© Copyright by Brett Thomas Olmsted May 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseline Environmental Assessment

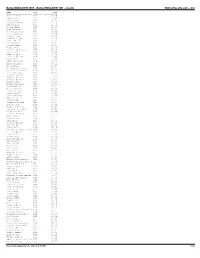

www.aktpeerless.com www.aktpeerless.com Lead 1,850,000 ug/Kg (1,3) Chromium, Total 93,600 ug/Kg (1,2) Lead 1,050,000 ug/Kg (1,3) Mercury, Total 511 ug/Kg (2) www.aktpeerless.com Lead 6 ug/L (1) www.aktpeerless.com Table 1: Summary of Soil Analytical Data 1101 Chavez Avenue Flint, Michigan AKT Peerless Project No. -

RACER BC 2016 Yearly Trend Report 2017 05.12.Docx 1/5 Ms

Ms. Mary Vanderlaan Arcadis of Michigan, LLC Supervisor, Lansing District 300 Metro Center Boulevard Michigan Department of Environmental Quality Suite 250 Water Resources Division Warwick 525 W. Allegan (Constitution Hall, 4N) Rhode Island 02886 P. O. Box 30242 Tel 401 738 3887 Fax 401 732 1686 Lansing, MI 48909-7742 www.arcadis.com ENVIRONMENT Subject: NPDES Permit No. MI0001597 – 2016 Yearly Stormwater Trend Monitoring Data Date: RACER – Buick City Site May 12, 2017 Flint, Michigan Contact: Christopher S. Peters Dear Ms. Vanderlaan: Phone: This report was prepared by Arcadis on behalf of the Revitalizing Auto 517.324.5052 Communities Environmental Response (RACER) Trust, for the Buick City Site (formerly known as the GM - Powertrain Flint North). The Buick City Site (Site) is Email: located near 902 East Leith Street in Flint, Michigan, in Genesee County and [email protected] encompasses approximately 400 acres of land as shown on Figure 1. The portion of the Site located north of Leith Street (hereafter referred to as the Our ref: B0064410.2017 Northend) was in part occupied by General Motors LLC (GM LLC) for manufacturing operations until December 6, 2010. Since December 6, 2010 there have been no manufacturing operations at the Site. Demolition of the Northend of the Site was completed in April 2012. Building demolition was completed in 2001 in the portion of the property located south of Leith Street, which is referred to as the Southend. RACER is submitting annual stormwater monitoring data as required by Section 1.A.7.a.1 of the above referenced National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit for the Site. -

The BG News April 14, 1981

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-14-1981 The BG News April 14, 1981 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 14, 1981" (1981). BG News (Student Newspaper). 3856. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/3856 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Tuesday. -\ Home or work, Opening day Falcons on the women want marks right track respect Indian summer Page 2 Page 5 Page 8 Vary cloudy. High April 14, 1981 50-55 F, low upper 20s F. 90 percent chine* of The B G News precipitation. Bowling Green State University SGA candidates run unopposed as election nears by Kyla Silvan "I didn't think that gave the students much of Margie Potapchuk is running unopposed for tailed checking the candidates' grade point SHE SATO she does not like the idea of write- News ataff raportar a choice." one of the two Founders openings, and averages to ensure that they are carrying the in candidates. Johnson said he is pleased his position is op- Firelands has not submitted a candidate. required 2.0 GPA and a random survey of the "I am a little bit fearful of that," she said, Student Government Association candidates posed. -

Cleanup Progresses at Former Factory Complex

Cleanup Progresses at Former Factory Complex Buick City Site Revitalizing Auto Communities Flint, Michigan November 2018 Environmental Response Trust The former General Motors-Buick City manufacturing complex is For more information undergoing environmental cleanup that will take several years to complete. If you need more information, have Buick City includes approximately 413 acres divided into the Northend questions or would like to be added (north of Leith Street) and the Southend (south of Leith Street) – see to the mailing list about the Buick attached Site Map. Revitalizing Auto Communities Environmental City site, please contact one of these Response (RACER) Trust is tasked with conducting the cleanup and individuals: marketing the property for sale and redevelopment. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) authorizes and oversees the Christopher Black required cleanup work with the support of the Michigan Department of EPA Project Manager Environmental Quality (DEQ). RCRA Corrective Action Section 2 312-886-1451 Two parcels (one on the Northend and one on the Southend), totaling [email protected] approximately 49 acres, have been sold and successfully redeveloped for EPA toll-free: 800-621-8431 new manufacturing operations. About 364 acres are still owned by EPA Region 5 RACER Trust and are available for purchase and redevelopment. RACER 77 W. Jackson Blvd. Trust continues to work on completion of the necessary environmental Chicago, IL 60604-3590 cleanup work for the entire 413-acre site. Environmental cleanup that is necessary because of GM’s historical operations remains RACER Trust’s Kevin Lund, PE responsibility, regardless of who owns the property. MDEQ Project Coordinator Redevelopment Support Site Conditions 517-513-1846 Buick City contains soil and groundwater (water below the surface) that is [email protected] contaminated with various petroleum products and chemicals that were Jackson District Office used as part of GM’s car and truck manufacturing. -

