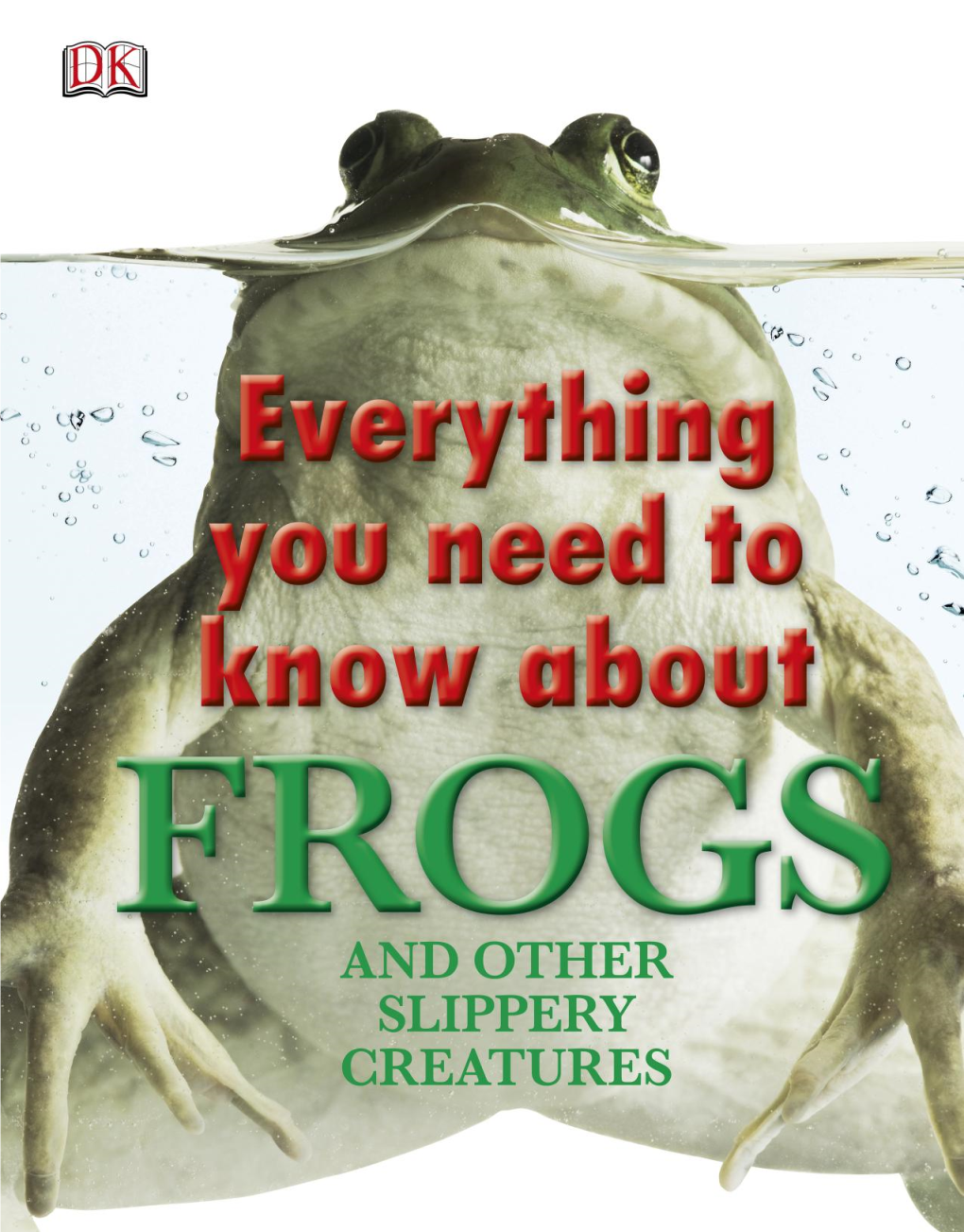

Everything You Need to Know About Frogs and Other Slippery Creatures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pond-Breeding Amphibian Guild

