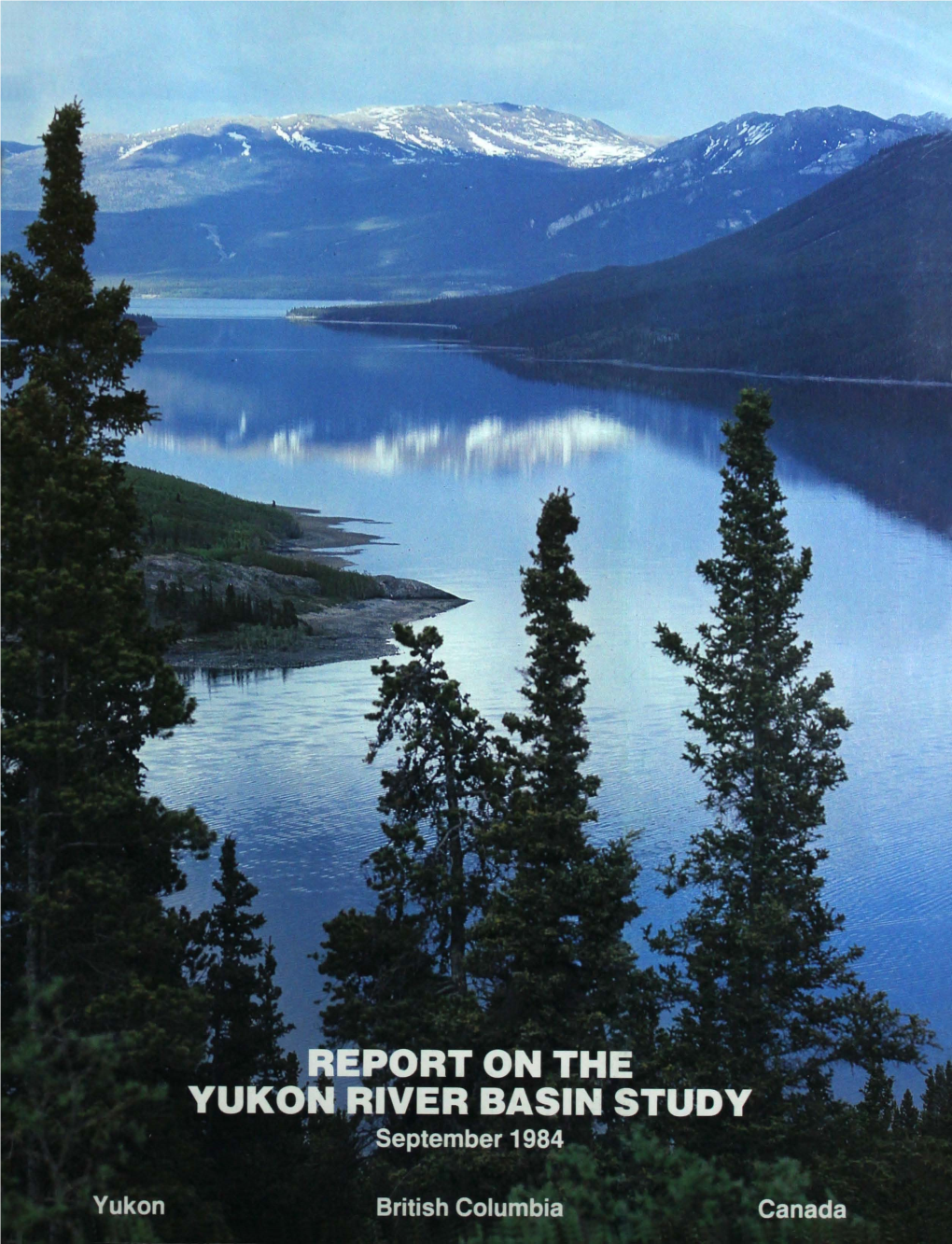

REPORT on the YUKON RIVER BASIN STUDY September 1984

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve – Foundation Statement

Yukon - Charley Rivers National Preserve National Park Service Alaska Department of the interior Yukon - Charley Rivers National Preserve FOUNDATION STATEMENT Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve Foundation Statement (draft) 1 Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve Foundation Statement July, 2012 Prepared By: Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve National Park Service, Alaska Regional Office National Park Service, Denver Service Center Table of Contents Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve – Foundation Statement Elements of a Foundation Statement…2 Establishment of Alaska National Parks…3 Summary Purpose Statement…4 Significance Statements…4 Location Regional Maps…5 Preserve Map…6 Purpose Statement…7 Significance Statements / Fundamental Resources and Values / Interpretive Themes 1. Charley River…8 2. Wildlife Populations and Habitat…9 3. Geology and Paleontology…10 4. History and Archeology…11 5. Human Use…12 Special Mandates and Administrative Commitments…13 Participants…14 Appendix A – Legislation Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act – Selected Excerpts…15 Appendix B – Legislative History Proclamation 4612 – Yukon-Charley National Monument, 1978…25 Foundation Statement Page 1 Elements of a Foundation Statement The Foundation Statement is a formal description of Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve’s core mission. It is a foundation to support planning and management of the preserve. The foundation is grounded in the preserve’s legislation and from knowledge acquired since the preserve was originally established. It provides a shared understanding of what is most important about the preserve. This Foundation Statement describes the preserve’s purpose, significance, fundamental resources and values, primary interpretive themes, and special mandates. The legislation that created Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve guides the staff in understanding and documenting why Congress and the president created the preserve. -

Human Ecological Dimensions of Change in the Yukon River Basin: a Case Study of the Koyukon Athabascan Village of Ruby, Ak

HUMAN ECOLOGICAL DIMENSIONS OF CHANGE IN THE YUKON RIVER BASIN: A CASE STUDY OF THE KOYUKON ATHABASCAN VILLAGE OF RUBY, AK A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science by Nicole Joy Wilson May 2012 © 2012 Nicole Joy Wilson ABSTRACT Although the three papers that comprise this thesis analyze distinct problems they are all rooted in the study of human ecology. To that end they are based on the same data set and share the same goals. Participatory research methods involving semi-structured interviews with twenty community experts, seasonal rounds and