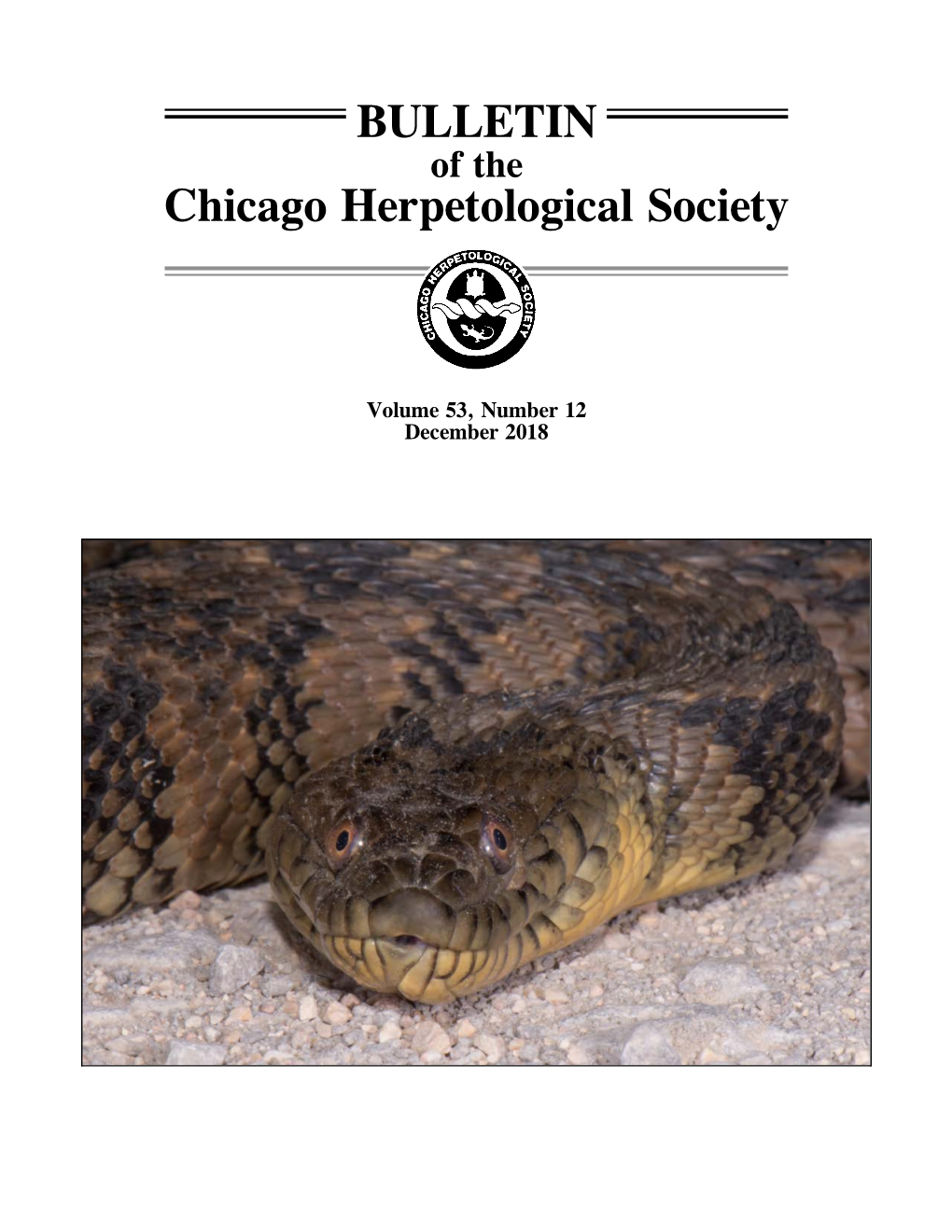

BULLETIN Chicago Herpetological Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Third International Symposium on Mangroves As Fish Habitat Abstracts*

