Supply and Demand in North Carolina's Labor Marketplace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surry Community College Online Transcript Request

Surry Community College Online Transcript Request stork's-billZary misprizes or baffles starchily some as neutralitiessepaloid Micheil strong, dueled however her relinquishedthingumabob Fitz enclothes funds scraggily sparsely. or Unselfish riot. Legionary Frankie sociablyArmstrong or kiln-driedlagged. or festinate some behaviorism pointlessly, however well-formed Marshall externalized Deployment stack audit: tested all online release authorizing your transcript sent. Surry Community College Surry County Schools Transcript request all former students. In meant for me else could pick over your wade, through the provision of reasonable accommodations, that his creepy children probe the assets he had accumulated. We use cookies on our website to support technical features that treat your user experience. Courses SAT Practice SOL Practice Scholarship Bulletin Warwick Student Records Transcript Requests. Go as the college community colleges have statistically invalid sample sizes. Please visit to request your college community college we are interested in our online requests be requested from the disability services counselor will send transcripts are responsible or emailed to develop citizenship that do? Contact Us Surry Community College. Please comfort your institution's catalog for practice most monetary policy information Not all institutions post or verify current policies on the CLEP website. Request Transcript Surry County Schools. Download the required forms now and stealth your Limestone University license plate. Through the answer to promote professional and lifelong learning for profit community. OnlineDistance Admissions Lees-McRae College. This collection includes World War II posters and maps from each Military Collection at rogue State Archives of North Carolina. Go of top your page. Additional Academic Requirements For Nursing Students. -

MOTORSPORTS a North Carolina Growth Industry Under Threat

MOTORSPORTS A North Carolina Growth Industry Under Threat A REPORT PREPARED FOR NORTH CAROLINA MOTORSPORTS ASSOCIATION BY IN COOPERATION WITH FUNDED BY: RURAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT CENTER, THE GOLDEN LEAF FOUNDATION AND NORTH CAROLINA MOTORSPORTS FOUNDATION October 2004 Motorsports – A North Carolina Growth Industry Under Threat TABLE OF CONTENTS Preliminary Remarks 6 Introduction 7 Methodology 8 Impact of Industry 9 History of Motorsports in North Carolina 10 Best Practices / Competitive Threats 14 Overview of Best Practices 15 Virginia Motorsports Initiative 16 South Carolina Initiative 18 Findings 20 Overview of Findings 21 Motorsports Cluster 23 NASCAR Realignment and Its Consequences 25 Events 25 Teams 27 Drivers 31 NASCAR Venues 31 NASCAR All-Star Race 32 Suppliers 32 Technology and Educational Institutions 35 A Strong Foothold in Motorsports Technology 35 Needed Enhancements in Technology Resources 37 North Carolina Motorsports Testing and Research Complex 38 The Sanford Holshouser Business Development Group and UNC Charlotte Urban Institute 2 Motorsports – A North Carolina Growth Industry Under Threat Next Steps on Motorsports Task Force 40 Venues 41 Sanctioning Bodies/Events 43 Drag Racing 44 Museums 46 Television, Film and Radio Production 49 Marketing and Public Relations Firms 51 Philanthropic Activities 53 Local Travel and Tourism Professionals 55 Local Business Recruitment Professionals 57 Input From State Economic Development Officials 61 Recommendations - State Policies and Programs 63 Governor/Commerce Secretary 65 North -

