Introduction to Volume 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tour Report 1 – 8 January 2016

The Gambia - In Style! Naturetrek Tour Report 1 – 8 January 2016 White-throated Bee-eaters Violet Turaco by Kim Taylor African Wattled Lapwing Blue-bellied Roller Report compiled by Marcus John Images courtesy of Kim Taylor & Marcus John Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk The Gambia - In Style! Tour Report Tour Participants: Marcus John (leaders) with six Naturetrek clients Summary The Gambia is an ideal destination for a relaxed holiday and offers a great introduction to the diverse and colourful birdlife of Africa. We spent the week at the stunning Mandina Lodges, a unique place that lies on a secluded mangrove-lined tributary of the mighty River Gambia. The lodges are situated next to the creek and within the Makasuto Forest, which comprises over a thousand acres of pristine, protected forest. Daily walks took us out through the woodland and into the rice fields and farmland beyond, where a great range of birds and butterflies can be found. It was sometimes hard to know where to look as parrots, turacos, rollers and bee-eaters all vied for our attention! Guinea Baboons are resident in the forest and were very approachable; Green Vervet Monkeys were seen nearly every day and we also found a group of long-limbed Patas Monkeys, the fastest primates in the world! Boat trips along the creek revealed a diverse selection of waders, kingfishers and other waterbirds; fourteen species of raptor were also seen during the week. -

Borneo: Broadbills & Bristleheads

TROPICAL BIRDING Trip Report: BORNEO June-July 2012 A Tropical Birding Set Departure Tour BORNEO: BROADBILLS & BRISTLEHEADS RHINOCEROS HORNBILL: The big winner of the BIRD OF THE TRIP; with views like this, it’s easy to understand why! 24 June – 9 July 2012 Tour Leader: Sam Woods All but one photo (of the Black-and-yellow Broadbill) were taken by Sam Woods (see http://www.pbase.com/samwoods or his blog, LOST in BIRDING http://www.samwoodsbirding.blogspot.com for more of Sam’s photos) 1 www.tropicalbirding.com Tel: +1-409-515-0514 E-mail: [email protected] TROPICAL BIRDING Trip Report: BORNEO June-July 2012 INTRODUCTION Whichever way you look at it, this year’s tour of Borneo was a resounding success: 297 bird species were recorded, including 45 endemics . We saw all but a few of the endemic birds we were seeking (and the ones missed are mostly rarely seen), and had good weather throughout, with little rain hampering proceedings for any significant length of time. Among the avian highlights were five pitta species seen, with the Blue-banded, Blue-headed, and Black-and-crimson Pittas in particular putting on fantastic shows for all birders present. The Blue-banded was so spectacular it was an obvious shoe-in for one of the top trip birds of the tour from the moment we walked away. Amazingly, despite absolutely stunning views of a male Blue-headed Pitta showing his shimmering cerulean blue cap and deep purple underside to spectacular effect, he never even got a mention in the final highlights of the tour, which completely baffled me; he simply could not have been seen better, and birds simply cannot look any better! However, to mention only the endemics is to miss the mark, as some of the, other, less local birds create as much of a stir, and can bring with them as much fanfare. -

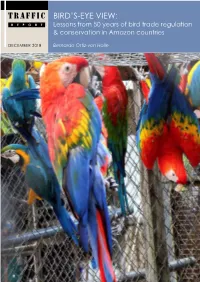

TRAFFIC Bird’S-Eye View: REPORT Lessons from 50 Years of Bird Trade Regulation & Conservation in Amazon Countries

TRAFFIC Bird’s-eye view: REPORT Lessons from 50 years of bird trade regulation & conservation in Amazon countries DECEMBER 2018 Bernardo Ortiz-von Halle About the author and this study: Bernardo Ortiz-von Halle, a biologist and TRAFFIC REPORT zoologist from the Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, has more than 30 years of experience in numerous aspects of conservation and its links to development. His decades of work for IUCN - International Union for Conservation of Nature and TRAFFIC TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade monitoring in South America have allowed him to network, is a leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade acquire a unique outlook on the mechanisms, in wild animals and plants in the context institutions, stakeholders and challenges facing of both biodiversity conservation and the conservation and sustainable use of species sustainable development. and ecosystems. Developing a critical perspective The views of the authors expressed in this of what works and what doesn’t to achieve lasting conservation goals, publication do not necessarily reflect those Bernardo has put this expertise within an historic framework to interpret of TRAFFIC, WWF, or IUCN. the outcomes of different wildlife policies and actions in South America, Reproduction of material appearing in offering guidance towards solutions that require new ways of looking at this report requires written permission wildlife trade-related problems. Always framing analysis and interpretation from the publisher. in the midst of the socioeconomic and political frameworks of each South The designations of geographical entities in American country and in the region as a whole, this work puts forward this publication, and the presentation of the conclusions and possible solutions to bird trade-related issues that are material, do not imply the expression of any linked to global dynamics, especially those related to wildlife trade. -