Bull Mar Sci. 96(3):539–560. 2020 abstracts https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2019.0047 Third International Symposium on Mangroves as Fish Habitat Abstracts* COMMUNITY COMPOSITION AND DIVERSITY OF PHYTOPLANKTON IN RELATION TO ENVIRONMENTAL VARIABLES AND SEASONALITY IN A TROPICAL MANGROVE ESTUARY, MALAYSIA by ABU HENA MK, Saifullah ASM, Idris MH, Rajaee AH, Rahman MM.—Phytoplankton are the base of the aquatic food chain from which energy is transferred to higher organisms. The community and abundance of phytoplankton in a tropical mangrove estuary were examined in Sarawak, Malaysia. Monthly-collected data from January 2013 to December 2013 was pooled into seasons to examine the influence of seasonality. The estuary was relatively species-rich and a total of 102 species under 43 genera were recorded, comprising 6 species of Cyanophyceae, 4 species of Chlorophyceae, 63 species of Bacillariophyceae, and 29 species of Dinophyceae. The mean abundance (cells L−1) of phytoplankton was found in the following order: Bacillariophyceae > Dinophyceae > Cyanophyceae > Chlorophyceae. Mean abundance of phytoplankton ranged from 5694 to 88,890 cells L−1 over the study period, with a higher value in the dry season. Species recorded from the estuary were dominated by Pleurosigma normanii, Coscinodiscus sp., Coscinodiscus centralis, Coscinodiscus granii, Dinophysis caudata, Ceratium carriense, Ceratium fusus, and Ceratium lineatum. Abundance of phytoplankton was positively influenced by chlorophyll a (R = 0.69), ammonium (R = 0.64), and silica (R = 0.64). Significant differences (ANOSIM and NMDS) were observed in the species community structure between the intermediate and wet season. The species assemblages were positively correlated with surface water temperature, salinity, pH, ammonium, and nitrate in the intermediate and dry season toward larger species composition in the respective seasons, whereas silica influenced species assemblage in the wet season. -

(Gloydius Blomhoffii) Antivenom in Japan, Korea, and China

Jpn. J. Infect. Dis., 59, 20-24, 2006 Original Article Standardization of Regional Reference for Mamushi (Gloydius blomhoffii) Antivenom in Japan, Korea, and China Tadashi Fukuda*, Masaaki Iwaki, Seung Hwa Hong1, Ho Jung Oh1, Zhu Wei2, Kazunori Morokuma3, Kunio Ohkuma3, Lei Dianliang4, Yoshichika Arakawa and Motohide Takahashi Department of Bacterial Pathogenesis and Infection Control, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo 208-0011; 3First, Production Department, Chemo-Sero-Therapeutic Research Institute, Kumamoto 860-8568, Japan; 1Korea Food and Drug Administration, Soul 122-704, Korea; 2Shanghai Institute of Biological Products, Shanghai 200052; and 4Department of Serum, National Institute for the Control of Pharmaceutical and Biological Products, Beijing 10050, People’s Republic of China (Received June 27, 2005. Accepted November 11, 2005) SUMMARY: The mamushi (Gloydius blomhoffii) snakes that inhabit Japan, Korea, and China produce venoms with similar serological characters to each other. Individual domestic standard mamushi antivenoms have been used for national quality control (potency testing) of mamushi antivenom products in these countries, because of the lack of an international standard material authorized by the World Health Organization. This precludes comparison of the results of product potency testing among countries. We established a regional reference antivenom for these three Asian countries. This collaborative study indicated that the regional reference mamushi antivenom has an anti-lethal titer of 33,000 U/vial and anti-hemorrhagic titer of 36,000 U/vial. This reference can be used routinely for quality control, including national control of mamushi antivenom products. reference antivenom. INTRODUCTION In the present study, the potency of a candidate regional Snakebites are a threat to human life in areas inhabited by reference mamushi antivenom produced by Shanghai Insti- poisonous snakes. -

Ecology, Behavior and Conservation of the Japanese Mamushi Snake, Gloydius Blomhoffii: Variation in Compromised and Uncompromised Populations

