Bearded Ladies Walking on the Brooklyn Bridge David G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southeastern Association of Law Schools 2015 Annual Conference Boca Raton Resort and Club | Boca Raton, FL | July 27 - August 2, 2015

Southeastern Association of Law Schools 2015 Annual Conference Boca Raton Resort and Club | Boca Raton, FL | July 27 - August 2, 2015 CONFERENCE PROGRAM Southeastern Association of Law Schools 2015 Annual Conference Boca Raton Resort and Club | Boca Raton, FL | July 27 - August 2, 2015 CONFERENCE PROGRAM Southeastern Association of Law Schools | 2015 Annual Conference Boca Raton Resort and Club | Boca Raton, FL | July 27 - August 2, 2015 Table of Contents PG CONTENTS 3 SEALS 2014-15 Board of Trustees and Officers 4 SEALS 2014-15 Staff 5 A Message from the President 6 Program Format Overview 8 Schedule of Events – Monday, July 27, 2015 17 Schedule of Events – Tuesday, July 28, 2015 27 Schedule of Events – Wednesday, July 29, 2015 34 Schedule of Events – Thursday, July 30, 2015 43 Schedule of Events – Friday, July 31, 2015 52 Schedule of Events – Saturday, August 1, 2015 61 Schedule of Events – Sunday, August 2, 2015 65 SEALS Member Schools 68 Index of Schools 86 Index of Participants 104 SEALS Committees & Coordinators Southeastern Association of Law Schools | 2015 Annual Conference Boca Raton Resort and Club | Boca Raton, FL | July 27 - August 2, 2015 2014-2015 Board of Trustees and Officers President Trustee Term Ending 2015 Professor Ellen Podgor Professor Jonathan Cardi Stetson University School of Law Wake Forest University School of Law [email protected] [email protected] President-Elect Trustee Term Ending 2016 Professor Jeffrey Hirsch Professor Nancy Levit University of North Carolina School of Law University of Missouri-Kansas City [email protected] School of Law [email protected] Executive Director Professor Russell L. -

Reserve Your 1L Outlines Now, So a Hardcopy Is Waiting for You On-Campus Next Fall

The Nation’s #1 Law School Prep Course Reserve Your 1L Outlines Now, So A Hardcopy Is Waiting For You On-Campus Next Fall BARBRI has created law school outlines that make preparing for classes and exams easier than ever. BARBRI 1L law school outlines to ensure you’re not missing important points of law, elements of legal analysis, and cases from the classes you’re studying. Our 1L course outlines also help students kickstart the outlining process and reinforce their grasp of the substantive rules (the black letter law) so they can apply the law during class discussions and on final exams. 1L Courses Included: Reserve Your Free 1L Outlines: • Civil Procedure • Criminal Law lawpreview.com/1L-outlines • Constitutional Law • Real Property • Contracts • Torts Prep for Law School with Law Preview | Learn More at LawPreview.com The Nation’s #1 Law School Prep Course START LAW SCHOOL WITH $10,000 “One Lawyer Can Change the World” Scholarship Apply to Win $10,000 Toward Your 1L Tuition Law schools, BARBRI Law Preview believes that, in the right hands, a law degree can change the world. We also know that getting a legal education is an expensive journey. Getting a legal education can be an expensive journey. That’s why we’re giving one future change agent a $10,000 scholarship to help pay for the first year of law school. First Prize: $10,000 Second Prize: $5,000 Eight Runners Up: $1,000 To apply, visit lawpreview.com/10k-now. “Not only is it financially rewarding but also winning the scholarship is a huge stamp of approval towards my life’s mission and my ambition of being a lawyer who hopes to change the world. -

THE CALIFORNIA BAR EXAM Teddy Hook Director of Legal Education [email protected]

