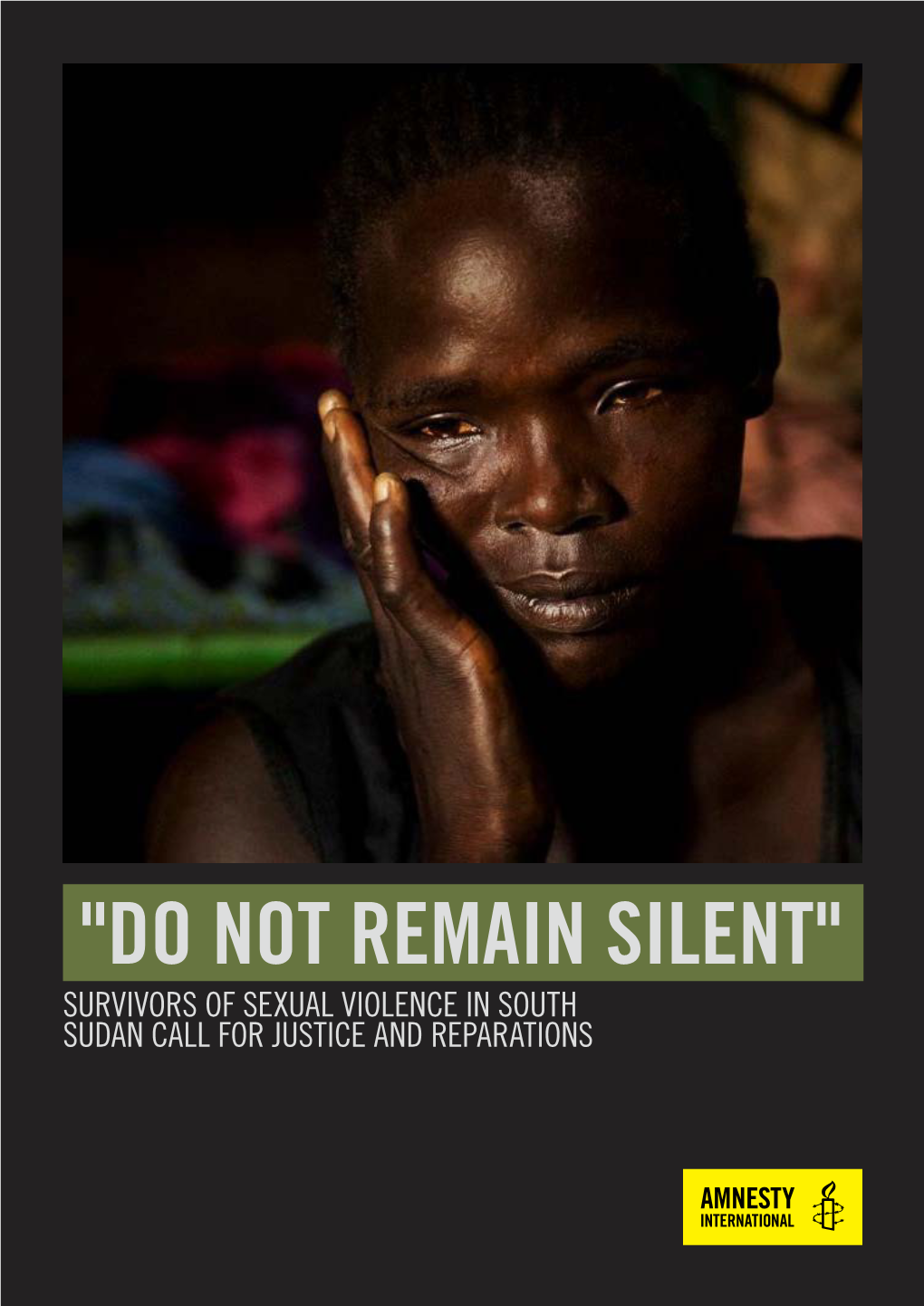

"Do Not Remain Silent"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Informal Peace Efforts

