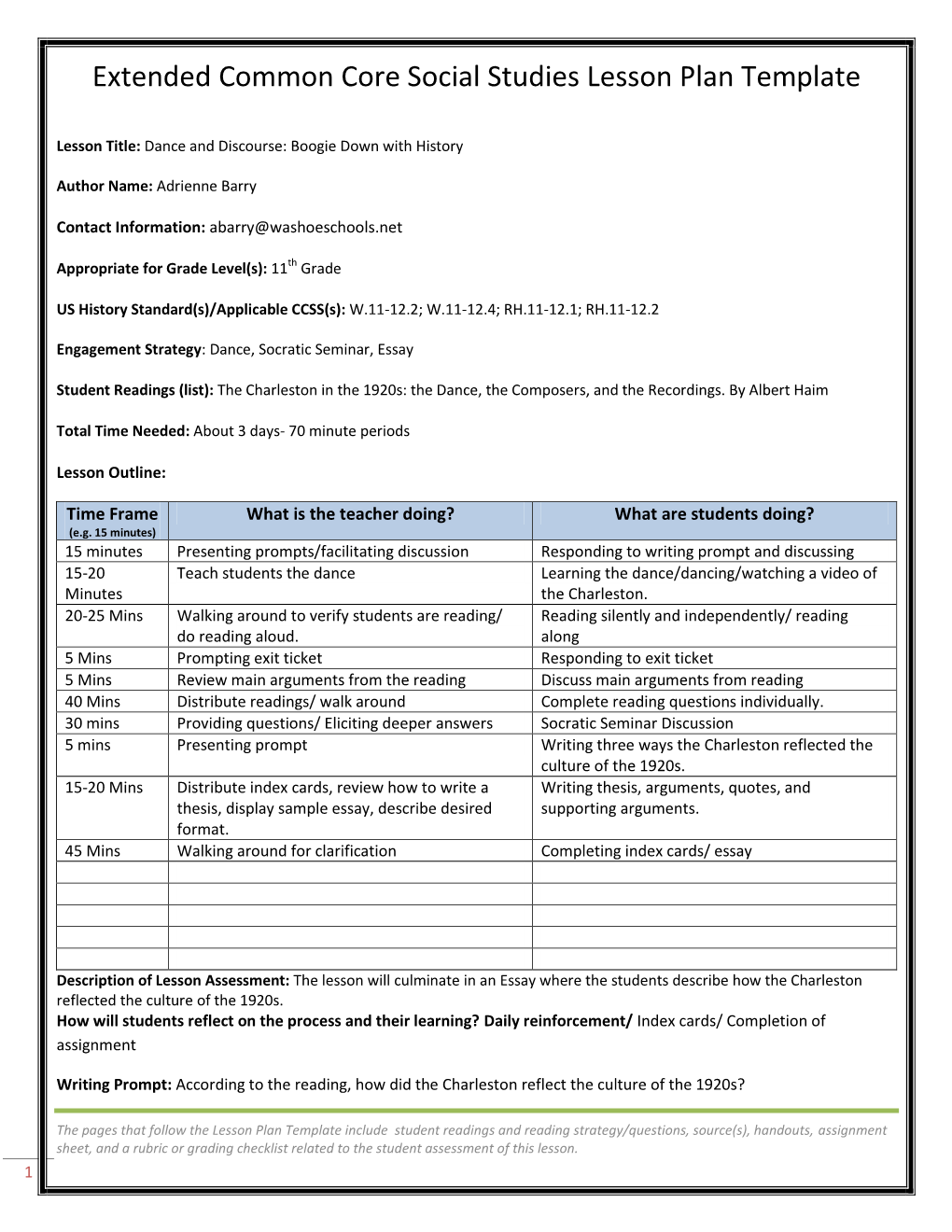

Dance and Discourse: Boogie Down with History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

