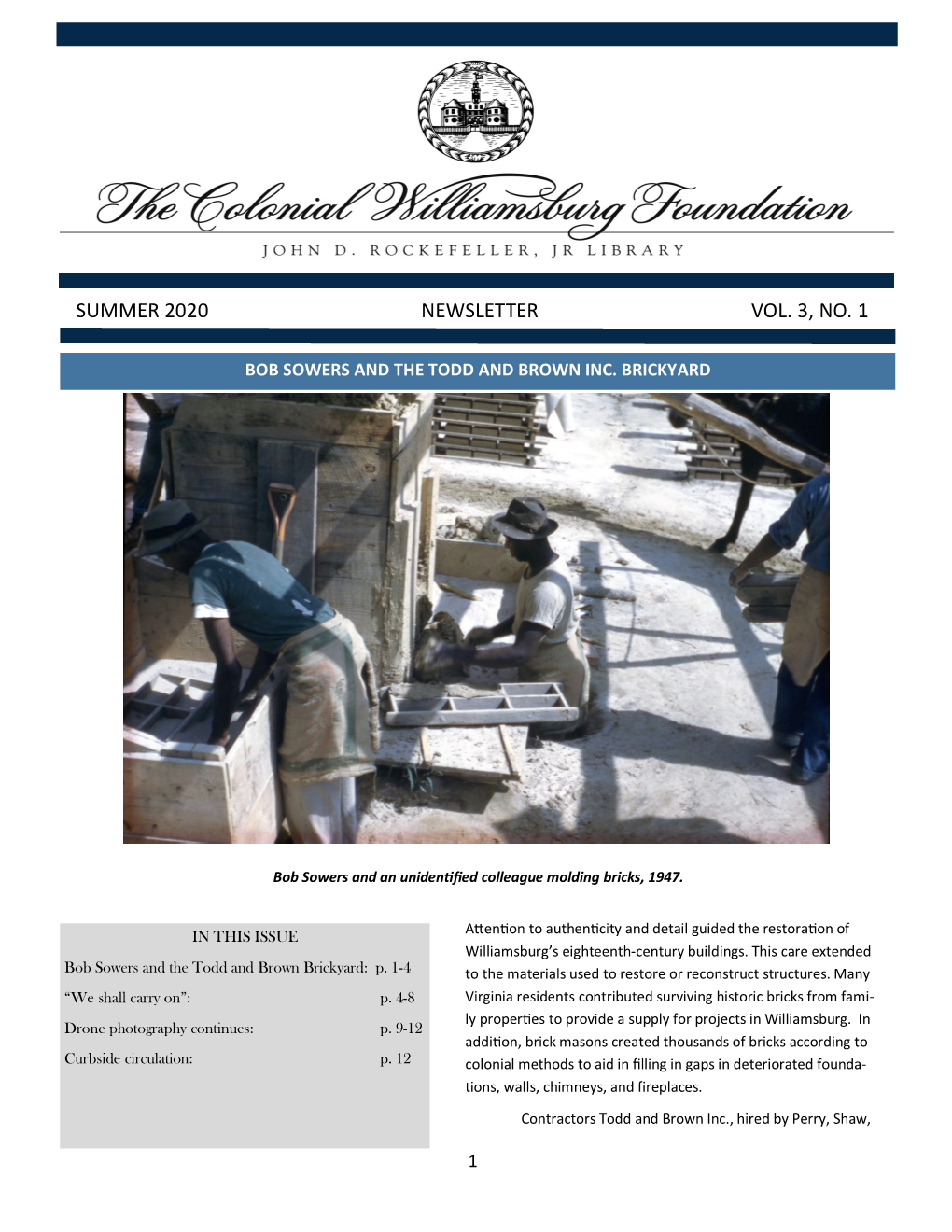

Summer 2020 Newsletter Vol. 3, No. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Williamsburg Reserve Collection Celebrating the Orgin of American Style

“So that the future may learn from the past.” — John d. rockefeller, Jr. 108 williamsburg reserve collection Celebrating the Orgin of American Style. 131109 colonial williamsburg Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg, the capital of the colony of Virginia, owed its inception to politics, its design to human ingenuity, and its prosperity to government, commerce and war. Though never larger in size than a small English country town, Virginia’s metropolis became Virginia’s center of imperial rule, transatlantic trade, enlightened ideas and genteel fashion. Williamsburg served the populace of the surrounding colonies as a marketplace for goods and services, as a legal, administrative and religious center, and as a resort for shopping,information and diversion. But the capital was also a complex urban community with its own patterns of work, family life and cultural activities. Within Williamsburg’s year round populations, a rich tapestry of personal, familial, work, social, racial, gender and cultural relationships could be found. In Williamsburg patriots such as Patrick Henry protested parliamentary taxation by asserting their right as freeborn Englishmen to be taxed only by representatives of their own choosing. When British authorities reasserted their parliamentary sovereign right to tax the King’s subjects wherever they reside, Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, James Madison, George Washington and other Virginians claimed their right to govern themselves by virtue of their honesty and the logic of common sense. Many other Americans joined these Virginians in defending their countrymen’s liberties against what they came to regard as British tyranny. They fought for and won their independence. And they then fashioned governments and institutions of self-rule, many of which guide our lives today. -

