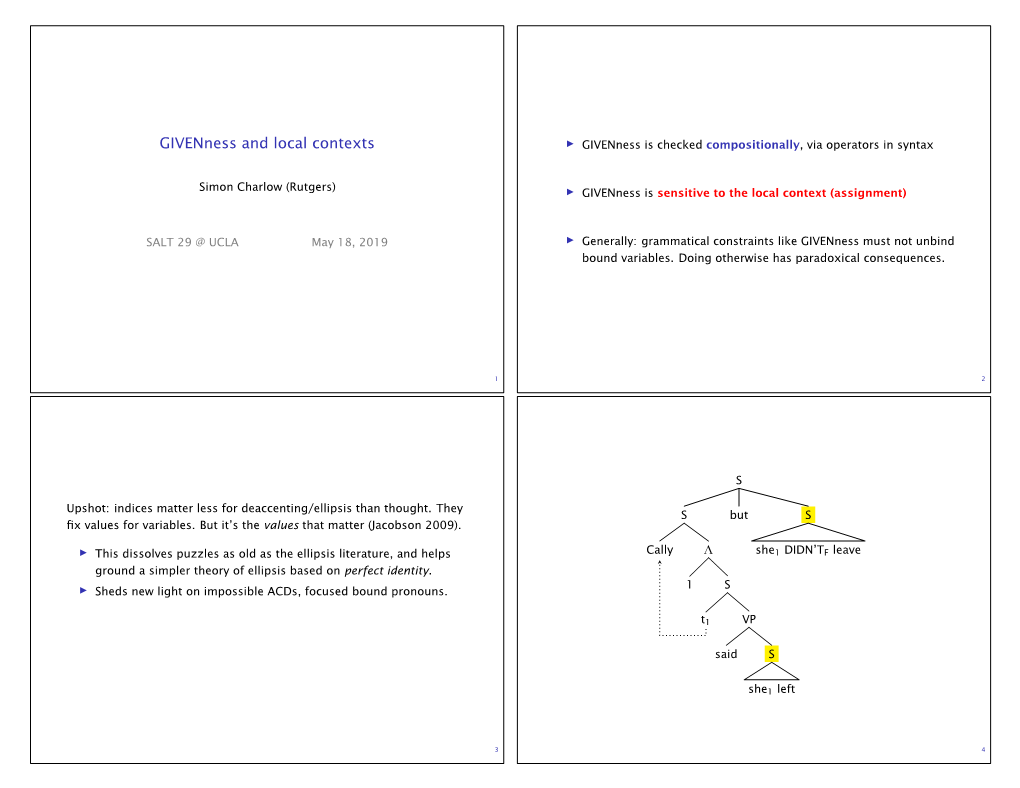

Givenness and Local Contexts Ò Givenness Is Checked Compositionally, Via Operators in Syntax

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Phenomenological Self-Givenness to the Notion of Spiritual Freedom IRIS HENNIGFELD

PhænEx 13, no. 2 (Winter 2020): 38-51 © 2020 Iris Hennigfeld From Phenomenological Self-Givenness to the Notion of Spiritual Freedom IRIS HENNIGFELD The program of the phenomenological movement, “Back to the things themselves!” does not point to any particular topic of phenomenological investigation, for example the question of being (ontology) or the question of God (metaphysics). Rather, it designates a specific methodological approach toward the things, and, as its final aim, toward a particular mode in which the things are given in experience. One particular mode in which the things are given with full evidence and in original intuition is “self-givenness”. In the experience of self-givenness, the object is fully present, or, in Edmund Husserl’s words, given in “originary presentive intuition” (Husserl, Ideas I 44, cf. 36). The correlative act on the part of the subject, the noesis, is a “seeing” which is not restricted to the senses but must be understood “in the universal sense as an originally presentive consciousness of any kind whatever” (Husserl, Ideas I 36). Self-givenness also represents the criterion of evidence and truth. The phenomenological principles of givenness and self-givenness can be made fruitful in particular for a description and investigation of those phenomena which, according to their very nature, resist other theoretical approaches. Such more “resilient” phenomena include interpersonal, religious or aesthetic experiences. Presentation becomes, in accordance with philosophical tradition, the dominant model in phenomenological research. But first-person experience shows that presentation is not the only mode of givenness and self-givenness. Rather, pushing phenomenology to its limits, the full range of experience shows that there are certain kinds of phenomena of which the genuine mode of givenness cannot be reduced to the way in which objects are presented to a subject. -

