A Study of Three Columbus Public Parks and Their Usage in Winter Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for Gradua

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C O R P S G Ra N Ts P E R M I T P N C B a N K a R T S C E N T E R Le

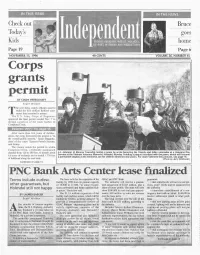

IN THIS ISSUE IN THE NEW S C h e c k o u t B r u c e T o d a y ’s g o e s K i d s SERVING ABERDEEN, HAZLET, HOLMDEL, 1 l o m e KEYPORT, MATAWAN AND MIDDLETOWN Page 19 Page 6 NOVEMBER 13, 1996 40 CENTS VOLUME 26, NUMBER 45 C o r p s g r a n t s p e r m i t _______BY CINDY HERRSCHAFT Staff Writer T he next thing county officials need to build lhe $16 million Belford com muter ferry terminal is money. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers approved the final permit needed Nov. 7 to dredge a portion of the inner harbor of Comptons Creek. R elated story on page 15. After more than two years of deliber ations, the corps determined the project is “in the overall public interest,” James Haggerty, chief of the corps’ Eastern Permit Section, said Friday. The county needs the permit to widen Comptons Creek, a federally maintained channel from 120 to 200 feet, to disturb about J.J. Johnson of Monroe Township recites a poem he wrote honoring his friends and fallen comrades at a Veterans Day Service at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Holmdel, Monday. Holding a plaque inscribed with the poem, which will become 6.6 acres of wetlands and to install 1,720 feet a permanent display at the memorial, are his children Shannon and Jason. For more Veterans Day pictures, see page 18. of bulkhead along the east bank. (Photo by Jerry Wolkowitz) Continued on page 14 PN C Bank Arts Center lease finalized Terms include curfew, The lease calls for the expansion of the GSAC and PNC Bank. -

President Headline

FREE PAINTING THE a newspaper for the rest of us www.lansingcitypulse.com August 27-Sept. 2, 2014 OLDSMOBILE Lansing Art Gallery’s ‘backbone,’ Cathy Babcock, retires after 17 years | p. 11 HEADLINE 2 THE DAILY SHOW Jack Ebling expands Lansing sports coverage with weekday talk show | p. 12 BACk to school PRESIDENT KNIGHT TAKES LCC FROM GRIT TO GLAM - page 8 VIRG BERNERO Why was he passing out negative campaign literature in Okemos on Election Day? | p. 7 Back to school 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • August 27, 2014 City Pulse • August 27, 2014 www.lansingcitypulse.com 3 4 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • August 27, 2014 VOL. 14 Pulse Live ISSUE 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com From director to doctor, Old Town says And now she’s headed for a lot more (517) 371-5600 • Fax: (517) 999-6061 • 1905 E. Michigan Ave. • Lansing, MI 48912 • www.lansingcitypulse.com goodbye to Louise Gradwohl learning as she pursues a career in medicine ADVERTISING INQUIRIES: (517) 999-6705 Gradwohl resigned as director of OTCA PAGE CLASSIFIED AD INQUIRIES: (517) 999-5066 The key is to keep learning. in order to go to Michigan State University or email [email protected] That’s what Louise Gradwohl says is the this fall for pre-med courses and then she’d 5 predominant mindset that has led her in life EDITOR AND PUBLISHER • Berl Schwartz like to go to medical school. [email protected] • (517) 999-5061 so far from ballet dancer to communications She is approaching this change much like ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER • Mickey Hirten intern to director of Lansing’s most vibrant when she started in Old Town, which she Lansing’s bike share pilot program a test of will and patience [email protected] • (517) 999-5064 and growing neighborhoods, the Old Town described as a “big leap of faith.” EDITOR • Belinda Thurston Commercial Association. -

GERMAN VILLAGE SOCIETY BOARD of TRUSTEES MINUTES of the MEETING of June 11, 2019 Present: John Barr, Brittany Gibson, Jim Penika