CMI BRIEF 2018:7 1 NUMBER 7 CMI BRIEF NOVEMBER 2018 Photo courtesy of Isis-WICCE Women’s informal peace efforts: Grassroots activism in South Sudan AUTHORS South Sudanese women have been grossly under-represented Helen Kezie-Nwoha in formal peace negotiations. However, they have been active Juliet Were in informal peacebuilding at the local level where peace means rebuilding society. Such informal peacebuilding is radically different to formal peace negotiations where male warlords and political leaders in new positions of power divide the spoils of war. This brief describes women’s informal peace work in South Sudan, and shows the extensive and valuable, but often unrecognized work that women’s organizations do. We also look at how women’s roles in formal processes are informed by women’s informal work. 2 CMI BRIEF 2018:7 Methodology In this study, we conducted individual and focus groups discussions with women activists from groups located in South Sudan and in Uganda. We completed 21 individual interviews, eight focus group discussions (with a total of 111 women) and two community meetings with 90 women in all. The interviews were conducted between June 2017 and July 2018. Fighting between different warring factions caused delays and made it difficult to access study locations. The long road to peace Women’s role in formal peace processes South Sudan gained independence from Sudan on 9 July 2011. Since then, South Sudan has been marred by internal conflicts. What started as a power struggle Women’s under-representation in peace between President Salva Kiir and his deputy, former negotiations is the norm rather than Vice President Riek Machar, quickly devolved into a war the exception. -

DRC DDG South Sudan Organogram 2016

Nhialdiu Payam Rubkona County // Unity // South Sudan Rapid Site Assessment GPS N 29.68332 // E 09.02619 April 2019 CURRENT CONTEXT LOCATION The DRC RovingCCCM team covers priority Beyond Bentiu Response (BBR) counties within Unity State; Rubkona, Guit and Koch. The team carries out CCCM activities using an area based approach, working through the CCCM cluster to disseminate information. Activities in Nhialdiu on 13th and 14th March 2019 included a multi-sector needs assessment in the area, analysis of displacement situation, mapping of structures and services and meeting with community representatives. For more information, contact Anna Salvarli [email protected] and Ezekiel Duol [email protected] COMMUNITY LEADERSHIP STRUCTURE TOTAL MEMBERS: 25 13 Female 12 Male SITE POPULATION & DISPLACEMENT CONTEXT HUMANITARAIN ACTORS STATE Unity State There are 5 humanitarian actors whose services are accessed in Nhialdiu Payam from the surrounding villages with COUNTY Rubkona County inadequate services. There have been decreased static humanitarian intervention due to insecurity incidents in 2018 in the area. The key services provided and noted were the following: PAYAM Nhialdiu Payam POPULATION 3,262 HHs , 15,036 individuals (IOM DTM March 2019) SITE TYPE Spontaneous returnees (integrated with host community) CCCM DRC (roving team from Bentiu) SITE MANAGER Self managed EDUCATION Mercy Corps (standards 1 to 4, 201 pupils; 120 female, 81 male) FSL None (WHH food assistance) DISPLACEMENT POPULATION HEALTH CASS (National Organization) There is an estimated total of over 800 individuals returnees to Nhialdiu who came between November NUTRITION Cordaid 2018 and March 2019 as per the information given by the local authority. -

South Sudan Country Portfolio

South Sudan Country Portfolio Overview: Country program established in 2013. USADF currently U.S. African Development Foundation Partner Organization: Foundation for manages a portfolio of 9 projects and one Cooperative Agreement. Tom Coogan, Regional Director Youth Initiative Total active commitment is $737,000. Regional Director Albino Gaw Dar, Director Country Strategy: The program focuses on food security and Email: [email protected] Tel: +211 955 413 090 export-oriented products. Email: [email protected] Grantee Duration Value Summary Kanybek General Trading and 2015-2018 $98,772 Sector: Agro-Processing (Maize Milling) Investment Company Ltd. Location: Mugali, Eastern Equatoria State 4155-SSD Summary: The project funds will be used to build Kanybek’s capacity in business and financial management. The funds will also build technical capacity by providing training in sustainable agriculture and establishing a small milling facility to process raw maize into maize flour. Kajo Keji Lulu Works 2015-2018 $99,068 Sector: Manufacturing (Shea Butter) Multipurpose Cooperative Location: Kajo Keji County, Central Equatoria State Society (LWMCS) Summary: The project funds will be used to develop LWMCS’s capacity in financial and 4162-SSD business management, and to improve its production capacity by establishing a shea nut purchase fund and purchasing an oil expeller and related equipment to produce grade A shea butter for export. Amimbaru Paste Processing 2015-2018 $97,523 Sector: Agro-Processing (Peanut Paste) Cooperative Society (APP) Location: Loa in the Pageri Administrative Area, Eastern Equatoria State 4227-SSD Summary: The project funds will be used to improve the business and financial management of APP through a series of trainings and the hiring of a management team. -

