Oral History Transcript T-0109, Interview with Elijah Shaw And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

Schlitten, Don African & African American Studies Department

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Oral Histories Bronx African American History Project 7-13-2006 Schlitten, Don African & African American Studies Department. Don Schlitten Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_oralhist Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Schlitten, Don. Interview with the Bronx African American History Project. BAAHP Digital Archive at Fordham University. This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Bronx African American History Project at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oral Histories by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interviewer: Maxine Gordon Interviewee: Don Schlitten July 13, 2006 Page 1 Maxine Gordon (MG): This is interview 179 for the Bronx African History Project, Maxine Gordon interviewing Don Schlitten in his home in Kingsbridge, which is in the Bronx. So thank you very much, I had to put that on the interview. Are you born in the Bronx? Don Schlitten (DS): Born in the Bronx, Bronx Maternity Hospital. I’ve been in the Bronx my entire life and various places. But for 33 years I’ve always lived in the Bronx. MG: And where did you go to school? DS: In the Bronx. [laughs] P.S. 26. MG: Oh good, where’s that. DS: Junior high school eighty - - P.S. 26 was on West Bernside and West of University Avenue. It’s probably a prison now or something [laughs]. Then I went to Junior High School 82 which was on McClellan Road and Tremont Avenue. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

The Twenty Greatest Music Concerts I've Ever Seen

THE TWENTY GREATEST MUSIC CONCERTS I'VE EVER SEEN Whew, I'm done. Let me remind everyone how this worked. I would go through my Ipod in that weird Ipod alphabetical order and when I would come upon an artist that I have seen live, I would replay that concert in my head. (BTW, since this segment started I no longer even have an ipod. All my music is on my laptop and phone now.) The number you see at the end of the concert description is the number of times I have seen that artist live. If it was multiple times, I would do my best to describe the one concert that I considered to be their best. If no number appears, it means I only saw that artist once. Mind you, I have seen many artists live that I do not have a song by on my Ipod. That artist is not represented here. So although the final number of concerts I have seen came to 828 concerts (wow, 828!), the number is actually higher. And there are "bar" bands and artists (like LeCompt and Sam Butera, for example) where I have seen them perform hundreds of sets, but I counted those as "one," although I have seen Lecompt in "concert" also. Any show you see with the four stars (****) means they came damn close to being one of the Top Twenty, but they fell just short. So here's the Twenty. Enjoy and thanks so much for all of your input. And don't sue me if I have a date wrong here and there. -

View the Ancient One Play

Play The Ancient One by T.A. Barron Part One Adapted by Suzanne I. Barchers Illustrations by Heather Ballanca; Map by Anthony B.Venti Kate wanted to help her aunt stop loggers from destroying ancient redwoods. Now she’s in for a bigger adventure than she ever imagined ... 1 of 19 The Ancient One by T.A. Barron CHARACTERS (Main parts in bold face) Narrators 1, 2 Jody, a teenage boy Kate, a teenage girl Billy, a logger Aunt Melanie, Kate’s aunt Frank, Jody’s grandfather, a logger Sly, Billy’s younger brother Laioni, a native Halami girl Stones 1, 2, 3, 4 Chieftain, ruler of the Tinnanis Chieftess, wife of the Chieftain S C E N E 1 Narrator 1: Kate’s sneakers squelch as she splashes through the rain to the post office in Blade, Oregon, a small logging town. Kate is spending the summer with her aunt while her parents are on vacation. Narrator 2: When Kate scampers up the post office steps, a lean red-haired boy throws open the door, knocking Kate backward down the steps. The boy almost lands on her. Jody: Hey, watch where you’re going! Kate: Watch yourself! Narr 1: Suddenly, Kate’s eyes fall on the parcel the boy had been carrying. It is a large envelope bearing her aunt’s name. The boy snatches up the envelope and runs down the street. Kate: Hey, come back! Narr 2: Kate chases after the boy, catching up to him and knocking him to the ground. Kate: Give me that! Jody: No way! Narr 1: The envelope lands in the mud, and a large man puts his foot on it. -

