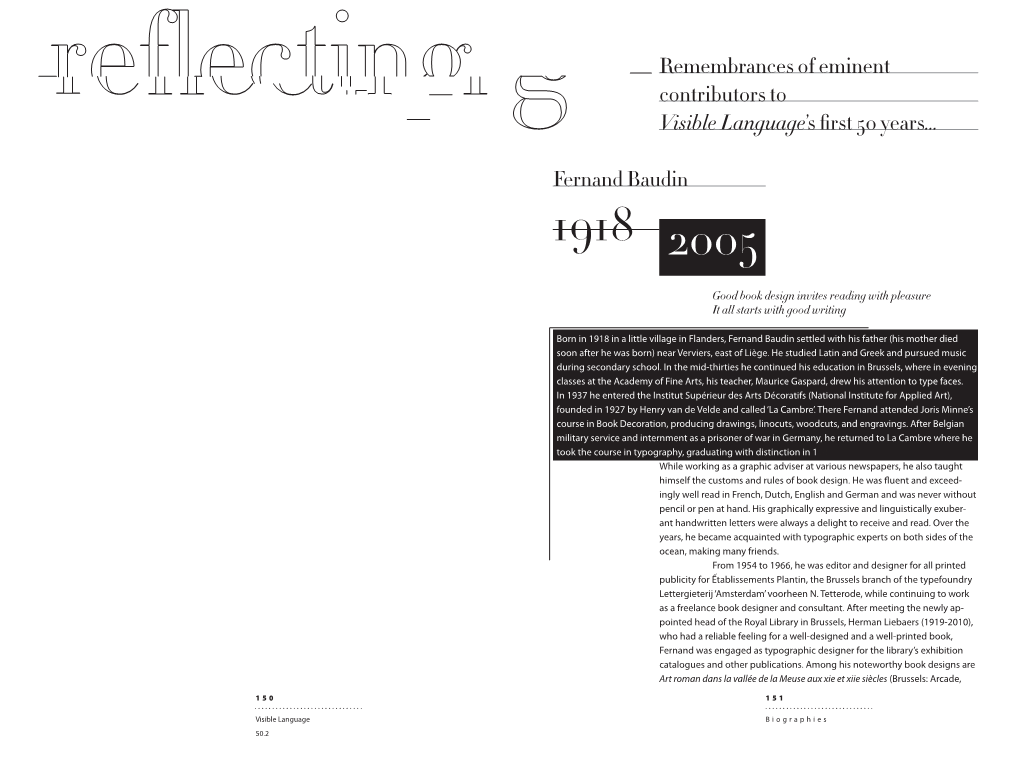

Fernand Baudin Remembrances of Eminent Contributors to Visible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Type ID and History

History and Identification of Typefaces with your host Ted Ollier Bow and Arrow Press Anatomy of a Typeface: The pieces of letterforms apex cap line serif x line ear bowl x height counter baseline link loop Axgdecender line ascender dot terminal arm stem shoulder crossbar leg decender fkjntail Anatomy of a Typeface: Design decisions Stress: Berkeley vs Century Contrast: Stempel Garamond vs Bauer Bodoni oo dd AAxx Axis: Akzidenz Grotesk, Bembo, Stempel Garmond, Meridien, Stymie Q Q Q Q Q Typeface history: Blackletter Germanic, completely pen-based forms Hamburgerfonts Alte Schwabacher c1990 Monotype Corporation Hamburgerfonts Engraver’s Old English (Textur) 1906 Morris Fuller Benton Hamburgerfonts Fette Fraktur 1850 Johan Christian Bauer Hamburgerfonts San Marco (Rotunda) 1994 Karlgeorg Hoefer, Alexei Chekulayev Typeface history: Humanist Low contrast, left axis, “penned” serifs, slanted “e”, small x-height Hamburgerfonts Berkeley Old Style 1915 Frederic Goudy Hamburgerfonts Centaur 1914 Bruce Rogers after Nicolas Jenson 1469 Hamburgerfonts Stempel Schneidler 1936 F.H.Ernst Schneidler Hamburgerfonts Adobe Jenson 1996 Robert Slimbach after Nicolas Jenson 1470 Typeface history: Old Style Medium contrast, more vertical axis, fewer “pen” flourishes Hamburgerfonts Stempel Garamond 1928 Stempel Type Foundry after Claude Garamond 1592 Hamburgerfonts Caslon 1990 Carol Twombley after William Caslon 1722 Hamburgerfonts Bembo 1929 Stanley Morison after Francesco Griffo 1495 Hamburgerfonts Janson 1955 Hermann Zapf after Miklós Tótfalusi Kis 1680 Typeface -