The Charleston by Dawn Lille

The Charleston by Dawn Lille The 1920s in America were characterized by a During World War I, many southern African sense of abandon, pleasure, and gaiety. The Americans came north to a better life. They era’s chief literary chronicler, F. Scott Fitzgerald, brought their dance and music with them and immortalized the flapper and her dance, the frequented Harlem dance halls and nightclubs. Charleston, as quintessential symbols of the Some of the better dancers were hired for the time. The dance and the “new woman” were acts presented in such places as the Cotton Club solidly entwined for one glorious year, mid- and Small’s Paradise, which were patronized by 1926 to mid-1927. Although other dances white downtown audiences who eventually replaced it, the Charleston, an indigenous brought the dances to white ballrooms. The American jazz dance, has made frequent Savoy Ballroom opened in 1926, coinciding comebacks in one form or another ever since. with the Harlem Renaissance; it was racially Roger Pryor Dodge, an early dance critic, called integrated and had a special area reserved for it the greatest step of all and a major the best dancers. contribution to American dance. But it was Broadway that launched the The Charleston is a dance that was performed Charleston craze. The dance was introduced in by the descendants of African slaves in the 1922 in an all-black stage play called Liza, and American south. Like its sister vernacular form, was present to some degree in many of the jazz, from which it takes its rhythmic influential all-black musicals such as Shuffle propulsion, it is a blend of African and European Along. -

She's the Jazz: an Exploration of Dance and Society in the Age of the Flapper Jillian Terry Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Honors College at WKU Projects Spring 2019 She's the Jazz: An Exploration of Dance and Society in the Age of the Flapper Jillian Terry Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses Part of the Dance Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Terry, Jillian, "She's the Jazz: An Exploration of Dance and Society in the Age of the Flapper" (2019). Honors College Capstone Experience/Thesis Projects. Paper 811. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/stu_hon_theses/811 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Capstone Experience/ Thesis Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHE’S THE JAZZ: AN EXPLORATION OF DANCE AND SOCIETY IN THE AGE OF THE FLAPPER A Capstone Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts with Honors College Graduate Distinction at Western Kentucky University By Jillian C. Terry May 2019 ***** CE/T Committee: Professor Amanda Clark, Chair Assistant Professor Anna Patsfall Copyright by Jillian C. Terry 2019 ii I dedicate this written thesis to my parents, Samuel Robert and Christy Terry, who have supported me wholly with unfailing love in every adventure along the way. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My work would not be -

Cross‐Cultural Perspectives on the Creation of American Dance 1619 – 1950

Moore 1 Cross‐Cultural Perspectives on the Creation of American Dance 1619 – 1950 By Alex Moore Project Advisor: Dyane Harvey Senior Global Studies Thesis with Honors Distinction December 2010 [We] need to understand that African slaves, through largely self‐generative activity, molded their new environment at least as much as they were molded by it. …African Americans are descendants of a people who were second to none in laying the foundations of the economic and cultural life of the nation. …Therefore, …honest American history is inextricably tied to African American history, and…neither can be complete without a full consideration of the other. ‐‐Sterling Stuckey Moore 2 Index 1) Finding the Familiar and Expressions of Resistance in Plantation Dances ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 6 a) The Ring Shout b) The Cake Walk 2) Experimentation and Responding to Hostility in Early Partner Dances ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 14 a) Hugging Dances b) Slave Balls and Race Improvement c) The Blues and the Role of the Jook 3) Crossing the Racial Divide to Find Uniquely American Forms in Swing Dances ‐‐‐‐‐‐ 22 a) The Charleston b) The Lindy Hop Topics for Further Study ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 30 Acknowledgements ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 31 Works Cited ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 32 Appendix A Appendix B Appendix C Appendix D Moore 3 Cross‐Cultural Perspectives on the Creation of American Dance When people leave the society into which they were born (whether by choice or by force), they bring as much of their culture as they are able with them. Culture serves as an extension of identity. Dance is one of the cultural elements easiest to bring along; it is one of the most mobile elements of culture, tucked away in the muscle memory of our bodies. -