Givenness and Its Realization in a Linguistic and in a Non- Linguistic Environment

VILNIUS PEDAGOGICAL UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PHILOLOGY NATALIJA ZACHAROVA GIVENNESS AND ITS REALIZATION IN A LINGUISTIC AND IN A NON- LINGUISTIC ENVIRONMENT MA Paper Academic advisor: prof. Dr. Hab. Laimutis Valeika Vilnius, 2008 VILNIUS PEDAGOGICAL UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PHILOLOGY GIVENNESS AND ITS REALIZATION IN A LINGUISTIC AND IN A NON- LINGUISTIC ENVIRONMENT This MA paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of the MA in English Philology By Natalija Zacharova I declare that this study is my own and does not contain any unacknowledged work from any source. (Signature) (Date) Academic advisor: prof. Dr. Hab. Laimutis Valeika (Signature) (Date) Vilnius, 2008 2 CONTENTS ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………….4 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………...5 1. THE PROBLEMS OF THE INFORMATIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE SENTENCE ……………………………………………………………….8 1.1. The sentence as dialectical entity of given and new……………………...8 1.2. Givenness vs. Newnness………………………………………………….11 1.3. The realization of Givenness……………………………………………..12 1.4. Givenness expressed by the definite article ……………………………..15 1.5. Givenness expressed by the indefinite article…………………………….19 1.6. Givenness expressed by semi-grammatical definite determiners and lexical determiners………………………………………………………..20 2. THE REALIZATION OF GIVENNESS IN A LINGUISTIC ENVIRONMENT……………………………………………………………………21 2.1. Anaphoric Givenness………………………………………………………22 2.2. Cataphoric Givenness……………………………………………………...29 2.3. Givenness expressed by the use of the indefinite article…………………..30 3. THE REALIZATION OF GIVENNESS IN A NON- LINGUISTIC ENVIRONMENT……………………………………………………………………..32 3. 1. The environment of the home……………………………………………...33 3.2. The environment of the town/country, world………………………………35 3.3. The environment of the universe…………………………………………....37 3.4. Cultural environment……………………………………………………….38 4. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Syntax & Information Structure: The Grammar of English Inversions Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2sv7q1pm Author Samko, Bern Publication Date 2016 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ SYNTAX & INFORMATION STRUCTURE: THE GRAMMAR OF ENGLISH INVERSIONS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LINGUISTICS by Bern Samko June 2016 The Dissertation of Bern Samko is approved: Professor Jim McCloskey, chair Associate Professor Pranav Anand Associate Professor Line Mikkelsen Assistant Professor Maziar Toosarvandani Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Bern Samko 2016 Contents Acknowledgments x 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Thequestions ............................... 1 1.1.1 Summaryofresults ........................ 2 1.2 Syntax................................... 6 1.3 InformationStructure . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 7 1.3.1 Topic ............................... 8 1.3.2 Focus ............................... 11 1.3.3 Givenness............................. 13 1.3.4 The distinctness of information structural notions . ....... 14 1.3.5 TheQUD ............................. 17 1.4 The relationship between syntax and information structure ....... 19 1.5 Thephenomena .............................. 25 1.5.1 -

Focus and Givenness: a Unified Approach Michael Wagner Mcgill University

1 Focus and Givenness: A Unified Approach Michael Wagner McGill University Abstract Theories about information structure differ in treating focus-, contrast-, and givenness-marking as either a single phenomenon or as distinct phenomena. This paper argues for a unified approach, following the lead of Schwarzschild (1999), but a unified approach based on local alternatives (Wagner, 2005, 2006b).1 The basic insights of the local alternatives approach are captured using a new formalization, which aims to fix several problems in the original proposal noted in B¨uring (2008). The unified approach is compared with alternative approaches that invoke separate mechanisms for givenness and focus: the disanaphora approach (Williams, 1997), the F-Projection account (Selkirk, 1984, 1995), and the reference set approach in Szendr¨oi (2001) and Reinhart (2006). All of these have fundamental problems, and the requisite revisions render them equivalent to the local alternatives approach. Keywords: alternatives, focus, givenness, prosody, contrast, information struc- ture 1 The label ‘local alternatives’ for the ‘relative giveneness’ account in Wagner (2005, 2006b) was proposed in Rooth (2007) and seems like a more appropriate term. 2 Michael Wagner 1.1 Three Phenomena, or Two, or One? The distribution of accents in a sentence in English is affected by informa- tion structure in a systematic way. Information structure comprises a broad set of phenomena. This paper looks at three types of effects that influence the prosody of a sentence, those of question-answer congruence, contrast, and givenness, and presents evidence—some new, some already presented in Wag- ner (2005, 2006b)—that all three should be treated as reflexes of the same underlying phenomenon. -