GERMAN VILLAGE SOCIETY BOARD OF TRUSTEES MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF June 11, 2019 Present: John Barr, Brittany Gibson, Jim Penikas, Kurt MiLLer, Joshua Zimmerman, Marie Logothetis, Terri DaLenta, Robin Strohm, Susan SutherLand, Eric Vanderson Staff and guests: Nancy Kotting, GVS Historic Preservation Advocate; DeLiLah Lopez, German ViLLage Society executive director. The meeting was calLed to order at 6:01 p.m. by President Joshua Zimmerman. Public Participation President Joshua Zimmerman weLcomed Nancy Kotting to the meeting and explained that he’s asked her to attend the beginning of each board meetings to share both high-leveL as weLL as pressing historic preservation updates directLy with the board. Nancy shared some reflections she had in taLking to a resident recently: as one of the oldest designated districts in the country, German ViLLage was recognized when the historic-preservation movement was otherwise honor- ing districts and structures that were for the most part considered elite and over the top. Our neighborhood was an example of the buiLt environment of a working population being recog- nized; since then, we’ve created one of the most affLuent neighborhoods in CoLumbus. She asked board members to reflect on the irony of that situation: without necessariLy intending to, German ViLLage has gone from a working-class, immigrant-fiLLed space to one that protects, cre- ates and perpetuates affLuence. Nancy said she’LL continue to dig into this evolution and the landscape in which German ViLLage was originalLy recognized. Reports of the Officers In his President’s Report, Joshua shared updates on Haus und Garten Tour, which is always our focus in June. -

2015Suspension 2008Registere

LIST OF SEC REGISTERED CORPORATIONS FY 2008 WHICH FAILED TO SUBMIT FS AND GIS FOR PERIOD 2009 TO 2013 Date SEC Number Company Name Registered 1 CN200808877 "CASTLESPRING ELDERLY & SENIOR CITIZEN ASSOCIATION (CESCA)," INC. 06/11/2008 2 CS200719335 "GO" GENERICS SUPERDRUG INC. 01/30/2008 3 CS200802980 "JUST US" INDUSTRIAL & CONSTRUCTION SERVICES INC. 02/28/2008 4 CN200812088 "KABAGANG" NI DOC LOUIE CHUA INC. 08/05/2008 5 CN200803880 #1-PROBINSYANG MAUNLAD SANDIGAN NG BAYAN (#1-PRO-MASA NG 03/12/2008 6 CN200831927 (CEAG) CARCAR EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE GROUP RESCUE UNIT, INC. 12/10/2008 CN200830435 (D'EXTRA TOURS) DO EXCEL XENOS TEAM RIDERS ASSOCIATION AND TRACK 11/11/2008 7 OVER UNITED ROADS OR SEAS INC. 8 CN200804630 (MAZBDA) MARAGONDONZAPOTE BUS DRIVERS ASSN. INC. 03/28/2008 9 CN200813013 *CASTULE URBAN POOR ASSOCIATION INC. 08/28/2008 10 CS200830445 1 MORE ENTERTAINMENT INC. 11/12/2008 11 CN200811216 1 TULONG AT AGAPAY SA KABATAAN INC. 07/17/2008 12 CN200815933 1004 SHALOM METHODIST CHURCH, INC. 10/10/2008 13 CS200804199 1129 GOLDEN BRIDGE INTL INC. 03/19/2008 14 CS200809641 12-STAR REALTY DEVELOPMENT CORP. 06/24/2008 15 CS200828395 138 YE SEN FA INC. 07/07/2008 16 CN200801915 13TH CLUB OF ANTIPOLO INC. 02/11/2008 17 CS200818390 1415 GROUP, INC. 11/25/2008 18 CN200805092 15 LUCKY STARS OFW ASSOCIATION INC. 04/04/2008 19 CS200807505 153 METALS & MINING CORP. 05/19/2008 20 CS200828236 168 CREDIT CORPORATION 06/05/2008 21 CS200812630 168 MEGASAVE TRADING CORP. 08/14/2008 22 CS200819056 168 TAXI CORP. -

EVENING MENUS German Village Haus Und Garten Pretour Party CELEBRATING 150 YEARS of SCHILLER PARK: POETRY