Forwar Into the Breach

Forward! Into the Breach A Compendium Workbook to Into the Breach An Apostolic Exhortation to Catholic Men, My Spiritual Sons in the Diocese of Phoenix By Bishop Thomas J. Olmsted Anthony J. Castellano To my five sons, Christopher, Joseph (†2019), Stephen, Paul, and Michael; my son in-law, Matthew; my three grandsons, Luke, Leo, and Eli; and to my father, Carmine Christopher Castellano June 8, 2019 FORWARD! INTO THE BREACH: A Compendium Workbook to Into the Breach, An Apostolic Exhortation to Men, by Bishop Thomas J. Olmsted ©2016 by Anthony J. Castellano. All rights reserved. For more information, see “www.ForwardIntoTheBreach.com”. Into the Breach is an Apostolic Exhortation from His Excellency +Thomas J. Olmsted, Bishop of Phoenix, promulgated on September 29, 2015, copyright © 2015 by Most Rev. Thomas J. Olmsted, Bishop of the Roman Catholic Church of the Diocese of Phoenix. Excerpts used with permission. All rights reserved. For more information, see “www.IntoTheBreach.net”. Except where noted, Scripture quotations are from the Catholic Edition of the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1965, 1966 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (NIV) are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.zondervan.com The “NIV” and “New International Version” are trademarks registered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by Biblica, Inc.™ Scripture quotations marked (ESV) are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. -

The National Catholic Weekly Oct. 31, 2011 $3.50 of Many Things

THE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WEEKLY OCT. 31, 2011 $3.50 OF MANY THINGS PUBLISHED BY JESUITS OF THE UNITED STATES alloween was not always fun. But Halloween is not just a game for To the ancient Celts, who children. We know from the specialty EDITOR IN CHIEF seem to have originated it, Halloween stores that suddenly open Drew Christiansen, S.J. Halloween was deadly serious. By for the season that Halloween is big EDITORIAL DEPARTMENT October’s end, the dark came early, the business. As Dublin came alive at MANAGING EDITOR cold never left and death dwelt nearby. October’s end last year, phantoms of Robert C. Collins, S.J. Surviving the coming winter demanded every sort haunted O’Connell Street EDITORIAL DIRECTOR attention. and the Temple Bar—not so many Karen Sue Smith These peoples of ancient Ireland ghosts and demons as St. Patricks and ONLINE EDITOR knew of thin places—sacred wells, nuns and punks, all with healthy Maurice Timothy Reidy haunted groves—where the veil between draughts of Guinness. They would CULTURE EDITOR our world of stone and wood and anoth - hardly scare away the forces of evil, but James Martin, S.J. er world of spirit and imagination was they were having a lot of fun. LITERARY EDITOR flimsy. And at Halloween, they felt, these We have other ways to confront our Patricia A. Kossmann worlds were very close indeed. So they fears today, our demons, our ghosts, our POETRY EDITOR dressed up to confront and confuse the hostile powers. There are things that James S. Torrens, S.J. -

Bolderboulder 2005 - Bolderboulder 10K - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

BolderBOULDER 2005 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Michael Aish M28 30:29 Jesus Solis M21 30:45 Nelson Laux M26 30:58 Kristian Agnew M32 31:10 Art Seimers M32 31:51 Joshua Glaab M22 31:56 Paul DiGrappa M24 32:14 Aaron Carrizales M27 32:23 Greg Augspurger M27 32:26 Colby Wissel M20 32:36 Luke Garringer M22 32:39 John McGuire M18 32:42 Kris Gemmell M27 32:44 Jason Robbie M28 32:47 Jordan Jones M23 32:51 Carl David Kinney M23 32:51 Scott Goff M28 32:55 Adam Bergquist M26 32:59 trent r morrell M35 33:02 Peter Vail M30 33:06 JOHN HONERKAMP M29 33:10 Bucky Schafer M23 33:12 Jason Hill M26 33:15 Avi Bershof Kramer M23 33:17 Seth James DeMoor M19 33:20 Tate Behning M23 33:22 Brandon Jessop M26 33:23 Gregory Winter M26 33:25 Chester G Kurtz M30 33:27 Aaron Clark M18 33:28 Kevin Gallagher M25 33:30 Dan Ferguson M23 33:34 James Johnson M36 33:38 Drew Tonniges M21 33:41 Peter Remien M25 33:45 Lance Denning M43 33:48 Matt Hill M24 33:51 Jason Holt M18 33:54 David Liebowitz M28 33:57 John Peeters M26 34:01 Humberto Zelaya M30 34:05 Craig A. Greenslit M35 34:08 Galen Burrell M25 34:09 Darren De Reuck M40 34:11 Grant Scott M22 34:12 Mike Callor M26 34:14 Ryan Price M27 34:15 Cameron Widoff M35 34:16 John Tribbia M23 34:18 Rob Gilbert M39 34:19 Matthew Douglas Kascak M24 34:21 J.D. -