Ernest Elliott

THE RECORDINGS OF ERNEST ELLIOTT An Annotated Tentative Name - Discography ELLIOTT, ‘Sticky’ Ernest: Born Booneville, Missouri, February 1893. Worked with Hank Duncan´s Band in Detroit (1919), moved to New York, worked with Johnny Dunn (1921), etc. Various recordings in the 1920s, including two sessions with Bessie Smith. With Cliff Jackson´s Trio at the Cabin Club, Astoria, New York (1940), with Sammy Stewart´s Band at Joyce´s Manor, New York (1944), in Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith´s Band (1947). Has retired from music, but continues to live in New York.” (J. Chilton, Who´s Who of Jazz) STYLISTICS Ernest Elliott seems to be a relict out of archaic jazz times. But he did not spend these early years in New Orleans or touring the South, but he became known playing in Detroit, changing over to New York in the very early 1920s. Thus, his stylistic background is completely different from all those New Orleans players, and has to be estimated in a different way. Bushell in his book “Jazz from the Beginning” says about him: “Those guys had a style of clarinet playing that´s been forgotten. Ernest Elliott had it, Jimmy O´Bryant had it, and Johnny Dodds had it.” TONE Elliott owns a strong, rather sharp, tone on the clarinet. There are instances where I feel tempted to hear Bechet-like qualities in his playing, probably mainly because of the tone. This quality might have caused Clarence Williams to use Elliott when Bechet was not available? He does not hit his notes head-on, but he approaches them with a fast upward slur or smear, and even finishes them mostly with a little downward slur/smear, making his notes to sound sour. -

Bill Holcombe's Musicians Publications Visit Our Online Store!

Bill Holcombe's Musicians Publications Visit our online store! www.billholcombe.com/store SHIP TO: P.O. Box No. : _____________ Phone: ____________Fax:_____________________________ Name: _________________________________________________________________ Street: _________________________________________________________________ City,State,Zip: ________________________________________________________________ Counry: ________________________________________________________________ Ordering Information Musicians Publications is always ready to answer your questions about our publications. Orders may be placed by phone, fax, mail or email. All orders are shipped from Chesapeake, Virginia and are billed in U.S. dollars. There is a $25 net minimum for all wholesale orders. Foreign orders will be shipped by sur- face mail unless otherwise specified. Contents: Arranging ............................2 Orchestra ............................. 52 Brass Ensembles ........ 31-43 Percussion ........................... 43 Cello .................................51 Saxophone ......................15-20 String Orchestra ................53-54 Choral ...............................55 String Quartets and Trios ....... 49, 50 Clarinet ........................11-14 Trombone ........................38-40 Concert Band .............. 44-47 Trumpet ...........................36-37 Flute .............................. 3-10 Tuba ...................................... 40 French Horn ................ 41-43 Viola ..................................51 Jazz Band .........................48 -

My Best Friend

My Best Friend Stories From the San José Public Library Adult Literacy Program 2013 194846_CSJ_Library_MyBestFriend_BW_R5.indd 1 8/21/13 11:34 AM My Best Friend Production Team Production Coordinator: Ellen Loebl Editors: Victoria Scott, Ellen Hill, and Ellen Loebl Writing Workshop: MaryLee McNeal The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the San José Public Library, the City of San José, or any other funders of the Partners in Reading program. No official endorsement by these agencies should be inferred. 194846_CSJ_Library_MyBestFriend_BW_R5.indd 2 8/21/13 11:34 AM Table of Contents Acknowledgments vii Partners in Reading Appreciates Your Continued Support viii Introduction ix Learners Stories Partners in Reading 1 by Abraham Beyene My Niece Rita 2 by Faalaa Achica I Love My Best Friend 3 by Megnaga Aimru Very Quiet and Friendly 4 by Emebet Akalewold An Ocean of Friendship 5 by Martha Arambula She Saw My First Step 6 by Johana Arizmendi My Best Friend Is My Tutor Gail 8 by Genet A. In Memory of My Best Friend Rosemary Domingues 10 by Juanita Avila My Companion Always 12 by Sonia B. All the Qualities of a Best Friend 14 by Queenie Buenaluz Carlos 16 by Daniel Cardenas We Always Had Good Communication 17 by Rosa Chavarria We Still Keep in Touch 19 by Jongwoo Choi My Faraway Friend 21 by Iye Conteh Introduction iii 194846_CSJ_Library_MyBestFriend_BW_R5.indd 3 8/21/13 11:34 AM Claudia and Me 23 by Irma Contreras He Taught Me Never to Quit 24 by Robert Jeff Coulter Building a Chicken Coop 25 by E. -