Promoting Peace and Resilience in Unity State, South Sudan

BRIEF / FEBRUARY 2021 Promoting peace and resilience in Unity state, South Sudan The town of Bentiu, located in Rubkona County, is the comprising 11,529 households.1 Although people capital of the oil-rich Unity state and is predominately living in the PoC site are provided with protection and inhabited by the Nuer people. A series of waterways and humanitarian assistance, they still face challenges swamps cover large parts of the state and these provide including economic hardship, being targeted by armed pasture in the dry season for animals belonging to Nuer groups, violent crime, revenge killings inside the PoC and Dinka pastoralists, as well as other pastoralist site, and outbreaks of disease as a result of the crowded groups from neighbouring Sudan who migrate with conditions in which they live. In July 2020, UNMISS their animals into South Sudan during dry seasons in initiated consultations about its intention to re-designate search of grazing land and water. Unity state also sits the PoC sites in the country to IDP camps and hand over on some of the largest oil deposits in South Sudan and a responsibility of these camps to the government of South considerable amount of petroleum-related activity takes Sudan. People living in the Bentiu PoC site expressed place in and around Bentiu. The production of oil has concern at this plan – while conditions inside the contributed to fuelling conflicts in the state, resulting in camp are very poor, IDPs fear the threat of violence and displacement and environmental degradation. insecurity outside the PoCs if responsibility is transferred. -

South Sudan Village Assessment Survey

IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY DATA COLLECTION: August-November 2019 COUNTIES: Bor South, Rubkona, Wau THEMATIC AREAS: Shelter and Land Ownership, Access and Communications, Livelihoods, Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies, Health, WASH, Education, Protection 1 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN CONTENTS RUBKONA COUNTY OVERVIEW 15 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 15 RETURN PATTERNS 15 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 16 KEY FINDINGS 17 Shelter and Land Ownership 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Access and Communications 17 LIST OF ACRONYMS 3 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Livelihoods 18 BACKROUND 6 Health 19 WASH 19 METHODOLOGY 6 Education 20 LIMITATIONS 7 Protection 20 WAU COUNTY OVERVIEW 8 BOR SOUTH COUNTY OVERVIEW 21 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 8 RETURN PATTERNS 8 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 21 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 9 RETURN PATTERNS 21 KEY FINDINGS 10 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 22 KEY FINDINGS 23 Shelter and Land Ownership 10 Access and Communications 10 Shelter and Land Ownership 23 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 10 Access and Communications 23 Livelihoods 11 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 23 Health 12 Livelihoods 24 WASH 13 Health 25 Protection 13 Education 26 Education 14 WASH 27 Protection 27 2 3 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN LIST OF ACRONYMS AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome -

Annex 2 USAID South Sudan Gender Based Violence Prevention And

USAID/SOUTH SUDAN GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE PREVENTION AND RESPONSE ROADMAP SEPTEMBER 2019 Contract No.: AID-OAA-TO-17-00018 September 26, 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Banyan Global. Contract No.: AID-OAA-TO-17-00018 Submitted to: USAID/South Sudan DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) or the United States Government. Recommended Citation: Gardsbane, Diane and Aluel Atem. USAID/South Sudan Gender-Based Violence Prevention and Response Roadmap. Prepared by Banyan Global. 2019. Cover photo credit: USAID Back Cover photo credit: USAID USAID/SOUTH SUDAN GENDER- BASED VIOLENCE PREVENTION AND RESPONSE ROADMAP SEPTEMBER 2019 Contract No.: AID-OAA-TO-17-00018 4 USAID/SOUTH SUDAN GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE PREVENTION AND RESPONSE ROADMAP CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 9 1.1 ROADMAP OBJECTIVE 9 1.2 STRUCTURE OF ROADMAP 9 2. INTEGRATING GBV IN THE USAID/SOUTH SUDAN OPERATIONAL FRAMEWORK 11 2.1 THEORY OF CHANGE 11 2.2 INTEGRATING THE THEORY OF CHANGE INTO THE USAID/SOUTH SUDAN OPERATIONAL FRAMEWORK 12 3. GBV PREVENTION AND RESPONSE ROADMAP PROGRAMMATIC GUIDING PRINCIPLES 19 4. BRINGING IT ALL TOGETHER – GBV PREVENTION, MITIGATION AND RESPONSE ROADMAP 27 5. GUIDELINES TO ADDRESS GBV IN MONITORING, EVALUATION AND LEARNING 39 6. KEY RESOURCES 41 ANNEX A: GBV PREVENTION AND RESPONSE ROADMAP LITERATURE REVIEW 57 ANNEX B: PROGRAM AND DONOR REPORT 73 ANNEX C: GBV LITERACY TRAINING 95 ANNEX D: LIST OF KEY DOCUMENTS CONSULTED 99 ANNEX E. -

