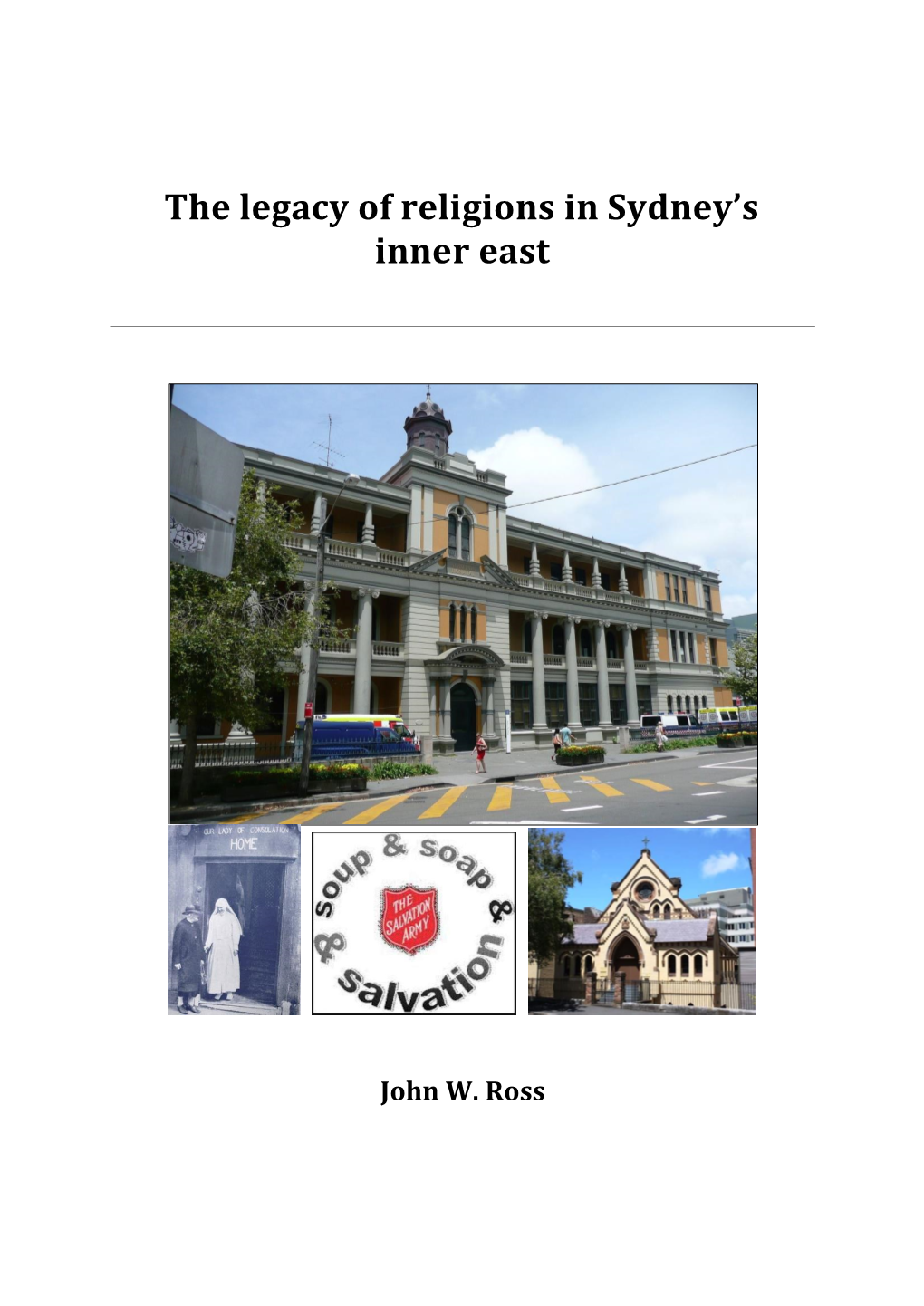

The Legacy of Religions in Sydney's Inner East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUIP Itinerary