human ecological mapping are employed to analyze the subsistence livelihoods of the Koykon Athapaskan people of Ruby Village as a manifestation of human ecological relations. Chapter 1 examines the contribution of indigenous knowledge to understandings of hydrologic change in the Yukon River and its tributaries including observations of alterations in sediment and river ice regimes. Chapter 2 considers the ethical dimensions of adaptation and vulnerability to climate change in indigenous communities who are situated within a political context influenced by a history of colonization. Chapter 3 seeks to develop a concept of water sovereignty that addresses the complex socio-cultural and ecological relations between indigenous peoples and water. The integrated perspective provided by this thesis illustrates the connections between indigenous knowledge, subsistence livelihoods, socio-cultural and ecological relations to water and the assertion of sovereignty in the face of global change. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Nicole Wilson grew-up in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in Calgary, AB. -

A Listing of Pacific Coast Spawning Streams and Hatcheries

A LISTING OF PACIFIC COAST SPAWNING STREAMS AND HATCHERIES PRODUCING CHINOOK AND COHO SALMON with Estimates on Numbers of Spawners and Data on Hatchery Releases 1/ Roy J. Wahle and Roger E. Pearson2/ 1/Pacific Marine Fisheries Commission 2000 S.W. First Avenue Metro Center, Suite 170 Portland, OR 97201-5346 Present address: 8721 N.E. Blackburn Road Yamhill, OR 97148 2/(Co-author deceased) Northwest and Alaska Fisheries Center National Marine Fisheries Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 2725 Montlake Boulevard East Seattle, WA 98112 September 1987 This document is available to the public through: National Technical Information Service U.S. Department of Commerce 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 iii ABSTRACT Information on chinook, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha, and coho, O. kisutch, salmon spawning streams and hatcheries along the west coast of North America was compiled following extensive consultations with fishery managers and biologists and thorough review of published and unpublished information. Included are a listing of all spawning streams known as of 1984-85, estimates of the annual number of spawners observed in the streams, and data on the annual production of juvenile chinook and coho salmon at all hatcheries. Streams with natural spawning populations of chinook salmon range from Mapsorak Creek, 18 miles south of Cape Thompson, Alaska, southward to the San Joaquin River of California's Central Valley. The total number of spawners is estimated at 1,258,135. Streams with coho salmon range from the Kukpuk River, 12 miles northeast of the village of Point Hope, Alaska, southward to the San Lorenzo River in the Monterey Ray region of California. -

