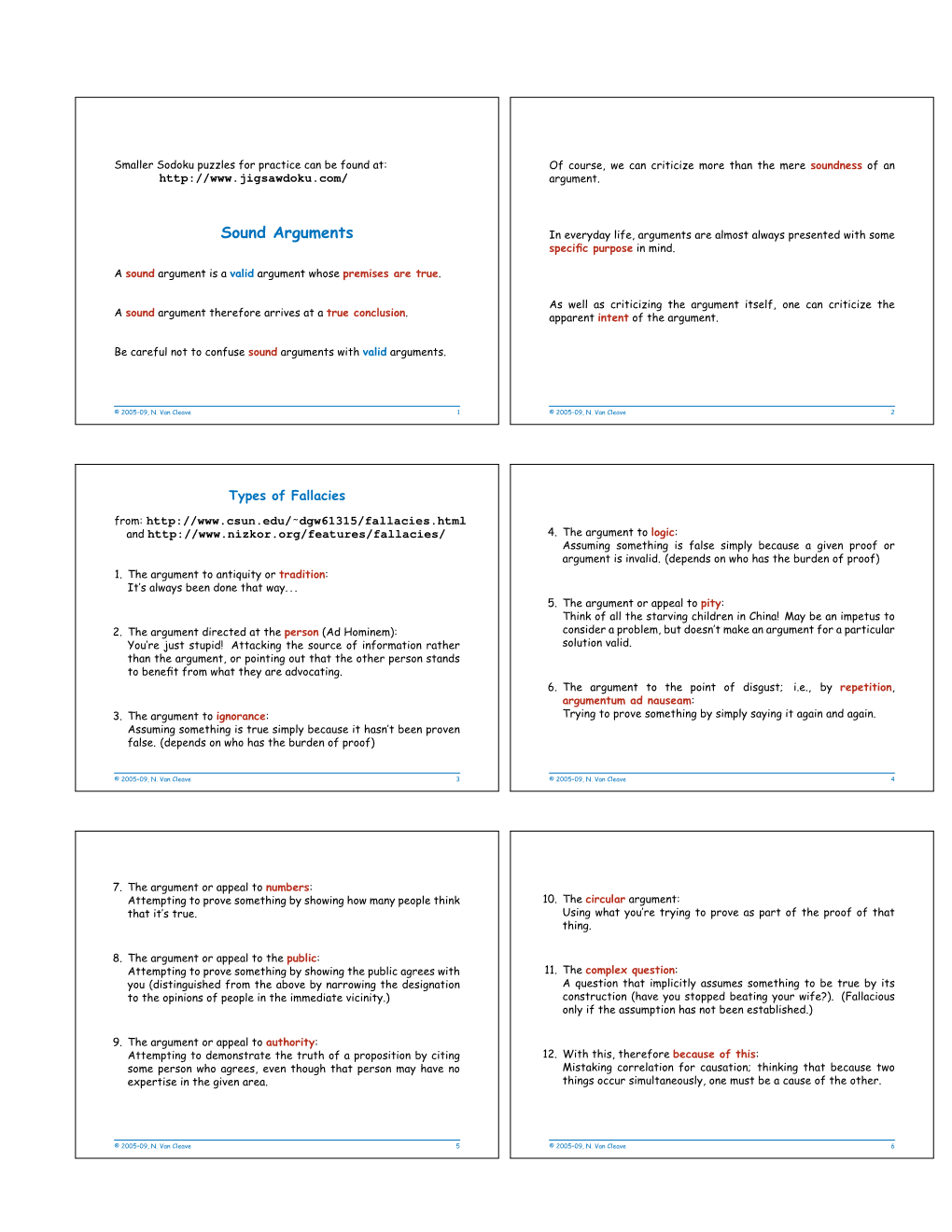

Sound Arguments in Everyday Life, Arguments Are Almost Always Presented with Some Specific Purpose in Mind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Naturalistic Fallacy and Natural Law Methodology