BORE ASPECTS OP MODERN GREEK SYLTAX by Athanaaios Kakouriotis a Thesis Submitted Fox 1 the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Of

BORE ASPECTS OP MODERN GREEK SYLTAX by Athanaaios Kakouriotis A thesis submitted fox1 the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 1979 ProQuest Number: 10731354 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731354 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 II Abstract The present thesis aims to describe some aspects of Mod Greek syntax.It contains an introduction and five chapters. The introduction states the purpose for writing this thesis and points out the fact that it is a data-oriented rather, chan a theory-^oriented work. Chapter one deals with the word order in Mod Greek. The main conclusion drawn from this chapter is that, given the re latively rich system of inflexions of Mod Greek,there is a freedom of word order in this language;an attempt is made to account for this phenomenon in terms of the thematic structure. of the sentence and PSP theory. The second chapter examines the clitics;special attention is paid to clitic objects and some problems concerning their syntactic relations .to the rest of the sentence are pointed out;the chapter ends with the tentative suggestion that cli tics might be taken care of by the morphologichi component of the grammar• Chapter three deals with complementation;this a vast area of study and-for this reason the analysis is confined to 'oti1, 'na* and'pu' complement clauses; Object Raising, Verb Raising and Extraposition are also discussed in this chapter. -

Definiteness in Languages with and Without Articles

Definiteness in languages with and without articles Jingting Ye & Laura Becker Fudan University & Leipzig University 13th Conference on Typology and Grammar for Young Scholars 24.11.2016 ILS RAN, St Petersburg Jingting Ye & Laura Becker Definiteness and articles 1 / 49 1 Introduction 2 (In)definiteness and specificity 3 Outline: A pilot study based on multiple parallel movie subtitles 4 Results Comparing the use of articles Examples Factor strength based on random forests Other strategies to mark (in)definiteness Demonstratives Adnominal indefinites The numeral one Word order The levels of givenness Relevant factors for definiteness Trees Random forests 5 Concluding remarks Jingting Ye & Laura Becker Definiteness and articles 2 / 49 Introduction Introduction There are many accounts for definiteness, however, most rely on language-specific expressions, e.g. definite articles. Although comparative studies exist, no empirically based cross-linguistic study seems to be available yet that makes expressions of definiteness comparable directly. This pilot study explores the possibilities of parallel texts for comparing the expression of definiteness in languages with and without articles. The languages we examined are German, Hungarian, Russian, and Chinese. Jingting Ye & Laura Becker Definiteness and articles 3 / 49 (In)definiteness and specificity Definiteness Definiteness has been associated with the following concepts: uniqueness (Frege 1892; Strawson 1950; Heim & Kratzer 1998; Stanley & Gendler Szabó 2000) familiarity (Heim 1988; Roberts 2003; Chierchia 1995) -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Heterogeneity and uniformity in the evidential domain Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/40m5f2f1 Author Korotkova, Natalia Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITYOF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Heterogeneity and uniformity in the evidential domain A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics by Natalia Korotkova 2016 © Copyright by Natalia Korotkova 2016 ABSTRACTOFTHE DISSERTATION Heterogeneity and uniformity in the evidential domain by Natalia Korotkova Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Dominique L. Sportiche, Co-chair Professor Yael Sharvit, Co-chair The dissertation is devoted to the formal mechanisms that govern the use of evidentials, expressions of natural language that denote the source of information for the proposition conveyed by a sentence. Specifically, I am concerned with putative cases of semantic variation in evidentiality and with its previously unnoticed semantic uniformity. An ongoing debate in this area concerns the relation between evidentiality and epistemic modality. According to one line of research, all evidentials are garden variety epistemic modals. According to another, evidentials across languages fall into two semantic classes: (i) modal evidentials; and (ii) illocutionary evidentials, which deal with the structure of speech acts. The dissertation provides a long-overdue discussion of analytical options proposed for evidentials, and shows that the debate is lacking formally-explicit tools that would differenti- ate between the two classes. Current theories, even though motivated by superficially different data, make in fact very similar predictions. -