Itinerary for PSU SOVA 2021 Social and Cultural Explorations in the Visual Arts: in Sydney, Australia 13 July 2021 - 24 July 2021 Tuesday 13 July Day 1: Sydney 8:50 AM Group flight arrives 9:30 AM Welcome to Sydney Your guide for today’s walking tour will greet you upon arrival at the airport with a sign that reads "PENN STATE UNIVERSITY." Please meet at Exit A at the northern end of the terminal. If you miss your flight and will be arriving late, please contact your faculty leader, Dr. Angela Rothrock (Phone: 011 61 420 675 797 or Email: [email protected]), to let her know when you will be arriving. You will then be responsible for making your own way from the airport to the accommodation. Please notify your family of your safe arrival. 10:15 AM Depart by coach to Travelodge Sydney (travel time approximately 30 minutes) Please store your luggage at Travelodge Sydney. You will be able to check in after 3:30 PM. Please notify hotel staff of any valuables (laptop computers, jewellery, electronics, etc.) and they can lock them in a secure room for you. 11:10 AM Depart by coach to The Rocks historic neighborhood (travel time approximately 20 minutes) 11:30 AM Guided walking tour of The Rocks Your guide will provide you with a detailed history of The Rocks as you visit sites of interest in the area. Topics include Aboriginal history and culture, Australia’s history as a convict penal colony, the start of European migration to Australia and Sydney landmarks. -

METHODIST PIONEERS in the SOUTH PACIFIC by Rev

METHODIST PIONEERS IN THE SOUTH PACIFIC By Rev. Dr F. Baker The first chaplain appointed to New South Wales in 1786 was a Methodist in the secondary sense of being a devout evangelical clergyman, and was deliberately sponsored as such by William Wilberforce, friend and admirer of the Wesleys. The second who arrived under Wilberforce's auspices, Samuel Marsden (1765-1838),1 was similar in spirituality, but much tougher both in spirit and in body. His Methodism was even nearer to that of Wesley, for he had been born into a Yorkshire Wesleyan family. and apparently became one of their lay preachers.2 He was educated for the Anglican ministry at the expense of the Elland Clerical Society, an evangelical group founded in 1767 by Wesley's friend the Rev. Henry Venn, vicar of Huddersfield.3 By them he was sent to Hull Grammar School (aged 23!) and then on to Magdalene College. Cambridge, where he was befriended by Rev. Charles Simeon, after whom he named one of his children.4 The dire straits of the Chaplain in New South Wales, however, undoubtedly stressed by Governor Phillip in person as well as by Johnson himself in letters, made Wilberforce and his friends extremely anxious to secure another evangelical candidate as quickly as possible. Therefore they exerted pressure on Marsden, even to the extent of persuading him to leave Cambridge without graduating. His agreement was a measure of his Christian dedication, and also proof that they had indeed chosen the right man, eminently qualified by spiritual gifts, by robust strength, and by practical training. -

Agentname Contactperson Email Address Wise Vision Aiden Parker [email protected]

AgentName ContactPerson Email Address Wise Vision Aiden Parker [email protected]. Suite 610,368 Sussex street, Sydney, NSW, Australia 2000 au 2 Easy Travel Carolina [email protected] 200 Mary street, BRISBANE ADELAIDE STREET, QLD, Australia 4000 Maffezzolli m 360 Degree Agency Mara Marquez [email protected] 133 Castlereagh St, Sydney, NSW, Australia 2000 cy 4 U Australia Lobsang Caviedes Contact@4uaustralia. unit 25/6 White Ibis drive, GRIFFIN, QLD, Australia 4503 com 51 Visas Pty Ltd Terry [email protected] Level 24, 300 Barangoo Ave, SYDNEY, NSW, Australia 2000 om A Block Company Barhodirova [email protected] 1/2 Labzar str, Tashzent, Tashzent, Uzbekistan 00000 Dilrabo ABC International Services Andrea Juarez [email protected] Level 9, office 46, 88 Pitt Street, SYDNEY, NSW, Australia 2000 PTY LTD m.br ABC Student Center Arthur Harris [email protected] Suite 303 / 468 George st, Sydney, NSW, Australia 2000 .au ABK Consultancy Bhawani Poudel bhawani.poudel@abkl Suite 33, Level 3, 110 Sussex Street, SYDNEY, NSW, Australia 2000 awyers.com.au Abroad Australia Leidy Patino admin@abroadaustral 20-22 princes highway, WOLLI CREEK, NSW, Australia 2205 ia.com Active Migration Education James McNess amelia@activemigrati 2/32 Buckingham Drive, Wanggara, WA, Australia 6065 oneducation.com.au AECC Global Missy Matsuda clientrelations@aeccgl Ground Floor, 20 Queen Street, MELBOURNE, VIC, Australia 3000 obal.com Agape Student Service Stefannie Costa scosta@agapestudent Suite 2, level 14 309 Kent street, Sydney, NSW, Australia 2000 .com.au -