The Naturalistic Fallacy and Natural Law Methodology W. Matthews Grant It is customary to divide contemporary natural law theorists-at least those working broadly within the Thomistic tradition-into two main camps. In one camp are those such as John Finnis, Germain Grisez and Robert George, who deny that a natural law ethics need base itself on premises supplied by a methodologically prior philosophical anthropol ogy. According to these thinkers, practical reason, when reflecting on experience and considering possible ends of action, grasps in a non-in ferential act of understanding certain basic goods that ought to be pursued. Since these goods are not deduced, demonstrated, or derived from prior premises, they provide a set of self-evident or per se nota primary pre cepts from which all other precepts of the natural law may be derived. Because these primary precepts or basic goods are self-evident, natural law theorizing need not wait on the findings of anthropologists and phi losophers of human nature. 1 A rival school of natural law ethicists, comprised of such thinkers as Russell Bittinger, Ralph Mcinerny, Henry Veatch andAnthony Lisska, rejects the claims of Finnis and his colleagues for the autonomy of natural law I. For major statements and defenses of this position see John Finnis, Natural Law and Natural Rights (Oxford: Oxford University Press, I980); Germain Grisez, The Way of the Lord Jesus~ vol. I, Christian Moral Principles (Chicago: Franciscan Herald Press, I983);. Robert P. George, "Recent Criticism of Natural Law -

Ethics of the (Un)Natural

Ethics of the (un)natural Start date 22nd January 2017 Time 10:00am – 16:45pm Venue Madingley Hall Madingley Cambridge Tutor Anna Smajdor Course code 1617NDX055 Director of Programmes Emma Jennings Public Programme Coordinator, Clare Kerr For further information on this course, please contact [email protected] or 01223 746237 To book See: www.ice.cam.ac.uk or telephone 01223 746262 Tutor biography Anna is Associate Professor of Practical Philosophy at the University of Oslo. Prior to that, she was Ethics Lecturer at Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia. She has been offering philosophy courses at ICE for several years on themes related to her research interests, such as 'Ethics of the (Un)natural' in 2016/17. When not teaching at ICE, Anna spends her time at the University of Oslo and collaborating with colleagues at the University of Umeå in Sweden, where she is part of a research project- 'Close personal relationships-children and the family'. University of Cambridge Institute of Continuing Education, Madingley Hall, Cambridge, CB23 8AQ www.ice.cam.ac.uk Course programme 09:30 Terrace bar open for pre-course tea/coffee 10:00 – 11:15 Session 1 – Unnatural practices 11:15 Coffee 11:45 – 13:00 Session 2 – “Our niggardly stepmother” 13:00 Lunch 14:00 – 15:15 Session 3 – The naturalistic fallacy 15:15 Tea 15:30 – 16:45 Session 4 – Reasoning with nature 16:45 Day-school ends University of Cambridge Institute of Continuing Education, Madingley Hall, Cambridge, CB23 8AQ www.ice.cam.ac.uk Course syllabus Aims: To engage students in a critical analysis of the ways in which concepts of nature are used in moral reasoning To explore the degree to which the ‘natural fallacy’ sweeps aside the possibility of reasoning from nature To analyse several key bioethical questions (animal research, conservation, human/animal chimaeras) on which concepts of nature have a bearing Content: This course will analyse the relationship between morality and nature in the context of key bioethical concerns, e.g. -

Couch's “Physical Alteration” Fallacy: Its Origins And

COUCH’S “PHYSICAL ALTERATION” FALLACY: ITS ORIGINS AND CONSEQUENCES Richard P. Lewis,∗ Lorelie S. Masters,∗∗ Scott D. Greenspan*** & Chris Kozak∗∗∗∗ I. INTRODUCTION Look at virtually any Covid-19 case favoring an insurer, and you will find a citation to Section 148:46 of Couch on Insurance.1 It is virtually ubiquitous: courts siding with insurers cite Couch as restating a “widely held rule” on the meaning of “physical loss or damage”—words typically in the trigger for property-insurance coverage, including business- income coverage. It has been cited, ad nauseam, as evidence of a general consensus that all property-insurance claims require some “distinct, demonstrable, physical alteration of the property.”2 Indeed, some pro-insurer decisions substitute a citation to this section for an actual analysis of the specific language before the court. Couch is generally recognized as a significant insurance treatise, and courts have cited it for almost a century.3 That ∗ Partner, ReedSmith LLP, New York. ∗∗ Partner, Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP, Washington D.C. *** Senior Counsel, Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP, New York. ∗∗∗∗ Associate, Plews Shadley Racher & Braun, LLP, Indianapolis. 1 10A STEVEN PLITT, ET AL., COUCH ON INSURANCE 3D § 148:46. As shown below, some courts quote Couch itself, while others cite cases citing Couch and merely intone the “distinct, demonstrable, physical alteration” language without citing Couch itself. Couch First and Couch Second were published in hardback books (with pocket parts), in 1929 and 1959 respectively. As explained below (infra n.5), Couch 3d, a looseleaf, was first published in 1995.. 2 Id. (emphasis added); Oral Surgeons, P.C. -

