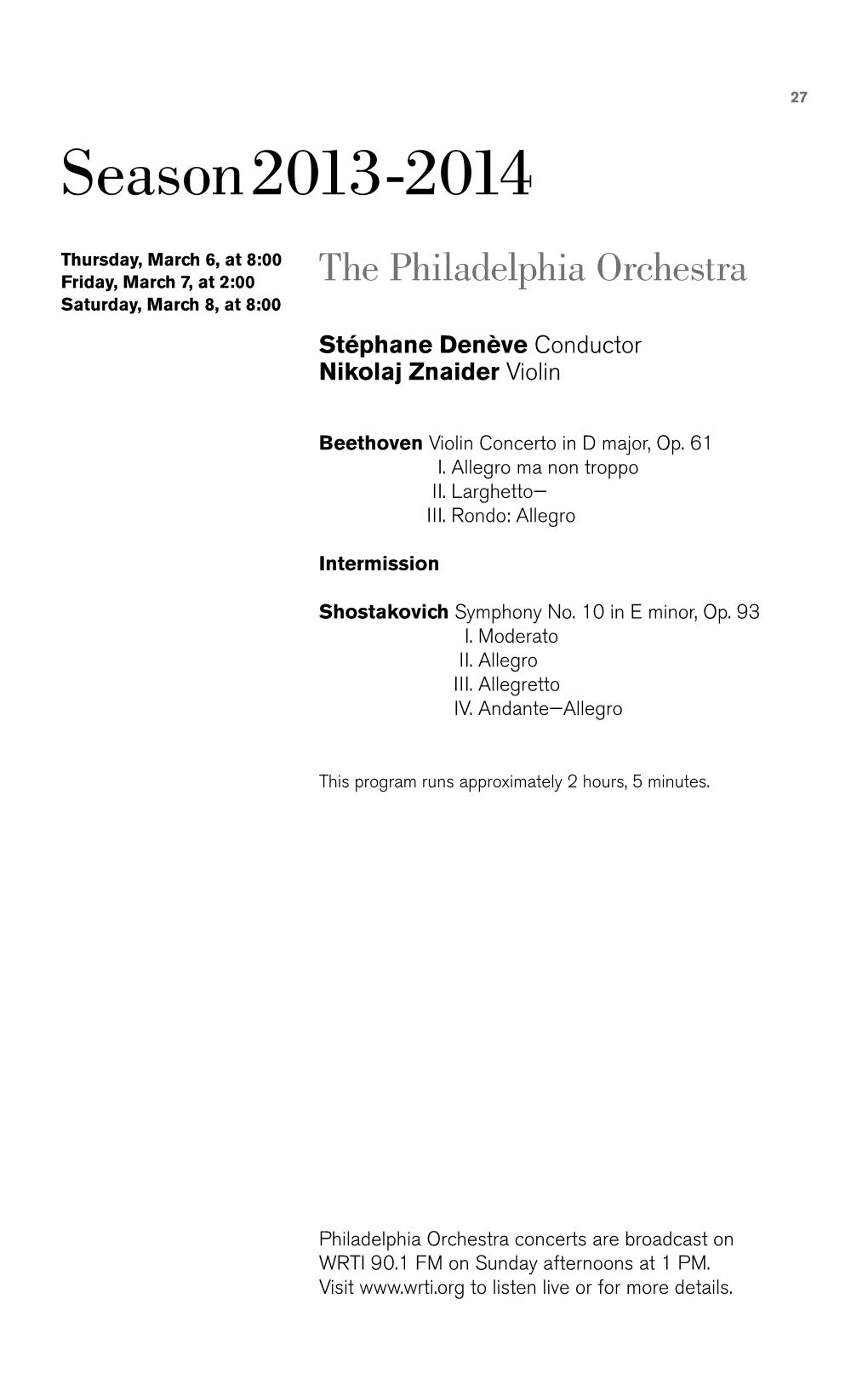

Season 2013-2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nikolaj Znaider Remarquables Et Restitués Grâce Aux Techniques Les Plus Modernes De L’Enregistrement Haute-Définition

LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus Nikolaj Znaider remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvresdu répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Violin Concertos Nos 4 & 5 Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns herein: lso.co.uk LSO0807 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) Track list Violin Concerto No 4 in D major, K218 (1775) Mozart Violin Concerto No 4 in D major, K218 Violin Concerto No 5 in A major, K219 (1775) 1 I. Allegro 8’37’’ 2 II. Andante cantabile 6’20’’ Nikolaj Znaider conductor / violin 3 III. -

The St. Louis Symphony Orchestra and Music Director Stéphane Denève Announce Fall Programming for the 2021/2022 Season

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE [June , ] Contacts: St. Louis Symphony Orchestra: Eric Dundon [email protected], C'D-*FG-D'CD National/International: NiKKi Scandalios [email protected], L(D-CD(-D(MD THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA AND MUSIC DIRECTOR STÉPHANE DENÈVE ANNOUNCE FALL PROGRAMMING FOR THE 2021/2022 SEASON Highlights of offerings from September 17-December 5, 2021, include: • The return of full orchestral performances led by Music Director Stéphane Denève at Powell Hall featuring repertoire spanning genre and time that celebrates the resilience of the human spirit. • Denève opens the classical season with two programs at Powell Hall. The season opener includes the first SLSO performances of Jessie Montgomery’s Banner and Anna Clyne’s Dance alongside Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 4. In his second weeK, Denève leads the SLSO in the string orchestra version of Caroline Shaw’s Entr’acte, Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question, Christopher Rouse’s Rapture, and Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 with pianist Yefim Bronfman. • The SLSO and Denève continue their deep commitment to music and composers of today, performing works by Thomas Adès, Karim Al-Zand, William Bolcom, Jake Heggie, James Lee III, Jessie Montgomery, Caroline Shaw, Carlos Simon, Outi Tarkiainen, Joan Tower, and the U.S. premiere of Anna Clyne’s PIVOT. • Other highlights of Denève’s fall programs include performances of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, Dmitri ShostaKovich’s Symphony No. 5, and collaborations with pianist VíKingur Ólafsson in his first SLSO appearance and violinist Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider. • The highly anticipated return of the free Forest Park concert, which welcomes thousands of St. -

Nikolaj Znaider in 2016/17

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 29 May 2016 7pm Barbican Hall BEETHOVEN VIOLIN CONCERTO Beethoven Violin Concerto London’s Symphony Orchestra INTERVAL Elgar Symphony No 2 Sir Antonio Pappano conductor Nikolaj Znaider violin Concert finishes approx 9.20pm 2 Welcome 29 May 2016 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A very warm welcome to this evening’s LSO ELGAR UP CLOSE ON BBC iPLAYER concert at the Barbican. Tonight’s performance is the last in a number of programmes this season, During April and May, a series of four BBC Radio 3 both at the Barbican and LSO St Luke’s, which have Lunchtime Concerts at LSO St Luke’s was dedicated explored the music of Elgar, not only one of to Elgar’s moving chamber music for strings, with Britain’s greatest composers, but also a former performances by violinist Jennifer Pike, the LSO Principal Conductor of the Orchestra. String Ensemble directed by Roman Simovic, and the Elias String Quartet. All four concerts are now We are delighted to be joined once more by available to listen back to on BBC iPlayer Radio. Sir Antonio Pappano and Nikolaj Znaider, who toured with the LSO earlier this week to Eastern Europe. bbc.co.uk/radio3 Following his appearance as conductor back in lso.co.uk/lunchtimeconcerts November, it is a great pleasure to be joined by Nikolaj Znaider as soloist, playing the Beethoven Violin Concerto. We also greatly look forward to 2016/17 SEASON ON SALE NOW Sir Antonio Pappano’s reading of Elgar’s Second Symphony, following his memorable performance Next season Gianandrea Noseda gives his first concerts of Symphony No 1 with the LSO in 2012. -

