Water Scarcity, Conflict, and Migration: a Comparative Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palestinian Territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY and WEST ASIA

Palestinian territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY AND WEST ASIA Basic socio-economic indicators Income group - LOWER MIDDLE INCOME Local currency - Israeli new shekel (ILS) Population and geography Economic data AREA: 6 020 km2 GDP: 19.4 billion (current PPP international dollars) i.e. 4 509 dollars per inhabitant (2014) POPULATION: million inhabitants (2014), an increase 4.295 REAL GDP GROWTH: -1.5% (2014 vs 2013) of 3% per year (2010-2014) UNEMPLOYMENT RATE: 26.9% (2014) 2 DENSITY: 713 inhabitants/km FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT, NET INFLOWS (FDI): 127 (BoP, current USD millions, 2014) URBAN POPULATION: 75.3% of national population GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION (GFCF): 18.6% of GDP (2014) CAPITAL CITY: Ramallah (2% of national population) HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: 0.677 (medium), rank 113 Sources: World Bank; UNDP-HDR, ILO Territorial organisation and subnational government RESPONSIBILITIES MUNICIPAL LEVEL INTERMEDIATE LEVEL REGIONAL OR STATE LEVEL TOTAL NUMBER OF SNGs 483 - - 483 Local governments - Municipalities (baladiyeh) Average municipal size: 8 892 inhabitantS Main features of territorial organisation. The Palestinian Authority was born from the Oslo Agreements. Palestine is divided into two main geographical units: the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. It is still an ongoing State construction. The official government of Cisjordania is governed by a President, while the Gaza area is governed by the Hamas. Up to now, most governmental functions are ensured by the State of Israel. In 1994, and upon the establishment of the Palestinian Ministry of Local Government (MoLG), 483 local government units were created, encompassing 103 municipalities and village councils and small clusters. Besides, 16 governorates are also established as deconcentrated level of government. -

Measuring Public Opinion Regarding Peaceful Solution of Palestine Issue

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: F Political Science Volume 14 Issue 4 Version 1.0 Year 2014 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Measuring Public Opinion Regarding Peaceful Solution of Palestine Issue: An Experimental Study of University Students in Pakistan, Iran and United Arab Emirates By Muhammad Asim Government Postgraduate College Asghar Mall, Pakistan Abstract- This study aimed to measure public opinion in the Pakistan, Iran and United Arab Emirates regarding peaceful solution of Palestine issue Data (N=276) was collected from two universities, one postgraduate college and one degree college in Pakistan, two universities in Iran and two universities in United Arab Emirates. Although, Pakistan and Iran have theocratic environment and we got anti-Israel replies but there were 77 Pakistani and 41 Emirati students who presented their rational views about peaceful solution of this conflict. There is a brief debate on One-State Solution, Two-States Solution, Three-States Solution and the status of Jerusalem. The plan of forming union among the territories of Israel and Palestine, single currency and Rail-Road plan for secular transportation from one region to another is also discussed in this study. During comparing such public opinion with other previous international proposals for resolving this issue, recommendations from the author are presented in the last. Keywords: uae, i-p union, religiosity, eu, state of judea. -

Introduction to the Geography of Southwest Asia Name ______Date ______Pd _____

Introduction to the geography of Southwest Asia Name ____________________________________ Date _______________________ Pd _____ Tigris River *begins in Turkey and travel through Syria and Iraq *empties into the Persian GulfThey are the *largest rivers in Southwest Asia *essential source of water Euphrates River *Because of the importance of their waters, they are source of conflict *nations argue over control of this important natural resource Jordan River *forms the border between the nation of Jordan and the Palestinian Territory known as the West Bank. *Control of the Jordan River’s water is a source of dispute between the Palestinians and the Israelis. Suez Canal *connects the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea *it is an important trade route Strait of Hormuz *narrow shallow body of water that connects the Persian Gulf to the Arabian Sea *important trade route connecting the rich oil fields of the gulf to the Arabian Sea and beyond. Arabian Sea *south of Saudi Arabia. *For centuries, the Arabian Sea has been a key link in the Indian Ocean trade and remains a major trade route. Red Sea *sea separating Africa from South West Asia *connects the Arabian Sea to the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal. Gaza Strip *narrow strip of land between Israel, Egypt, and the Mediterranean Sea *Gaza Strip is home to millions of Palestinian Refugees who fled there during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War *frequent conflicts between its Arab inhabitants and Israeli Jews. Introduction to the geography of Southwest Asia Name ____________________________________ Date -