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

Birds of Chile a Photo Guide

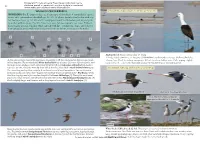

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be 88 distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical 89 means without prior written permission of the publisher. WALKING WATERBIRDS unmistakable, elegant wader; no similar species in Chile SHOREBIRDS For ID purposes there are 3 basic types of shorebirds: 6 ‘unmistakable’ species (avocet, stilt, oystercatchers, sheathbill; pp. 89–91); 13 plovers (mainly visual feeders with stop- start feeding actions; pp. 92–98); and 22 sandpipers (mainly tactile feeders, probing and pick- ing as they walk along; pp. 99–109). Most favor open habitats, typically near water. Different species readily associate together, which can help with ID—compare size, shape, and behavior of an unfamiliar species with other species you know (see below); voice can also be useful. 2 1 5 3 3 3 4 4 7 6 6 Andean Avocet Recurvirostra andina 45–48cm N Andes. Fairly common s. to Atacama (3700–4600m); rarely wanders to coast. Shallow saline lakes, At first glance, these shorebirds might seem impossible to ID, but it helps when different species as- adjacent bogs. Feeds by wading, sweeping its bill side to side in shallow water. Calls: ringing, slightly sociate together. The unmistakable White-backed Stilt left of center (1) is one reference point, and nasal wiek wiek…, and wehk. Ages/sexes similar, but female bill more strongly recurved. the large brown sandpiper with a decurved bill at far left is a Hudsonian Whimbrel (2), another reference for size. Thus, the 4 stocky, short-billed, standing shorebirds = Black-bellied Plovers (3). -

Life History of the Broad-Billed Motmot, with Notes on the Rufous Motmot

LIFE HISTORY OF THE BROAD-BILLED MOTMOT, WITH NOTES ON THE RUFOUS MOTMOT ALEXAWDERF. SKUTCH N earlier papers (1945, 1947, 1964) 1 gave accounts of the habits of three I species of motmots that inhabit more or less open country, or cool woodland on high mountains. The present paper deals with two species of the wet lowland forest. The nests of these two motmots that we chiefly studied were in sight of each other on the “La Selva” nature preserve, which lies along the left bank of the Rio Puerto Viejo just above its confluence with the Rio Sarapiqui, a tributary of the Rio San Juan in the Caribbean lowlands of northern Costa Rica. They were watched during two visits to this locality, from April to June in 1967 and from March to early June in the following year. The heavy forest of this very rainy region, with its tall, epiphyte-burdened trees, its undergrowth dominated by low palms, and its exceptionally rich avifauna, has been well described by Slud (1960). BROAD-BILLEDMOTMOT (Electron platyrhynchum) One of the smaller members of its family, the Broad-billed Motmot is about 12 inches long. The foreparts of its short body, including the head, neck, and chest, are mainly cinnamon-rufous, with a large black patch on either side, covering the cheeks and auricular region, another black patch in the center of the foreneck, and greenish blue on the chin and upper throat. The posterior parts of the body, including the back and rump, breast and abdomen, are green, more olivaceous above, more bluish below. -