PDF (GJ-Thesis-Print.Pdf)

Collisional dynamics of macroscopic particles in a viscous fluid Thesis by Gustavo Joseph In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California (Defended May ) ii © Gustavo Joseph All Rights Reserved iii Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to thank Prof. Melany L. Hunt, my academic adviser during my stay at Caltech. Throughout the years she has been a source of invaluable wisdom, support, and friendship. For all her encouragement and guidance, I owe her a debt of gratitude. I am also grateful to Dr. José Roberto Zenit Camacho, from whom I learned a simple way of looking at problems in order to extract non-trivial answers. From day one to D-day, he emphasized the importance of asking more questions than I wanted answered, and of letting the answers inspire new questions. As a surrogate adviser and critical inquisitor, Prof. Christopher E. Brennen always found the time and energy to encourage me to press on. He has been an endless font of knowledge and enthusiasm. Together with the aforementioned people, Prof. John F. Brady and Prof. Guruswami Ravichandran took time to review my Ph.D. dissertation and to serve on the committee. For their time and their insightful comments I remain ever thankful. Back in I was going from door to door in the Thomas Laboratory, trying to find a glass paperweight that could be used as a thick target wall for my experiments. Prof. Paul C. Jennings had on a bookshelf a block of Zerodur—a piece of mirror from the W. -

System Profile

Steve Sample’s Power Mac G5 6/16/08 9:13 AM Hardware: Hardware Overview: Model Name: Power Mac G5 Model Identifier: PowerMac11,2 Processor Name: PowerPC G5 (1.1) Processor Speed: 2.3 GHz Number Of CPUs: 2 L2 Cache (per CPU): 1 MB Memory: 12 GB Bus Speed: 1.15 GHz Boot ROM Version: 5.2.7f1 Serial Number: G86032WBUUZ Network: Built-in Ethernet 1: Type: Ethernet Hardware: Ethernet BSD Device Name: en0 IPv4 Addresses: 192.168.1.3 IPv4: Addresses: 192.168.1.3 Configuration Method: DHCP Interface Name: en0 NetworkSignature: IPv4.Router=192.168.1.1;IPv4.RouterHardwareAddress=00:0f:b5:5b:8d:a4 Router: 192.168.1.1 Subnet Masks: 255.255.255.0 IPv6: Configuration Method: Automatic DNS: Server Addresses: 192.168.1.1 DHCP Server Responses: Domain Name Servers: 192.168.1.1 Lease Duration (seconds): 0 DHCP Message Type: 0x05 Routers: 192.168.1.1 Server Identifier: 192.168.1.1 Subnet Mask: 255.255.255.0 Proxies: Proxy Configuration Method: Manual Exclude Simple Hostnames: 0 FTP Passive Mode: Yes Auto Discovery Enabled: No Ethernet: MAC Address: 00:14:51:67:fa:04 Media Options: Full Duplex, flow-control Media Subtype: 100baseTX Built-in Ethernet 2: Type: Ethernet Hardware: Ethernet BSD Device Name: en1 IPv4 Addresses: 169.254.39.164 IPv4: Addresses: 169.254.39.164 Configuration Method: DHCP Interface Name: en1 Subnet Masks: 255.255.0.0 IPv6: Configuration Method: Automatic AppleTalk: Configuration Method: Node Default Zone: * Interface Name: en1 Network ID: 65460 Node ID: 139 Proxies: Proxy Configuration Method: Manual Exclude Simple Hostnames: 0 FTP Passive Mode: -