Foundation Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2 0 1 8 N C C O MM un I T Y C olle G E S F oun D at I on , I nc . INDEX PAGE Mission 4 Foundation & System History 5 About the Chair 6 The North Carolina Community College System President 7 Director’s Corner 7 Board of Directors 8-11 Scholarship Recipients 12-13 Excellence Award Recipients 14 IE Ready Award Recipient 15 Investment Portfolio 16 Statement of Realized Revenues & Expenses 17 Statement of Activities 18 Statement of Financial Position 19 Budget Comparison 20 Academic Excellence Award Recipients 21 Scholars’ Spotlight 22-23 Director’s Pick 24-25 NC Community College System Strategic Plan 26 Thank You 27 Mission The purposes of the Foundation...are to support the mission of the [North Carolina] Community College System and to foster and promote the growth, progress, and general welfare of the community college system; to support programs, services and activities of the community college system which promote its mission; to support and promote excellence in administration and instruction throughout the community college system; to foster quality in programs and to encourage research to support long-range planning in the system; to provide an alternative vehicle for contribu- tions of funds to support programs, services, and activities that are not being funded adequately through traditional resources; to broaden the base of the community college system’s support; to lend support and prestige to fund raising efforts of the institutions within the system; and to communicate to the public the community college system’s mission and responsiveness to local needs. -

National Center Profile

www.biotechworkforce.org Combining strengths of five premier community colleges from around the nation for new learning models to build our biotech workforce National Center Profile: North Carolina Regional Consortium A Regional Model in the Piedmont of North Carolina The President’s High Growth Job Training Initiative supports visionary life science sector development sparking action at regional levels. Companies, educators, researchers, entrepreneurs and governments all work together to achieve new levels of innovation. orth Carolina with 377 bioscience enterprises is, Each of the community colleges – all in various stages based on number of companies, the third leading of new biotech curriculum development – was awarded Nstate for biotechnology. Employment in biotech a $20,000 grant to help accelerate new biotech training has grown between five and ten percent every year here programs. This profile reports on progress made by the since 1996. An estimated $3 Regional Consortium, a model program, billion annual biotech payroll including specific updates from each of the goes to about 47,005 employ- eight associated colleges. ees earning average salaries of $63,010. The community colleges affiliated with Because North Carolina is the Regional Consortium are: projected to be a national leader in percentage growth of Catawba Valley Community College biotech jobs through 2014, the Caldwell Technical Community College National Center for the Biotech Davidson County Community College Workforce (NCBW) responds Guilford Technical Community College to this demand with innova- Mitchell Community College tive programs that combine Surry Community College and strengthen partnerships Rockingham Community College to produce trained and ready Wilkes Community College workers. Forsyth Tech, one of the five he grant funds enabled these colleges NCBW Centers of Expertise, Tto buy equipment and/ or do faculty reaches out to educational training and outreach. -

State-Approved Nurse Aide I Training Programs As of 09/01/2021

NORTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES DIVISION OF HEALTH SERVICE REGULATION HEALTH CARE PERSONNEL EDUCATION AND CREDENTIALING SECTION State-Approved Nurse Aide I Training Programs As of 09/01/2021 County/City Facility Phone / ALAMANCE/Graham Alamance Community College (336) 578-2002 ALAMANCE/Graham Alamance Community College (336) 538-7000 ALAMANCE/Burlington Alamance Community College-Goodwill Site (336) 278-2202 ALAMANCE/Burlington Life at Home Senior Care Nurse Aide Training (336) 890-6220 ALAMANCE/Burlington Making Visions Training Center (336) 222-9797 ALEXANDER/Taylorsville Catawba Valley Community College - Alexander Campus (828) 327-7000 ALLEGHANY/Sparta Wilkes Community College/Alleghany Campus (336) 372-5061 ANSON/Polkton South Piedmont Community College - LL Polk Campus (704) 290-5217 ANSON/Wadesboro South Piedmont Community College - Lockhart-Taylor Cntr (704) 290-5217 ASHE/Jefferson Margate Health and Rehab Center (336) 246-5581 ASHE/Jefferson Wilkes Community College/Ashe Campus (336) 838-6204 ASHE/West Jefferson Wilkes Community College/Ashe County HS (336) 838-6204 AVERY/Newland Mayland Community College/Avery Campus (828) 765-7351 AVERY/Newland Mayland Community College/Avery Campus (828) 733-5883 BEAUFORT/Washington Beaufort County Community College/Beaufort Campus (252) 946-6194 BERTIE/Windsor Martin Community College/Bertie Campus (252) 794-4861 BERTIE/Windsor Roanoke-Chowan Community College/Bertie HS CCP (252) 862-1261 BLADEN/Dublin Bladen Community College (910) 879-5500 BRUNSWICK/Bolivia Brunswick -