THE CALIFORNIA BAR EXAM Teddy Hook Director of Legal Education [email protected] HOW DO I GET ADMITTED TO THE CA BAR? FOUR REQUIREMENTS 1. Register as a Student with the CA State Bar 2. Complete the Moral Character Application 3. Pass the Multistate Professional Responsibility Exam (MPRE) 4. Register for and Pass the CA Bar Exam REQUIREMENT #1: REGISTRATION Register as a student with the CA State Bar https://www.calbarxap.com/applications/calbar/ California_Bar_Registration/ Fee: $119 – Credit – Debit #2: MORAL CHARACTER APPLICATION WHAT IS IT? The ultimate background check to make sure you are morally fit for the practice of law WHAT INFO DO I HAVE TO PROVIDE? • Answered questionnaire (very extensive) with supporting documents • References • Live Scan Fingerprinting (in state)/Card Processing (out of state) – Purpose is to check you for a criminal record – Only valid for 90 days; after that the FBI deletes them #2: MORAL CHARACTER APPLICATION HOW LONG DOES IT TAKE TO PROCESS? A minimum of 180 days, but UP TO 10 months SO WHEN SHOULD I SUBMIT IT? • CA Bar recommends 10 months before you want to be admitted to the CA Bar. • If you’re taking the taking the Summer 2017 CA Bar • Results come out in November • Passing applicants admitted as soon as late November • Count back 10 months from November –submit your moral character application in Jan/Feb HOW MUCH DOES IT COST? $551 #3: MULTISTATE PROFESSIONAL RESPONSIBILITY EXAM (MPRE) WHAT IS IT? WHEN CAN I TAKE IT? • 2 hour, 60 question test – 50 questions count • March 18, 2017 – 10 are experimental -

Final Programme

Final Programme Follow us OFFICIAL CORPORATE SUPPORTER @IBAevents #IBARome Expert and professional advice since 1975 The law firm Studio Legale Tributario Fantozzi & Associati was established in 1975 by Augusto Fantozzi, a lawyer and full professor of tax law at the ‘’La Sapienza’’ and ‘’LUISS’’ Universities in Rome. Professor Fantozzi was the Italian Minister for Finance and the Minister of Foreign Trade between 1995 and 1998, and he is a member of the Board of Directors and the Board of Statutory Auditors of several leading Italian companies and multinational corporations. The Firm has offices in Rome, Milan and Bologna. With 8 Senior Partners, all lawyers or chartered accountants, and more than 30 legal professionals, the Firm is highly specialised in tax law, and as such provides clients with advice on Italian and international fiscal law, and assists them in tax litigation. Thanks to the years of experience of its partners and legal professionals, the Firm can offer clients full support in resolving tax and corporate issues, both nationally and internationally. Over the years the Firm has dealt with the fiscal aspects of numerous important corporate and financial operations carried out by public and private companies, banks, finance companies and insurance undertakings, and has become their go-to adviser on ordinary and extraordinary tax matters. ROMA | MILANO | BOLOGNA www.fantozzieassociati.com Follow us CONTENTS Contents @IBAevents #IBARome Introduction by the President of the IBA 5 IBA Management Board and IBA Staff 6 Opening -

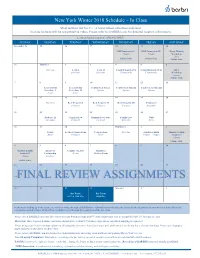

Final Review Assignments

New York Winter 2018 Schedule – In Class Most lectures last for 3½ - 4 hours unless otherwise indicated. In-class lectures will be presented via video. Please refer to BARBRI.com for detailed location information. Lectures shaded in gray are ONLINE ONLY. SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY December 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 MBE Immersion I* MBE Immersion II* Essay Writing 7 hours 7 hours Workshop Sims Online Only Online Only Online Only 31 January 1 2 3 4 5 6 No Class Torts I Torts II Constitutional Law I Constitutional Law II MPT Schechter Schechter Chemerinsky Chemerinsky Workshop Lisnek Online Only 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Federal Civil Federal Civil Contracts & Sales I Contracts & Sales II Contracts & Sales III Procedure I Procedure II Epstein Epstein Epstein Freer Freer 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 No Class Real Property I Real Property II Real Property III Evidence I Franzese Franzese Franzese Alexander 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Evidence II Criminal Law Criminal Procedure Family Law Wills Alexander Cornwell Cornwell Schechter Beyer 28 29 30 31 February 1 2 3 Trusts Secured Transactions Corporations No Class Simulated MBE Simulated MBE Beyer Franzese Freer 9:30am – 4:30pm Analysis I 8 hours Online Only 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Simulated MBE Agency & Conflict of Laws Simulated Analysis II Partnership Jordan Written Exam 8 hours Kaufman Online Only 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 FINAL REVIEW ASSIGNMENTS 25 26 27 28 March 1 2 3 Bar Exam Bar Exam MPT & MEE Day MBE Day In the weeks leading up to the exam, you will be working through a Final Review of all subjects by following the personalized assignments in your Personal Study Plan and reviewing recorded lectures which will be available to you through the completion of the bar exam. -