ECOLOGY, BEHAVIOR AND CONSERVATION OF THE JAPANESE MAMUSHI SNAKE, GLOYDIUS BLOMHOFFII: VARIATION IN COMPROMISED AND UNCOMPROMISED POPULATIONS By KIYOSHI SASAKI Bachelor of Arts/Science in Zoology Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK 1999 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2006 ECOLOGY, BEHAVIOR AND CONSERVATION OF THE JAPANESE MAMUSHI SNAKE, GLOYDIUS BLOMHOFFII: VARIATION IN COMPROMISED AND UNCOMPROMISED POPULATIONS Dissertation Approved: Stanley F. Fox Dissertation Adviser Anthony A. Echelle Michael W. Palmer Ronald A. Van Den Bussche A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I sincerely thank the following people for their significant contribution in my pursuit of a Ph.D. degree. I could never have completed this work without their help. Dr. David Duvall, my former mentor, helped in various ways until the very end of his career at Oklahoma State University. This study was originally developed as an undergraduate research project under Dr. Duvall. Subsequently, he accepted me as his graduate student and helped me expand the project to this Ph.D. research. He gave me much key advice and conceptual ideas for this study. His encouragement helped me to get through several difficult times in my pursuit of a Ph.D. degree. He also gave me several books as a gift and as an encouragement to complete the degree. Dr. Stanley Fox kindly accepted to serve as my major adviser after Dr. Duvall’s departure from Oklahoma State University and involved himself and contributed substantially to this work, including analysis and editing. -

Reptiles in Arkansas

Terrestrial Reptile Report Carphophis amoenus Co mmon Wor msnake Class: Reptilia Order: Serpentes Family: Colubridae Priority Score: 19 out of 100 Population Trend: Unknown Global Rank: G5 — Secure State Rank: S2 — Imperiled in Arkansas Distribution Occurrence Records Ecoregions where the species occurs: Ozark Highlands Boston Mountains Arkansas Valley Ouachita Mountains South Central Plains Mississippi Alluvial Plain Mississippi Valley Loess Plain Carphophis amoenus Common Wormsnake 1079 Terrestrial Reptile Report Habitat Map Habitats Weight Crowley's Ridge Loess Slope Forest Obligate Lower Mississippi Flatwoods Woodland and Forest Suitable Problems Faced KNOWN PROBLEM: Habitat loss due to conversion Threat: Habitat destruction or to agriculture. conversion Source: Agricultural practices KNOWN PROBLEM: Habitat loss due to forestry Threat: Habitat destruction or practices. conversion Source: Forestry activities Data Gaps/Research Needs Genetic analyses comparing Arkansas populations with populations east of the Mississippi River and the Western worm snake. Conservation Actions Importance Category More data are needed to determine conservation actions. Monitoring Strategies More information is needed to develop a monitoring strategy. Carphophis amoenus Common Wormsnake 1080 Terrestrial Reptile Report Comments Trauth and others (2004) summarized the literature and biology of this snake. In April 2005, two new geographic distribution records were collected in Loess Slope Forest habitat within St. Francis National Forest, south of the Mariana -

2008 Board of Governors Report

American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Board of Governors Meeting Le Centre Sheraton Montréal Hotel Montréal, Quebec, Canada 23 July 2008 Maureen A. Donnelly Secretary Florida International University Biological Sciences 11200 SW 8th St. - OE 167 Miami, FL 33199 [email protected] 305.348.1235 31 May 2008 The ASIH Board of Governor's is scheduled to meet on Wednesday, 23 July 2008 from 1700- 1900 h in Salon A&B in the Le Centre Sheraton, Montréal Hotel. President Mushinsky plans to move blanket acceptance of all reports included in this book. Items that a governor wishes to discuss will be exempted from the motion for blanket acceptance and will be acted upon individually. We will cover the proposed consititutional changes following discussion of reports. Please remember to bring this booklet with you to the meeting. I will bring a few extra copies to Montreal. Please contact me directly (email is best - [email protected]) with any questions you may have. Please notify me if you will not be able to attend the meeting so I can share your regrets with the Governors. I will leave for Montréal on 20 July 2008 so try to contact me before that date if possible. I will arrive late on the afternoon of 22 July 2008. The Annual Business Meeting will be held on Sunday 27 July 2005 from 1800-2000 h in Salon A&C. Please plan to attend the BOG meeting and Annual Business Meeting. I look forward to seeing you in Montréal. Sincerely, Maureen A. Donnelly ASIH Secretary 1 ASIH BOARD OF GOVERNORS 2008 Past Presidents Executive Elected Officers Committee (not on EXEC) Atz, J.W. -