New Membership Program Offers Value and Supports the Growing Art

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation P.O. Box 1776 Williamsburg, Va. 23187-1776 www.colonialwilliamsburg.com New Membership Program Offers Value and Supports the Growing Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg Individual and family memberships offer value and benefits and support the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum “Dude,” tobacconist figure ca. 1880, museum purchase, Winthrop Rockefeller, part of the exhibition “Sidewalks to Rooftops: Outdoor Folk Art” at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum; rendering of the South Nassau Street entrance to the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg; “Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I”, artist unidentified, 1590-1600, gift of Preston Davie, part of the exhibition “British Masterworks: Ninety Years of Collecting at Colonial Williamsburg,” opening Feb. 15 at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum. WILLIAMSBURG, Va. (Feb. 5, 2019) –Colonial Williamsburg offers a new opportunity to enjoy and support its world-class art museums, the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, with annual individual and family memberships that provide guest benefits and advance both institutions’ exhibition and interpretation of America’s shared history. The DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, which showcases the best in British and American fine and decorative arts from 1670-1840, and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, home to the nation’s premier collection of American folk art, remain open during their donor-funded, $41.7-million expansion, which broke ground in 2017 and is scheduled for completion this year. Once completed, the expansion will add 65,000 square feet with a 22- percent increase in exhibition space as well as a new visitor-friendly entrance on Nassau Street. -

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations Revised Report and Documentation Prepared for: Department of Defense U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Submitted by: January 2004 Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations: Revised Report and Documentation CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary..........................................................................................iii 2.0 Introduction – Project Description................................................................. 1 3.0 Methods ................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 NatureServe Data................................................................................................ 3 3.2 DOD Installations............................................................................................... 5 3.3 Species at Risk .................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Results................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Nationwide Assessment of Species at Risk on DOD Installations..................... 8 4.2 Assessment of Species at Risk by Military Service.......................................... 13 4.3 Assessment of Species at Risk on Installations ................................................ 15 5.0 Conclusion and Management Recommendations.................................... 22 6.0 Future Directions............................................................................................. -

The Premier Luxury Destination Management Company for the U.S., Canada and the Caribbean

THE PREMIER LUXURY DESTINATION MANAGEMENT COMPANY FOR THE U.S., CANADA AND THE CARIBBEAN 2 3 CONTENTS ABOUT US Our Story 5 Why Excursionist? 7 What We Offer 7 TRAVEL STYLES Luxury Family Travel 13 Romance Travel 14 Corporate Travel 15 Educational Travel 16 Festival + Event Travel 18 TRAVEL BY PASSION Food + Drink 21 The Arts 22 People + Culture 23 Nature 24 Wellness 25 Sports + Adventure 26 THE REGIONS New England 28 New York State 32 The Mid-Atlantic 36 The South 40 Florida 44 The Southwest 48 The West 52 The Pacific Northwest 56 California 60 Alaska 64 Hawaii 68 Western Canada 72 Eastern Canada 76 The Caribbean 80 HOTELS + MAPS Hotel Collection 84 Maps 94 3 “Our mission is to empower luxury travelers — whether a couple, family, or corporate group — to live out their diverse passions through exceptional, life-changing experiences that we design and deliver.” 4 Our Story Excursionist was founded in 2010 by three friends who immigrated to North America from various corners of the world and developed a dedication to sharing this continent’s rich history, nature, cuisine and culture with others. Identifying a gap in the marketplace for a true luxury-focused destination management company for the United States, Canada and the Caribbean, we have built an organization that not only has geographical breadth across our territory, but also an intense depth of local knowledge in each destination where we work. We achieve this by bringing to bear our diverse expertise in the industry, as well as our personal relationships in the sciences, arts, education, government and business. -