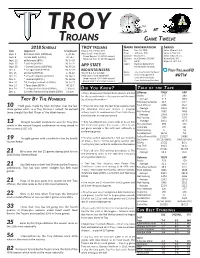

Trojans Game Twelve 2018 Schedule TROY TROJANS Game Information Series Date Opponent Time/Result Record: 9-2, 7-0 Sun Belt Date: Nov

TROY AT TroJANS GAME TWELVE 2018 SCHEDULE TROY TROJANS Game Information Series Date Opponent Time/Result Record: 9-2, 7-0 Sun Belt Date: Nov. 24, 2018 Series (Overall): 3-3 Sept. 1 #22 Boise State (ESPNews) L, 20-56 Head Coach: Neal Brown Time: 1:35 p.m. (CT) Series in Troy: 2-2 Location: Boone, N.C. Series in Boone: 1-1 Sept. 8 Florida A&M (ESPN+) W, 59-7 Career Record: 34-15 (4th season) Record at Troy: 34-15 (4th season) Stadium: Kidd-Brewer (30,000) Neutral Site: 0-0 Sept. 15 at Nebraska (BTN) W, 24-19 TV: ESPN+ Brown vs. APP: 1-1 Sept. 22 * at ULM (ESPN+) W, 35-27 Talent: Harrison Battle (PxP) Sept. 29 * Coastal Carolina (ESPN3) W, 45-21 APP STATE Pierre Banks (Analyst) Oct. 4 * Georgia State (ESPNU) W, 37-20 MOUNTAINEERS TROYTROJANSFB Oct. 13 at Liberty (ESPN3) L, 16-22 Record: 8-2, 6-1 Sun Belt Radio: Troy Sports Radio Network Oct. 23 * at South Alabama (ESPN2) W, 38-17 Head Coach: Scott Satterfield Talent: Barry McKnight (PxP) #RTW Career Record: 49-24 (6th season) Jerry Miller (Analyst) Nov. 3 * Louisiana (ESPN+) W, 26-16 Chris Blackshear (Sideline) Nov. 10 *at Georgia Southern (ESPN+) W, 35-21 Record at APP: 49-24 (6th season) Nov. 17 * Texas State (ESPN+) W, 12-7 Nov. 24 * at Appalachian State (ESPN+) 1:30 p.m. D ID Y OU K N OW ? T ALE O F T HE T APE Dec. 1 Sun Belt Championship Game (ESPN) 11 a.m. -

SW Kansans Make Their Voices Heard at Topeka Rally

The Southwest Kansas Register BISHOP JOHN B. BRUNGARDT February 13, 2011 Page 25 SW Kansans make their voices heard at Topeka rally John Hough/SKR Photos Above: Father Wesley Schawe, far right, stands on the steps of the capitol build- ing with the youth and adults from the Diocese of Dodge City at the pro-life March for Peace rally Jan. 24 in Topeka. Top, right: Bishop-elect John B. Brun- gardt stands with youth from the Diocese of Dodge City. At right: Bishop-elect Brungardt celebrates Mass with Abbot Gregory Polan, O.S.B., at the Topeka Expo Center. Chris Riggs/ Advance Photo Page 26 February 13, 2011 BISHOP JOHN B. BRUNGARDT The Southwest Kansas Register The Coat of Arms of the Most Rev. John Brungardt (Continued from Page 22) the sun in heraldic shape, with a round On either side of the vertical the pro-life movement, as we are called to The vertical bar dividing this section disc surrounded by 16 rays, alternating respect the dignity of the human person, refers to the 100th meridian which runs wavy and straight, on a blue field. This bar are two Indian arrow- from conception to natural death, as we through Dodge City. The bar is again “Sun in Splendor” or “In His Glory” is a heads. They represent the are all made in God’s divine image and divided to indicate that the division of Messianic symbol of our Lord. The sun likeness. The rose rests on an argent (sil- Central and Mountain Time zones which symbolizes the light of God, who lights Native American heritage of ver) field, symbolic of transparency, then also runs through the diocese. -