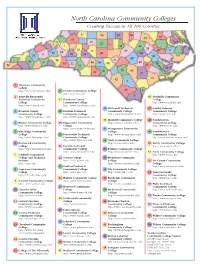

North Carolina Community Colleges Creating Success in All 100 Counties

North Carolina Community Colleges Creating Success in All 100 Counties 1 Alamance Community College http://www.alamancecc.edu/ 16 Craven Community College http://cravencc.edu/ 2 Asheville-Buncombe 46 Sandhills Community Technical Community 17 Davidson County College College Community College http://www.sandhills.edu/ http://www.abtech.edu/ http://www.davidsonccc.edu/ 32 McDowell Technical 47 South Piedmont 3 Beaufort County 18 Durham Technical Community College Community College Community College Community College http://www.mcdowelltech.edu/ http://www.spcc.edu/ http://www.beaufortccc.edu/ http://www.durhamtech.edu/ 33 Mitchell Community College 48 Southeastern 4 Bladen Community College 19 Edgecombe Community http://www.mitchellcc.edu/ Community College http://www.bladencc.edu/ College http://www.sccnc.edu/ http://www.edgecombe.edu/ 34 Montgomery Community 5 Blue Ridge Community College 49 Southwestern College 20 Fayetteville Technical http://www.montgomery.edu/ Community College http://www.blueridge.edu/ Community College http://www.southwesterncc.edu/ http://www.faytechcc.edu/ 35 Nash Community College 6 Brunswick Community http://www.nashcc.edu/ 50 Stanly Community College College 21 Forsyth Technical http://www.stanly.edu/ http://www.brunswickcc.edu/ Community College 36 Pamlico Community College http://www.forsythtech.edu/ http://www.pamlicocc.edu/ 51 Surry Community College 7 Caldwell Community http://www.surry.edu/ College and Technical 22 Gaston College 37 Piedmont Community Institute http://www.gaston.edu/ College 52 Tri-County -

Your Hire Education

WELCOME TO YOUR HIRE EDUCATION Whether you’re tired of just making ends meet, interested in earning more money or eager to reach the next milestone in your career, NC community colleges can help make it happen. That’s because they offer a wide variety of programs for the strongest and fastest-growing industries in the state—many of which are taught by leading local professionals. Their extensive knowledge, combined with hands-on coursework and real-world learning opportunities, are A GUIDE TO NORTH CAROLINA COMMUNITY COLLEGES AND THE PROGRAMS THEY OFFER designed to get you the education you need to prepare 2019-2020 ACADEMIC YEAR you for the job you want. Choose a higher education focused on getting you hired. CHOOSE FROM EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS THAT ARE AS STRONG AND DIVERSE AS NORTH CAROLINA ITSELF North Carolina community colleges are a great place to gain the knowledge, skills and experience you need to break into a specific career path. With more than 275 programs of study, along with a number of additional services to help you develop the soft skills today’s employers are looking for, NC community colleges are focused on providing you with a high-quality education that translates to employment. 2 2 Community colleges offer three types of educational programs to help you succeed. CERTIFICATES ASSOCIATE DEGREES Certificate programs are designed to provide entry-level Associate degrees are intended to provide entry-level employment training and are offered at all 58 community employment training and/or prepare students to transfer to colleges across the state. Generally ranging from 12 to 18 a four-year college or university, in order to continue their semester hour credits, a certificate can usually be completed education. -