Preliminary Programme

Preliminary Programme Follow us OFFICIAL CORPORATE SUPPORTER @IBAevents #IBARome Our social event sponsors WELCOME PARTY INDIVIDUAL TAX AND PRIVATE CLIENT COMMITTEE NETWORKING SOCIAL EVENT ENYO LAW DISPUTES. NO CONFLICTS. INTERNATIONAL CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS COMMITTEE NETWORKING SOCIAL EVENT ANTI-CORRUPTION, BUSINESS CRIME, CRIMINAL LAW AND WAR CRIMES COMMITTEE NETWORKING SOCIAL EVENT INTERNATIONAL FRANCHISING COMMITTEE NETWORKING SOCIAL EVENT ARBITRATION COMMITTEE RECEPTION AND DINNER NETWORKING SOCIAL EVENT INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW ART, CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS AND HERITAGE COMMITTEE NETWORKING SOCIAL EVENT LAW COMMITTEE NETWORKING SOCIAL EVENT YOUNG LAWYERS ‘NIGHT OUT’ CORPORATE AND M&A COMMITTEE RECEPTION AND NETWORKING SOCIAL EVENT All sponsorship packages include a complimentary delegate pass to the conference. However, it should be noted that complimentary delegates’ passes, given as part of these packages, cannot be assigned to speakers, panellists, Chairs or co-chairs, members of the press or adjudicators. All sponsorship options and their benefits, are non-exclusive and non-negotiable. Should you have any questions regarding the available sponsorship options at the conference in Sydney, please do not hesitate to contact me via email at [email protected] or telephone on +44 (0)20 7842 0090. Follow us CONTENTS Contents @IBAevents #IBARome IBA staff Introduction by the President of the IBA 5 In addition to the Association’s senior officers, many staff from the IBA offices will be attending the conference -

Final Review Assignments

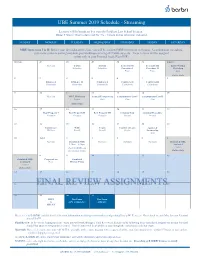

UBE Summer 2019 Schedule - Streaming Lectures will be broadcast live from the Fordham Law School location. Time: 9:30am | Most lectures last for 3½ - 4 hours unless otherwise indicated. SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY MBE Immersion I & II: Before your first substantive class, you will be assigned MBE Immersion (12 hours): A combination test-taking, systematic problem solving and strategies workshop covering all 7 MBE subjects. These lectures will be assigned online only in your Personal Study Plan (PSP). May 26 27 28 29 30 31 June 1 No Class Torts I Torts II Federal Civil Federal Civil Essay Writing Schechter Schechter Procedure I Procedure II Workshop Freer Freer Sims Online Only 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Evidence I Evidence II Contracts I Contracts II Contracts III Counseller Counseller Calandrillo Calandrillo Calandrillo 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 No Class MPT Workshop Secured Transactions Constitutional Law I Constitutional Law II Lisnek Moll Thai Thai Online Only 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Real Property I Real Property II Real Property III Criminal Law Criminal Procedure Franzese Franzese Franzese Noreuil Noreuil 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Family Law Wills Trusts Conflict of Laws Agency & Wallace Powell Powell Jordan Partnership Moll 30 July 1 2 3 4 5 6 No Class Simulated MBE No Class No Class No Class Simulated MBE 9:30am – 4:30pm Analysis I 8 hours Check BARBRI.com for location details Online Only 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Simulated MBE Corporations Simulated Analysis II Freer Written Exam 8 hours Online Only 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 FINAL22 REVIEW23 24 ASSIGNMENTS25 26 27 28 29 30 31 REST Bar Exam Bar Exam & MPT & MEE Day MBE Day RELAX Please refer to BARBRI.com for detailed location information including room numbers and parking/library/Wi-Fi access. -