10 Fallacies and Examples Pdf

10 fallacies and examples pdf Continue A: It is imperative that we promote adequate means to prevent degradation that would jeopardize the project. Man B: Do you think that just because you use big words makes you sound smart? Shut up, loser; You don't know what you're talking about. #2: Ad Populum: Ad Populum tries to prove the argument as correct simply because many people believe it is. Example: 80% of people are in favor of the death penalty, so the death penalty is moral. #3. Appeal to the body: In this erroneous argument, the author argues that his argument is correct because someone known or powerful supports it. Example: We need to change the age of drinking because Einstein believed that 18 was the right age of drinking. #4. Begging question: This happens when the author's premise and conclusion say the same thing. Example: Fashion magazines do not harm women's self-esteem because women's trust is not damaged after reading the magazine. #5. False dichotomy: This misconception is based on the assumption that there are only two possible solutions, so refuting one decision means that another solution should be used. It ignores other alternative solutions. Example: If you want better public schools, you should raise taxes. If you don't want to raise taxes, you can't have the best schools #6. Hasty Generalization: Hasty Generalization occurs when the initiator uses too small a sample size to support a broad generalization. Example: Sally couldn't find any cute clothes in the boutique and couldn't Maura, so there are no cute clothes in the boutique. -

On Appeals to Nature and Their Use in the Public Controversy Over Genetically Modified Organisms Andrei Moldovan

Document generated on 09/25/2021 12:45 a.m. Informal Logic On Appeals to Nature and their Use in the Public Controversy over Genetically Modified Organisms Andrei Moldovan Volume 38, Number 3, 2018 Article abstract In this paper I discuss appeals to nature, a particular kind of argument that has URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1057048ar received little attention in argumentation theory. After a quick review of the DOI: https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v38i3.5050 existing literature, I focus on the use of such arguments in the public controversy over the acceptabil-ity of genetically-modified organisms in the See table of contents food industry. Those who reject this biotechnology invoke its unnatural character. Such arguments have re-ceived attention in bioethics, where they have been analyzed by distinguishing different meanings that “nature” and Publisher(s) “natural” might have. I argue that in many such appeals to nature the main deficiency of these arguments is semantic, in particular, that these words Informal Logic cannot be assigned a determi-nate meaning at all. In doing so, I rely on semantic externalism, a widely accepted theory of linguistic meaning. ISSN 0824-2577 (print) 2293-734X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Moldovan, A. (2018). On Appeals to Nature and their Use in the Public Controversy over Genetically Modified Organisms. Informal Logic, 38(3), 409–437. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v38i3.5050 Copyright (c), 2018 Andrei Moldovan This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. -

Scientific Method DRAFT

SCIENTIFIC METHOD John Staddon DRAFT Scientific Method DRAFT CONTENTS Preface 3 Chapter 1: Basic Science: Induction 6 Chapter 2: Experiment 21 Chapter 3: Null Hypothesis Statistical Testing 31 Chapter 4: Social Science: Psychology 51 Chapter 5: Social Science: Economics 67 Chapter 6: Behavioral Economics 84 Chapter 7: ‘Efficient’ markets 105 Chapter 8: Summing up 124 Acknowledgements 131 2 Scientific Method DRAFT Preface The most profound ideas cannot be understood except though the medium of examples. Plato, Philebus Most people assume that science can answer every question. Well, not every , perhaps, but every question except matters of faith or morals – although a few atheistical fundamentalists would include those things as well. How many people are killed or hurt by secondhand tobacco smoke each year? How should you discipline your children? What is the best diet? The questions are important and confident answers are forthcoming from experts. The confidence is often unjustified. There are limits to science, both practical and ethical. But for many social and biomedical questions, demand for simple answers tends to silence reservations. Flawed and even fallacious claims meet a need and get wide circulation. “Don’t know” doesn’t get a look in! When conclusive science is lacking, other influences take up the slack: faith, politics, suspicion of authority. Even when the facts are clear, many will ignore them if the issue is an emotional one – fear for their children’s safety, for example. The anti-vaccine crusade launched in a discredited study by British doctor Andrew Wakefield in 1998 is still alive in 2017, partly because most people do not understand the methods of science and no longer trust experts. -