NALF Fentress SSA U.S. District Court FBI Camp Peary Colonial National

Camp Peary Army Corps Naval of Engineers Weapons Station Yorktown Colonial National SSA Yorktown National Naval Station Historic Park SSA Cemetery/Battlefield Norfolk Cheatham Plum Tree Naval Support Annex USCG U.S. District Island NWR Activity Court Training Center Hampton Roads Yorktown Hampton National Camp Elmore/ Cemetery Camp Allen Ft. Monroe Maritime Administration National NATO SSA National Defense Monument VA Allied Command Reserve Fleet Medical Center Animal & Transformation Plant Health Joint Forces Inspection DEA U.S. District Staff College Service GSA Court Animal & JEB Jefferson Plant Health Little Creek-Ft Story Joint Base Laboratory Inspection Langley-Eustis Service Colonial EEOC National U.S. Customs Historic Park NASA House Veterans Langley GSA Research NOAA Marine USCG Shore Center Center Ops Center Infrastructure FBI USCG Station Jamestown GAO National Atlantic Logistics Center Little Creek Historic Site Hampton Roads Naval Museum ATF Cape Henry USCG Craney Island OPM Memorial Atlantic Area USCG Base Lafayette SSA Portsmouth River Annex Secret USCG GSA U.S. Service 5th District Navy Exchange Additional NOAA Nansemond Customs House St. Helena Command Sites and offices NWR Annex NAS Oceana Joint Staff NRTF LEGEND Animal & St. Juliens Hampton Roads Driver DEA Dept. of the Interior Plant Health Creek Annex Camp Pendleton Dept. of Agriculture Inspection Dam Neck Dept. of Defense Service DOL Area Maritime Office Annex Dept. of Homeland Security Administration Maritime Administration GSA Dept. of Justice SSA Dept. of Energy Dept. of Commerce Naval Medical Back Bay Dept. of Veterans Affairs Farm Center NWR Norfolk Naval NALF Fentress Dept. of Labor Services Portsmouth Shipyard NASA Agency Farm Prepared by: Center Great Dismal Services Naval Support Activity Swamp GSA Agency Northwest Annex Center NWR SSA Updated 11-13 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Colonial National Yorktown National Historic Park Cemetery/Battlefield Plum Tree Island NWR Ft. -

Natioflb! HISTORIC LANDMARKS Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR ^^TAT"E (Rev

THEME: ^fch:chitecture NATIOflB! HISTORIC LANDMARKS Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ^^TAT"E (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE VirjVirginia COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES James City AT; °;-' T; J"" Bil$VENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) COMMON: Carter's Grove Plantation AND/OR HISTORIC: Carter's Grove Plantation STREET AND NUMBER: Route 60, James City County CITY OR TOWN: CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT: vicinity of Williamsburg 001 COUNTY: Virginia 51 James City 095 CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District gg Building d Public Public Acquisition: K Occupied Yes: i iii . j I I Restricted Site Q Structure 18 Private || In Process LJ Unoccupied ' ' i i r> . i 6*k Unrestricted D Object D Both | | Being 'Considered D Preservation work lc* in progress ' 1 PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) 53 Agricultural [ | Government | | Park Transportation S Comments [~| Commercial I I Industrial |X[ Private Residence Q Other ....___.,, The _____________kitchen D Educotionai D Military rj Religious dependency is occupied by Mr. & D Entertainment D Museum rj Scientific Mrs. McGinley. The rest of the ' WiK«-¥.:.:jliBi.; ;ttjr: the" pub^li;^! OWNER'S NAME: Colonial Williamsburg, Inc., Carlisle H. Humelsine, President Virginia STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: CODF Williamsburg Virginia 51 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC: Clerk of the Circuit Court P.O. Box 385 CityJames STREET AND NUMBER: Court Street (2 blocks south of -

Colonial Parkway a Triple Memorial of History Is Here Made Accessible by a Scenic and Historically Rich Parkway

COLONIAL PAR KWAY IAMSB uko. 't14,4 Jamestown 0 94%cb 44, c°' 1L viRGirrit, Williamsburg Colonial National Historical Park VIRGINIA Colonial Parkway A triple memorial of history is here made accessible by a scenic and historically rich parkway N THE Virginia Peninsula three fa- Williamsburg Information Center. These mous places—Jamestown, Williams- are the best points of departure for seeing 0 burg, and Yorktown—form a triangle the areas. only 14 miles at the base. Here, between The parkway route is outward from James- the James and York Rivers, is compressed a town Island over a sandbar to Glasshouse great deal of American history. The found- Point An isthmus existed there in colonial ing of the first permanent English settlement times. For the colonists, it was the way to in 1607 at Jamestown, Va.; the establish- unoccupied lands awaiting beyond. In the ment there of the first representative form vicinity of the Glasshouse and Virginia's Fes- of government in the New World; the flower- tival Park, Colonial Parkway bends sharply ing of colonial culture and growth of revolu- to cross Powhatan Creek and then courses tionary sentiment at Williamsburg; and the eastward along Back River and the Thor- winning of American independence at York- oughfare, which separate Jamestown Island town are historical milestones. from the mainland. After following the Each place has a thrilling story of its own. James River for 3 miles, the parkway at Yet, they are connected stories, for things College Creek turns inland through the woods that happened at Jamestown led directly to toward Williamsburg. -