Law Society of Scotland Annual Conference 2019 Handbook

Supported by Law Society of Scotland Annual Conference 2019 Annual Conference 2019 Welcome It is my great pleasure to welcome you to We have a packed agenda for you, and I hope this year’s Annual Conference. you will get a lot out of the conversations you hear and take part in today. We have a fantastic As we celebrate the 70th year of the Law line-up of speakers who will challenge you Society of Scotland it is the perfect time to and inspire you in equal measure. reflect on both the successes of the past, and the future challenges ahead. Do get involved. Take part in the conversations in the room. Make new connections, and This year’s conference theme ‘Leading Legal renew old ones. This is your conference, and Excellence’ gives us the scope to look at a you’ll get out of it what you put in. wide range of issues, offering speakers and breakout sessions which will appeal to our I look forward to meeting and speaking with whole audience. as many of you as possible during today. It is fair to say that this has been an interesting Enjoy and welcome to the 2019 Annual year to work in the legal profession. Never Conference. before has the public eye been focused on the courts in quite the same way as we’ve witnessed over the past few months. This year’s annual conference gives us space to reflect on what has been happening, and what that means for the future of the profession, and the future of the country as Brexit presents challenges for us as lawyers John Mulholland and for the businesses we work for. -

Texas Summer 2020 Course Sequence

Texas Summer 2020 Course Sequence Below is the order in which subjects will be presented. Dates are estimated and will vary as the online schedule is flexible and based on your own personal progress. Most substantive lectures last for 3 - 4 hours unless otherwise indicated. MBE Immersion I & II: Before your first substantive class, you will be assigned MBE Immersion (12 hours): A combination test-taking, systematic problem solving and strategies workshop covering all seven MBE subjects. • Essay Writing Workshop • MPT Workshop Week of May 24 • Torts I-II • Corporations • Criminal Law • TX and Federal Criminal Procedure & Evidence I-III Week of May 31 • Federal Civil Procedure I-II • Texas Civil Procedure • Wills I Week of June 7 • Wills II, Estate Administration & Guardianship • Trusts and Federal Estate & Gift Tax • Real Property I-III • Oil & Gas Week of June 14 • Contracts & Sales I-II • Consumer Law • Evidence I-II • Constitutional Law I-II Week of June 21 • Simulated MBE (7 hours) • Simulated MBE (MSE) Review & Analysis • Commercial Paper • Secured Transactions Week of June 28 • Community Property • Family Law • Federal Income Taxations • Bankruptcy • Agency & Partnership Week of July 5 • Simulated Written Exam • Texas Procedure & Evidence Workshop (optional/additional charge) • Final Review In the weeks leading up to the exam, you will work through a Final Review July 10 – 26 of all subjects by following the assignments in your Personal Study Plan (PSP). Your PSP and all online lectures will remain available to you through the completion of the bar exam. July 27 Rest & Relax July 28 – 30 • Bar Examination Your Personal Study Plan™ (PSP) will be available in early May. -

Teaching Remedial Problem-Solving Skills to a Law School's Underperforming Students

Texas A&M University School of Law Texas A&M Law Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 9-2015 Teaching Remedial Problem-Solving Skills to a Law School's Underperforming Students John F. Murphy Texas A&M University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar Part of the Legal Education Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Legal Writing and Research Commons Recommended Citation John F. Murphy, Teaching Remedial Problem-Solving Skills to a Law School's Underperforming Students, 16 Nev. L.J. 173 (2015). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/925 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING REMEDIAL PROBLEM-SOLVING SKILLS TO A LAW SCHOOL'S UNDERPERFORMING STUDENTS John F. Murphy* INTRODUCTION ......... 174 I. DEFINING THE PROBLEM: UNDERPERFORMING STUDENTS WHO FAIL TO MASTER BASIC PROBLEM-SOLVING SKILLS IN THE FIRST YEAR OF LAW SCHOOL. ......................................... 174 II. WORKING TOWARD A SOLUTION: "THE ART OF LAWYERING" CLASS .......................................................... 175 III. COURSE OBJECTIVES AND METHODS......................... ...... 177 IV. SPECIAL CHALLENGES PRESENTED BY THE ART OF LAWYERING ...... 179 V. THE ART OF LAWYERING TOOLBOX ......................... ...... 182 A. Hill & Vukadin's Legal Analysis: 100 Exercisesfor Mastery .... 182 B. Multistate Performance Tests .................. ....... 182 C. Multiple-Choice Questions................... .......... 184 D. The Case Grid: A GraphicalTool to FacilitateAnalogical Reasoning......................................... 187 1. The Case Grid: How It Works and How to Use It............... -