Interchange Access Plan – Central Station October 2020 Version 22 Issue Purpose: Sydney Metro Website – CSSI Coa E92 Approved Version Contents

Interchange Access Plan – Central Station October 2020 Version 22 Issue Purpose: Sydney Metro Website – CSSI CoA E92 Approved Version Contents 1.0 Introduction .................................................1 7.0 Central Station - interchange and 1.1 Sydney Metro .........................................................................1 transfer requirements overview ................ 20 1.2 Sydney Metro City & Southwest objectives ..............1 7.1 Walking interchange and transfer requirements ...21 1.3 Interchange Access Plan ..................................................1 7.2 Cycling interchange and transfer requirements ..28 1.4 Purpose of Plan ...................................................................1 7.3 Train interchange and transfer requirements ...... 29 7.4 Light rail interchange and transfer 2.0 Interchange and transfer planning .......2 requirements ........................................................................... 34 2.1 Customer-centred design ............................................... 2 7.5 Bus interchange and transfer requirements ........ 36 2.2 Sydney Metro customer principles............................. 2 7.6 Coach interchange and transfer requirements ... 38 2.3 An integrated customer journey .................................3 7.7 Vehicle drop-off interchange and 2.4 Interchange functionality and role .............................3 transfer requirements ..........................................................40 2.5 Modal hierarchy .................................................................4 -

Property Portfolio June 2007 Contents

PROPERTY PORTFOLIO JUNE 2007 CONTENTS INVESTMENT PORTFOLIO Commercial Summary Table 6 NSW 8 VIC 12 Industrial Summary Table 6 NSW 14 VIC 20 QLD 26 SA 30 WA 31 DEVELOPMENT PORTFOLIO Residential NSW 33 VIC 37 QLD 41 WA 44 Commercial & Industrial NSW 48 VIC 51 QLD 54 SA/WA 56 2 AUSTRALAND PROPERTY PORTFOLIO JUNE 2007 3 Dear reader, It is with pleasure that Australand provides this Property Portfolio update for the 2007 year. Since the 2006 report, Australand has had a busy year with our pipeline of residential, commercial and industrial development properties growing strongly. Recent highlights included: • Launch of the first stage of our Port Coogee development in Western Australia, an 87 ha development on the Cockburn coast consisting of a 300 pen marina, marina lots, apartments, residential lots and a large commercial precinct. • Our total pipeline of Commercial and Industrial projects increasing to over $1bn, the launch of our sixth wholesale property fund whilst our Investment Property portfolio has grown to over $1.5bn. • In Sydney, construction of the fifth office tower within the Rhodes Corporate Park along with the second stage of the highly successful Freshwater Place commercial tower at Southbank in Melbourne. Details of these and many other new and existing development projects continue to enhance Australand’s reputation as a premier fully-integrated property developer. As announced recently, Australand will shortly be welcoming Bob Johnston as its new Managing Director. Bob will join Australand in August this year. At the same time the Group has farewelled Brendan Crotty who for 17 years as Managing Director has guided Australand from a $300m market capitalised residential developer to a $2bn plus fully diversified property business. -