The Yukon River and Bering Sea

Title The Land-Sea Interactions Related to Ecosystems : The Yukon River and Bering Sea Author(s) Chikita, Kaz A.; Okada, Kazuki; Kim, Yongwon; Wada, Tomoyuki; Kudo, Isao Edited by Hisatake Okada, Shunsuke F. Mawatari, Noriyuki Suzuki, Pitambar Gautam. ISBN: 978-4-9903990-0-9, 207- Citation 213 Issue Date 2008 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/38467 Type proceedings Note International Symposium, "The Origin and Evolution of Natural Diversity". 1‒5 October 2007. Sapporo, Japan. File Information p207-213-origin08.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP The Land-Sea Interactions Related to Ecosystems: The Yukon River and Bering Sea Kaz A. Chikita1,*, Kazuki Okada2, Yongwon Kim3, Tomoyuki Wada2 and Isao Kudo4 1Faculty of Science, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, 060-0810, Japan 2Graduate School of Science, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, 060-0810, Japan 3International Arctic Research Center, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, Alaska, 99775-7340, U.S.A. 4Faculty of Fisheries Sciences, Hokkaido University, Hakodate, 041-8611, Japan ABSTRACT For salmon’s going up, the Yukon River in Alaska is known to be the longest river in the world. In order to explore the effects of mass and heat fluxes of the river on the ecosystem in the Bering Sea, discharge, turbidity and water temperature were monitored in the middle and downstream reaches in 2006 to 2007. Results obtained reveal that both the river water temperature and sus- pended sediment concentration varied hysteretically in response to glacier-melt discharge or rain- fall runoffs. Runoff analysis for the time series of discharge indicates that the Yukon river discharge is occupied by the 16.9% glacier-melt discharge. -

Yukon Mining &Geology Week

Yukon Mining &Geology Week MAY 31 – JUNE 4, 2021 activity Guide DISCOVERY SPONSOR: Partners & Sponsors presented in partnershiP: DISCOVERY SPONSOR: EXPLORER SPONSORS: PROSPECTOR SPONSORS: STAMPEDER SPONSORS: Yukon Mining &Geology Week MAY 31 – JUNE 4, 2021 2 Celebrating 125th Anniversary: Klondike Gold Rush Discovery Yukon Mining & Geology Week 2021 will take place from May 31 to June 4. This year is a special one as we commemorate and celebrate the 125th anniversary of the discovery of gold in the Klondike. Since that time, Yukon has built a mining history that has contributed to the territory’s diverse and inclusive culture, thriving economy, and a globally leading quality of life. Shaw Tláa (Kate Carmack) Gumboot mother Klondike Discoverer – Yukon Gold Rush 1896 INDUCTEE 2019 Share on Social: #KateDidIt Enter ONE or ALL completed activities on Facebook @YukonMining 100+ YEARS OF YUKON WOMEN IN MINING #YMGW2021 #Explore125Au to Kate Carmack’s induction, and the acknowledgement be entered into a draw for prizes of her role alongside the Klondike Discoverers in the from Yukon businesses Mining Hall of Fame, recognizes the untold and artists! contributions of all women in the mining industry. VIRTURAL YUKON MINING ACTIVITY BOOK Download this fun-for-all-ages activity book at: Yukonwim.ca/vym/vym-activities Yukon Mining &Geology Week MAY 31 – JUNE 4, 2021 3 OPEN TO ALL YUKONERS! Yukon Rocks & Walks Scavenger Hunt SPONSORED BY: DEADLINE TO POST: JUNE 11 Tag Us!” Tag @YukonMining & add #Explore125Au How it Works: #YMGW2021 1 Use the Scavenger Hunt Site Guide with the checklist and clues 2 Safely explore in your backyard, community and across the territory (Remember the Safe 6 + 1) 3 Photo op with your discovery and post: a. -