June 2011 Newsletter

‘j4~ CATHOLIC DIOCESE OF LANSING WWW DIOCESEOF AN NO ORG Courage & EnCourage -~s 2 - 228 North Walnut Street Lansing, Michigan 48933-1122 517-342-2596 t Facsimile: 517.342.2468 [email protected] ENCOURAGE SUPPORT GROUP MEETING Roman Catholic Diocese of Lansing Chapter When: Sunday June 26, 2011 from 2:30 to 4:00pm Where: Holy Spirit Catholic Church 9565 Musch Rd. Brighton, Michigan 48116 Directions: US-23 to Silver Lake Rd. Exit (exit #55) West on Silver Lake Rd. to Whitmore Lake Rd. (a short distance). South on Whitmore Lake Rd. to Winans Lake Rd.(a three way stop). West on Winans Lake Rd. approximately one mile to entrance marked with a sign for Holy Spirit Cemetery and Holy Spirit Rectory and School. Turn left. We meet in portable classroom number four. Look for Encourage Meeting signs. “Come Holy Spirit, fill the hearts of your faithful. Send forth your Spirit and renew the face of the earth.” May you have a blessed and Holy Spirit filled Pentecost. Please note that although you are receiving the letter at the usual time the meeting itself is a week later. We moved the June meeting to the fourth Sunday (the to accommodate family gatherings on Father’s Day. We have enclosed two important communications from Fr. Paul Check, the Director of Courage, regarding events and news from the international Courage office in Norwalk, CT. We would urge you to prayerfully consider attending the annual conference. The conference is more than simply an information gathering experience. It is a life changing event. Those who attend will pray, celebrate liturgy, and form relationships that will bless them for years to come. -

Brown and Gold," We Have Steadily Contributed to Its Columns

m% M '#% #j €T**f^ Foreword HE task was there, the incentive, too—that we continue the work of our predecessors—but the means was the stumbling Mock. The task looked large, the prospects .lark. The Year Hook is something new in the College literary enterprises, this being but the second number that has appeared. The difficulties were apparent, but our willingness was unlimited, our ambi- tion ever determined that it should he worthy of the College of the Sacred Heart. We endeavored. How well we succeeded is for you to judge. With this College we hid you make better acquaintance through the result of the efforts we have put forth to make this work representative of its ideals and achievements and last, but not least, its students and their activities. To the majority this is but a new view of old matter: to many it brings recol- lections of former days: to the remainder, we hope, it furnishes interest and enjoyment, and to all it is the portal of a better knowledge of our institution ami members. May this glimpse of the past, detail of the present, and hint of the future, merit your appreciation in proportion to that welcome we feel von so generously extend it. A. M. D. G. DEDICATION With Cherished Affection We dedicate this Year Book to Our Honored President and Sincerest Adviser In token of our Gratitude and Esteem. June, 1920. Reverend John J. Brown, S.J. President Page Fi\ FACULTY REUGtONI ET B0NI5ARTIBUS V REV. JOHN M. FLOYD, S..T. REV. FRANCIS X. -

GAO-11-471 TARP: Treasury's Exit from GM and Chrysler Highlights

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Committees GAO May 2011 TARP Treasury’s Exit from GM and Chrysler Highlights Competing Goals, and Results of Support to Auto Communities Are Unclear GAO-11-471 May 2011 TARP Accountability • Integrity • Reliability Treasury’s Exit from GM and Chrysler Highlights Its Competing Goals, and Results of Support to Auto Communities Are Unclear Highlights of GAO-11-471, a report to congressional committees Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found Since December 2008, the Substantial federal assistance allowed GM and Chrysler to restructure their Department of the Treasury costs and improve their financial condition. Through federally-funded (Treasury) has committed $62 billion restructuring, GM and Chrysler reported lowering production costs and in Troubled Asset Relief Program capacities by closing or idling factories, laying off employees, and reducing (TARP) funding to General Motors their debt and number of vehicle brands and models. These changes enabled (GM) and Chrysler. Under GAO’s both companies to report operating profits and reduce costs enough to be mandate to oversee TARP, this report profitable at much lower sales levels than ever before. Nevertheless, to remain addresses (1) how restructuring with profitable, both companies must manage challenges affecting both their costs, federal assistance has affected GM’s including debt levels, and vehicle demand, such as launching products that are and Chrysler’s financial condition, attractive to consumers amid rising fuel prices. (2) what Treasury has done to ensure that it disinvests in GM and Chrysler Treasury has recouped roughly 40 percent of its investments in GM and so as to protect taxpayers’ interests Chrysler, but the extent to which it will further recoup its investments and what risks remain in recouping depends on how it balances two potentially competing goals for divestment— its investments, and (3) how to maximize taxpayers’ return and to exit the companies as soon as restructuring has affected auto practicable.