Modeling the Lifespan of Discourse Entities with Application to Coreference Resolution

Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 52 (2015) 445-475 Submitted 09/14; published 03/15 Modeling the Lifespan of Discourse Entities with Application to Coreference Resolution Marie-Catherine de Marneffe [email protected] Linguistics Department The Ohio State University Columbus, OH 43210 USA Marta Recasens [email protected] Google Inc. Mountain View, CA 94043 USA Christopher Potts [email protected] Linguistics Department Stanford University Stanford, CA 94035 USA Abstract A discourse typically involves numerous entities, but few are mentioned more than once. Dis- tinguishing those that die out after just one mention (singleton) from those that lead longer lives (coreferent) would dramatically simplify the hypothesis space for coreference resolution models, leading to increased performance. To realize these gains, we build a classifier for predicting the singleton/coreferent distinction. The model’s feature representations synthesize linguistic insights about the factors affecting discourse entity lifespans (especially negation, modality, and attitude predication) with existing results about the benefits of “surface” (part-of-speech and n-gram-based) features for coreference resolution. The model is effective in its own right, and the feature represen- tations help to identify the anchor phrases in bridging anaphora as well. Furthermore, incorporating the model into two very different state-of-the-art coreference resolution systems, one rule-based and the other learning-based, yields significant performance improvements. 1. Introduction Karttunen imagined a text interpreting system designed to keep track of “all the individuals, that is, events, objects, etc., mentioned in the text and, for each individual, record whatever is said about it” (Karttunen, 1976, p. 364). -

From Being to Givenness and Back: Some Remarks on the Meaning Of

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Philosophy Faculty Research and Publications Philosophy, Department of 9-1-2007 From Being to Givenness and Back: Some Remarks on the Meaning of Transcendental Idealism in Kant and Husserl Sebastian Luft Marquette University, [email protected] Accepted version. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, Vol. 15, No. 3 (September 2007): 367-394. DOI. © 2007 Taylor & Francis. Used with permission. From Being to Givenness and Back: Some Remarks on the Meaning of Transcendental Idealism in Kant and Husserl By Sebastian Luft This paper takes a fresh look at a classical theme in philosophical scholarship, the meaning of transcendental idealism, by contrasting Kant’s and Husserl’s versions of it. I present Kant’s transcendental idealism as a theory distinguishing between the world as in-itself and as given to the experiencing human being. This reconstruction provides the backdrop for Husserl’s transcendental phenomenology as a brand of transcendental idealism expanding on Kant: through the phenomenological reduction Husserl universalizes Kant’s transcendental philosophy to an eidetic science of subjectivity. He thereby furnishes a new sense of transcendental philosophy, rephrases the quid iurisquestion, and provides a new conception of the thing-in- itself. What needs to be clarified is not exclusively the possibility of a priori cognition but, to start at a much lower level, the validity of objects that give themselves in experience. The thing-in- itself is not an unknowable object, but the idea of the object in all possible appearances experienced at once. In spite of these changes Husserl remains committed to the basic sense of Kant’s Copernican Turn. -

Discourse-Givenness of Noun Phrases Theoretical and Computational Models

Discourse-Givenness of Noun Phrases Theoretical and Computational Models Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) der Humanwissenschaftlichen Fakult¨at der Universit¨atPotsdam vorgelegt von Julia Ritz Stuttgart, Mai 2013 Published online at the Institutional Repository of the University of Potsdam: URL http://opus.kobv.de/ubp/volltexte/2014/7081/ URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus-70818 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus-70818 Erkl¨arung(Declaration of Authenticity of Work) Hiermit erkl¨areich, dass ich die beigef¨ugteDissertation selbstst¨andigund ohne die un- zul¨assigeHilfe Dritter verfasst habe. Ich habe keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel genutzt. Alle w¨ortlich oder inhaltlich ¨ubernommenen Stellen habe ich als solche gekennzeichnet. Ich versichere außerdem, dass ich die Dissertation in der gegenw¨artigenoder einer an- deren Fassung nur in diesem und keinem anderen Promotionsverfahren eingereicht habe, und dass diesem Promotionsverfahren keine endg¨ultiggescheiterten Promotionsverfahren vorausgegangen sind. Im Falle des erfolgreichen Abschlusses des Promotionsverfahrens erlaube ich der Fakult¨at, die angef¨ugtenZusammenfassungen zu ver¨offentlichen. Ort, Datum Unterschrift iii iv iv Contents Preface xiii 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Discourse-Givenness and Related Concepts . .3 1.2 Goal . .4 1.3 Motivation . .6 1.4 The Field of Discourse-Givenness Classification . 10 1.5 Structure of this Document . 11 2 Concepts and Definitions 13 2.1 Basic Concepts and Representation . 13 2.1.1 Basic Concepts in Discourse . 14 2.1.2 Formal Representation . 15 2.2 Reference . 18 2.2.1 Identifying Basic Units . 20 2.2.2 Non-Referring Use of Expressions . -