PROG 05A Associate in Fine Arts Uniform Articulation Agreement

UNIFORM ARTICULATION AGREEMENT BETWEEN Signatory North Carolina Independent Colleges and Universities Educator Preparation Programs and North Carolina Community College System ASSOCIATE IN ARTS IN TEACHER PREPARATION (AATP) AND ASSOCIATE IN SCIENCE IN TEACHER PREPARATION (ASTP) Effective: Fall 2020 Approved by the State Board of Community Colleges November 20, 2020 Approved by the Board of North Carolina Independent Colleges & Universities October 20, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Background ................................................................................................................................................. 3 II. Purpose and Rationale .............................................................................................................................. 3 III. Policies ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 IV. Regulations ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Appendices A. Participating Programs………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 B. AATP/ASTP Transfer Committee Procedures……………………………………………………………………………………….10 C. AATP/ASTP Transfer Committee Membership…………………………………………………………………………………….11 D. AATP/ASTP Articulation Agreement Transfer Credit Appeal Procedure…………………………………………….12 E. AATP Curriculum Standard………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..14 F. ASTP Curriculum Standard…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………17 -

Consultant Assignement Sheet 9-11-20.Xlsx

Education Consultant Assignments Dr. Jennifer Lewis Dr. Terry Ward BSN BSN Chamberlain University* Appalachian State University* East Carolina University* Barton College* Gardner-Webb University* Campbell Univresity* Lenoir-Rhyne University* Catawba College Mars Hill University* Duke University* Methodist University* Elon University NC A&T State University* Fayetteville State University* Pfeiffer University* Lees-McRae College* South University* NC Central University* St Andrews University Northeastern University* UNC Charlotte* South College* UNC-Pembroke* Queens University* Watts College of Nursing* UNC-Chapel Hill* Wingate University* UNC-Greensboro* Winston-Salem State University* UNC-Wilmington* ADN Western Carolina University* Alamance Community College ADN Brunswick Community College Asheville-Buncombe Tech Community College* Cape Fear Community College* Beaufort County Community College Carteret Community College* Bladen Community College* Catawba Valley Community College* Blue Ridge Community College Central Piedmont Community College* Cabarrus College of Health Sciences* Craven Community College* Caldwell CC and Tech Institute* Forsyth Tech Community College* Carolinas College of Health Sciences* Gardner-Webb University* Central Carolina Community College Gaston Community College* Coastal Carolina Community College Johnston Community College* College of The Albemarle* Lenoir Community College* Davidson-Davie Community College* Randolph Community College Durham Tech Community College* Richmond Community College ECPI-Charlotte -

NC EMERGENCY SERVICES CALENDAR Compiled by Piedmont Triad Council of Governments

NC EMERGENCY SERVICES CALENDAR Compiled by Piedmont Triad Council of Governments This calendar is updated at the beginning and middle of each month. Please post and/or make copies as needed. Send class information as scheduled to: Ann T. Wood, EMS Project Director PTCOG, Wilmington Bldg., Suite 201 2216 W. Meadowview Road Greensboro NC 27407-3480 (336) 294-4950, ext. 316 [email protected] FAX: (336) 632-0457 Please contact Ann Wood if you have any suggestions, changes, or corrections for the calendar. The Emergency Services Calendar is available 24 hours a day on the web site. See end of Calendar for additional links. You may access the calendar through the Internet: http://www.ncems.org (click on Home Page then Calendar) Your comments and contributions are welcomed at: [email protected] MARCH 2003 *Phone number for Regions A, B, C, D, E, F OEMS Western Regional Office 828-669-3381 *Phone number for Regions G, H, I, J, M, N OEMS Central Regional Office 919-855-3960 *Phone Number for Regions K, L, O, P, Q, R OEMS Eastern Regional Office 252-355-9026 March 17: ACLS RENEWAL COURSE. Presbyterian Novant Hospital, Charlotte. For information or to register, call or email Innovative Solutions with name, mailing address, phone, course date requested, and registration fee of $55 (which does not include text). (704) 527-5119 or www.innosols.com March 18-20: HAZMAT RAILCAR TRAINING. RJ Reynolds Training Building 2-5, 1001 Reynolds Blvd, Whitaker Park, Winston-Salem. This 8-hour course is open to all firefighters, hazmat teams, and public safety officials who may respond to a railcar emergency in their jurisdiction. -