No. 3 Science and History Behind the Design of Lucida Charles Bigelow

204 TUGboat, Volume 39 (2018), No. 3 Science and history behind the design of Lucida Charles Bigelow & Kris Holmes 1 Introduction When desktop publishing was new and Lucida the first type family created expressly for medium and low-resolution digital rendering on computer screens and laser printers, we discussed the main design de- cisions we made in adapting typeface features to digital technology (Bigelow & Holmes, 1986). Since then, and especially since the turn of the 21st century, digital type technology has aided the study of reading and legibility by facilitating the Figure 1: Earliest known type specimen sheet (detail), development and display of typefaces for psycho- Erhard Ratdolt, 1486. Both paragraphs are set at logical and psychophysical investigations. When we approximately 9 pt, but the font in the upper one has a designed Lucida in the early 1980s, we consulted larger x-height and therefore looks bigger. (See text.) scientific studies of reading and vision, so in light of renewed interest in the field, it may be useful to say Despite such early optimism, 20th century type more about how they influenced our design thinking. designers and manufacturers continued to create The application of vision science to legibility type forms more by art and craft than by scientific analysis has long been an aspect of reading research. research. Definitions and measures of “legibility” Two of the earliest and most prominent reading often proved recalcitrant, and the printing and ty- researchers, Émile Javal in France and Edmund Burke pographic industries continued for the most part to Huey in the US, expressed optimism that scientific rely upon craft lore and traditional type aesthetics. -

Hermann Zapf Collection 1918-2019

Hermann Zapf Collection 1918-2019 53 boxes 1 rolled object Flat files Digital files The Hermann Zapf collection is a compilation of materials donated between 1983 and 2008. Processed by Nicole Pease Project Archivist 2019 RIT Cary Graphic Arts Collection Rochester Institute of Technology Rochester, New York 14623-0887 Finding Aid for the Hermann Zapf Collection, 1918-2019 Summary Information Title: Hermann Zapf collection Creator: Hermann Zapf Collection Number: CSC 135 Date: 1918-2019 (inclusive); 1940-2007 (bulk) Extent: Approx. 43 linear feet Language: Materials in this collection are in English and German. Abstract: Hermann Zapf was a German type designer, typographer, calligrapher, author, and professor. He influenced type design and modern typography, winning many awards and honors for his work. Of note is Zapf’s work with August Rosenberger, a prominent punchcutter who cut many of Zapf’s designs. Repository: RIT Cary Graphic Arts Collection, Rochester Institute of Technology Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open to researchers. Conditions Governing Access: Access to audio reels cannot be provided on site at this time; access inquiries should be made with the curator. Access to original chalk calligraphy is RESTRICTED due to the impermanence of the medium, but digital images are available. Access to lead plates and punches is at the discretion of the archivist and curator as they are fragile. Some of the digital files are restricted due to copyright law; digital files not labeled as restricted are available for access with permission from the curator or archivist. Custodial History: The Hermann Zapf collection is an artificial collection compiled from various donations. -

Sans Protection: Typeface Design and Copyright in the Twenty-First Century

Sans Protection: Typeface Design and Copyright in the Twenty-First Century By TRAVIS L. MANFREDI* If there is uncertainty or lack of clarity, it is not the fault of the letters, it is how they are put together. Yet these symbols can be transformed visually without any loss of their essential character. The changes reflect new societies, new technologies, new preferences, new functions; but within these changes the symbols are constant, always themselves.1 —Alan Bartram Introduction IT HAS BEEN THIRTY-TWO YEARS since copyright protection was explicitly withheld from typeface designs.2 Personal computers have since created both a new market for typeface designs and an easy way to copy them.3 This article examines whether the genesis of this new market coupled with other effects of the digitization of fonts4 suffi- ciently alters the rationale for denying copyright protection to type- face designs to justify an amendment to the Copyright Act. Part I of this article provides a brief history of typeface design and a primer on the basic features of typefaces. These features provide for * J.D. Candidate, University of San Francisco School of Law, 2011. 1. ALAN BARTRAM, TYPEFORMS: A HISTORY 125 (2007). 2. Eltra Corp. v. Ringer, 579 F.2d 294 (4th Cir. 1978). 3. Jacqueline D. Lipton, To © or Not to ©? Copyright and Innovation in the Digital Type- face Industry, 43 U.C. DAVIS L. REV. 143, 167–68 (2009). 4. Though the terms “font” and “typeface” are often used interchangeably, the im- portant distinction between the two is explained by Professor Lipton: -