2015-2016 Revised Catalog & Student Handbook

APPALACHIAN SCHOOL OF LAW 2015-2016 Revised Catalog & Student Handbook (effective February 15, 2016) 1169 Edgewater Drive Grundy, VA 24614 276-935-4349 Toll-Free: 1-800-895-7411 FAX: 276-935-8261 Website: www.asl.edu This catalog and handbook (hereafter catalog) is published by Appalachian School of Law (ASL) based on information as of February 2016, and contains information concerning campus life, career preparation, academic policies, and course offerings. Effective in 2016, the catalog is moving to digital publication and will only be available on the website. ASL reserves the right to make alterations in course offerings and academic policies without prior notice in order to further the institution's purpose; however, an email will be sent to the faculty, staff, and student body using ASL listservs each time a substantive policy update is published to the website. Information in this catalog is a guide and not an offer of a contract. It is not intended to, nor does it contain all policies and regulations that relate to students. Students are expected to familiarize themselves with the academic policies contained in the catalog. Failure to do so does not excuse students from the requirements and regulations described herein. Appalachian School of Law admits students without regard to age, race, color, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, disability, religion, political affiliation, veteran status, or national and ethnic origin to all the rights, privileges, programs, and activities generally accorded or made available to students at the school. It does not discriminate on the basis of age, race, color, gender, sexual orientation, disability, religion, political affiliation, veteran status or national and ethnic origin in administration of its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, and/or other school administered programs. -

Syracuse University College of Law Library Selected New Acquisitions: June 2017

Syracuse University College of Law Library Selected New Acquisitions: June 2017 HB75 .A833 2017 Law Library Ashford, History of economic thought : a concise Business Expert Press, Economics History. Robert, 1943 treatise for business, law, and public policy / 2017. Robert Ashford, Stefan J. Padfield. HB75 .A833 2017 Law Library Ask at Reference Desk Special Collections Ashford, History of economic thought : a concise Business Expert Press, Economics History. Robert, 1943 treatise for business, law, and public policy / 2017. Robert Ashford, Stefan J. Padfield. JK1726 .A4 Law Library American affairs. American Affairs Economic policy. Foundation, Inc. 2017 Political culture United States. Political science. International relations. JV6483 .I55429 2017 Law Library Immigration, emigration, and migration / New York University Emigration and immigration law United States. edited by Jack Knight. Press, [2017] Audio KF240 .B467 2016 Law Library Reserves Audio Collection Berring, Legal research / by Professor Bob Berring. West Academic Legal research United States. Robert C., Second edition. Publishing, [2016] KF240 .P65 2017 Law Library Reserves Pollman, Legal research examples & explanations / Wolters Kluwer, [2017] Legal research United States. Terrill, 1948 Terrill Pollman (Professor of Law William S. Boyd School of Law University of Nevada, Las Vegas) ; Jeanne Frazier Price (Associate Dean of Academic Affairs, William S. Boyd School of Law, University of Nevada, Las KF246 .B46 2017 Law Library Reference Prince, Mary Prince's dictionary of legal abbreviations : a William S. Hein & Co., Annotations and citations (Law) United States Miles, reference guide for attorneys, legal Inc., 2017. Dictionaries. secretaries, paralegals, and law students / by Mary Miles Prince. Seventh edition. Law United States Abbreviations Dictionaries. Audio KF297 .H4 2008 Law Library Reserves Audio Collection Hermann, R.