Chicago Presents Symphony Muti Symphony Center

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI zell music director SYMPHONY CENTER PRESENTS 17 cso.org1 312-294-30008 1 STIRRING welcome I have always believed that the arts embody our civilization’s highest ideals and have the power to change society. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra is a leading example of this, for while it is made of the world’s most talented and experienced musicians— PERFORMANCES. each individually skilled in his or her instrument—we achieve the greatest impact working together as one: as an orchestra or, in other words, as a community. Our purpose is to create the utmost form of artistic expression and in so doing, to serve as an example of what we can achieve as a collective when guided by our principles. Your presence is vital to supporting that process as well as building a vibrant future for this great cultural institution. With that in mind, I invite you to deepen your relationship with THE music and with the CSO during the 2017/18 season. SOUL-RENEWING Riccardo Muti POWER table of contents 4 season highlight 36 Symphony Center Presents Series Riccardo Muti & the Chicago Symphony Orchestra OF MUSIC. 36 Chamber Music 8 season highlight 37 Visiting Orchestras Dazzling Stars 38 Piano 44 Jazz 10 season highlight Symphonic Masterworks 40 MusicNOW 20th anniversary season 12 Chicago Symphony Orchestra Series 41 season highlight 34 CSO at Wheaton College John Williams Returns 41 CSO at the Movies Holiday Concerts 42 CSO Family Matinees/Once Upon a Symphony® 43 Special Concerts 13 season highlight 44 Muti Conducts Rossini Stabat mater 47 CSO Media and Sponsors 17 season highlight Bernstein at 100 24 How to Renew Guide center insert 19 season highlight 24 Season Grid & Calendar center fold-out A Tchaikovsky Celebration 23 season highlight Mahler 5 & 9 24 season highlight Symphony Ball NIGHT 27 season highlight Riccardo Muti & Yo-Yo Ma 29 season highlight AFTER The CSO’s Own 35 season highlight NIGHT. -

A B C a B C D a B C D A

24 go symphonyorchestra chica symphony centerpresent BALL SYMPHONY anne-sophie mutter muti riccardo orchestra symphony chicago 22 september friday, highlight season tchaikovsky mozart 7:00 6:00 Mozart’s fiery undisputed queen ofviolin-playing” ( and Tchaikovsky’s in beloved masterpieces, including Rossini’s followed by Riccardo Muti leading the Chicago SymphonyOrchestra season. Enjoy afestive opento the preconcert 2017/18 reception, proudly presents aprestigious gala evening ofmusic and celebration The Board Women’s ofthe Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Gala package guests will enjoy postconcert dinner and dancing. rossini Suite from Suite 5 No. Concerto Violin to Overture C P s oncert reconcert Reception Turkish The Sleeping Beauty Concerto. The SleepingBeauty William Tell conducto The Times . Anne-Sophie Mutter, “the (Turkish) William Tell , London), performs London), , media sponsor: r violin Overture 10 Concerts 10 Concerts A B C A B 5 Concerts 5 Concerts D E F G H I 8 Concerts 5 Concerts E F G H 5 Concerts 6 Conc. 5 Concerts THU FRI FRI SAT SAT SUN TUE 8:00 1:30 8:00 2017/18 8:00 8:00 3:00 7:30 ABCABCD ABCDAAB Riccardo Muti conductor penderecki The Awakening of Jacob 9/23 9/26 Anne-Sophie Mutter violin tchaikovsky Violin Concerto schumann Symphony No. 2 C A 9/28 9/29 Riccardo Muti conductor rossini Overture to William Tell 10/1 ogonek New Work world premiere, cso commission A • F A bruckner Symphony No. 4 (Romantic) A Alain Altinoglu conductor prokoFIEV Suite from The Love for Three Oranges Sandrine Piau soprano poulenc Gloria Michael Schade tenor gounod Saint Cecilia Mass 10/5 10/6 Andrew Foster-Williams 10/7 C • E B bass-baritone B • G Chicago Symphony Chorus Duain Wolfe chorus director 10/26 10/27 James Gaffigan conductor bernstein Symphonic Suite from On the Waterfront James Ehnes violin barber Violin Concerto B • I A rachmaninov Symphonic Dances Sir András Schiff conductor mozart Serenade for Winds in C Minor 11/2 11/3 and piano bartók Divertimento for String Orchestra 11/4 11/5 A • G C bach Keyboard Concerto No. -