ICC-01/18 Date: 16 March 2020 PRE

ICC-01/18-111 17-03-2020 1/10 NM PT Original: English No.: ICC-01/18 Date: 16 March 2020 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER I Before: Judge Péter Kovács, Presiding Judge Judge Marc Perrin de Brichambaut Judge Reine Adélaïde Sophie Alapini-Gansou SITUATION IN THE STATE OF PALESTINE Public Amicus Curiae Submission of Observations Pursuant to Rule 103 Source: Intellectum Scientific Society (hereinafter Intellectum) No. ICC-01/18 1/10 ICC-01/18-111 17-03-2020 2/10 NM PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Fatou Bensouda, Prosecutor James Stewart, Deputy Prosecutor Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence Paolina Massidda States’ Representatives Amici Curiae The competent authorities of the ▪ Professor John Quigley State of Palestine ▪ Guernica 37 International Justice The competent authorities of the Chambers State of Israel ▪ The European Centre for Law and Justice ▪ Professor Hatem Bazian ▪ The Touro Institute on Human Rights and the Holocaust ▪ The Czech Republic ▪ The Israel Bar Association ▪ Professor Richard Falk ▪ The Organization of Islamic Cooperation ▪ The Lawfare Project, the Institute for NGO Research, Palestinian Media Watch, & the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs ▪ MyAQSA ▪ Professor Eyal Benvenisti ▪ The Federal Republic of Germany ▪ Australia No. ICC-01/18 2/10 ICC-01/18-111 17-03-2020 3/10 NM PT ▪ UK Lawyers for Israel, B’nai B’rith UK, the International Legal Forum, the Jerusalem Initiative and the Simon Wiesenthal Centre ▪ The Palestinian Bar Association ▪ Prof. -

A Pre-Feasibility Study on Water Conveyance Routes to the Dead

A PRE-FEASIBILITY STUDY ON WATER CONVEYANCE ROUTES TO THE DEAD SEA Published by Arava Institute for Environmental Studies, Kibbutz Ketura, D.N Hevel Eilot 88840, ISRAEL. Copyright by Willner Bros. Ltd. 2013. All rights reserved. Funded by: Willner Bros Ltd. Publisher: Arava Institute for Environmental Studies Research Team: Samuel E. Willner, Dr. Clive Lipchin, Shira Kronich, Tal Amiel, Nathan Hartshorne and Shae Selix www.arava.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 HISTORICAL REVIEW 5 2.1 THE EVOLUTION OF THE MED-DEAD SEA CONVEYANCE PROJECT ................................................................... 7 2.2 THE HISTORY OF THE CONVEYANCE SINCE ISRAELI INDEPENDENCE .................................................................. 9 2.3 UNITED NATIONS INTERVENTION ......................................................................................................... 12 2.4 MULTILATERAL COOPERATION ............................................................................................................ 12 3 MED-DEAD PROJECT BENEFITS 14 3.1 WATER MANAGEMENT IN ISRAEL, JORDAN AND THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY ............................................... 14 3.2 POWER GENERATION IN ISRAEL ........................................................................................................... 18 3.3 ENERGY SECTOR IN THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 20 3.4 POWER GENERATION IN JORDAN ........................................................................................................ -

Egypt and Israel: Tunnel Neutralization Efforts in Gaza

WL KNO EDGE NCE ISM SA ER IS E A TE N K N O K C E N N T N I S E S J E N A 3 V H A A N H Z И O E P W O I T E D N E Z I A M I C O N O C C I O T N S H O E L C A I N M Z E N O T Egypt and Israel: Tunnel Neutralization Efforts in Gaza LUCAS WINTER Open Source, Foreign Perspective, Underconsidered/Understudied Topics The Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is an open source research organization of the U.S. Army. It was founded in 1986 as an innovative program that brought together military specialists and civilian academics to focus on military and security topics derived from unclassified, foreign media. Today FMSO maintains this research tradition of special insight and highly collaborative work by conducting unclassified research on foreign perspectives of defense and security issues that are understudied or unconsidered. Author Background Mr. Winter is a Middle East analyst for the Foreign Military Studies Office. He holds a master’s degree in international relations from Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and was an Arabic Language Flagship Fellow in Damascus, Syria, in 2006–2007. Previous Publication This paper was originally published in the September-December 2017 issue of Engineer: the Professional Bulletin for Army Engineers. It is being posted on the Foreign Military Studies Office website with permission from the publisher. FMSO has provided some editing, format, and graphics to this paper to conform to organizational standards. -

THE PLO and the PALESTINIAN ARMED STRUGGLE by Professor Yezid Sayigh, Department of War Studies, King's College London