Ultimate Bolivia Tour Report 2019

Titicaca Flightless Grebe. Swimming in what exactly? Not the reed-fringed azure lake, that’s for sure (Eustace Barnes) BOLIVIA 8 – 29 SEPTEMBER / 4 OCTOBER 2019 LEADER: EUSTACE BARNES Bolivia, indeed, THE land of parrots as no other, but Cotingas as well and an astonishing variety of those much-loved subfusc and generally elusive denizens of complex uneven surfaces. Over 700 on this tour now! 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com Blue-throated Macaws hoping we would clear off and leave them alone (Eustace Barnes) Hopefully, now we hear of colourful endemic macaws, raucous prolific birdlife and innumerable elusive endemic denizens of verdant bromeliad festooned cloud-forests, vast expanses of rainforest, endless marshlands and Chaco woodlands, each ringing to the chorus of a diverse endemic avifauna instead of bleak, freezing landscapes occupied by impoverished unhappy peasants. 2 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Bolivia 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com That is the flowery prose, but Bolivia IS that great destination. The tour is no longer a series of endless dusty journeys punctuated with miserable truck-stop hotels where you are presented with greasy deep-fried chicken and a sticky pile of glutinous rice every day. The roads are generally good, the hotels are either good or at least characterful (in a good way) and the food rather better than you might find in the UK. The latter perhaps not saying very much. Palkachupe Cotinga in the early morning light brooding young near Apolo (Eustace Barnes). That said, Bolivia has work to do too, as its association with that hapless loser, Che Guevara, corruption, dust and drug smuggling still leaves the country struggling to sell itself. -

29Th 2019-Uganda

AVIAN SAFARIS 23 DAY UGANDA BIRDING AND NATURE TOUR ITINERARY Date: July 7 July 29, 2019 Tour Leader: Crammy Wanyama Trip Report and all photos by Crammy Wanyama Black-headed Gonolek a member of the Bush-shrikes family Day 1 – July 7, 2019: Beginning of the tour This tour had uneven arrivals. Two members arrived two days earlier and the six that came in on the night before July 7th, stayed longer; therefore, we had a pre and post- tour to Mabira Forest. For today, we all teamed up and had lunch at our accommodation for the next two nights. This facility has some of the most beautiful gardens around Entebbe; we decided to spend the rest of the afternoon here watching all the birds you would not expect to find around a city garden. Some fascinating ones like the Black-headed Gonolek nested in the garden, White-browed Robin-Chat too did. The trees that surrounded us offered excellent patching spots for the African Hobby. Here we had a Falco patching out in the open for over forty minutes! Superb looks at a Red-chested and Scarlet-chested Sunbirds. The gardens' birdbath attracted African Thrush that reminded the American birders of their American Robin, Yellow- throated Greenbul. Still looking in the trees, we were able to see African Grey Woodpeckers, both Meyer's and Grey Parrot, a pair of Red-headed Lovebirds. While walking around the facility, we got good looks at a flying Shikra and spent ample time with Ross's Turaco that flew back and forth. We had a very lovely Yellow-fronted Tinkerbird on the power lines, Green-backed Camaroptera, a very well sunlit Avian Safaris: Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.aviansafaris.com AVIAN SAFARIS Spectacled Weaver, was added on the Village and Baglafecht Weavers that we had seen earlier and many more. -

Bolivia: the Andes and Chaco Lowlands

BOLIVIA: THE ANDES AND CHACO LOWLANDS TRIP REPORT OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2017 By Eduardo Ormaeche Blue-throated Macaw www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | T R I P R E P O R T Bolivia, October/November 2017 Bolivia is probably one of the most exciting countries of South America, although one of the less-visited countries by birders due to the remoteness of some birding sites. But with a good birding itinerary and adequate ground logistics it is easy to enjoy the birding and admire the outstanding scenery of this wild country. During our 19-day itinerary we managed to record a list of 505 species, including most of the country and regional endemics expected for this tour. With a list of 22 species of parrots, this is one of the best countries in South America for Psittacidae with species like Blue-throated Macaw and Red-fronted Macaw, both Bolivian endemics. Other interesting species included the flightless Titicaca Grebe, Bolivian Blackbird, Bolivian Earthcreeper, Unicolored Thrush, Red-legged Seriema, Red-faced Guan, Dot-fronted Woodpecker, Olive-crowned Crescentchest, Black-hooded Sunbeam, Giant Hummingbird, White-eared Solitaire, Striated Antthrush, Toco Toucan, Greater Rhea, Brown Tinamou, and Cochabamba Mountain Finch, to name just a few. We started our birding holiday as soon as we arrived at the Viru Viru International Airport in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, birding the grassland habitats around the terminal. Despite the time of the day the airport grasslands provided us with an excellent introduction to Bolivian birds, including Red-winged Tinamou, White-bellied Nothura, Campo Flicker, Chopi Blackbird, Chotoy Spinetail, White Woodpecker, and even Greater Rhea, all during our first afternoon. -