Contemporary Processes of Text Typeface Design

Title Contemporary processes of text typeface design Type The sis URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/13455/ Dat e 2 0 1 8 Citation Harkins, Michael (2018) Contemporary processes of text typeface design. PhD thesis, University of the Arts London. Cr e a to rs Harkins, Michael Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Contemporary processes of text typeface design Michael Harkins Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Central Saint Martins University of the Arts London April 2018 This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my brother, Lee Anthony Harkins 22.01.17† and my father, Michael Harkins 11.04.17† Abstract Abstract Text typeface design can often be a lengthy and solitary endeavour on the part of the designer. An endeavour for which, there is little in terms of guidance to draw upon regarding the design processes involved. This is not only a contemporary problem but also an historical one. Examination of extant accounts that reference text typeface design aided the orientation of this research (Literature Review 2.0). This identified the lack of documented knowledge specific to the design processes involved. Identifying expert and non-expert/emic and etic (Pike 1967) perspectives within the existing literature helped account for such paucity. In relation to this, the main research question developed is: Can knowledge of text typeface design process be revealed, and if so can this be explicated theoretically? A qualitative, Grounded Theory Methodology (Glaser & Strauss 1967) was adopted (Methodology 3.0), appropriate where often a ‘topic of interest has been relatively ignored in the literature’ (Goulding 2002, p.55). -

: : S C H R I F T : T Y P O G R a F I E : G R a F I K : : : D a S 2 0 . J

::: S c h r i f t : T y p o g r a f i e : G r a f i k ::: D a s 2 0 . J a h r h u n d e r t ::: S c h r i f t : T y p o g r a f i e : G r a f i k i m 2 0 . J a h r h u n d e r t ::: und die IndustrielleAnfänge::: der WerbegrafikRevolution 1 8 9 0 – 1 9 1 0 : : : ::: S c h r i f t : T y p o g r a f i e : G r a f i k D a s 2 0 . J a h r h u n d e r t ::: Frühe Plakatkunst :::um1900:: : ::: S c h r i f t : T y p o g r a f i e : G r a f i k D a s 2 0 . J a h r h u n d e r t ::: :::1890–1914:: Art Nouveau/ J u g e n d s t i l : ::: S c h r i f t : T y p o g r a f i e : G r a f i k D a s 2 0 . J a h r h u n d e r t ::: Sachlichkeit Informative : : : 1 9 1 0 : : : ::: :::1890–1910:: : 1894 Century Lim Boyd Benton a h r h u n d e r t 1896 Cheltenham Bertram Goodhue 1898 Akzidenz Grotesk (Berthold) 2 0 . J 1900 Eckmann Otto Eckmann D a s 1901 Copperplate Frederic Goudy 1901 Auriol George Auriol G r a f i k 1907 Clearface Morris Fuller Benton : 1908 News Gothic Morris Fuller Benton g r a f i e o T y p : S c h r i f t ::: ::: S c h r i f t : T y p o g r a f i e : G r a f i k D a s 2 0 . -

Suspect in Wapiti Murder Held Without Bail

TUESDAY, AUGUST 14, 2018 108TH YEAR/ISSUE 65 SUSPECTCOUNTY COMMISSION IN WAPITI MURDER HELD WITHOUT BAIL BY CJ BAKER planned to “put an end” to a long-run- covering at West Park Hospital in Cody cedure allow judges to deny bail in first- ties a conviction could bring. Tribune Editor ning dispute with Donna Klingbeil over before being released and arrested on degree murder cases, when the death However, one of Klingbeil’s defense their assets on the night of Sunday, Aug. Thursday. Klingbeil has been charged penalty is a possibility and “the proof is attorneys, Anna Olson of Casper, dis- prosecutor argued in court on 5. Hours later, Dennis Klingbeil alleg- with first-degree murder, alleging he evident or the presumption great.” puted the prosecution’s description of Monday that authorities have edly called another family member and killed Donna Klingbeil “purposely and “The statement, ‘I shot my wife in the the case and of her client. Astrong evidence that Dennis reported that he’d shot Donna Klingbeil with premeditated malice.” head,’ that’s pretty good proof,” Skoric “The proof is not great. We have hear- Klingbeil murdered his wife, Donna in the head. Circuit Court Judge Bruce Waters argued, calling Klingbeil “an extreme say statements,” Olson argued. “This Klingbeil, at their Wapiti home. Donna Klingbeil, 75, later died of her sided with Skoric on Monday and or- danger to the community.” is a one-sided story of what happened. Park County Attorney Bryan Skoric injuries; meanwhile, Dennis Klingbeil, dered Dennis Klingbeil to be held in the He also argued that Klingbeil, who We don’t know what happened in that noted that one family member has told 76, reportedly overdosed on various Cody jail without bond pending further has “significant assets,” is a flight risk authorities that Dennis Klingbeil said he medications and spent several days re- proceedings. -