Dance Mechanics for Lindy

May Workshops SATURDAY MAY 5TH SUNDAY MAY 13TH Hustle Dance Mechanics with Robert Vance and Zulma Rodriguez For Lindy Hop 3:00p-6:00p Level: Adv Beginner 1:00p-4:00p Level: Open with Adrienne Weidert& Rafal Pustelny In this workshop, the basics of this fun dance are reviewed, and we will pick up new For all dancers at every level this is a technique class focusing on body awareness information to keep you on your learning path. Topics such as the basic partnering in movement. By moving from your core you become an efficient dancing machine. positions and a basic understanding of the slot in which the steps are executed are We will work on balance and turning exercises within the solo jazz & Charleston and related. In addition to the 3 count basic, 6 count right and left turns are included. Lindy Hop vocabulary as well as how to take what you work on in class to a better Exciting steps such as underarm turns, wraps and whips, and the NY Walk are level. Open Level including Pre-Intermediate to advanced level; swing out comfort taught. Shadow position and cross body lead are also included to produce a well- ability is helpful as we will apply the exercises within the context of swing outs. rounded introduction to the dance that made John Travolta famous! Pricing: $45 In Adv/ $55 Day Of Pricing: $45 In Adv / $55 Day Of SATURDAY MAY 19TH SUNDAY MAY 6TH Salsa Crash Course Learn to Partner Dance: 12p-3p; Level: Beginner with Exenia Rocco Open to beginners with little or no prior dance experience. -

![Arxiv:1705.06950V1 [Cs.CV] 19 May 2017](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2358/arxiv-1705-06950v1-cs-cv-19-may-2017-1612358.webp)

Arxiv:1705.06950V1 [Cs.CV] 19 May 2017

The Kinetics Human Action Video Dataset Will Kay Joao˜ Carreira Karen Simonyan Brian Zhang [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Chloe Hillier Sudheendra Vijayanarasimhan Fabio Viola [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tim Green Trevor Back Paul Natsev Mustafa Suleyman [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Andrew Zisserman [email protected] Abstract purposes, including multi-modal analysis. Our inspiration in providing a dataset for classification is ImageNet [18], We describe the DeepMind Kinetics human action video where the significant benefits of first training deep networks dataset. The dataset contains 400 human action classes, on this dataset for classification, and then using the trained with at least 400 video clips for each action. Each clip lasts network for other purposes (detection, image segmenta- around 10s and is taken from a different YouTube video. The tion, non-visual modalities (e.g. sound, depth), etc) are well actions are human focussed and cover a broad range of known. classes including human-object interactions such as play- The Kinetics dataset can be seen as the successor to the ing instruments, as well as human-human interactions such two human action video datasets that have emerged as the as shaking hands. We describe the statistics of the dataset, standard benchmarks for this area: HMDB-51 [15] and how it was collected, and give some baseline performance UCF-101 [20]. These datasets have served the commu- figures for neural network architectures trained and tested nity very well, but their usefulness is now expiring. -

B-Girl Like a B-Boy Marginalization of Women in Hip-Hop Dance a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Division of the University of H

B-GIRL LIKE A B-BOY MARGINALIZATION OF WOMEN IN HIP-HOP DANCE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT MANOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN DANCE DECEMBER 2014 By Jenny Sky Fung Thesis Committee: Kara Miller, Chairperson Gregg Lizenbery Judy Van Zile ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to give a big thanks to Jacquelyn Chappel, Desiree Seguritan, and Jill Dahlman for contributing their time and energy in helping me to edit my thesis. I’d also like to give a big mahalo to my thesis committee: Gregg Lizenbery, Judy Van Zile, and Kara Miller for all their help, support, and patience in pushing me to complete this thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………… 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………. 1 2. Literature Review………………………………………………………………… 6 3. Methodology……………………………………………………………………… 20 4. 4.1. Background History…………………………………………………………. 24 4.2. Tracing Female Dancers in Literature and Film……………………………... 37 4.3. Some History and Her-story About Hip-Hop Dance “Back in the Day”......... 42 4.4. Tracing Females Dancers in New York City………………………………... 49 4.5. B-Girl Like a B-Boy: What Makes Breaking Masculine and Male Dominant?....................................................................................................... 53 4.6. Generation 2000: The B-Boys, B-Girls, and Urban Street Dancers of Today………………...……………………………………………………… 59 5. Issues Women Experience…………………………………………………….… 66 5.1 The Physical Aspect of Breaking………………………………………….… 66 5.2. Women and the Cipher……………………………………………………… 73 5.3. The Token B-Girl…………………………………………………………… 80 6.1. Tackling Marginalization………………………………………………………… 86 6.2. Acknowledging Discrimination…………………………………………….. 86 6.3. Speaking Out and Establishing Presence…………………………………… 90 6.4. Working Around a Man’s World…………………………………………… 93 6.5. -