The Role of Focus Particles in Wh-Interrogatives: Evidence from a Southern Ryukyuan Language

TheRoleofFocusParticlesinWh-Interrogatives: EvidencefromaSouthernRyukyuanLanguage ChristopherDavis UniversityoftheRyukyus 1. Introduction This paper examines the role of the focus particle du in the formation of wh-interrogatives in the Miyara variety of Yaeyaman, a Ryukyuan language spoken on and around Ishigaki island in Okinawa prefecture, Japan.1 In Miyaran wh-interrogatives, wh-phrases are often marked with du. In assertive reponses to wh-questions, the constituent corresponding to the wh-phrase also shows a strong tendency to be marked by du. This is illustrated by the examples in (1).2 (1) Subject wh-question and answer: a. taa=du suba=ba fai. who=DU soba=PRT ate “Who ate soba?” b. kurisu=n=du suba=ba fai. Chris=NOM=DU soba=PRT ate “Chris ate soba.” (2) Object wh-question and answer: a. kurisu=ja noo=ba=du fai. Chris=TOP what=PRT=DU ate “What did Chris eat?” b. kurisu=ja suba=ba=du fai. Chris=TOP soba=PRT=DU ate “Chris ate soba.” It seems that leaving du off of a wh-phrase in a core argument position (subject or direct object) leads to ungrammaticality: * The data in this paper comes from fieldwork by the author with native speakers of Miyaran, to whom I express my heartfelt gratitude. I have received a particularly large amount of help from Shigeo Arakaki. This research was supported in part by a Grant in Aid for JSPS fellows and by JSPS Grant in Aid for Research 24242014. Examples are elicited data from my own fieldwork, except where noted. Data from other sources are modified to fit the transcription and glossing conventions adopted in this paper. -

Emre ŞAN Intentionality and Givenness in French Phenomenology

Intentionality and Givenness in French Phenomenology: 2017/29 65 Kaygı Uludağ Üniversitesi Fen-Edebiyat Fakültesi Felsefe Dergisi Uludağ University Faculty of Arts and Sciences Journal of Philosophy Sayı 29 / Issue 29│Güz 2017 / Fall 2017 ISSN: 1303-4251 Research Article | Araştırma Makalesi Received | Makale Geliş: 08.05.2017 Accepted | Makale Kabul: 18.09.2017 DOI: 10.20981/kaygi.342182 Emre ŞAN Yrd. Doç. Dr. | Assist. Prof. Dr. İstanbul 29 Mayıs Üniversitesi, Edebiyat Fakültesi, Felsefe Bölümü, TR Istanbul 29 Mayıs University, Faculty of Literature, Department of Philosophy, TR [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0003-2654-9707 Intentionality and Givenness in French Phenomenology: M. Henry and M. Merleau Ponty Abstract My guiding research hypothesis is as follows: the significant progress made by the phenomenology of immanence (according to which no worldly hetero-givenness would be possible without subjectif self-givenness) and by the phenomenology of transcendence (which states that no subjectif self-givenness would be possible without worldly hetero-givenness) are not distinguished so much by the positing of new problems as by the reformulation of “the question of the ground of intentionality” that fueled the entire phenomenological tradition. It is striking that despite the different solutions they offer, these two approaches have the same critical orientation regarding phenomenology (they characterize intentionality by its failure to ensure its own foundation), and they have the task of testing phenomenology in a confrontation with its various outsides such as “Invisible”, “Totality”, “Affectivity” or “Le visage” which escape the Husserlian concept of experience determined by the consciousness and its correlative noetic-noematic structure. This pathos of thought which is proper to the French phenomenology wants to go further than what remains unquestioned in Husserl (presence determined in the solid figures of intuition and objectness), and in Heidegger (presence determined as phenomenon of being).