Journal of Occurrences at the Forks of the Lewes and Pelly Rivers May 1848 to September 1852

Heritage Branch Government of the Yukon Occasional Papers in Yukon History No. 2 JOURNAL OF OCCURRENCES AT THE FORKS OF THE LEWES AND PELLY RIVERS MAY 1848 TO SEPTEMBER 1852 The Daily Journal Kept at the Hudson’s Bay Company Trading Post Known as Fort Selkirk at the Confluence of the Yukon and Pelly Rivers, Yukon Territory by Robert Campbell (Clerk of the Company) and James G. Stewart (Asst. Clerk) Transcribed and edited with notes by Llewellyn R. Johnson and Dominique Legros Yukon Tourism Heritage Branch Sue Edelman, Minister 2000 i ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface...................................................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................... vi Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... viii Authorship of the Post Journal ...................................................................................................... viii Provenance .................................................................................................................................…... x Robert Campbell and James Green Stewart: A Brief Look at Their Lives ......................…… xiii Editor’s Notes on Changes to Original Manuscript ...........................................................…… xiv Journal of Occurrences at the Forks -

Mountains, Plateaus and Basins

5/5/2017 DATES TO REMEMBER Regional Landscape Studies NORTHLANDS <<<For each region: NORTHEAST COAST Until May 26: Course evaluation period. 1. Know its physical MEGALOPOLIS Check your Hunter e-mail for instructions. geography. Smartphone: www.hunter.cuny.edu/mobilete Computer: www.hunter.cuny.edu/te CANADA’S NATIONAL CORE May 12: Last day to hand in REQUIRED ROADTRIP AMERICA’S HEARTLAND 2. Identify its unique EXERCISE without late penalty. APPALACHIA and the OZARKS characteristics. THE SOUTH 3. Be able to explain the May 16: Last class lecture and last day for GREAT PLAINS and PRAIRES human imprint. pre-approved extra credit (paper or other project). MOUNTAINS, PLATEAUS May 23: Exam III: The Final Exam and BASINS: The Empty 4. Discuss its sequence – From 9 to 11 AM << note different time from class Interior occupancy and eco- nomic development. – Same format as exams I and II. DESERT SOUTHWEST NORTH PACIFIC COAST – Last day to hand in Exam III extra credit exercise and HAWAII “Landscape Analysis” extra credit option. 2 See Ch. 2, Mountains, Plateaus 8, 10 and 15 in American and Basins Landscapes Regional Landscapes of the Visual landscape is dominated United States and Canada by physical features with rugged natural beauty but few people. Long, narrow region with Mountains, Plateaus great variations in landform (geology) and climate (latitude). and Basins: . Extends from Alaska’s North Slope to the Mexican border Different scale The Empty Interior and from the Great Plains to than main map the Pacific mountain system. Prof. Anthony Grande ©AFG 2017 V e r y W i d e through Alaska Narrow in Canada See Ch. -