Naturalness and Unnaturalness in Contemporary Bioethics Anna Smajdor 57 Artikkel Samtale & Kritikk Spalter Brev

ARTIKKEL SAMTALE & KRITIKK SPALTER BREV Meta-ethical and methodological considerations The is/ought distinction and the naturalistic fallacy FRA FORSKNINGSFRONTEN Nature appears in bioethics in a number of guises and con- There is no great invention, from fire to flying, which has texts. At the most basic level, people may feel that it is mo- not been hailed as an insult to some god. But if every rally wrong to alter, distort or subvert natural processes. physical and chemical invention is a blasphemy, every NATURALNESS AND Leon Kass, for example, argues that an intuitive recoiling biological invention is a perversion. There is hardly one from interventions such as cloning that distort or frag- which, on first being brought to the notice of an observer ment the natural processes of reproduction, is a powerful from any nation which had not previously heard of their UNNATURALNESS IN indicator that such interventions are unethical (1998:3– existence, would not appear to him as indecent and un- 61). These are perhaps the most obvious occasions when natural. (Haldane 1924) nature plays an explicit role in informing moral reaso- CONTEMPORARY ning in bioethics. However, there are many other ways in Peter Singer and Deane Wells state categorically that “… which nature colours the concepts and themes employed there is no valid argument from ‘unnatural’ to ‘wrong’ in bioethical deliberation. For example, bioethicists may (2006:9-26). Similar views can be found in the work of BIOETHICS be concerned with the natural world, or nature, especially many bioethicists. A report on the ethics of grafting hu- in terms of our moral responsibility to the environment. -

Warnings, Disclaimers, and Literary Theory

Reading the Product: Warnings, Disclaimers, and Literary Theory Laura A. Heymann* I. INTRODUCTION Few television commercials for alcohol end with the protagonist slumped unconscious on the couch, falling off a bar stool, or driving a car into a telephone pole. To the contrary, as many of us have experienced, advertising writes a very different narrative: that purchase and consumption of the advertised beverage will make one more attractive, expand one's social circle, and yield unbridled happiness. It is a story that, the advertiser hopes, will inspire consumers to choose its beverage during the next trip to the store; in this vein, the true protagonist of the commercial is the brand. Marketing scholars and, to a lesser extent, trademark scholars have increasingly viewed advertising and branding through the lens of literary theory, recognizing that consumers interpret communications about a product using many of the same tools that they use to interpret other kinds of texts.1 But this lens has not been similarly focused on an important counternarrative: the warning or disclaimer (such as "Caution: This product may contain nuts" on a candy bar or "Not authorized by * Associate Professor of Law, College of William & Mary - Marshall-Wythe School of Law. Many thanks to Jessica Silbey and the participants in the "Reasoning from Literature" panel at the 2010 AALS Annual Meeting, where this work was first presented. Many thanks also to Peter Alces, Mark Badger, Barton Beebe, Deborah Gerhardt, and Lisa Ramsey for helpful comments; to the staff of the Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities for their very thoughtful and perceptive edits; and to Brad Bartels and Katharine Kruk Spindler for research assistance. -

Propaganda Techniques

Propaganda Techniques Adapted from Wikipedia Ad hominem ( “to the person”) A Lan phrase which has come to mean aacking your opponent, as opposed to aacking their arguments. Ex. "Your fashion opinion isn't valid; you can't even afford new shoes." Ad nauseam (“to the point of nausea”) or Repe==on This argument approach uses =reless repe==on of an idea. An idea, especially a simple slogan, that is repeated enough =mes, may begin to be taken as the truth. This approach works best when media sources are limited and controlled by the propagator. Ex. Appeal to authority Appeals to authority; cite prominent figures to support a posi=on, idea, argument, or course of ac=on. Ex. “Even the President has smoked pot!” Appeal to fear Appeals to fear seek to build support by ins=lling anxie=es and panic in the general populaon. Ex. Joseph Goebbels exploited Theodore N. Kaufman's Germany Must Perish! to claim that the Allies sought the exterminaon of the German people. Appeal to prejudice • Using loaded or emo=ve terms to aach value or moral goodness to believing the proposion. • Ex: "Any hard-working taxpayer would have to agree that those who do not work, and who do not support the community do not deserve the community's support through social assistance." Bandwagon Bandwagon and "inevitable-victory" appeals aempt to persuade the target audience to join in and take the course of ac=on that "everyone else is taking”. Black-and-White fallacy • Presen=ng only two choices, with the product or idea being propagated as the be?er choice. -