THE PLO AND THE PALESTINIAN ARMED STRUGGLE by Professor Yezid Sayigh, Department of War Studies, King's College London The emergence of a durable Palestinian nationalism was one of the more remarkable developments in the history of the modern Middle East in the second half of the 20th century. This was largely due to a generation of young activists who proved particularly adept at capturing the public imagination, and at seizing opportunities to develop autonomous political institutions and to promote their cause regionally and internationally. Their principal vehicle was the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), while armed struggle, both as practice and as doctrine, was their primary means of mobilizing their constituency and asserting a distinct national identity. By the end of the 1970s a majority of countries – starting with Arab countries, then extending through the Third World and the Soviet bloc and other socialist countries, and ending with a growing number of West European countries – had recognized the PLO as the legitimate representative of the Palestinian people. The United Nations General Assembly meanwhile confirmed the right of the stateless Palestinians to national self- determination, a position adopted subsequently by the European Union and eventually echoed, in the form of support for Palestinian statehood, by the United States and Israel from 2001 onwards. None of this was a foregone conclusion, however. Britain had promised to establish a Jewish ‘national home’ in Palestine when it seized the country from the Ottoman Empire in 1917, without making a similar commitment to the indigenous Palestinian Arab inhabitants. In 1929 it offered them the opportunity to establish a self-governing agency and to participate in an elected assembly, but their community leaders refused the offer because it was conditional on accepting continued British rule and the establishment of the Jewish ‘national home’ in what they considered their own homeland. -

Gaza Marine: Natural Gas Extraction in Tumultuous Times?

POLICY PAPER Number 36 February 2015 Gaza Marine: Natural Gas Extraction in Tumultuous Times? TIM BOERSMA NATAN SACHS Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its abso- lute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment, and the analysis and recommenda- tions of the Institution’s scholars are not determined by any donation. Acknowledgements This report, and the larger project of which it is a Chair, Tzemach Committee; and Harry-Zachary part, benefited greatly from the insight and assis- Tzimitras, Director, PRIO Cyprus Centre. tance of a large number of people. We are also very grateful to Ariel Ezrahi, for his For generosity with their time and insights we are comments on earlier drafts of this paper, to Ibra- grateful to: Yossi Abu, CEO Delek Drilling; Eng. heem Egbaria, Ilan Suliman and Firash Qawasmi, Fuad Amleh, Chief Executive Officer, Palestine who helped facilitate our visit to the (East) Jeru- Electricity Transmission, Ltd.; Constantine Blyuz, salem District Electricity Company and to Ohad Deputy Director for Economic & Strategic Issues, Reifen who helped facilitate interviews in Israel. Israeli Ministry of National Infrastructures, Ener- gy and Water Resources; Yael Cohen Paran, CEO, We would also like to thank our Brookings col- Israel Energy Forum; Ariel Ezrahi, Infrastructure leagues: Martin Indyk and Ted Piccone for sup- (Energy) Adviser, Office of the Quartet Represen- porting our work through the Foreign Policy Pro- tative, Mr. Tony Blair; Michalis Firillas, Deputy gram’s Director’s Strategic Initiative Fund; Charles Head of Mission, Consul, Embassy of the Republic Ebinger, for his sage feedback on drafts and, along of Cyprus in Israel; Nurit Gal, Director, Regulation with Tamara Wittes, for guiding us and provid- and Electricity Division, Public Utilities Authori- ing wonderful places within Brookings in which ty of Israel; Dr. -

Israel's Unilateral Withdrawals from Lebanon and the Gaza Strip

Israel’s Unilateral Withdrawals from Lebanon and the Gaza Strip: A Comparative Overview Reuven Erlich Introduction In the last decade, Israel unilaterally withdrew from two areas: the security zone in southern Lebanon and the Gaza Strip. Israel had previously withdrawn unilaterally from occupied territories without political agreements, but these two withdrawals were more significant and traumatic, both socially and politically, than any prior withdrawal. The time that has passed since these unilateral withdrawals affords us some historical perspective and allows us to compare them in terms of their outcomes and the processes they generated, both positive and negative. This perspective allows us to study the larger picture and trace influences that in the heat of the dramatic events were difficult to discern and assess. When looking at Lebanon and Israel’s policies there, my approach is not purely academic or that of an historian who wrote a doctoral thesis on Israeli-Lebanese relations. I participated in some of the events in Lebanon, not as a decision maker but as a professional, whether in the course of my service in Israeli Military Intelligence, both in Tel Aviv and in the Northern Command, or in my position with the Ministry of Defense, as deputy to Uri Lubrani, Coordinator of Government Activities in Lebanon. My perspective today on Lebanon and the Gaza Col. (ret.) Dr. Reuven Erlich is Head of the Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center at the Israel Intelligence Heritage and Commemoration Center (IICC). This essay is based on a lecture delivered at the conference “The Withdrawal from Lebanon: Ten Years Later,” which took place at the Institute for National Security Studies on June 28, 2010. -