The Corrected Lengths of Two Well-Known Giant Pythons and the Establishment of a New Maximum Length Record for Burmese Pythons, Python Bivittatus David G

Bull. Chicago Herp. Soc. 47(1):1-6, 2012 The Corrected Lengths of Two Well-known Giant Pythons and the Establishment of a New Maximum Length Record for Burmese Pythons, Python bivittatus David G. Barker 1, Stephen L. Barten, DVM 2, Jonas P. Ehrsam 3 and Louis Daddono There is strong popular interest in the sizes of giant pythons In the course of our investigations, we have even come to that dates far back into history and continues to the present day. question the actual length of what is widely accepted as the This was particularly well illustrated by the media hysteria that largest snake ever maintained in captivity, that being “Colos- followed the USGS news release on 20 February 2008 that was sus,” a reticulated python, Broghammerus reticulatus, that titled “USGS Maps Show Potential Non-Native Python Habitat resided in the Pittsburgh Zoo from 1949 until 1963. The history Along Three U.S. Coasts.” The report that followed described of Colossus is perhaps the best example of the discrepancy the Burmese python as “huge” with a maximum size of 7–8 m between purported size and actual measured size. (23 ft–26 ft 3 in) (Rodda et al., 2008/2009; Reed and Rodda, 2009). The countless newspaper articles, news reports and Colossus documentaries that followed typically stressed the “massive” The reticulated python known as Colossus arrived at the size of Burmese pythons and of pythons in general. Highland Park Zoo [now known as the Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG We have seen a lot of Burmese pythons in captivity over the Aquarium] in August 1949 and remained there on exhibit until past 40 years, and none approached those lengths. -

Climate Change and Evolution of the New World Pitviper Genus

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2009) 36, 1164–1180 ORIGINAL Climate change and evolution of the New ARTICLE World pitviper genus Agkistrodon (Viperidae) Michael E. Douglas1*, Marlis R. Douglas1, Gordon W. Schuett2 and Louis W. Porras3 1Illinois Natural History Survey, Institute for ABSTRACT Natural Resource Sustainability, University of Aim We derived phylogenies, phylogeographies, and population demographies Illinois, Champaign, IL, 2Department of Biology and Center for Behavioral for two North American pitvipers, Agkistrodon contortrix (Linnaeus, 1766) and Neuroscience, Georgia State University, A. piscivorus (Lace´pe`de, 1789) (Viperidae: Crotalinae), as a mechanism to Atlanta, GA and 37705 Wyatt Earp Avenue, evaluate the impact of rapid climatic change on these taxa. Eagle Mountain, UT, USA Location Midwestern and eastern North America. Methods We reconstructed maximum parsimony (MP) and maximum likelihood (ML) relationships based on 846 base pairs of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) ATPase 8 and ATPase 6 genes sequenced over 178 individuals. We quantified range expansions, demographic histories, divergence dates and potential size differences among clades since their last period of rapid expansion. We used the Shimodaira–Hasegawa (SH) test to compare our ML tree against three biogeographical hypotheses. Results A significant SH test supported diversification of A. contortrix from northeastern Mexico into midwestern–eastern North America, where its trajectory was sundered by two vicariant events. The first (c. 5.1 Ma) segregated clades at 3.1% sequence divergence (SD) along a continental east–west moisture gradient. The second (c. 1.4 Ma) segregated clades at 2.4% SD along the Mississippi River, coincident with the formation of the modern Ohio River as a major meltwater tributary. -