Mozart: Violin Concertos Nos 1, 2 & 3

Nikolaj Znaider Violin Concertos Nos 1, 2 & 3 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) Violin Concerto No 1 in B-flat major, K207 (1773) Violin Concerto No 2 in D major, K211 (1775) Violin Concerto No 3 in G major, K216, “Straßburg” (1775) Nikolaj Znaider conductor / violin London Symphony Orchestra Recorded live in DSD 128fs, 18 December 2016 (No 1), and in DSD 256fs, 7 December 2017 (Nos 2 & 3) at the Barbican, London Andrew Cornall producer Classic Sound Ltd recording, editing and mastering facilities Jonathan Stokes for Classic Sound Ltd balance engineer, audio editing, mixing and mastering Neil Hutchinson for Classic Sound Ltd recording engineer © 2018 London Symphony Orchestra Ltd, London, UK P 2018 London Symphony Orchestra Ltd, London, UK 2 Track list Mozart Violin Concerto No 1 in B-flat major, K207 1 I. Allegro moderato 6’41’’ 2 II. Adagio 6’41’’ 3 III. Presto 5’49’’ Mozart Violin Concerto No 2 in D major, K211 4 I. Allegro moderato 8’25’’ 5 II. Andante 7’40’’ 6 III. Rondeau: Allegro 4’18’’ Mozart Violin Concerto No 3 in G major, K216, "Straßburg" 7 I. Allegro 8’26’’ 8 II. Adagio 7’33’’ 9 III. Rondeau: Allegro 6’06’’ Total 61’39’’ 3 more than 20 symphonies and seven operas, for Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart instance, and his ready grasp of the skills of structural (1756–1791) clarity, effective orchestral writing and affecting lyrical invention are certainly on display here. What Violin Concerto No 1 in B-flat major, is missing, perhaps, is the more relaxed playful K207 (1773) note that can be heard in the other violin concertos; good-natured though it may be, this is in some Although the prevailing image of Mozart the ways a rather serious and formal first attempt. -

Stéphane Denève Commits to Serve As Music Director of the St

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE [March , ] Contacts: St. Louis Symphony Orchestra: Eric Dundon [email protected], (,D-+FG-D,(D National/International: NiKKi Scandalios [email protected], L)D-(D)-D)MD STÉPHANE DENÈVE COMMITS TO SERVE AS MUSIC DIRECTOR OF THE ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THROUGH THE 2025/2026 SEASON Extension highlights mission-driven collaboration and continued artistic and institutional stability for the nation’s second-oldest orchestra (March , WUWX, St. Louis, MO) – Today, the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra announced a four-year extension of Stéphane Denève’s contract as Music Director. The extended contract runs through the end of the SLSO’s +)+V/+)+G season, which will be Denève’s seventh as Music Director. Denève’s initial three-year contract began With the / season following one season as Music Director Designate. His long partnership With the SLSO began in , When he led the SLSO for the first of many engagements as a guest conductor prior to his appointment as Music Director. The announcement comes as Denève leads the SLSO in the return of live concerts With audiences at PoWell Hall, the first since early November +)+. Steven Finerty, Chair of the SLSO Board of Trustees, said, “Stéphane is the ideal partner for the SLSO. He brings a profound musicianship and a deep understanding to his role, Which he infuses With great creativity, good humor, humility, and humanity. Along With President and CEO Marie-Hélène Bernard—with whom he has developed a remarKable partnership—Stéphane has helped hone the SLSO as an artistically excellent, community-minded, and financially responsible organization for years to come.” Marie-Hélène Bernard, SLSO President and CEO, said, “In the time Stéphane has been Music Director, he has continued to build on the celebrated artistic legacy of the SLSO While advancing the next era of the orchestra. -