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2015 Pond-breeding Amphibians Guild Primary Species: Flatwoods Salamander Ambystoma cingulatum Carolina Gopher Frog Rana capito capito Broad-Striped Dwarf Siren Pseudobranchus striatus striatus Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum Secondary Species: Upland Chorus Frog Pseudacris feriarum -Coastal Plain only Northern Cricket Frog Acris crepitans -Coastal Plain only Contributors (2005): Stephen Bennett and Kurt A. Buhlmann [SCDNR] Reviewed and Edited (2012): Stephen Bennett (SCDNR), Kurt A. Buhlmann (SREL), and Jeff Camper (Francis Marion University) DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Descriptions This guild contains 4 primary species: the flatwoods salamander, Carolina gopher frog, dwarf siren, and tiger salamander; and 2 secondary species: upland chorus frog and northern cricket frog. Primary species are high priority species that are directly tied to a unifying feature or habitat. Secondary species are priority species that may occur in, or be related to, the unifying feature at some time in their life. The flatwoods salamander—in particular, the frosted flatwoods salamander— and tiger salamander are members of the family Ambystomatidae, the mole salamanders. Both species are large; the tiger salamander is the largest terrestrial salamander in the eastern United States. The Photo by SC DNR flatwoods salamander can reach lengths of 9 to 12 cm (3.5 to 4.7 in.) as an adult. This species is dark, ranging from black to dark brown with silver-white reticulated markings (Conant and Collins 1991; Martof et al. 1980). The tiger salamander can reach lengths of 18 to 20 cm (7.1 to 7.9 in.) as an adult; maximum size is approximately 30 cm (11.8 in.). -

Guidance for Conserving Oregon's Native Turtles Including Best Management Practices

GUIDANCE FOR CONSERVING OREGON’S NATIVE TURTLES INCLUDING BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES the OREGON CONSERVATION STRATEGY the intent of this document is to facilitate better protection and conservation of oregon’s native turtles and their habitats. This document includes recommended Best Management Practices (BMPs) for protecting and conserving Oregon’s two native turtle species, the western painted turtle and the western pond turtle. While there are opportunities for all Oregonians to become more knowledgeable about and participate in turtle conservation efforts, this document is intended primarily for use by natural resource and land managers, land use planners, and project managers. The document has been peer-reviewed and the BMPs are supported by scientifically sound information. The BMPs are intended to be practical and cost-effective so that they can be readily used. Adherence to these BMPs does not necessarily constitute compliance with all applicable federal, state, or local laws. Acknowledgements This document was produced by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) with significant financial and design contributions from The Port of Portland. Input and technical review was provided by the Oregon Native Turtle Working Group which is comprised of representatives from a variety of natural resource agencies, organizations, and institutions. This document arose out of a recommendation from the 2009 Native Turtle Conservation Forum, organized by the Oregon Native Turtle Working Group and hosted by the Oregon Zoo. More information -

Freshwater Fishes

WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE state oF BIODIVERSITY 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction 2 Chapter 2 Methods 17 Chapter 3 Freshwater fishes 18 Chapter 4 Amphibians 36 Chapter 5 Reptiles 55 Chapter 6 Mammals 75 Chapter 7 Avifauna 89 Chapter 8 Flora & Vegetation 112 Chapter 9 Land and Protected Areas 139 Chapter 10 Status of River Health 159 Cover page photographs by Andrew Turner (CapeNature), Roger Bills (SAIAB) & Wicus Leeuwner. ISBN 978-0-620-39289-1 SCIENTIFIC SERVICES 2 Western Cape Province State of Biodiversity 2007 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Andrew Turner [email protected] 1 “We live at a historic moment, a time in which the world’s biological diversity is being rapidly destroyed. The present geological period has more species than any other, yet the current rate of extinction of species is greater now than at any time in the past. Ecosystems and communities are being degraded and destroyed, and species are being driven to extinction. The species that persist are losing genetic variation as the number of individuals in populations shrinks, unique populations and subspecies are destroyed, and remaining populations become increasingly isolated from one another. The cause of this loss of biological diversity at all levels is the range of human activity that alters and destroys natural habitats to suit human needs.” (Primack, 2002). CapeNature launched its State of Biodiversity Programme (SoBP) to assess and monitor the state of biodiversity in the Western Cape in 1999. This programme delivered its first report in 2002 and these reports are updated every five years. The current report (2007) reports on the changes to the state of vertebrate biodiversity and land under conservation usage. -

Catalogue of the Amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and Annotated Species List, Distribution, and Conservation 1,2César L