GERMAN VILLAGE HAUS UND GARTEN PreTour PARTY PRESENTED BY VUTECH | RUFF HER REALTORS POETRY. PARTY. PLACE. EVENING MENUS German Village Haus und Garten PreTour Party CELEBRATING 150 YEARS OF SCHILLER PARK: POETRY. PARTY. PLACE. Saturday, June 24, 2017 THANK YOU TO OUR HAUS UND GARTEN TOUR SPONSORS AND PATRONS: Retirement Business Life Auto Home VUTECH | RUFF Here to protect what’s most HER REALTORS important. PROVIDING ON YOUR SIDE SERVICE FOR 13 YEARS. At German Village Insurance, we’re proud to be part of the fabric of this community, helping you protect what you care about most. We consider it a privilege to serve you. Dan Glasener CLU, ChFC, CFP German Village Insurance (614) 586-1053 [email protected] With Support From: Let’s talk about protecting what’s most clh and associates, llc important to you. Not all Nationwide affiliated companies are mutual companies and not all Nationwide members areGerman insured by a mutual company. Nationwide, NationwideVillage is On Your Side, and the Nationwide InsuranceN and Eagle are service marks of Nationwide Mutual Insurance Company. © 2015 Nationwide Mutual Insurance Company. NPR-0784AO (11/15) Juanita & Alex Furuta Alarm One Security Pam & Hank Holste American Family Insurance – The Boldman Agency Nancy Little Athletic Club of Columbus Carolyn McCall & David Renner Beth & Jim Atkinson – Columbus Capital Tim Morbitzer & Giancarlo Miranda Robin & John Barr Carol & Bob Mullinax Jean & Bill Bay Jim Plunkett John Brownley & Lynn Elliott Lisa & Tom Ridgley CASTO Schmidt’s Sarah Irvin Clark David -

WELCOME to Historic Schiller Park! We Are So Pleased That You Want to Learn More About Our Sculpture Exhibit

WELCOME to historic Schiller Park! We are so pleased that you want to learn more about our sculpture exhibit. It is titled “Suspension: Balancing Art, Nature, and Culture” with works by the Polish artist Jerzy Kedziora. It may be helpful to think for a moment about the art of sculpture in general. Sculptures are three-dimensional objects. They have height, width, and depth. They cast shadows. Sculptures occupy space, just as you occupy space. To see a sculpture in full, you will have to walk around the work, looking at all sides as you move around it. In general, sculptures are created through additive or subtractive processes—materials are somehow built up or somehow removed. Sculptures may also be cast from molds, meaning that multiple examples of the same sculpture may exist. Sculptures can be made from a wide variety of materials, including stone, wood, metal, plastic, textiles, and more. They may or may not be painted. Sculptures may be figurative or abstract, small or large, hand-crafted or industrially-produced. Jerrzy Kedziora’s works are beautiful works of hand-crafted art, but they are also amazing feats of balance! You may want to study the figures to see if you can figure out where he has put the weight to keep them suspended in the positions he designed. Jerzy says he isn’t quite sure how he does it. He said many engineers have offered to calculate a formula for him, but they have never been successful – he just has to feel the piece and play with it on a line suspended in the back yard of his studio to get a feel for the balance. -

Developing Our Community (2009)

Developing Our COMMUNITY2009 THE ARENA DISTRICT HITS A HOME RUN: New leisure-time options draw crowds downtown Downtown prepares for new center city, new courthouse, new condos Growing population of Grove City brings new demand for goods, services Lancaster advances as a focal point for employment A supplement to TABLE OF CONTENTS Banks prequalify borrowers. This annual feature of The Daily Reporter is divided into multiple sectors focusing on the residential, commercial and industrial development of each. We look at the projects Shouldn’t electrical contracting firms completed during 2008 and the planned development for 2009 and beyond. Sector 1 - Columbus be prequalified for your project? DEVELOPING OUR Arena District, Downtown, German Village, King-Lincoln District, Clintonville, COMMUNITY 2009 Brewery District, Short North, University District Sector 2 - Northwestern Franklin County Grandview Heights, Upper Arlington, Hilliard, Worthington, Dublin A supplement to The Daily Reporter The Central Ohio Chapter of the National Electrical Contractors Association (NECA) recommends Sector 3 - Northeastern Franklin County Reynoldsburg, Westerville, Easton, Northland, Bexley, New Albany, Whitehall, Gahanna bidder prequalification to anyone planning new construction or renovation to an industrial facility, Publisher: commercial building, school, hospital or home. Dan L. Shillingburg Sector 4 - Southern Franklin County Grove City, Canal Winchester, Pickerington Prequalifications for an electrical contractor should include references, a listing of completed projects, Editor: Sector 5 - Select Communities of Contiguous Counties financial soundness of the firm, the firm’s safety record and most importantly – training provided to Cindy Ludlow Lancaster, London, Newark, Powell, Delaware, Marysville the electricians and technicians who will be performing the installation. Associate Editor: Chris Bailey We have divided the The Central Ohio Chapter, NECA and Local Union No. -