Jazzing up Jazz Band JB Dyas, Phd As Published in Downbeat Magazine

Jazzing Up Jazz Band JB Dyas, PhD As published in DownBeat magazine JB Dyas (left) works with the big band at Houston’s High School for the Performing and Visual Arts Presenting jazz workshops across the country on behalf of the Herbie Hancock Institute, it’s been my experience that too many high school jazz bands, although often sounding quite impressive, are really playing very little jazz. On any given tune, few students are able to improvise – arguably jazz’s most important element. Most of the band members don’t know the chord progression, the form, or even what a chorus is – essentials for the jazz musician. And all too often they haven’t listened to the definitive recordings – a must in learning how to perform this predominantly aural art form – or know who the key players are. They're just reading the music that’s put in front of them, certainly not what jazz is all about. What they’re doing really has little relation to this music’s sensibility; it's more like “concert band with a swing beat.” The teaching and learning of jazz can and should be an integral component of every high school jazz band rehearsal. Since most high schools don’t have the luxury of offering separate jazz theory, improvisation and history classes, jazz band needs to be a “one stop shop.” Therefore, repertoire is key, meaning the repertoire chosen for the school year and the order in which it is presented should be such that it is conducive to the learning of jazz theory and improvisation in a natural, understandable and playable unfolding of material. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

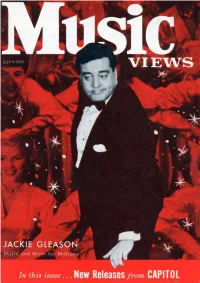

In This Issue... New Releases from CAPITOL the C O VER Music Views There Are Very Few People in July, 1955 Voi

In this issue... New Releases from CAPITOL THE C O VER Music Views There are very few people in July, 1955 Voi. XIII, No. 7 this country who have not come into contact with a TV set. There are even fewer who do not VIC ROWLAND .... Editor have access to a phonograph. Associate Editors: Merrilyn Hammond, Anyone who has a nodding ac Dorothy Lambert. quaintance with either of these appliances is sure to be fa miliar with either Jackie Gleason the comedian, Jackie Gleason GORDON R. FRASER . Publisher the musician, or both. This lat ter Jackie Gleason, the musi Published Monthly By cian, has recently succeeded in coming up with a brand new CAPITOL PUBLICATIONS, INC. sound in recorded music. It's Sunset and Vine, Hollywood 28, Calif. found in a new Capitol album, Printed in U.S.A. "Lonesome Echo." For the full story, see pages 3 to 5. Subscription $1.00 per year. A regular musical united nations is represented by lady and gentlemen pictured above. Left to right they are: Louis Serrano, music columnist for several South American magazines; Dean Martin, whose fame is international; Line Renaud, French chanteuse recently signed to Cap itol label; and Cauby Peixoto, Brazilian singer now on Columbia wax. 2 T ACKIE GLEASON has indeed provided mirth strument of lower pitch), four celli, a marim " and music to millions of people. Even in ba, four spanish-style guitars and a solo oboe. the few remaining areas where television has Gleason then selected sixteen standard tunes not as yet reached, such record albums as which he felt would lend themselves ideally "Music For Lovers Only" and other Gleason to the effect he had in mind.