Mannophryne vulcano, Male carrying tadpoles. El Ávila (Parque Nacional Guairarepano), Distrito Federal. Photo: Jose Vieira. We want to dedicate this work to some outstanding individuals who encouraged us, directly or indirectly, and are no longer with us. They were colleagues and close friends, and their friendship will remain for years to come. César Molina Rodríguez (1960–2015) Erik Arrieta Márquez (1978–2008) Jose Ayarzagüena Sanz (1952–2011) Saúl Gutiérrez Eljuri (1960–2012) Juan Rivero (1923–2014) Luis Scott (1948–2011) Marco Natera Mumaw (1972–2010) Official journal website: Amphibian & Reptile Conservation amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 13(1) [Special Section]: 1–198 (e180). Catalogue of the amphibians of Venezuela: Illustrated and annotated species list, distribution, and conservation 1,2César L. Barrio-Amorós, 3,4Fernando J. M. Rojas-Runjaic, and 5J. Celsa Señaris 1Fundación AndígenA, Apartado Postal 210, Mérida, VENEZUELA 2Current address: Doc Frog Expeditions, Uvita de Osa, COSTA RICA 3Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales, Museo de Historia Natural La Salle, Apartado Postal 1930, Caracas 1010-A, VENEZUELA 4Current address: Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Río Grande do Sul (PUCRS), Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Av. Ipiranga 6681, Porto Alegre, RS 90619–900, BRAZIL 5Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas, Altos de Pipe, apartado 20632, Caracas 1020, VENEZUELA Abstract.—Presented is an annotated checklist of the amphibians of Venezuela, current as of December 2018. The last comprehensive list (Barrio-Amorós 2009c) included a total of 333 species, while the current catalogue lists 387 species (370 anurans, 10 caecilians, and seven salamanders), including 28 species not yet described or properly identified. Fifty species and four genera are added to the previous list, 25 species are deleted, and 47 experienced nomenclatural changes. -

Breviceps Adspersus” Documents B

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 397-406 (2021) (published online on 22 February 2021) Phylogenetic analysis of “Breviceps adspersus” documents B. passmorei Minter et al., 2017 in Limpopo Province, South Africa Matthew P. Heinicke1,*, Mohamad H. Beidoun1, Stuart V. Nielsen1,2, and Aaron M. Bauer3 Abstract. Recent systematic work has shown the Breviceps mossambicus species group to be more species-rich than previously documented and has brought into question the identity of many populations, especially in northeastern South Africa. We obtained genetic data for eight specimens originally identified as B. adspersus from Limpopo Province, South Africa, as well as numerous specimens from the core range of B. adspersus in Namibia and Zimbabwe. Phylogenetic analysis shows that there is little genetic variation across the range of B. adspersus. However, most of our Limpopo specimens are not B. adspersus but rather B. passmorei, a species previously known only from the immediate vicinity of its type locality in KwaZulu-Natal. These new records extend the known range of B. passmorei by 360 km to the north. Our results emphasize the need to obtain fine- scale range-wide genetic data for Breviceps to better delimit the diversity and biogeography of the genus. Keywords. Brevicipitidae, cryptic species, Microhylidae, rain frog, systematics, Transvaal Introduction Breviceps adspersus, with a lectotype locality listed as “Damaraland” [= north-central Namibia], and other The genus Breviceps Merrem, 1820 includes 18 or 19 syntypes from both Damaraland and “Transvaal” [= described species of rain frogs distributed across eastern northeastern South Africa], has a southern distribution, and southern Africa (AmphibiaWeb, 2020; Frost, 2020). ranging from Namibia across much of Botswana, The genus includes two major clades: the gibbosus Zimbabwe, and South Africa to western Mozambique. -

Wood Frog (Rana Sylvatica): a Technical Conservation Assessment

Wood Frog (Rana sylvatica): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project March 24, 2005 Erin Muths1, Suzanne Rittmann1, Jason Irwin2, Doug Keinath3, Rick Scherer4 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Fort Collins Science Center, 2150 Centre Ave. Bldg C, Fort Collins, CO 80526 2 Department of Biology, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA 17837 3 Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming, P.O. Box 3381, Laramie, WY 82072 4 Colorado State University, GDPE, Fort Collins, CO 80524 Peer Review Administered by Society for Conservation Biology Muths, E., S. Rittman, J. Irwin, D. Keinath, and R. Scherer. (2005, March 24). Wood Frog (Rana sylvatica): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/woodfrog.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the help of the many people who contributed time and answered questions during our review of the literature. AUTHORS’ BIOGRAPHIES Dr. Erin Muths is a Zoologist with the U.S. Geological Survey – Fort Collins Science Center. She has been studying amphibians in Colorado and the Rocky Mountain Region for the last 10 years. Her research focuses on demographics of boreal toads, wood frogs and chorus frogs and methods research. She is a principle investigator for the USDOI Amphibian Research and Monitoring Initiative and is an Associate Editor for the Northwestern Naturalist. Dr. Muths earned a B.S. in Wildlife Ecology from the University of Wisconsin, Madison (1986); a M.S. in Biology (Systematics and Ecology) from Kansas State University (1990) and a Ph.D. -

Bell MSC 2009.Pdf (8.762Mb)

THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE DESERT RAIN FROG (Breviceps macrops) IN SOUTH AFRICA Kirsty Jane Bell A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magister Scientiae in the Department of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, University of the Western Cape Supervisor: Dr. Alan Channing April 2009 ii THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE DESERT RAIN FROG (Breviceps macrops) IN SOUTH AFRICA Kirsty Jane Bell Keywords: Desert Rain Frog Breviceps macrops Distribution Southern Africa Diamond Coast Environmental influences Genetics Conservation status Anthropogenic disturbances Current threats iii ABSTRACT The Distribution of the Desert Rain Frog (Breviceps macrops) in South Africa Kirsty Jane Bell M.Sc. Thesis, Department of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, University of the Western Cape. The desert rain frog (Breviceps macrops) is an arid adapted anuran found on the west coast of southern Africa occurring within the Sandveld of the Succulent Karoo Biome. It is associated with white aeolian sand deposits, sparse desert vegetation and coastal fog. Little is known of its behaviour and life history strategy. Its distribution is recognised in the Atlas and Red Data Book of the Frogs of South Africa, Lesotho, and Swaziland as stretching from Koiingnaas in the South to Lüderitz in the North and 10 km inland. This distribution has been called into question due to misidentification and ambiguous historical records. This study examines the distribution of B. macrops in order to clarify these discrepancies, and found that its distribution does not stretch beyond 2 km south of the town of Kleinzee nor further than 6 km inland throughout its range in South Africa. -

The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 44 (2007)

THE BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PapYROLOGIsts Volume 44 2007 ISSN 0003-1186 The current editorial address for the Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists is: Peter van Minnen Department of Classics University of Cincinnati 410 Blegen Library Cincinnati, OH 45221-0226 USA [email protected] The editors invite submissions not only fromN orth-American and other members of the Society but also from non-members throughout the world; contributions may be written in English, French, German, or Italian. Manu- scripts submitted for publication should be sent to the editor at the address above. Submissions can be sent as an e-mail attachment (.doc and .pdf) with little or no formatting. A double-spaced paper version should also be sent to make sure “we see what you see.” We also ask contributors to provide a brief abstract of their article for inclusion in L’ Année philologique, and to secure permission for any illustration they submit for publication. The editors ask contributors to observe the following guidelines: • Abbreviations for editions of papyri, ostraca, and tablets should follow the Checklist of Editions of Greek, Latin, Demotic and Coptic Papyri, Ostraca and Tablets (http://scriptorium.lib.duke.edu/papyrus/texts/clist.html). The volume number of the edition should be included in Arabic numerals: e.g., P.Oxy. 41.2943.1-3; 2968.5; P.Lond. 2.293.9-10 (p.187). • Other abbreviations should follow those of the American Journal of Ar- chaeology and the Transactions of the American Philological Association. • For ancient and Byzantine authors, contributors should consult the third edition of the Oxford Classical Dictionary, xxix-liv, and A Patristic Greek Lexi- con, xi-xiv. -

Misgund Orchards

MISGUND ORCHARDS ENVIRONMENTAL AUDIT 2014 Grey Rhebok Pelea capreolus Prepared for Mr Wayne Baldie By Language of the Wilderness Foundation Trust In March 2002 a baseline environmental audit was completed by Conservation Management Services. This foundational document has served its purpose. The two (2) recommendations have been addressed namely; a ‘black wattle control plan’ in conjunction with Working for Water Alien Eradication Programme and a survey of the fish within the rivers was also addressed. Furthermore updated species lists have resulted (based on observations and studies undertaken within the region). The results of these efforts have highlighted the significance of the farm Misgund Orchards and the surrounds, within the context of very special and important biodiversity. Misgund Orchards prides itself with a long history of fruit farming excellence, and has strived to ensure a healthy balance between agricultural priorities and our environment. Misgund Orchards recognises the need for a more holistic and co-operative regional approach towards our environment and needs to adapt and design a more sustainable approach. The context of Misgund Orchards is significant, straddling the protected areas Formosa Forest Reserve (Niekerksberg) and the Baviaanskloof Mega Reserve. A formidable mountain wilderness with World Heritage Status and a Global Biodiversity Hotspot (See Map 1 overleaf). Rhombic egg eater Dasypeltis scabra MISGUND ORCHARDS Langkloof Catchment MAP 1 The regional context of Misgund Orchards becomes very apparent, where the obvious strategic opportunity exists towards creating a bridge of corridors linking the two mountain ranges Tsitsikamma and Kouga (south to north). The environmental significance of this cannot be overstated – essentially creating a protected area from the ocean into the desert of the Klein-karoo, a traverse of 8 biomes, a veritable ‘garden of Eden’. -