UNICEF SOUTH SUDAN COUNTRY OFFICE Rapid Response Team

UNICEF SOUTH SUDAN COUNTRY OFFICE Rapid Response Team Report Location (State/County/Payam/etc): Unity/Rubkona/Nhialdiu Date of the Mission: 16-25 October 2014 1 Name & Title of Kibrom Tesfaselassie - Nutrition Specialist UNICEF Team Leader 2 Names & Titles (with 1. Elizabeth Mukheb, Child protection UNIDO – Tel No. 0927328405; [email protected] org/depart/section) 2. Hari Vinathan, Nutrition Consultant, UNICEF - Tel no. 0955492068; [email protected] of other members of 3. Luel Deng, Education officer, UNICEF - Tel no. 0955158685; [email protected] 4. Okwera Joseph Okot, Health consultant - Tel no. 0959001482; [email protected] the team 5. Paul Okullu, WASH officer, International Aids Services (IAS), Tel no. 0955963274 3 Sites visited Nhialdiu HQ, Nhialdiu payam, Rubkona County, Unity State GPS; virtually centre of Nhial-Diu:- Latitude : N 09001’19.91’’ Longitude : E 029040’45.44’’ Altitude : 428.4m Information and Data collected 4 General General information about the mission site Information Number of registered people: 40,000 based on WFP verification process for previously given registration card last July. Number of households: over 14,000 including IDPs Total number of children under five (if available): Not Applicable as there was no new registration. Total number of children under 18 years (if available): NA Humanitarian situation and needs (IDPs, last time they received support, who is in control of the area etc.): Nhialdiu is a Payam of Rubkona County consisting of 16 Bomas southwest of Bentiu town approximately 40 km away. As per WFP, this mission covers four/five Payams including IDPs, with a total of population above 40,000. -

1 AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O

AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: +251 11 551 7700 / +251 11 518 25 58/ Ext 2558 Website: http://www.au.int/en/auciss Original: English FINAL REPORT OF THE AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON SOUTH SUDAN ADDIS ABABA 15 OCTOBER 2014 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I ..................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER II .................................................................................................................. 34 INSTITUTIONS IN SOUTH SUDAN .............................................................................. 34 CHAPTER III ............................................................................................................... 110 EXAMINATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND OTHER ABUSES DURING THE CONFLICT: ACCOUNTABILITY ......................................................................... 111 CHAPTER IV ............................................................................................................... 233 ISSUES ON HEALING AND RECONCILIATION ....................................................... -

Local Needs and Agency Conflict: a Case Study of Kajo Keji County, Sudan

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 11, Issue 1 | Fall 2009 Local Needs and Agency Conflict: A Case Study of Kajo Keji County, Sudan RANDALL FEGLEY Abstract: During Southern Sudan’s second period of civil war, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) provided almost all of the region’s public services and greatly influenced local administration. Refugee movements, inadequate infrastructures, food shortages, accountability issues, disputes and other difficulties overwhelmed both the agencies and newly developed civil authorities. Blurred distinctions between political and humanitarian activities resulted, as demonstrated in a controversy surrounding a 2004 distribution of relief food in Central Equatoria State. Based on analysis of documents, correspondence and interviews, this case study of Kajo Keji reveals many of the challenges posed by NGO activity in Southern Sudan and other countries emerging from long-term instability. Given recurrent criticisms of NGOs in war-torn areas of Africa, agency operations must be appropriately geared to affected populations and scrutinized by governments, donors, recipients and the media. A Critique of NGO Operations Once seen as unquestionably noble, humanitarian agencies have been subject to much criticism in the last 30 years.1 This has been particularly evident in the Horn of Africa. Drawing on experience in Ethiopia, Hancock depicted agencies as bureaucracies more intent on keeping themselves going than helping the poor.2 Noting that aid often allowed despots to maintain power, enrich themselves and escape responsibility, he criticized their tendency for big, wasteful projects using expensive experts who bypass local concerns and wisdom and do not speak local languages. He accused their personnel of being lazy, over-paid, under-educated and living in luxury amid their impoverished clients. -

A Strategy for Achieving Gender Equality in South Sudan

SPECIAL REPORT January 28, 2014 A Strategy for Achieving Gender Equality in South Sudan Jane Kani Edward ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study is a product of the Sudd Institute Gender Fellowship in South Sudan awarded to me to conduct research from June to August 2013. The fellowship was made possible by a generous grant from the United States Institute for Peace (USIP). I am grateful to the Sudd Institute and USIP for making this endeavor possible. Numerous individuals and institutions have made the fellowship and fieldwork particularly successful. I am extremely thankful to government officials, primary school administrators, and members of the faculty of Juba University, who welcomed me to their offices and homes, accepted to be interviewed, and provided important documents used in the analysis of the collected data. Special thanks also to members of Lo’bonog Women Group, Rabita Salam Wa Muhaba, and the Ayiki Farmers Association, who shared their experiences of organizing and the challenges they face. Their participation was critically important in making this study successful. Finally, I would like to thank all the staff of the Sudd Institute in Juba, South Sudan for making my research experience during my visit a success. © The Sudd Institute || SPECIAL REPORT | 2 ABBREVIATIONS AEOs Agricultural Extension Officers CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement ECOSOC Economic and Social Council GAD Gender and Development GBV Gender-Based Violence GOSS Government of Southern -