University Babeù-Bolyai) from Cluj-Napoca (Romania

Muzeul Olteniei Craiova. Oltenia. Studii i comunicri. tiinele Naturii, Tom. XXV/2009 ISSN 1454-6914 THE EXOTIC BIRDS’ COLLECTION OF THE ZOOLOGICAL MUSEUM (UNIVERSITY BABE-BOLYAI) FROM CLUJ-NAPOCA (ROMANIA) ANGELA PETRESCU, DELIA CEUCA Abstract. We present the bird collection catalogue of the world fauna from the patrimony of the Zoological Museum of Cluj (founded in 1859). The studied collection includes 221 specimens belonging to 172 species, 59 families, 18 orders. Especially, we mention a small hummingbird collection made of 45 specimens, 38 species; some endemic species, three from Brazil (Malacoptila striata, Hemithraupis ruficapilla, Paroaria dominicana) and Apteryx oweni (New Zealand). Also, the collection includes other distinguished species as: Goura victoriae, Argusianus argus grayi, Tragopan melanocephalus, Lophophorus impejanus. Keywords: catalogue, collection, exotic bird, museum, Cluj (Romania). Rezumat. Colecia de psri exotice a Muzeului Zoologic (Universitatea Babe-Bolyai) din Cluj (România). Prezentm catalogul coleciei de psri din fauna mondial din patrimoniul Muzeului de Zoologie din Cluj (infiinat în 1859). Colecia studiat; cuprinde 221 de exemplare încadrate în 172 de specii, 59 de familii, 18 ordine. Remarcm în mod deosebit o mic colecie de colibri alctuit din 45 de exemplare, 38 de specii; câteva endemite, trei din Brazilia (Malacoptila striata, Hemithraupis ruficapilla, Paroaria dominicana) i Apteryx oweni (Noua Zeeland). Colecia conine i alte specii deosebite ca: Goura victoriae, Argusianus argus grayi, Tragopan melanocephalus, Lophophorus impejanus. Cuvinte cheie: catalog, colecie, psari, fauna mondial, muzeu, Cluj (România). INTRODUCTION The Zoological Museum of Cluj belongs to the ,,Babe-Bolyai’’ University and it was founded in 1860; it was only one part of the Museum of Transylvanian Society. -

Genomics and Population History of Black-Headed Bulbul (Brachypodius Atriceps) Color Morphs

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School March 2020 Genomics and Population History of Black-headed Bulbul (Brachypodius atriceps) Color Morphs Subir B. Shakya Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Shakya, Subir B., "Genomics and Population History of Black-headed Bulbul (Brachypodius atriceps) Color Morphs" (2020). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 5187. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/5187 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. GENOMICS AND POPULATION HISTORY OF BLACK- HEADED BULBUL (BRACHYPODIUS ATRICEPS) COLOR MORPHS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Biological Sciences by Subir B. Shakya B.Sc., Southern Arkansas University, 2014 May 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A dissertation represents not only the effort of a single candidate but a document highlighting the roles and endeavors of many people and institutions. To this end, I have a lot of people and institutions to thank, without whom this dissertation would never have been completed. First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Frederick H. Sheldon, who has guided me through the six years of my Ph.D. studies. -

Moluccas 15 July to 14 August 2013 Henk Hendriks

Moluccas 15 July to 14 August 2013 Henk Hendriks INTRODUCTION It was my 7th trip to Indonesia. This time I decided to bird the remote eastern half of this country from 15 July to 14 August 2013. Actually it is not really a trip to the Moluccas only as Tanimbar is part of the Lesser Sunda subregion, while Ambon, Buru, Seram, Kai and Boano are part of the southern group of the Moluccan subregion. The itinerary I made would give us ample time to find most of the endemics/specialties of the islands of Ambon, Buru, Seram, Tanimbar, Kai islands and as an extension Boano. The first 3 weeks I was accompanied by my brother Frans, Jan Hein van Steenis and Wiel Poelmans. During these 3 weeks we birded Ambon, Buru, Seram and Tanimbar. We decided to use the services of Ceisar to organise these 3 weeks for us. Ceisar is living on Ambon and is the ground agent of several bird tour companies. After some negotiations we settled on the price and for this Ceisar and his staff organised the whole trip. This included all transportation (Car, ferry and flights), accommodation, food and assistance during the trip. On Seram and Ambon we were also accompanied by Vinno. You have to understand that both Ceisar and Vinno are not really bird guides. They know the sites and from there on you have to find the species yourselves. After these 3 weeks, Wiel Poelmans and I continued for another 9 days, independently, to the Kai islands, Ambon again and we made the trip to Boano.