Regional Map

REGIONAL MAP N e w K e n t G ll o u c e s t e r ñðò11 James City County, Williamsburg, York County York Chesapeake River Bay ¤£17 (!30 (!30 15 ñðò 5 n CAMP PEARY Æc 4 2 R ! O CHA MBE AU D R 64 RD ND § O ¨¦ M ICH R Y K P E 60 IN S D L 60 R ¤£ E D M ON U ¤£ H M ICH R 25 199 5 1 8 E R 5 ! OCH (! AM B ^ n EAU ^ DR CHEATHAM 3 ñðò 31 3 "11 n ANNEX 4 ^ 2^ " ^ USCG 9 ST " LLARD ñ 3 BA TRAINING C 6 O 3 O ! K CENTER 19 R ^ D YORKTOWN 64 ñðò 2 ¨¦§ v® 17 2 17 ¤£ GOO 15 SLEY RD 173 ñðò n !n6 (! G 238 E O 3 R (! G 19 E ¹º W RIC A H S G n M O H O ND I O R N D D G W 143 CHEATHAM T O IN 3 N ! M N ( E ANNEX EM C O K n R R YORKTOWN IA D 6 L H NAVAL ñðò WY D 21 WEAPONS R G 610 R ñðò U n 14 9 STATION B Æc 1 (! S M 1 Poquoson C A 132 A I 11 River 614 P L " ñðò I n L ! T I ( O W ñðò (! L L D A L 14 2 N 10 2 O 3 D " 4 1 " I N 16 E Y G n T K ^ R P U 64 J a m e s D O J a m e s R 17 7 R ñðò ¨¦§ E T ¤£ N 5 E " ñðò C ii t y C H U S 10 M 8 I EL U ! S Q IN 30 E R P n A 620 K 8 W M " Y Y P o q u o s o n K (! P o q u o s o n W n P n SEC E ON D ST N P I A S R 60 G L IC E 4 E n H M M RD S ! U £ T O S ¤ H 13 S 24 ND PA 1 R BY 16 27 D R E ñðò ^ Æc ñðò A n M Y ñðò n n P 199 5 W YO G K R ! E ñðò K S O T P 1 (! 64 R M " 105 G E ER E N R 13 I IM ¨¦§ W A S (! A C S L 1 TR H E v® L IN PO 173 M C n G N AHO T U N D TAS V O H H 6 23 TRL L (! N 12 E B M 17 6 N 9 E ! R IS " " M 171 Y T O n S R S ñðò E Æc U IA T (! ñðò E L V A T H R W O O Y W L F Y L 7 D 2 E V T ! L H C 3 I B E 29 T 14 C N H 2 1 G n R O ñ M I ER E M RI B ^ MAC E TR N n ¹º L E K D R 60 64 D 1 ¤£ 7 2 1 26 ×× ¨¦§ D LV -

Over 55 Years Ago, the United States Entered World War II. to Most Americans, Now, It’S Something That Happened “Over There” and Is Far Removed from Home

by Mike Prero Over 55 years ago, the United States entered World War II. To most Americans, now, it’s something that happened “over there” and is far removed from home. We frequently read books and see movies about our soldiers in Japanese or German prisoner-of-war camps, but few members of the younger generation realize that between 1942 and 1946, the United States held almost 400,000 German, more than 50,000 Italian, and 5,000 Japanese soldiers in P.O.W. camps right here in the United States. I’ve been a Military collector ever since I entered the hobby, but my interest was really drawn to P.O.W. camps during a game of bridge a number of years ago. Our opponents, an elderly couple, had actually met and fallen in love in a Japanese P.O.W. camp in the Philippines. Fascinating! And so are P.O.W. camp covers. There were over 500 such P.O.W. camps in America during the war. One of them was right down the road from here, in Stockton, CA. Not surprisingly, most were located in the western and central states that had wide-open spaces: California, Texas, Idaho, Arizona, Nebraska, Kansas, Wyoming, etc. Although, there were a few in places like Maryland, Wisconsin, and Michigan. As with most World War II U.S. installations, there are a variety of covers from these P.O.W. camps, although they are definitely scarce compared to the number of camps that existed. I currently have 6,842 U.S. Military covers, but Major P.O.W. -