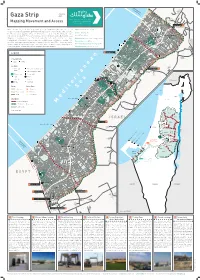

Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary

Zikim Karmiya No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles Yad Mordekhai January Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary Ar-Rasheed Wastewater Treatment Lagoons Sources: OCHA, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics of Statistics Bureau Central OCHA, Palestinian Sources: Erez Crossing 1 Al-Qarya Beit Hanoun Al-Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) Erez What is known today as the Gaza Strip, originally a region in Mandatory Palestine, was created Width 5.7-12.5 km / 3.5 – 7.7 mi through the armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt in 1949. From that time until 1967, North Gaza Length ~40 km / 24.8 mi Al- Karama As-Sekka the Strip was under Egyptian control, cut off from Israel as well as the West Bank, which was Izbat Beit Hanoun al-Jaker Road Area 365 km2 / 141 m2 Beit Hanoun under Jordanian rule. In 1967, the connection was renewed when both the West Bank and the Gaza Madinat Beit Lahia Al-'Awda Strip were occupied by Israel. The 1993 Oslo Accords define Gaza and the West Bank as a single Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Population 1,943,398 • 48% Under age 17 July 2019 Industrial Zone Ash-Shati Housing Project Jabalia Sderot territorial unit within which freedom of movement would be permitted. However, starting in the camp al-Wazeer Unemployment rate 47% 2019 Q2 Jabalia Camp Khalil early 90s, Israel began a gradual process of closing off the Strip; since 2007, it has enforced a full Ash-Sheikh closure, forbidding exit and entry except in rare cases. Israel continues to control many aspects of Percentage of population receiving aid 80% An-Naser Radwan Salah Ad-Deen 2 life in Gaza, most of its land crossings, its territorial waters and airspace. -

Mapping Peace Between Syria and Israel

UNiteD StateS iNStitUte of peaCe www.usip.org SpeCial REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Frederic C. Hof Commissioned in mid-2008 by the United States Institute of Peace’s Center for Mediation and Conflict Resolution, this report builds upon two previous groundbreaking works by the author that deal with the obstacles to Syrian- Israeli peace and propose potential ways around them: a 1999 Middle East Insight monograph that defined the Mapping peace between phrase “line of June 4, 1967” in its Israeli-Syrian context, and a 2002 Israel-Syria “Treaty of Peace” drafted for the International Crisis Group. Both works are published Syria and israel online at www.usip.org as companion pieces to this report and expand upon a concept first broached by the author in his 1999 monograph: a Jordan Valley–Golan Heights Environmental Preserve under Syrian sovereignty that Summary would protect key water resources and facilitate Syrian- • Syrian-Israeli “proximity” peace talks orchestrated by Turkey in 2008 revived a Israeli people-to-people contacts. long-dormant track of the Arab-Israeli peace process. Although the talks were sus- Frederic C. Hof is the CEO of AALC, Ltd., an Arlington, pended because of Israeli military operations in the Gaza Strip, Israeli-Syrian peace Virginia, international business consulting firm. He directed might well facilitate a Palestinian state at peace with Israel. the field operations of the Sharm El-Sheikh (Mitchell) Fact- Finding Committee in 2001. • Syria’s “bottom line” for peace with Israel is the return of all the land seized from it by Israel in June 1967. -

Israel Has Been Home to a Renaissance of Jewish Culture

INTRODUCTION Israel celebrates its 70th birthday this year, 2018, on 19 April. After 2,000 years of exile and persecution, the Jewish people have made up for lost time now that they finally have a state of their own again. Israel has flourished in its first 70 years of statehood and achieved more than many far older countries. Here are 70 of Israel’s achievements we are highlighting – from the sublime and world changing to the small but important: ISRAEL HAS ACHIEVED ITS CORE MISSION OF PROVIDING A STATE FOR THE JEWS WHERE THEY CAN BE FREE FROM PERSECUTION Israel, the only Jewish state, is open to all Jews. It serves as a lifeboat state for Jews from around the world. It provided refuge for many European Jews after the Holocaust, with 25% of the population in the 1960s being Holocaust survivors. If the Jewish people had had a state of their own in the 1930s, many more Jews would have been saved from the Holocaust. Israel survived an attack by 4 neighboring armies when it declared Independence in 1948. Israel has achieved peace with both Egypt and Newly formed Israel built an army to Jordan after multiple wars. defend itself with 50% of the soldiers being Holocaust survivors. In 1979 Israel withdrew from the Sinai Peninsula in return for normalising relations and demilitarisation of the Sinai. This agreement ended any prospect of another general Arab-Israeli war and has been a cornerstone of regional stability for nearly 40 years. Israel and Jordan signed a peace agreement in 1994. Not only did Israel achieve a successful emergency rescue of 14,500 Ethiopian Jews, nearly the entire Jewish population of Ethiopia, in under 36 hours, but it also broke the world record of carrying the most passengers on a 747 or any flying vehicle in the world.