LC SS 706 A1 EEQ 20130301.Pdf

pp p ! ! p ! p (! ! !( 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E 35°0'0"E Gwalla Awan KolnyangAluk Katanich Titong Munini Beru ! R . K Wowa ang en Logoda N Rigl Chilimun N " " 0 0 p' Bor South County ' 0 Pibor County Lowelli Katchikan River Bellel Kichepo 0 ° Maktiweng J O N G L E I ° 6 Kaigo 6 Lochiret R. Naro Kenamuke Swamp R Ngechele . S Neria u p Kanopir Natibok Kabalatigo i r i ( B Moru Kimod a Rongada h r Yebisak e g l- n Tombi J o e b b l Shogle e a l) Buka h C . Gwojo-Adung Kassangor R Baro ! E T H I O P I A Moru Kerri KURON Kuron Gigging p Bojo-Ajut Gemmaiza ! Karn Ethi Kerkeng Moru Ethi Nakadocwa Poko Wani Terekeka County Kobowen Swamp Borichadi Bokuna Poko Kassengo Selemani Pagar Nabwel Wani Mika Chabong Tukara C E N T R A L p River Nakua p Kenyi E Q U A T O R I A Moru Angbin Mukajo Gali Owiyabong Kursomba Lotimor Bulu Koli Kalaruz Awakot Katima Waha ! Akitukomoi River Gera Tumu Nanyangachor Nyabongi Napalap ! Namoropus Natilup Swamp ) it Wanyang Kangitabok Lomokori le Eyata Moru Kolinyagkopil il ! Terakeka ri Lozut Lomongole t iti o (! S L Magara p R. ( n Umm Gura Mwanyakapin a p y l Abuilingakine Lomareng Plateau a Dogora R Ngigalingatun k o . L Jelli L o p Rambo Djie Navi . Lokodopotok Nyaginei Kangeleng p R Biyara Nai A o Kworijik Kangibun Lomuleye Katirima t o Simsima Badigeru Swamp River Lokuja Losagam k Musha Lukwatuk Pass Doinyoro East p o p l Balala Legeri Buboli Kalopedet Pongo River Lokorowa Watha Peth Hills Bume E A S T E R N E Q U A T O R I A Lokidangoai Nawitapal Lopokori Lokomarukest Kolobeleng Yakara Dogatwan Nomogonjet Kagethi ! Mogos Bala Pool Lapon County Lotakawa Kanyabu Moru Ethi Donyiro West Donyiro Cliff Kedowa Kothokan a l l i Chokagiling t Karakamuge o Mangalla Bwoda L Mediket Kaliapus Nyangatom !( . -

Frontlines September/October 2011

FRONTLINES WWW.USAID.GOV SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2011 TWO SUDANS THE SEPARATION OF AFRICA’S LARGEST COUNTRY AND THE ROAD AHEAD > A GLOBAL EDUCATION FOOTPRINT TAKES SHAPE > EGYPT SHAKES UP THE CLASSROOM > Q&A WITH REP. NITA LOWEY Sudan & South Sudan/Education Edition INSIGHTS From Administrator Dr. Rajiv Shah A few weeks before South Sudan’s skills, making it more likely they will day of independence, I had the oppor- eventually drop out. tunity to visit the region and meet a These failures leave developing na- HE WORLD welcomed its group of children who were learning tions without the human and social newest nation when South English and math in a USAID-supported capital needed to advance and sustain Sudan officially gained its primary education program. The stu- development. They deprive too many inde pendence on July 9. After dents ranged in ages from 4 to 14. individuals of the skills they need as Tover two decades of war and suffering, Many of the older students have lived productive members of their commu- a peace agree ment between north and through a period of displacement, vio- nities and providers for their families. south Sudan paved the way for South lence, and trauma. This was likely the Across the world, our education pro- Sudanese to fulfill their dreams of self- very first opportunity they had to re- grams emphasize a special focus on determination. The United States played ceive even a basic education. disadvantaged groups such as women an important role in helping make this When you see American taxpayer and girls and those living in remote moment possible, and today we remain money being effectively used to provide areas.