Tuesday, April 25, 2017 10 A.M. to 5 P.M

224 Tuesday, April 25, 2017 Williamsburg10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Photo courtesy of Nina Mustard Homes on this nine-property tour span in age from the beginning of the 18th century to a 21st century Colonial Revival. All are conveniently concentrated in two neighborhoods located near each other. Visitors will appreciate interiors that sparkle with floral designs by the Williamsburg Garden Club complementing spectacular antiques and artwork. Not to be outdone, the gardens of featured properties are prime examples of 18th century to current landscaping styles and include a city farm garden, shade gardens, a school garden, as well as formal and cottage gardens that represent the Williamsburg style. This year’s tour features five private properties in the College Terrace neighborhood that are opened for the first time for Historic Garden Week in addition to Historic Area properties and gardens - a full day of touring with 11 sites total. Start at the William and Mary Alumni house, which serves as tour headquarters, and walk or use the tour shuttle, included in the ticket. Enjoy lunch at the many establishments in Merchant’s Square and Colonial Williamsburg. Hosted by The Williamsburg Garden Club Chairmen Tickets: $50 pp. Cash/Check/Credit Card Dollie Marshall and Linda Wenger accepted at the following locations. Tick- [email protected] ets available at the Colonial Williamsburg Visitors Center on Monday, April 24, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., and on Tuesday, April 25, 9 Advance and Tour Bus Ticket Sales Chairman a.m. until noon. Tickets are also available on tour day beginning at 9:30 a.m. -

Bulletin of the College of William and Mary in Virginia

c ii.A^ .-\^ -¥- Vol. 34, No. 3 BULLETIN March, 1940 of The College of William and Mary IN Virginia CATALOGUE of W^t College of l^illiam anb iMarp in Virginia Two Hundred and Forty-Seventh Yeah 1959-mo Announcements , Session 1940-1941 WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA 1940 Entered at the post office at Williamsburg, Virginia, July 3, 1926, under act of August 24, 1912, as second-class matter Issued January, February, March, April, June, August, November Entered at the post office at Williamsburg, Virginia, July 3, 1926, under act of August 24, 1912, as second-class matter Issued January, February, March, April, June, August, November Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/bulletinofcolleg343coll Wren Building—East Front Showing Lord Botetourt's Statue Vol. 34, No. 3 BULLETIN March, 1940 of The College of William and Mary IN Virginia CATALOGUE W^t College of William anb iHarp in Two Hundred and Forty-Seventh Year 1939-1940 Announcements i Session 1940-1941 WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA 1940 Entered at the post office at Williamsburg, Virginia, July 3, 1926, under act of August 24, 1912, as second-class matter Issued January, February, March, April, June, August, November CONTENTS Page Calendar 4 College Calendar 5 Board of Visitors 6 Standing Committees of the Board of Visitors 7 OflScers of Administration 8 Officers of Instruction 9 Standing Committees of the Faculty 18 Special Lecturers 21 Alumni Association 22 Societies and Publications 24 Athletics for Men 26 -

Colonial Williamsburg to Resume Limited Onsite Programming June 14

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation P.O. Box 1776 Williamsburg, Va. 23187-1776 colonialwilliamsburg.org Colonial Williamsburg to Resume Limited Onsite Programming June 14 Select sites to reopen at reduced capacity, changes to guest experience; face coverings and social distancing required for staff and guests inside foundation-owned buildings Colonial Williamsburg will resume limited public programming at select sites on June 14. This first wave of openings is based on Virginia’s move into Phase 2 of the state’s Forward Virginia initiative. The foundation will open additional sites and expand programming in coming weeks and months pending government and public health guidance to further limit health risks associated with COVID-19. “We are eager to welcome employees and guests back to Colonial Williamsburg, but re- opening our public sites requires that we work together so that we all remain safe,” said President and CEO Cliff Fleet. “Our phased re-opening plan is based on state guidelines and is fully supported by our regional partners. With this plan in place, we can move at a measured pace toward our shared goal of a return to normal operations.” The following Colonial Williamsburg indoor and open-air sites will operate at reduced capacity and follow site-specific safety guidelines developed as part of the foundation’s COVID-19 business resumption plan, which is consistent with the state’s Phase 2 requirements: • The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg • Governor’s Palace • Capitol • Courthouse • Weaver trade shop • Carpenter’s Yard • Peyton Randolph Yard • Colonial Garden • Magazine Yard • Armoury Yard • Brickyard • George Wythe Yard • Custis Square, including tours The Williamsburg Lodge is currently open with additional hospitality operations expanding based on sustainable business demand.