Project Name

SYRAH RESOURCES GRAPHITE PROJECT, CABO DELGADO, MOZAMBIQUE TERRESTRIAL FAUNAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Prepared by: Prepared for: Syrah Resources Limited Coastal and Environmental Services Mozambique, Limitada 356 Collins Street Rua da Frente de Libertação de Melbourne Moçambique, Nº 324 3000 Maputo- Moçambique Australia Tel: (+258) 21 243500 • Fax: (+258) 21 243550 Website: www.cesnet.co.za December 2013 Syrah Final Faunal Impact Assessment – December 2013 AUTHOR Bill Branch, Terrestrial Vertebrate Faunal Consultant Bill Branch obtained B.Sc. and Ph.D. degrees at Southampton University, UK. He was employed for 31 years as the herpetologist at the Port Elizabeth Museum, and now retired holds the honorary post of Curator Emeritus. He has published over 260 scientific articles, as well as numerous popular articles and books. The latter include the Red Data Book for endangered South African reptiles and amphibians (1988), and co-editing its most recent upgrade – the Atlas and Red Data Book of the Reptiles of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland (2013). He has also published guides to the reptiles of both Southern and Eastern Africa. He has chaired the IUCN SSC African Reptile Group. He has served as an Honorary Research Professor at the University of Witwatersrand (Johannesburg), and has recently been appointed as a Research Associate at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, Port Elizabeth. His research concentrates on the taxonomy, biogeography and conservation of African reptiles, and he has described over 30 new species and many other higher taxa. He has extensive field work experience, having worked in over 16 African countries, including Gabon, Ivory Coast, DRC, Zambia, Mozambique, Malawi, Madagascar, Namibia, Angola and Tanzania. -

AG-472-02 Snakes

Snakes Contents Intro ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................1 What are Snakes? ...............................................................1 Biology of Snakes ...............................................................1 Why are Snakes Important? ............................................1 People and Snakes ............................................................3 Where are Snakes? ............................................................1 Managing Snakes ...............................................................3 Family Colubridae ...............................................................................................................................................................................................5 Eastern Worm Snake—Harmless .................................5 Red-Bellied Water Snake—Harmless ....................... 11 Scarlet Snake—Harmless ................................................5 Banded Water Snake—Harmless ............................... 11 Black Racer—Harmless ....................................................5 Northern Water Snake—Harmless ............................12 Ring-Necked Snake—Harmless ....................................6 Brown Water Snake—Harmless .................................12 Mud Snake—Harmless ....................................................6 Rough Green Snake—Harmless .................................12 -

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 68 (2013) 425–431

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 68 (2013) 425–431 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Testing monophyly without well-supported gene trees: Evidence from multi-locus nuclear data conflicts with existing taxonomy in the snake tribe Thamnophiini ⇑ John David McVay a, , Bryan Carstens b a Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, 202 Life Sciences Building, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, United States b Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology, The Ohio State University, 318 W. 12th Avenue, Columbus, OH 43210, United States article info abstract Article history: Ideally, existing taxonomy would be consistent with phylogenetic estimates derived from rigorously ana- Received 6 October 2012 lyzed data using appropriate methods. We present a multi-locus molecular analysis of the relationships Revised 19 April 2013 among nine genera in the North American snake tribe Thamnophiini in order to test the monophyly of the Accepted 22 April 2013 crayfish snakes (genus Regina) and the earth snakes (genus Virginia). Sequence data from seven genes Available online 9 May 2013 were analyzed to assess relationships among representatives of the nine genera by performing multi- locus phylogeny and species tree estimations, and we performed constraint-based tests of monophyly Keywords: of classic taxonomic designations on a gene-by-gene basis. Estimates of concatenated phylogenies dem- Monophyly onstrate that neither genera are monophyletic, and this inference is supported by a species tree estimate, Regina Virginia though the latter is less robust. These taxonomic findings were supported using gene tree constraint tests Liodytes and Bayes Factors, where we rejected the monophyly of both the crayfish snakes (genus Regina) and the Haldea earth snakes (genus Virginia); this method represents a potentially useful tool for taxonomists and phy- Stepping stone sampling logeneticists when available data is less than ideal. -