[email protected] MANFRED HONECK to Conduct

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 28, 2018 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5700; [email protected] MANFRED HONECK To Conduct SIBELIUS’s Violin Concerto with NIKOLAJ ZNAIDER as Soloist Mr. Honeck’s Arrangement of DVOŘÁK’s Rusalka Fantasy Selections from TCHAIKOVSKY’s Sleeping Beauty May 3–5 and 8, 2018 NIKOLAJ ZNAIDER To Make New York Philharmonic Conducting Debut TCHAIKOVSKY’s Symphony No. 1, Winter Dreams ELGAR’s Cello Concerto with JIAN WANG in Philharmonic Subscription Debut May 10–12, 2018 Manfred Honeck will return to the New York Philharmonic to conduct Sibelius’s Violin Concerto, with Nikolaj Znaider as soloist; Mr. Honeck’s own arrangement of Dvořák’s Rusalka Fantasy, orchestrated by Tomáš Ille; and selections from Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty, Thursday, May 3, 2018, at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, May 4 at 11:00 a.m.; Saturday, May 5 at 8:00 p.m.; and Tuesday, May 8 at 7:30 p.m. The following week, Nikolaj Znaider will make his New York Philharmonic conducting debut leading Elgar’s Cello Concerto, with Jian Wang in his subscription debut, and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 1, Winter Dreams, Thursday, May 10, 2018, at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, May 11 at 8:00 p.m.; and Saturday, May 12 at 8:00 p.m. Manfred Honeck and Nikolaj Znaider previously collaborated on Sibelius’s Violin Concerto with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (PSO), in Pittsburgh and on tour in 2012. Mr. Znaider also conducted the PSO that year in music by Elgar, Wagner, and Mozart. Manfred Honeck completed his arrangement of Dvořák’s Rusalka Fantasy in 2015 and led its first performances with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra shortly after. -

Sir Colin Davis Discography

1 The Hector Berlioz Website SIR COLIN DAVIS, CH, CBE (25 September 1927 – 14 April 2013) A DISCOGRAPHY Compiled by Malcolm Walker and Brian Godfrey With special thanks to Philip Stuart © Malcolm Walker and Brian Godfrey All rights of reproduction reserved [Issue 10, 9 July 2014] 2 DDDISCOGRAPHY FORMAT Year, month and day / Recording location / Recording company (label) Soloist(s), chorus and orchestra RP: = recording producer; BE: = balance engineer Composer / Work LP: vinyl long-playing 33 rpm disc 45: vinyl 7-inch 45 rpm disc [T] = pre-recorded 7½ ips tape MC = pre-recorded stereo music cassette CD= compact disc SACD = Super Audio Compact Disc VHS = Video Cassette LD = Laser Disc DVD = Digital Versatile Disc IIINTRODUCTION This discography began as a draft for the Classical Division, Philips Records in 1980. At that time the late James Burnett was especially helpful in providing dates for the L’Oiseau-Lyre recordings that he produced. More information was obtained from additional paperwork in association with Richard Alston for his book published to celebrate the conductor’s 70 th birthday in 1997. John Hunt’s most valuable discography devoted to the Staatskapelle Dresden was again helpful. Further updating has been undertaken in addition to the generous assistance of Philip Stuart via his LSO discography which he compiled for the Orchestra’s centenary in 2004 and has kept updated. Inevitably there are a number of missing credits for producers and engineers in the earliest years as these facts no longer survive. Additionally some exact dates have not been tracked down. Contents CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF RECORDING ACTIVITY Page 3 INDEX OF COMPOSERS / WORKS Page 125 INDEX OF SOLOISTS Page 137 Notes 1. -