German Village Society Board of Trustees Minutes of The

GERMAN VILLAGE SOCIETY BOARD OF TRUSTEES MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF May 11, 2015 Present: Tim Bibler, Bill Curlis, Greg Gamier, Brittany Gibson, Joe Kurzer, Jeanne Likins, Jeff McNealey, Susan Sutherland, and David Wible. Staff and Guests: Colleen Boyle, Matt Eshelbrenner, Dan Kline, Gary Seman and Shiloh Todorov. The meeting was called to order at 6:05 p.m. by President Likins. Public Participation As a result of the high-wind and rain storm passing through the area, none of the public participants had arrived. President Likins moved to the Report of the President as the first order of business. Ms. Likins gave the Board a report on the first months of progress on the Strategic Plan including the revised Board agenda format. A lengthy review of that agenda format and the role of the ‘Pillars’ and how they are to report to the Board was discussed. A realignment of assignments of the pillars and a recruitment of additional pillars will continue. With the arrival of Dan Kline, Co-chair (with his wife Marie Logothetis who was not able to be present) of the 2015 Haus und Garten Tour, the discussion was interrupted for an up-date on the 2015 tour plans. Mr. Kline reported that all of the homes and gardens were selected early this year and all of them fit nicely into the Preserving the Past, Celebrating Tomorrow theme of this year’s tour. Trustee Brittany Gibson, noted the early success of the pre-tour ticket sales with only 57 seats in homes and 70 tickets to the Party on the Platz remaining. -

Ellsworth American

mericatt.1 \ Ll X. ) *ii%ru i ELLSWORTH, MAINE, WEDNESDAY AFTERNOON, JANUARY 14, DOT ! 1f aitbfttiBnnrntB. LOCAL AKKAlHfv vice, and he uss unanimously re elected, THE CITY FATHERS rs were all the other < fflrera. After the THE BIO BaAL Talk about Taxes at Ad- LET’S TALK INSURaFceT^^ NEW AUVKKTIhElkEIlTs IhIH WKi K. business was transacted, speeches wen Unpaid made by all present and It was a late hour journed Meeting. Exec notice— Fat Calvin Cogvln*. WORK SOON TO BEGIN ON I'ou’ve Rot that to be when tbe broke The mayor hiui o»rd of aldermen met ELJUH property ought protected against loss by Exec notice— K t Mary .1 '**/,. y. meeting up. tire. We’ve the best Exuc notice— Lewis l» Kcmlck. Next Nokomfs Re- last night at an adjourned meeting to WORTH’S WATER POWER. got surest, safest, very protection that Ailmr n lice—Km John E It ark Tuesday evening talk over the unpaid tax situation. i you cau get—ami ttiat's— Ailmr notice— E-t Jor. p B ILad’ey. beksb lodge will Install officers publicly. Probate notice*-Em Nc.ilc li G<rnon. That the situation is and de- t he iuatallat ion will be danc* serious, Probate notice— K-i Lu« Following MEN AND MACHINERY y Moore Walsh. manda is FXPECTEH « prompt action, very evident,and SOLID Prolrate notice—Eat lfe». y lt..wbtml. ing and supper In tbe banquet ball. All FIRE INSURANCE. Piubaie nonce—Em A Lin r " aish. unless can he HERE ABOUT THE MIDDLE OF Odd Fellows are Invited. -

German Village Society Board of Trustees Minutes of The

GERMAN VILLAGE SOCIETY BOARD OF TRUSTEES MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF March 9, 2015 Present: Tim Bibler, Dennis Brandon, Kelly Clark, Bill Curlis, Heidi Drake, Greg Gamier, Brittany Gibson, Joe Kurzer, and David Wible. Staff and Guests: Gary Seman and Shiloh Todorov. The meeting was called to order at 6:05 p.m. by Vice President Drake. Public Participation Civic Relations Chair Nelson Genshaft reported on the Third Street Project’s engineering study and OHM’s preliminary cost estimates for all of the ‘parts’ of the project. Mr. Genshaft noted that on March 31st a public comment program will be held in the Warner Fest Hall so that everyone in the community can see all of the proposed preservation improvements to include streets, sidewalks, drainage, curbs, overhead utilities, lighting, landscaping and streetscape amenities. The project will be a multi-year, multi-phased endeavor so that it will not be as disruptive to quality-of-life issues in the Village. Mr. Genshaft further reported on other activities of the Civic Relations committee including monitoring the Recreation and Parks and City Streets Departments effort to bring the Jaeger/Deshler entry to the Recreation Center parking area into ADA compliance (requiring the entry to be relocated) and the further allocation of funds remaining in the UIRF grant program for repair of brick streets and curbs in the Village. UIRF funds for $400,000 have been prioritized with work to begin as early as 2015 with an additional $600,000 remaining to be allocated and prioritized. The Board engaged in a lengthy question and answer discussion and thanked Mr. -