Patterns of Species Richness, Endemism and Environmental Gradients of African Reptiles

Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.) (2016) ORIGINAL Patterns of species richness, endemism ARTICLE and environmental gradients of African reptiles Amir Lewin1*, Anat Feldman1, Aaron M. Bauer2, Jonathan Belmaker1, Donald G. Broadley3†, Laurent Chirio4, Yuval Itescu1, Matthew LeBreton5, Erez Maza1, Danny Meirte6, Zoltan T. Nagy7, Maria Novosolov1, Uri Roll8, 1 9 1 1 Oliver Tallowin , Jean-Francßois Trape , Enav Vidan and Shai Meiri 1Department of Zoology, Tel Aviv University, ABSTRACT 6997801 Tel Aviv, Israel, 2Department of Aim To map and assess the richness patterns of reptiles (and included groups: Biology, Villanova University, Villanova PA 3 amphisbaenians, crocodiles, lizards, snakes and turtles) in Africa, quantify the 19085, USA, Natural History Museum of Zimbabwe, PO Box 240, Bulawayo, overlap in species richness of reptiles (and included groups) with the other ter- Zimbabwe, 4Museum National d’Histoire restrial vertebrate classes, investigate the environmental correlates underlying Naturelle, Department Systematique et these patterns, and evaluate the role of range size on richness patterns. Evolution (Reptiles), ISYEB (Institut Location Africa. Systematique, Evolution, Biodiversite, UMR 7205 CNRS/EPHE/MNHN), Paris, France, Methods We assembled a data set of distributions of all African reptile spe- 5Mosaic, (Environment, Health, Data, cies. We tested the spatial congruence of reptile richness with that of amphib- Technology), BP 35322 Yaounde, Cameroon, ians, birds and mammals. We further tested the relative importance of 6Department of African Biology, Royal temperature, precipitation, elevation range and net primary productivity for Museum for Central Africa, 3080 Tervuren, species richness over two spatial scales (ecoregions and 1° grids). We arranged Belgium, 7Royal Belgian Institute of Natural reptile and vertebrate groups into range-size quartiles in order to evaluate the Sciences, OD Taxonomy and Phylogeny, role of range size in producing richness patterns. -

Mammals, Birds, Herps

Zambezi Basin Wetlands Volume II : Chapters 3 - 6 - Contents i Back to links page CONTENTS VOLUME II Technical Reviews Page CHAPTER 3 : REDUNCINE ANTELOPE ........................ 145 3.1 Introduction ................................................................. 145 3.2 Phylogenetic origins and palaeontological background 146 3.3 Social organisation and behaviour .............................. 150 3.4 Population status and historical declines ................... 151 3.5 Taxonomy and status of Reduncine populations ......... 159 3.6 What are the species of Reduncine antelopes? ............ 168 3.7 Evolution of Reduncine antelopes in the Zambezi Basin ....................................................................... 177 3.8 Conservation ................................................................ 190 3.9 Conclusions and recommendations ............................. 192 3.10 References .................................................................... 194 TABLE 3.4 : Checklist of wetland antelopes occurring in the principal Zambezi Basin wetlands .................. 181 CHAPTER 4 : SMALL MAMMALS ................................. 201 4.1 Introduction ..................................................... .......... 201 4.2 Barotseland small mammals survey ........................... 201 4.3 Zambezi Delta small mammal survey ....................... 204 4.4 References .................................................................. 210 CHAPTER 5 : WETLAND BIRDS ...................................... 213 5.1 Introduction ..................................................................