Yukon River Basin Study Project Report

YUKON RIVER BASIN STUDY PROJECT REPORT: WILDLIFE NO. 1 FURBEARER INVENTORY, HABITAT ASSESSMENT AND TRAPPER UTILIZATION OF THE YUKON RIVER BASIN B.G. Slough and R.H. Jessup Wildlife Management Branch Yukon Department of Renewable Resources Box 2703 Whitehorse, Yukon Y1A 2C6 January 1984 i This report was funded by the Yukon River Basin Committee (jointly with Yukon Department of Renewable Resources) under the terms of "An Agreement Respecting Studies and Planning of Water Resources in the Yukon River Basin" between Canada, British Columbia and Yukon. The views, conclusions and recommendations are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Yukon River Basin Committee or the Government of Canada, British Columbia and Yukon. ii ABSTRACT The Yukon Department of Renewable Resources conducted furbearer inventory studies in the Canadian Yukon River Basin in 1982 and 1983. Field studies included beaver (Castor canadensis) food cache and colony site surveys, winter track-count sampling and muskrat (Ondatra zibethica) pushup surveys. Data from the surveys were analyzed in conjunction with ongoing trapper questionnaire and historical fur harvest data sources to characterize furbearer population distributions, levels, trends and habitats. Historical and present fur harvest and trapping activity are described. The fur resource capability and problems and issues associated with impacts on furbearer populations, habitats and user groups are discussed. The populations of wolves Canis lupus, red fox Vulpes fulva, coyote .Q..:.. latrans, red squirre 1 Tamiasciurus hudsonicus, wease 1 Mustela erminea, marten Martes americana, mink Mustela vison, otter Lutra canadensis, wolverine Gulo luscus, beaver, muskrat and lynx Lynx canadensis are all widely distributed within the Yukon River Basin. -

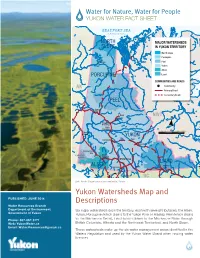

Yukon Watersheds Map and Descriptions

Water for Nature, Water for People YUKON WATER FACT SHEET Left: North Slope tundra and wetlands, Yukon Yukon Watersheds Map and PUBLISHED: JUNE 2014 Descriptions Water Resources Branch Department of Environment Six major watersheds drain the territory, each with several tributaries: the Alsek, Government of Yukon Yukon, Porcupine (which drains to the Yukon River in Alaska), Peel (which drains to the Mackenzie Delta), Liard (which drains to the Mackenzie Basin through Phone: 867-667-3171 Web: YukonWater.ca British Columbia, Alberta and the Northwest Territories), and North Slope. Email: [email protected] These watersheds make up the six water management areas identified in the Waters Regulation and used by the Yukon Water Board when issuing water licences. 1 Water for Nature, Water for People YUKON WATER FACT SHEET City of Whitehorse, and Yukon River Yukon River Basin (including the Alsek River Basin Porcupine River Basin) The Alsek River drains the southwestern portion of the Yukon to the Pacific Ocean. It is classified as a The Yukon River Headwaters contains the Southern Canadian Heritage River because of its significant Lakes region of Yukon and Northern British Columbia; natural resources: massive ice fields, high mountain there are glaciers throughout the mountains of these peaks, unique geologic history, coastal and interior headwaters. The Teslin River joins the Yukon River plant communities, significant grizzly bear population, north of Lake Laberge, contributing water mainly from and diverse bird species. snowmelt runoff in the upper portions of the basin. The Pelly and Stewart Rivers drain the eastern portion of the drainage, including mountainous terrain. -

Composition of Placer and Lode Gold As an Exploration Tool in the Stewart River Map Area, Western Yukon