NSWBC Agent List As at 2020-8-1

Sydney College - Agent list Agency legal Name Agency Name Address Contact Name Suite 301 Level 3, 363 -367 Pitt Street, Sydney, NSW 2000 Tel: +61 2 9290 1647 3BEES GROUP PTY LTD 3Bees Education & Migration TIRTHA KHATIWADA Email: [email protected] Website: 3beesgroup.com.au Ground Floor 38 College Street, Darlinghurst, NSW 2010 Tel: +61 2 9380 9888 AUSTRALIAN CENTRE PTY LTD AUSTRALIAN CENTRE Natalia TJONG Email: [email protected] Website: australian.co.th Suite 710/ 368 Sussex St., Sydney NSW 2000 Tel: +61 2 8540 7103 BIGDAY EDUCATION PTY LTD Bigday Education Rosini Chandra Email: [email protected] Website: www.bigdayeducation.com Level 2, Suite 45, 181 Church Street, Parramatta NSW 2150 OZ PACIFIC GROUP PTY LTD Oz Pacific GroupTel: +61 4 2969 3474 Jaypee Casapao Email: [email protected] Website: www.ozpacificgroup.com.au suite 35/301 Castlereagh St, Sydney NSW 2000 CONNECTION STUDENT PTY LIMITED CONNECTION STUDENT Tel: +61 2 9211 7770 DANIEL DANTE MARON Email: [email protected] Website: www.connectionstudent.com Suite 605, Level 6, 405-411 Sussex Street, Sydney NSW 2000 Joe Kent DK Science & Learning International Student COROS INTERNATIONAL PTY LTD Tel. +61 2 9264 4566 Centre Email: [email protected] website: www.dksydney.com.au Level 20, Tower 2 Darling Park, 201 Sussex Street, Sydney NSW 2000 Tel: +61 433 122 170 or +61 2 8074 3578 EDUNETWORK PTY LTD Edunetwork Australia Brian Quang H Dinh Email: [email protected] Website: edunetwork.net.au Suite 903, level 9, 307 Pitt street, Sydney NSW 2000 FIRST ONE EDUCATION PTY LTD First One Education Migration Tel: +61 2 92670718 Kevin White Email: [email protected] Website: firstedumigration.com.au Suite 302/683 George St, Haymarket NSW 2000 FUSION OZ PTY. -

Women in Colonial Commerce 1817-1820: the Window of Understanding Provided by the Bank of New South Wales Ledger and Minute Books

WOMEN IN COLONIAL COMMERCE 1817-1820: THE WINDOW OF UNDERSTANDING PROVIDED BY THE BANK OF NEW SOUTH WALES LEDGER AND MINUTE BOOKS Leanne Johns A thesis presented for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the Australian National University, Canberra August 2001 DECLARATION I certify that this thesis is my own work. To the best of my knowledge and belief it does not contain any material previously published or written by another person where due reference is not made in the text. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge a huge debt of gratitude to my principal supervisor, Professor Russell Craig, for his inspiration and encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis. He gave insightful and expert advice, reassurance when I needed it most, and above all, never lost faith in me. Few supervisors can have been so generous with their time and so unfailing in their support. I also thank sincerely Professor Simon Ville and Dr. Sarah Jenkins for their measured and sage advice. It always came at the right point in the thesis and often helped me through a difficult patch. Westpac Historical Services archivists were extremely positive and supportive of my task. I am grateful to them for the assistance they so generously gave and for allowing me to peruse and handle their priceless treasures. This thesis would not have been possible without their cooperation. To my family, who were ever enthusiastic about my project and who always encouraged and championed me, I offer my thanks and my love. Finally, this thesis is dedicated to the thousands of colonial women who endured privations, sufferings and loneliness with indomitable courage. -

Transactions in Review

1 April 2013 – 30 April 2013 TRANSACTIONS IN EVIEW R August 2017 ABOUT THIS REPORT Inside this Issue Sales Preston Rowe Paterson prepare standard research reports covering the main markets within which we operate in each of our capital cities and major Commercial Page 2 regional locations. Industrial Page 3 The markets covered in this research report include the commercial office Retail Page 4 market, industrial market, retail market, specialized property market, hotel and Residential Page 4 leisure market, residential market and significant property fund activities. Residential Development Page 5 We regularly undertake valuations of commercial, retail, industrial, hotel and Rural Page 6 leisure, residential and special purpose properties for many varied reasons, as Specialised Properties Page 6 set out later herein. Hotel and Leisure Page 7 We also provide property management services, asset and facilities management services for commercial, retail, industrial property as well as plant Leasing and machinery valuation. Commercial Page 7 Industrial Page 8 Retail Page 9 Specialised Properties Page 9 Property Funds & Capital Raisings Page 9 About Preston Rowe Page 10 Paterson Contact Us Page 12 Phone: +61 2 9292 7400 Fax: +61 2 9292 7404 Address: Level 14, 347 Kent Street Sydney NSW 2000 Email: [email protected] Follow us: Visit www.prp.com.au © Copyright Preston Rowe Paterson Australasia Pty Limited Page | 1 SALES 417 St Kilda Road, Melbourne, VIC 3004 Commercial Mapletree Investments has bought the A-grade office tower for $145 million on a sub. 6% yield. The property has 20,441 m2 of lettable 165 Moggill Road, Taringa, QLD 4068 area over 10-levels. -

Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 Under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979

2012 No 628 New South Wales Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 I, the Minister for Planning and Infrastructure, pursuant to section 33A of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979, adopt the mandatory provisions of the Standard Instrument (Local Environmental Plans) Order 2006 and prescribe matters required or permitted by that Order so as to make a local environmental plan as follows. (S07/01049) SAM HADDAD As delegate for the Minister for Planning and Infrastructure Published LW 14 December 2012 Page 1 2012 No 628 Sydney Local Environmental Plan 2012 Contents Page Part 1 Preliminary 1.1 Name of Plan 6 1.1AA Commencement 6 1.2 Aims of Plan 6 1.3 Land to which Plan applies 7 1.4 Definitions 7 1.5 Notes 7 1.6 Consent authority 7 1.7 Maps 7 1.8 Repeal of planning instruments applying to land 8 1.8A Savings provision relating to development applications 8 1.9 Application of SEPPs 9 1.9A Suspension of covenants, agreements and instruments 9 Part 2 Permitted or prohibited development 2.1 Land use zones 11 2.2 Zoning of land to which Plan applies 11 2.3 Zone objectives and Land Use Table 11 2.4 Unzoned land 12 2.5 Additional permitted uses for particular land 13 2.6 Subdivision—consent requirements 13 2.7 Demolition requires development consent 13 2.8 Temporary use of land 13 Land Use Table 14 Part 3 Exempt and complying development 3.1 Exempt development 27 3.2 Complying development 28 3.3 Environmentally sensitive areas excluded 29 Part 4 Principal development standards -

685S Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

685S bus time schedule & line map 685S Sydney Secondary College, Blackwattle Bay View In Website Mode Campus to City Martin Place The 685S bus line Sydney Secondary College, Blackwattle Bay Campus to City Martin Place has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) City Martin Place: 3:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 685S bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 685S bus arriving. Direction: City Martin Place 685S bus Time Schedule 12 stops City Martin Place Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Sydney Secondary College Blackwattle Bay Campus, Taylor St Tuesday 3:10 PM 2-40 Taylor Street, Glebe Wednesday Not Operational Glebe Point Rd at St Johns Rd Thursday 3:10 PM 185 St Johns Road, Glebe Friday 3:30 PM Glebe Point Rd at Mitchell St 115 Glebe Point Road, Glebe Saturday Not Operational Glebe Point Rd opp Glebe Public School 61 Glebe Point Road, Ultimo Glebe Point Rd at Broadway 685S bus Info 263 Broadway, Ultimo Direction: City Martin Place Stops: 12 Broadway Shopping Centre, Broadway Trip Duration: 23 min 181 Broadway, Ultimo Line Summary: Sydney Secondary College Blackwattle Bay Campus, Taylor St, Glebe Point Rd University Of Technology Sydney, Broadway at St Johns Rd, Glebe Point Rd at Mitchell St, Glebe 20-24 Broadway, Ultimo Point Rd opp Glebe Public School, Glebe Point Rd at Broadway, Broadway Shopping Centre, Broadway, Central Station, Railway Square, Stand J University Of Technology Sydney, Broadway, Central 815 george street, Haymarket Station, Railway Square, Stand J, Hay St opp Belmore Park, Museum Station, Downing Centre, Hay St opp Belmore Park Stand E, Sheraton Grand Sydney Hyde Park, Martin 323 Castlereagh Street, Surry Hills Place Station, Elizabeth St, Stand C Museum Station, Downing Centre, Stand E 86-90 Goulburn Street, Surry Hills Sheraton Grand Sydney Hyde Park 181 Elizabeth Street, Sydney Martin Place Station, Elizabeth St, Stand C 9-19 Elizabeth Street, Sydney 685S bus time schedules and route maps are available in an o«ine PDF at moovitapp.com. -