Evolutionary Ethics? Substantiators, Skeptics, and Moral Realism

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-04-30 Evolutionary Ethics? Substantiators, Skeptics, and Moral Realism Jimenez, Kieran Chad Jimenez, K. C. (2013). Evolutionary Ethics? Substantiators, Skeptics, and Moral Realism (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26002 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/662 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Evolutionary Ethics? Substantiators, Skeptics, and Moral Realism by Kieran Jimenez A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2013 © Kieran Jimenez 2013 Abstract Hardly a week passes without new findings emerging from evolutionary psychology regarding how our view of morality has been influenced by our biological evolution. Evolutionary ethics is a normative project built upon these scientific insights. Evolutionary ethicists fall into two groups: substantiators or skeptics. Substantiators believe moral ideas can now be scientifically proven. Skeptics believe there are no moral truths because morality is just a biological adaptation. I believe the project of evolutionary ethics is misconceived. I argue that both the substantiators and the skeptics fail to show the direct relevance of biology to ethics. -

PHI 1100: Ethics & Critical Thinking

PHI 1100: Ethics & Critical Thinking Sessions 23 & 24 May 5th & 7th, 2020 Evaluating Arguments: Sufficient Evidence, Reasonable Inferences, Respectful Argumentation 1 A good argument persuades readers/listeners by giving us adequate reason to believe that its conclusion is true. Ø Here are four basic criteria which will all be satisfied by a good argument: I. The premises are true. II. The premises provide sufficient evidence to believe that the conclusion is true. III. The conclusion follows logically from the truth of the premises. IV. It demonstrates the author’s respect for their readers/listeners. So far, we have discussed fallacies that involve: • the use of language to present false or misleading evidence • the use of statistics to present false or misleading evidence, insufficient evidence, or to make faulty inferences – This week we’ll go into more detail about fallacies involving the use of language to present 2 insufficient evidence or to make faulty inferences. A good argument persuades readers/listeners by giving us adequate reason to believe that its conclusion is true. III. The conclusion follows logically from the truth of the premises. • Fallacies that fail to satisfy this criterion of a good argument make faulty inferences: – they draw a conclusion that isn’t guaranteed (or extremely likely) to be true even if the premises are true. Ønon sequitur (Latin for ‘it doesn’t follow’) = when an argument draws a conclusion that just isn’t supported by the reasoning they have provided. ]P1] Dorothy is wearing red shoes today. [C] Obviously, red is Dorothy’s favorite color. » Many of the fallacies we’ll consider this week can be classified as subtypes of non sequiturs, • which draw particular types of conclusions from particular types of inadequate evidence. -

The Naturalizing Error

Douglas Allchin & Alexander J. Werth The Naturalizing Error Douglas Allchin Minnesota Center for the Philosophy of Science University of Minnesota Minneapolis MN 55455 e-mail: [email protected] phone: 651.603.8805 Alexander J. Werth Department of Biology Hampden-Sydney College Hampden Sydney VA 23901 Abstract We describe an error type that we call the naturalizing error: an appeal to nature as a self-justified description dictating or limiting our choices in moral, economic, political, and other social contexts. Normative cultural perspectives may be subtly and subconsciously inscribed into purportedly objective descriptions of nature, often with the apparent warrant and authority of science, yet not be fully warranted by a systematic or complete consideration of the evidence. Cognitive processes may contribute further to a failure to notice the lapses in scientific reasoning and justificatory warrant. By articulating this error type at a general level, we hope to raise awareness of this pervasive error type and to facilitate critiques of claims that appeal to what is “natural” as inevitable or unchangeable. Keywords error types; naturalizing error; naturalistic fallacy; public understanding of science; social construction of science The Naturalizing Error Abstract We describe an error type that we call the naturalizing error: an appeal to nature as a self-justified description dictating or limiting our choices in moral, economic, political, and other social contexts. Normative cultural perspectives may be subtly and subconsciously inscribed into purportedly objective descriptions of nature, often with the apparent warrant and authority of science, yet not be fully warranted by a systematic or complete consideration of the evidence.