2016 Impact Report

DONORS MEMBERSHIP, DONATIONS, IN-KIND (10-1-15 THROUGH 9-30-16) $5,000+ Deborah Neimeth & Kristie Nicolosi Heather & Ryan Bone Aimee Deluca German Village Teeth Juvly Aesthetics Mike & Andrea McLane Heath & Jennifer Rittler Studio 33 Salon & Spa The Book Loft George Barrett Lisa & Charles Ohmer Robert & Amy Borman Paolo & Patricia DeMaria Whitening & Blowout Karla Kaeser Peter & Caroline McNally Debbie Roark Studio 595 Boutique GERMAN VILLAGE SOCIETY The Columbus Foundation James L Nichols Mark & Keriann Ours Patrick & Barbara Bowers Nate DeMars Steve & Maryellen Kahn Bridget McNeil Sue & David.Roark Studio Fovero Nurtur the Salon Jay Panzer & Jennifer Matthew & Kristen Diane Demko Germania Singing & Sport Amy Karnes Caitlin McTigue Cheryl Roberto & David Durr Suckel Darci Congrove & John Society Pribble Oberer’s Flowers Heitmeyer Bowersox Heather Densmore & Dax Kartson Emily Mead Magee Theresa Sugar Mike & Rachel Gersper Copious & Notes Panera Bread /Covelli James & Sarah Penikas Laura Bowman Matthew Sanders Sarah & John Kasey JT & Natalie Means Patricia Roberts Mark Sutter Charles Getzendiner COTA Enterprises Peter J Binning Attorney Donna Bowman Jeffrey Dersch Jeffrey Katz Christine Meer Kristen & Bryan Roberts Denise Suttles Pistacia Vera at Law Christopher Boyd Terri Dickey Heather McNees & Ben Jennifer Robinson Tom Dailey & Sung Jin Pak Gibson Aaron Keck Joseph Meranda Brian Sweet Jim Plunkett Richard & Sharon Pettit Ruth Boyd Mary DiGeronimo Lauren Robinson German Village Guesthouse Dennis Giglio & Michael Donna Keller Joyce Merryman -

Magazine FEBRUARY 2009 for the INDEPENDENT COMMUNITY™

A member publication of Lean, Mean & Green ● p. 10 i to i with Tom Zaucha ● p. 20 magazine FEBRUARY 2009 FOR THE INDEPENDENT COMMUNITY™ The Road Ahead What’s over the Horizon as the Food Industry Gears up to Meet the Challenges and Opportunities of the Future Also Inside! Complete 2009 N.G.A. Convention Buyer’s Guide healthy greens FOR THE INDEPENDENT COMMUNITY FEATURES DEPARTMENTS The Long Road Ahead 6 Food on the Floor 24 Change in political leadership. Change in eco- Don’t miss your opportunity to sample some nomic environment. What does the future of the best fresh and prepared food the inde- hold? Executive Vice President and General pendent community has to offer. Counsel Tom Wenning looks at top issues. Supermarket Synergy Showcase 26 Shining Light on Energy 10 Your directory of all the vendors participating The independent community is taking a lead- in this year’s Supermarket Synergy Showcase, ership role on lighting and other energy con- including complete contact information and servation. company descriptions, begins here. Defi ning Healthcare 14 Creative Choice Awards 40 Healthcare is everywhere these days, with a Learn the art of effective retail advertising and lot of defi nitions that don’t really describe the merchandising, as we examine what works problem, or the solutions. Executive Vice Pres- and doesn’t through the experience of this i magazine for the ident Frank DiPasquale examines the issue. year’s Creative Choice Award fi nalists. independent community A Member Publication of the i to i with Tom Zaucha 20 New Product Showcase 44 National Grocers Association.