of Oil and Gas Fields in the Mississippi River Delta: a Review

water Review Life Cycle of Oil and Gas Fields in the Mississippi River Delta: A Review John W. Day 1,*, H. C. Clark 2, Chandong Chang 3 , Rachael Hunter 4,* and Charles R. Norman 5 1 Department of Oceanography and Coastal Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA 2 Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Science, Rice University, Houston, TX 77005, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Geological Sciences, Chungnam National University, Daejeon 34134, Korea; [email protected] 4 Comite Resources, Inc., P.O. Box 66596, Baton Rouge, LA 70896, USA 5 Charles Norman & Associates, P.O. Box 5715, Lake Charles LA 70606, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.W.D.); [email protected] (R.H.) Received: 20 April 2020; Accepted: 20 May 2020; Published: 23 May 2020 Abstract: Oil and gas (O&G) activity has been pervasive in the Mississippi River Delta (MRD). Here we review the life cycle of O&G fields in the MRD focusing on the production history and resulting environmental impacts and show how cumulative impacts affect coastal ecosystems. Individual fields can last 40–60 years and most wells are in the final stages of production. Production increased rapidly reaching a peak around 1970 and then declined. Produced water lagged O&G and was generally higher during declining O&G production, making up about 70% of total liquids. Much of the wetland loss in the delta is associated with O&G activities. These have contributed in three major ways to wetland loss including alteration of surface hydrology, induced subsidence due to fluids removal and fault activation, and toxic stress due to spilled oil and produced water. -

MUD CREATURE STUDY Overview: the Mudflats Support a Tremendous Amount of Life

MUD CREATURE STUDY Overview: The mudflats support a tremendous amount of life. In this activity, students will search for and study the creatures that live in bay mud. Content Standards Correlations: Science p. 307 Grades: K-6 TIME FRAME fOR TEACHING THIS ACTIVITY Key Concepts: Mud creatures live in high abundance in the Recommended Time: 30 minutes mudflats, providing food for Mud Creature Banner (7 minutes) migratory ducks and shorebirds • use the Mud Creature Banner to introduce students to mudflat and the endangered California habitat clapper rail. When the tide is out, Mudflat Food Pyramid (3 minutes) the mudflats are revealed and birds land on the mudflats to feed. • discuss the mudflat food pyramid, using poster Mud Creature Study (20 minutes) Objectives: • sieve mud in sieve set, using slough water Students will be able to: • distribute small samples of mud to petri dishes • name and describe two to three • look for mud creatures using hand lenses mud creatures • describe the mudflat food • use the microscopes for a closer view of mud creatures pyramid • if data sheets and pencils are provided, students can draw what • explain the importance of the they find mudflat habitat for migratory birds and endangered species Materials: How THIS ACTIVITY RELATES TO THE REFUGE'S RESOURCES Provided by the Refuge: What are the Refuge's resources? • 1 set mud creature ID cards • significant wildlife habitat • 1 mud creature flannel banner • endangered species • 1 mudflat food pyramid poster • 1 mud creature ID book • rhigratory birds • 1 four-layered sieve set What makes it necessary to manage the resources? • 1 dish of mud and trowel • Pollution, such as oil, paint, and household cleaners, when • 1 bucket of slough water dumped down storm drains enters the slough and mudflats and • 1 pitcher of slough water travels through the food chain, harming animals. -

Marsh Futures Use of Scientific Survey Tools to Assess Local Salt Marsh Vulnerability and Chart Best Management Practices and Interventions

Partnership for the Delaware Estuary Marsh Futures Use of scientific survey tools to assess local salt marsh vulnerability and chart best management practices and interventions A technical report submitted in support of the Bayshore Sustainable Infrastructure Planning Project (BaySIPP) and funded by the grant, “Creating a Sustainable Infrastructure Plan for the South Jersey Bayshore” 2015 PDE Report No. 15-03, January 2015 Page i Marsh Futures: use of scientific survey tools to assess local salt marsh vulnerability and chart best management practices and interventions. Danielle Kreeger, Ph.D. Joshua Moody Partnership for the Delaware Estuary 110 South Poplar Street, Suite 202 Wilmington, DE 19801 Moses Katkowski The Nature Conservancy Eldora, NJ Megan Boatright Diane Rosencrance Natural Lands Trust 1031 Palmers Mill Road Media, PA 19063 Acknowledgments: Funding for this project was provided by a grant from the New Jersey Recovery Fund in support of the project titled “Creating a Sustainable Infrastructure Plan for the South Jersey Bayshore.” We are grateful to the many community leaders who provided their input on salt marsh tracts of greatest concern in the studied areas of interest, including Meghan Wren, Bob Campbell, Ben Stowman, Phillip Tomlinson, Kathy Ireland, and Barney Hollinger. Special thanks are extended to Sari Rothrock from the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary (PDE) who guided the overall Bayshore Sustainable Infrastructure Planning Project (BaySIPP). Angela Padeletti assisted with her project management and scheduling prowess at PDE. Danielle Kreeger (PDE) served as principal investigator for this project. Field efforts were led by Joshua Moody (PDE) and Moses Katkowski from The Nature Conservancy (TNC). Diane Rosencrance and Megan Boatright from Natural Lands Trust (NLT) acquired historic and modern remote sensing data, and tracked shoreline retreat rates. -

Salt Marsh Monitoring by The

SaltSalt MarshMarsh MonitoringMonitoring byby thethe U.S.U.S. FishFish && WildlifeWildlife ServiceService’’ss NortheastNortheast RegionRegion Ralph Tiner Regional Wetland Coordinator U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service-Northeast Region February 2010 TypesTypes ofof MonitoringMonitoring RemotelyRemotely sensedsensed MonitoringMonitoring Area and type changes (e.g., trends analysis) Can cover large or small areas OnOn--thethe--groundground MonitoringMonitoring Addressing processes (accretion, erosion, subsidence, salt balance, etc.) Analyzing vegetation and soil changes Plot analysis Reference wetlands Evaluating wildlife habitat RemotelyRemotely SensedSensed MonitoringMonitoring NWINWI usesuses aerialaerial imageryimagery toto tracktrack wetlandwetland changeschanges inin wetlandwetland typetype WetlandWetland StatusStatus && TrendsTrends StudiesStudies == aa typetype ofof monitoringmonitoring For large geographic areas Statistical Sampling – analyze changes in 4-square mile plots; generate estimates For small areas Area-based Analysis –analyze complete area for changes over time RegionRegion vsvs LocalLocal ReportsReports CanfieldCanfield Cove,Cove, CTCT 19741974 20042004 Canfield Island Cove 60 50 40 s e 30 Acr 20 10 0 1974 1981 1986 1990 1995 2000 2004 Low Marsh High Marsh Flat ConsiderationsConsiderations forfor SiteSite--specificspecific MonitoringMonitoring SpecialSpecial aerialaerial imageryimagery LowLow tidetide PeakPeak ofof growinggrowing seasonseason NormalNormal issuesissues re:re: qualityquality (e.g.,(e.g.,