Amphibiaweb's Illustrated Amphibians of the Earth

AmphibiaWeb's Illustrated Amphibians of the Earth Created and Illustrated by the 2020-2021 AmphibiaWeb URAP Team: Alice Drozd, Arjun Mehta, Ash Reining, Kira Wiesinger, and Ann T. Chang This introduction to amphibians was written by University of California, Berkeley AmphibiaWeb Undergraduate Research Apprentices for people who love amphibians. Thank you to the many AmphibiaWeb apprentices over the last 21 years for their efforts. Edited by members of the AmphibiaWeb Steering Committee CC BY-NC-SA 2 Dedicated in loving memory of David B. Wake Founding Director of AmphibiaWeb (8 June 1936 - 29 April 2021) Dave Wake was a dedicated amphibian biologist who mentored and educated countless people. With the launch of AmphibiaWeb in 2000, Dave sought to bring the conservation science and basic fact-based biology of all amphibians to a single place where everyone could access the information freely. Until his last day, David remained a tirelessly dedicated scientist and ally of the amphibians of the world. 3 Table of Contents What are Amphibians? Their Characteristics ...................................................................................... 7 Orders of Amphibians.................................................................................... 7 Where are Amphibians? Where are Amphibians? ............................................................................... 9 What are Bioregions? ..................................................................................10 Conservation of Amphibians Why Save Amphibians? ............................................................................. -

Tcu-Smu Series

FROG HISTORY 2008 TCU FOOTBALL TCU FOOTBALL THROUGH THE AGES 4General TCU is ready to embark upon its 112th year of Horned Frog football. Through all the years, with the ex cep tion of 1900, Purple ballclubs have com pet ed on an or ga nized basis. Even during the war years, as well as through the Great Depres sion, each fall Horned Frog football squads have done bat tle on the gridiron each fall. 4BEGINNINGS The newfangled game of foot ball, created in the East, made a quiet and un offcial ap pear ance on the TCU campus (AddRan College as it was then known and lo cat ed in Waco, Tex as, or nearby Thorp Spring) in the fall of 1896. It was then that sev er al of the col lege’s more ro bust stu dents, along with the en thu si as tic sup port of a cou ple of young “profs,” Addison Clark, Jr., and A.C. Easley, band ed to gether to form a team. Three games were ac tu al ly played that season ... all af ter Thanks giv ing. The first con test was an 86 vic to ry over Toby’s Busi ness College of Waco and the other two games were with the Houston Heavy weights, a town team. By 1897 the new sport had progressed and AddRan enlisted its first coach, Joe J. Field, to direct the team. Field’s ballclub won three games that autumn, including a first victory over Texas A&M. The only loss was to the Univer si ty of Tex as, 1810. -

Trade in Live Reptiles, Its Impact on Wild Populations, and the Role of the European Market

BIOC-06813; No of Pages 17 Biological Conservation xxx (2016) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bioc Review Trade in live reptiles, its impact on wild populations, and the role of the European market Mark Auliya a,⁎,SandraAltherrb, Daniel Ariano-Sanchez c, Ernst H. Baard d,CarlBrownd,RafeM.Browne, Juan-Carlos Cantu f,GabrieleGentileg, Paul Gildenhuys d, Evert Henningheim h, Jürgen Hintzmann i, Kahoru Kanari j, Milivoje Krvavac k, Marieke Lettink l, Jörg Lippert m, Luca Luiselli n,o, Göran Nilson p, Truong Quang Nguyen q, Vincent Nijman r, James F. Parham s, Stesha A. Pasachnik t,MiguelPedronou, Anna Rauhaus v,DannyRuedaCórdovaw, Maria-Elena Sanchez x,UlrichScheppy, Mona van Schingen z,v, Norbert Schneeweiss aa, Gabriel H. Segniagbeto ab, Ruchira Somaweera ac, Emerson Y. Sy ad,OguzTürkozanae, Sabine Vinke af, Thomas Vinke af,RajuVyasag, Stuart Williamson ah,1,ThomasZieglerai,aj a Department Conservation Biology, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Conservation (UFZ), Permoserstrasse 15, 04318 Leipzig, Germany b Pro Wildlife, Kidlerstrasse 2, 81371 Munich, Germany c Departamento de Biología, Universidad del Valle de, Guatemala d Western Cape Nature Conservation Board, South Africa e Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology,University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute, 1345 Jayhawk Blvd, Lawrence, KS 66045, USA f Bosques de Cerezos 112, C.P. 11700 México D.F., Mexico g Dipartimento di Biologia, Universitá Tor Vergata, Roma, Italy h Amsterdam, The Netherlands