PR8022 C5B3 1984.Pdf

'PR C60d.a.. •CS�� lq81t- � '"' �r,;,�{ cJ c::_,.:;;J ; �· .;:,'t\� -- -- - - -- -2-fT7UU \�1\\�l\1�\\�1\l�l\\\\\ I 930171 3\ �.\ 3 4067 00 4 ' PR8022. C5B3198 D e CENG __ - Qv1.1T'n on Pn-oU.t::t!. C 5831984 MAIN GEN 04/04/85 THE UNIVERSI'IY OF QUEENSlAND LIBRARIES Death Is A Good Solution THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND PRESS SCHOLARS' LIBRARY Death Is A Good Solution The Convict Experience in Early Australia A.W. Baker University of Queensland Press First published 1984 by University of Queensland Press Box 42, St Lucia, Queensland, AustraW. ©A.W.Bakerl984 This book is copyright. Aput &om my fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher. Typeset by University of Queensland Press Printed in Hong Kong by Silex Enterprise & Printing Co. Distributed in the UK, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and the Caribbe1n by Prentice Hall International, International Book DistnOutors Ltd, 66 Wood Lane End, Heme! Hempstead, Herts., England Distributed in the USA and Canada by Technical lmpex Corporation, 5 South Union Street, Lawrence, Mass. 01843 USA Cataloauing ia Publication Data Nt�tiorralLibraryoJAustrtJ!ia Baker, A.W. (Anthony William), 1936- Death is a good solution. Bibliography. .. ---· ---- ��· -�No -L' oRAR'V Includes index. � OF C\ :��,t;�,�k'f· I. Aumalim litera�- History mdl>AAI�. � �· 2. Convicts in literature. I. Title (Series: University of Queensland Press scholars' library). A820.9'3520692 LibrtJryofCortgrtss Baker, A.W.(Anthony William), 1936- Death is a good solution. -

Society and Political Controversies in New South Wales

The Politics of Grievance: society and political controversies in New South Wales 1819— 1827 Michael Charles Connor BA (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Tasmania, December 2002. i AUTHORITY OF ACCESS This thesis may be available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. ii This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award or for any other degree or diploma in any tertiary institution. To the best of the candidate's knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text of the thesis. & C., (..,e,",■r-----* iii For Margaret Alison De Long f iv CONTENTS Abstract p.vii Abbreviations p.x Introduction p.1 PART ONE: Vocabulary and Society p.7 Chapter One p.8 Exclusionists and confusionists Chapter Two p.22 Colonial society — rank and inequality PART TWO: Dividing society 1819— 1821 P.+4 Chapter Three p.45 Constitutional rights and limitations Chapter Four p.69 Bullock v. Dodd in New South Wales PART THREE: Governor Brisbane's legacy of division — 1825 p.87 Chapter Five p.88 Newspapers and authorship Chapter Six p.112 The beginning of the Dinnerist Crisis Chapter Seven p.126 Personal vituperation and constitutional reform Chapter Eight p.143 The Governor's Dinner PART FOUR: Governor Darling's Sydney 1825 —1826 p.162 Chapter Nine p.163 Expectations and the reality Chapter Ten p.181 Family and government Chapter Eleven p.193 Calls for violence and heavier chains PART FIVE: The Sudds-Thompson Case in 1826 — 1827 p.206 Chapter Twelve p.207 Political friendships Chapter Thirteen p.223 A Parade Ground ceremony Chapter Fourteen p.252 The Case begins Chapter Fifteen p.275 Political tensions, threatened impeachment Chapter Sixteen p.302 Personal grievances and imperial arguments PART SIX: Conclusion — The Lessons of Chronology p.332 Chapter Seventeen p.333 Chronology and grievance APPENDICES p.342 Appendix One p.343 Act No.