Garamond Garamond Simoncini

Garamond Garamond Simoncini Adobe Garamond Overview Garamond Monotype Garamond is the name given to a group of old-style serif typefaces named for the punch- cutter Claude Garamond (c. 1480–1561). Most Garamond Berthold of the Garamond faces are more closely related to the work of a later punch-cutter, Jean Jannon. A direct relationship between Garamond’s Garamond letterforms and contemporary type can be ITC found in the Roman versions of the typefaces Adobe Garamond, Granjon, Sabon, and Stempel Garamond Garamond. Garamond’s letterforms convey a Stempel sense of fluidity and consistency. Design & Development Claude Garamond (ca. 1480–1561) cut office of Christoph Plantin in Antwerp, In 1621, sixty years after Garamond’s death, Garamond. Their true origin was not to be types for the Parisian scholar-printer where they were used by Plantin for many the French printer Jean Jannon (1580–1635) revealed until the 1927 research of Beatrice Robert Estienne in the first part of the decades, and still exist in the Plantin- issued a specimen of typefaces that had some Warde. In the early 1900s, Jannon’s types sixteenth century, basing his romans on Moretus museum. Other Garamond characteristics similar to the Garamond were used to print a history of printing in the types cut by Francesco Griffo for punches went to the Frankfurt foundry of designs, though his letters were more France, which brought new attention to French Venetian printer Aldus Manutius in 1495. Egenolff-Berner, who issued the famous asymmetrical and irregular in slope and axis. typography and the “Garamond” types. This Garamond refined his Romans in later Egenolff-Berner specimen (also available Jannon’s types disappeared from use for about sparked the beginning of modern revivals; versions, adding his own concepts as he as pdf file, 1,3 mb) in 1592 that became an two hundred years, but were re-discovered in some based on the mistaken model from developed his skills as a punchcutter. -

Fonts & Encodings

Fonts & Encodings Yannis Haralambous To cite this version: Yannis Haralambous. Fonts & Encodings. O’Reilly, 2007, 978-0-596-10242-5. hal-02112942 HAL Id: hal-02112942 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02112942 Submitted on 27 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ,title.25934 Page iii Friday, September 7, 2007 10:44 AM Fonts & Encodings Yannis Haralambous Translated by P. Scott Horne Beijing • Cambridge • Farnham • Köln • Paris • Sebastopol • Taipei • Tokyo ,copyright.24847 Page iv Friday, September 7, 2007 10:32 AM Fonts & Encodings by Yannis Haralambous Copyright © 2007 O’Reilly Media, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472. O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (safari.oreilly.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: (800) 998-9938 or [email protected]. Printing History: September 2007: First Edition. Nutshell Handbook, the Nutshell Handbook logo, and the O’Reilly logo are registered trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. Fonts & Encodings, the image of an axis deer, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. -

Typography 2015 Natahlia Lee 1242760 Anatomy of a Typeface

TyPedia Typography 2015 Natahlia Lee 1242760 Anatomy of a Typeface Font/Typeface Italics Definition: “A font is a set of printable or displayable text characters in a specific Definition: “While roman typefaces are upright, italic typefaces slant to the right. style and size. The type design for a set of fonts is the typeface, and variations But rather than being just a slanted or tilted version of the roman face, a true or of this design form the typeface family . Thus, Helvetica is a typeface family, pure italic font is drawn from scratch and has unique features not found in the Helvetica italic is a typeface, and Helvetica italic 10-point is a font. In practice, roman face.” (Typography Deconstructed, 2010). font and typeface are often used without much precision, sometimes interchangably.” (Rouse, 2005). Example of Italics Example of Font/Typeface Italics Italics Helvetica Times new roman italics Font helvetica italic HelveticaTypeface helvetica italic 10-point Special Characters Small Caps Definition: “Special characters are any characters that are not on a standard Definition: “Small caps are short capital letters designed to blend with lowercase keyboard. They can also sometimes be know as a glyph. Special characters are text. They’re usually slightly taller than lowercase letters.” (Butterick) those that fall outside the basic alphabet of your language and can include symbols, less common punctuation, foreign characters and almost any other Example of Small Caps letterform you can imagine.” (Cousins, 2014) Example of Special Characters SMALL CAPS SMALL caps Example of the use of all Example of blending letters being small caps small caps with lower © case letters Copyright symbol ™Trade mark sign Anatomy of a Typeface Upper Case Kerning Definition: Upper case refers to capital letters.