Danish Cultural Events in New York October 2012

Danish Cultural Events in New York October 2012 - Stay updated! Go to our website: usa.um.dk/ & find us on facebook: facebook.com/consulatedenmarknewyork First Album of the Nielsen Project Hits US Market Danish Dacapo Records and the world famous New York Philharmonic release the first CD of the Nielsen Project – concerts, exhibitions and panel discussion follow. The first recording of The Nielsen Project — a four-year collaboration between New York Philharmonic, Dacapo Records and Naxos America on the Danish composer Carl Nielsen — is now available on the US market. Featuring Music Director Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic’s highly acclaimed performances of Nielsen’s Symphony No. 2, The Four Temperaments, and Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia espansiva, this recording is the first of four that will culminate in a special edition boxed set to be released in the fall of 2015 on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the Danish composer’s birth. This is the first time the New York Philharmonic will record Nielsen’s complete symphonies and concertos, and Danish based Dacapo Records ensures that the recording sessions are based on the highest possible state-of-the-arts technology. “During my years in Sweden, I grew to love Nielsen, and I believe in him as an important composer,” says Maestro Gilbert. “The Nielsen canon deserves to be better known by American audiences: he speaks to everybody. There’s something wonderfully craggy, natural, and forbidding about the sound he creates, but it’s always couched in an Elgar-like, romantic warmth.” Henrik Rørdam, CEO of Dacapo Records, calls the collaboration with the New York Philharmonic around the recordings and concert performances quite exceptional: “It will give a crucial boost to awareness of Carl Nielsen’s music abroad.” Visit our website usa.um.dk & follow us on facebook.com/consulatedenmarknewyork Featured Performance by Danish Star Violinist Nikolaj Znaider Following the first cd release of the Nielsen Project the next live concert recording is right around the corner. -

Carl Nielsen Alan Gilbert

New York Philharmonic Carl Nielsen Alan Gilbert Violin Concerto; Flute Concerto; Clarinet Concerto Nikolaj Znaider; Robert Langevin; Anthony McGill Carl Nielsen (1865–1931) New York Philharmonic Alan Gilbert, Music Director and Conductor Nikolaj Znaider, violin Robert Langevin, flute Anthony McGill, clarinet Concerto for Violin and Orchestra Concerto for Flute and Orchestra Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 33 (1911–12) 35:08 I Prelude: Largo – Allegro cavallerésco ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������18:43 II Poco adagio – ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 6:19 Rondo: Allegretto scherzando ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������10:06 Concerto for Flute and Orchestra (1926)��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������18:16 I Allegro moderato������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������10:55 II Allegretto, un poco���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

LSO/Davis/Noseda at Lincoln Centre, New York

LSO/Davis/Noseda at Lincoln Centre, New York 5 stars Richard Morrison New York’s musical public is famously hard to impress. But three times in five days the audience at Avery Fisher Hall, home of the New York Philharmonic, surged to its feet to give a standing ovation to the London Symphony Orchestra — and in repertoire which, by New York standards, verged on the esoteric: Britten’s War Requiem, Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis and Sibelius. The LSO’s annual residencies at Lincoln Centre are usually well received, particularly if the home team is going through a less-than-glittering era. But this was a triumph, all the more to be savoured because the omens had not seemed auspicious. Two months ago, at the Proms, the LSO’s performance of the Missa Solemnis, also directed by Colin Davis, simply didn’t gell. Here, by contrast, it sounded cogent, unanimous and imbued with a massive spirituality under a conductor who, as he unfolded this epic over nearly two hours, seemed to shed his years and physical frailty and rekindle the old fire. That was infectious. The London Symphony Chorus hurled out those cruel high lines with astounding vigour, as did four fine soloists (with Sarah Connolly outstanding). The Sibelius programme was less grandiose but no less impassioned. Davis has always been capable of assembling the Finn’s diffuse threads with magisterial authority. But here the Second Symphony had something else: an intensity close to anger in the craggy brass outbursts; audacious rubato; and blazing exhilaration from a superbly galvanised orchestra in that hard-won finale.