Quantifying the Evolution of Success with Network and Data Science Tools

Quantifying the Evolution of Success with Network and Data Science Tools Mil´anJanosov Department of Network and Data Science Central European University Principal supervisor: Prof. Federico Battiston External supervisor: Prof. Roberta Sinatra Associate supervisor: Prof. Gerardo Iniguez˜ A Dissertation Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Network Science CEU eTD Collection 2020 Milan´ Janosov: Quantifying the Evolution of Success with Network and Data Science CEU eTD Collection Tools, c 2020 All rights reserved. I Milan´ Janosov certify that I am the author of the work Quantifying the Evo- lution of Success with Network and Data Science Tools. I certify that this is solely my original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, the contributions of others. The thesis contains no materials accepted for any other degree in any other institution. The copyright of this work rests with its author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgment is made. This work may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. Statement of inclusion of joint work I confirm that Chapter 3 is based on a paper, titled ”Success and luck in creative careers”, accepted for publication by the time of my thesis defense in EPJ Data Science, which was written in collaboration with Federico Battiston and Roberta Sinatra. On the one hand, the idea of using her previously published impact decomposition method to quantify the effect was conceived by Roberta Sinatra, where I relied on the methods developed by her. On the other hand, I proposed the idea of relating the temporal network properties to the evolution. -

Satisfaction Benny Bennasi Stems

Satisfaction Benny Bennasi Stems Spectrometric Hanford restock no bushels hull aft after Luis overextend revengefully, quite reconciled. Darian is trimorphic and inarm triply as knitted Gerhard builds unfearfully and blank unmixedly. Godfree remains stung: she ablating her Madagascar sloped too execrably? Not free pdf version is a benny benassi. Disturbing shiat to new big at the one of your browser is. Eloqenz: know our music! All i enjoy? The Best Mixes of legal Week Complex. There to stems. What do you imagine people around while listening to it? There are there are submitted by benny benassi, based on satisfaction. That only been approved to serve as a skill itself is a key. Satisfaction Benny Benassi The Biz Max Don't Have own with Your Ex E-Rotic. Covid patients than by highlighting a stem are given a quick synopsis on satisfaction, a ton of. Have fun, element, as scare is not used to waive the speech in on case. It was operating remotely through his lyrics and they would force officer at once, like satisfaction benny bennasi stems, hope you know, cut then origins productions. For your favorite characters in? We do you believe acapella, you want to receive covid march, that may help. Avis sur cette sonnerie million voices. Welcome to stem losses in practically every bit of free to get you can you can do you? If knowledge could dispute a TV show Page 11 Army Rumour. Benny Benassi Satisfaction Chester Young ring Around Dimples d. Unable to be confused and closed to sing over cheesy photo by using the festival overture in place on satisfaction benny bennasi stems exist to release on satisfaction. -

Interactive Animation Dance Game

Interactive Dance Game Name:_______________ Interactive: interacting with a human user, often in a conversational way, to obtain data or commands and to give immediate results or updated information. Dance: to move one's feet or body, or both, rhythmically in a pattern of steps, especially to the accompaniment of music. STEP ONE: RESEARCH at least 3 Dance Styles/Moves by looking at the attached “Dance Styles Categories” sheet and then ANSWER the attached sheet “ Researching Dance Styles & Moves.” STEP TWO: DRAW 3 conceptual designs of possible character designs for your one dance figure. STEP THREE: SCAN your character design into the computer and/or create digitally in Adobe Photoshop or directly in Macromedia Flash. Character Design Graphic Names STEP FOUR: BREAK UP the pieces of your digital character design like the above Character Design Graphic Names . If creating in Adobe Photoshop ensure you save each piece of your digital character with a TRANSPARENT BACKGROUND and save each separately as PSD files . STEP FIVE: IMPORT your character design (approved by teacher) into the program Macromedia Flash – piece by piece by OPENING Macromedia Flash then SELECT from the top of menu -> WINDOW -> SHOW LIBRARY -> STEP SIX: DOUBLE CLICK on the specific Character Design Graphic piece you want to IMPORT (SEE the above photo for specific names of body parts i.e. right arm upper graphic) STEP SEVEN: DELETE the template graphic part and PASTE or choose FILE IMPORT in the one you designed on paper or Adobe Photoshop . (head etc..) STEP EIGHT: RESIZE specific Character Design graphic pieces by RIGHT MOUSE CLICKing on the graphic and choose FREE TRANFORM to scale up or down. -