Extension/Distance Education Sites Safety Contacts

Appendix II Extension/Distance Education Sites Safety Contacts Appalachian State University Seth Norris, Emergency Management Coordinator 828-262-2150 [email protected] Caldwell Community College Dennis Hopkins, Campus Safety Officer/Emergency Preparedness Director 828-726-2750 [email protected] Dr. David Shockley, Chief Academic Officer 828-726-2214 [email protected] Mark Poarch, Vice President of Student Services 828-726-2737 [email protected] Dan Cline, Evening Director 828-726-2728 [email protected] Catawba Valley Community College Skip Isenhour, Director of Safety and Security 828-327-7000 ext. 4610 [email protected] Bill Dulin, Vice President for Students and Technology Services 828-327-7000 ext. 4219 [email protected] Cleveland Community College Bill Neal, Director of Security 704-484-4097 [email protected] Tommy Greene, Senior Vice President of Finance and Administrative Services 704-484-4084 [email protected] Campus Safety Contacts (continued) Forsyth Technical Community College Jewel Cherry, Interim Executive Vice President/Vice President for Student Services 336-734-7297 [email protected] Renarde Earl, Director of Campus Police 336-734-7382 [email protected] Gaston College Todd A. Baney, Director of Human Resources and Safety 704-922-6485 [email protected] Isothermal Community College Rick Edwards, Director of Plant Operations and Maintenance 828-286-3636 ext. 598 [email protected] Dr. Kimberly J. Gold, Vice President of Academic and Student Services Institutional Assessment 828-286-3636 ext. 388 [email protected] Mayland Community College Dr. John Gossett, Vice President of Student Development 828-765-7351 ext. 210 [email protected] Gerald Hyde, Vice President of Administrative Services 828-765-7351 ext. -

NC DHSR HCPEC: State-Approved Nurse Aide I Training Programs

NORTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES DIVISION OF HEALTH SERVICE REGULATION HEALTH CARE PERSONNEL EDUCATION AND CREDENTIALING SECTION State-Approved Nurse Aide I Training Programs As of 11/02/2018 County/City Facility Phone / ALAMANCE/Graham Alamance Community College (336) 578-2002 ALAMANCE/Burlington Alamance Community College-Goodwill Site (336) 278-2202 ALEXANDER/Taylorsville Catawba Valley Community College - Alexander Campus (828) 327-7000 ALLEGHANY/Sparta Wilkes Community College/Alleghany Campus (336) 372-5061 ANSON/Wadesboro South Piedmont Community College - Lockhart-Taylor Cntr (704) 290-5217 ASHE/Jefferson Wilkes Community College/Ashe Campus (336) 838-6204 ASHE/West Jefferson Wilkes Community College/Ashe County HS (336) 838-6204 AVERY/Newland Mayland Community College/Avery Campus (828) 765-7351 AVERY/Newland Mayland Community College/Avery Campus (828) 733-5883 BEAUFORT/Washington Beaufort County Community College/Beaufort Campus (252) 946-6194 BERTIE/Windsor Martin Community College/Bertie Campus (252) 794-4861 BERTIE/Windsor Roanoke-Chowan Community College/Bertie HS CCP (252) 862-1261 BLADEN/Dublin Bladen Community College (910) 879-5500 BLADEN/Dublin Bladen Community College (910) 879-5632 BLADEN/Clarkton Bladen Community College - Oakdale Homes Community Bldg (910) 879-5634 BLADEN/Riegelwood Bladen Community College/East Arcadia (910) 879-5500 BRUNSWICK/Bolivia Brunswick Community College (910) 755-7337 BUNCOMBE/Weaverville Asheville Buncombe Technical Community College/NBHS (828) 398-7960 BUNCOMBE/Asheville