Composition of placer and lode gold as an exploration tool in the Stewart River map area, western Yukon Matthew R. Dumula and James K. Mortensen1 University of British Columbia2 Dumula, M.R. and Mortensen, J.K., 2002. Composition of placer and lode gold as an exploration tool in the Stewart River map area, western Yukon. In: Yukon Exploration and Geology 2001, D.S. Emond, L.H. Weston and L.L. Lewis (eds.), Exploration and Geological Services Division, Yukon Region, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, p. 87-102. ABSTRACT A reconnaissance study of the composition of gold from several placer streams in the Stewart River map area was carried out to characterize the likely style(s) of lode mineralization from which the placer gold in each stream was derived. Results of the study indicate that placer gold from Eureka and Black Hills creeks, as well as gold grains from colluvium in exploration pits at the head of Eureka Creek, have relatively low fi neness, low copper contents and high mercury contents. These compositions are consistent with both the gold in colluvium and most of the placer gold having been derived from epithermal sources in the Eureka Dome or Henderson Dome area. Gold in placers in the Moosehorn Range is likely derived from intrusion-related, gold-bearing quartz veins exposed in the headwaters of the placer creeks, and is characterized by relatively high fi neness, high copper contents and low mercury contents. Placer gold in Thistle, Kirkman and Blueberry creeks is very similar to that from streams in the Moosehorn Range, suggesting that an undiscovered intrusion- related gold deposit is present within the Thistle/Kirkman drainage basin. -

Water Quality Objective Monitoring, Yukon River North , 2009

Water Quality Objective Monitoring, Yukon River North , 2009 Hydrologic and Geomorphic Characteristics of the Yukon River North Watershed The Yukon River is a major watercourse of north western North America. Over half of the river lies in the U.S. state of Alaska, with most of the other portion lying in and giving its name to Canada's Yukon Territory, and a small part of the river starts near the rivers source in British Columbia. The river is 3,700 km long and empties into the Bering Sea at the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. The average flow is 6,430 m³/s. The total drainage area is 832,700 km² of which 323,800 km² is in Canada. By comparison, the total area is more than 25% larger than the province of Alberta. The Yukon River is divided into two sections, the North Yukon section, downstream from the Yukon Rivers confluence with the White River and the South Yukon, the section of the Yukon River upstream from its confluence with the White River. The average water quality of the North Yukon River is much more turbid and higher in suspended solids concentrations than that of the South Yukon due to the huge contribution of sediment and glacial material entering the Yukon River from the White River drainage. Total suspended solids concentrations in the North Yukon can be 10-25 times higher than those found in the South Yukon. Many large tributary rivers and streams flow into the catchment area of the Yukon River basin. In 2009, 18 grab samples were taken by inspection staff on behalf of the Water Quality Team at 19 different locations in the Yukon River North basin. -

Stock Identification of Yukon River Chinook and Chum Salmon Using Microsatellites

Stock Identification of Yukon River Chinook and Chum Salmon using Microsatellites Report to Yukon River Panel : Project CRE 79-13 Terry D. Beacham and John Candy Pacific Biological Station Department of Fisheries and Oceans 3190 Hammond Bay Road Nanaimo, B. C. V9T 6N7 Phone: 250 756-7149 Fax: 756-7053 Email: [email protected] ii Abstract Stock identification of chum and Chinook salmon migrating past the Eagle, Alaska sonar site near the Yukon-Alaska border was conducted in 2013 through analysis of microsatellite variation. Variation at 14 microsatellites was surveyed for 891 chum salmon and variation at 15 microsatellites was surveyed for 294 Chinook salmon collected from the sonar site. For chum and Chinook salmon, all fish sampled at the Eagle sonar site were analyzed. The analysis of chum salmon samples indicated that spawning populations from the White River drainage were estimated to comprise 49% of the fish sampled that migrated past the sonar site, while approximately 51% were estimated to have been from mainstem Yukon River chum salmon spawning populations. The analysis of Chinook salmon migrating past the Eagle sonar site that were sampled indicated that the major regional stocks contributing to the run were the mainstem Yukon River (29%), Teslin River (26%), Carmacks area tributaries (18%), Pelly River (11%), upper Yukon tributaries (7%), Stewart River (5%), White River (3%), and lower Yukon tributaries (1%). iii Acknowledgments Financial support for the project was provided by the Yukon River Restoration and Enhancement Fund as well as the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT II ACKNOWLEDGMENTS III INTRODUCTION 1 MATERIALS AND METHODS 3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 6 1.0 CHUM SALMON 6 2.0 CHINOOK SALMON 6 LITERATURE CITED 7 LIST OF TABLES Table 1.