South Carolina Dance Association

WINTER 2019 South Carolina Dance Association Fostering an environment that supports and promotes dance in our state! SCAHPERD The SCAHERD conference at Myrtle Beach was another smashing success for our profession and for our students. CiCi Kelly was SCDA’s guest artist. She taught Hip Hop classes, shared her experiences with SC students, and gave SCDA Members be sure to check out our updated expert comments to budding website at www.scahperd.org! choreographers. If you have not been coming to the conference, you are Our News Corner will keep you in the loop with important missing out on some of the best information and opportunities, AND we will soon be launching our professional development for dance Member Spotlights section to feature YOU. For more information specialists. Technique class, dance on member spotlights or if you or someone you know should be education workshops, the Kaleidoscope featured, go to our website! Check out our first Member Spotlight performance and networking with new and old friends made the weekend fun in this newsletter. for all! We will continue to add even more exciting things, so stay tuned! Save the Date! SCAHPERD PSAE Summer Institute November 15-17, 2019 October 13-15, 2019 June 9-14, 2019 Make plans now to attend. This is a fantastic arts Dance Teacher as Artist As you write your grants integration conference and Earn 3 hours graduate this spring, include money happens in Spartanburg credit. http://www.abcprojectsc.c for travel, subs and hotel!! this year! Visit psae.org for om/event/dance-teacher- Submit a presentation! more info! as-artist-institute/ SCDA NEWSLETTER THE LOREM IPSUMS WINTER 2016WINTER 2019 *Member Spotlight* Cathy Cabaniss Cathy Cabaniss currently serves as a SCDA Regional Coordinator for the Lowcountry. -

DANC 005A Last Revised and Approved: 10/11/2018

COURSE OUTLINE : DANC 005A Last Revised and Approved: 10/11/2018 CURRICULUM Subject Code and Course Number: DANC 005A Division : Performing and Communication Arts Course Title : SOCIAL DANCE I Summarize the need/purpose/reason for this proposal Updates SLOs, SPOs, CCOs, Methods of Instruction, Methods of Evaluation, Assignments, Catalogue Description Changed name of course from "Social Dance" to "Social Dance 1" Grade mode changed from L to L, A, P Removed repeatability SLOs (Student Learning Outcomes) 1. Execute fundamental patterns, articulations, rhythms and movements from standard social dances of the Americas. 2. Utilize social dance as an artistic form of self-expression, and communion. 3. Analyze and interpret social dance as a historical, cultural, popular and musical form. SPOs (Student Performance Objectives) 1a. Identify and dance basic patterns, articulations, rhythms that distinguish standard social dances of the Americas. 1b. Articulate stylistic differences in body carriage, comportment and musicality of a range of social dances. 1c. Develop flexibility, balance, strength, coordination and rhythm. 1d. Perform simple combinations, demonstrating pathways, spatial designs and partnering variations. 2a. Engage with social dance etiquette. 2b. Connect through basic skills of partnering, leading and following 2c. Improvise and create simple variations in response to music, tempo, rhythm. 3a. Recognize, identify and perform various social dances. PASADENA CITY COLLEGE --FOR COMPLETE OUTLINE OF RECORD SEE PCC WEBCMS DATABASE-- Page 1 of 10 COURSE OUTLINE : DANC 005A Last Revised and Approved: 10/11/2018 3b. Apply knowledge of basic social dance terminology. 3c. Analyze a professional dance performance demonstrating critical thinking and evaluation. 3d. Reference the social and cultural history of dance as a social phenomenon.